One Hundred Years of the Indy 500

A century ago, the first Indianapolis 500 race started in high excitement and ended in a muddle

The men of the early 20th-century motor press sometimes referred to the 13th circuit of an automobile racecourse as “the hoodoo lap,” not because more bad stuff happened then, but because they fervently wished it would. Coming at that point, a wreck would play nicely into the tabloid trope that superstitions are not to be flouted, and it would give a long car race some much-needed narrative cord. And so it was on May 30, 1911, as several dozen reporters leaned forward anxiously to watch the 40-car field for the first-ever Indianapolis 500-mile race power past the starting line for the 12th time and roar yet again into turn one.

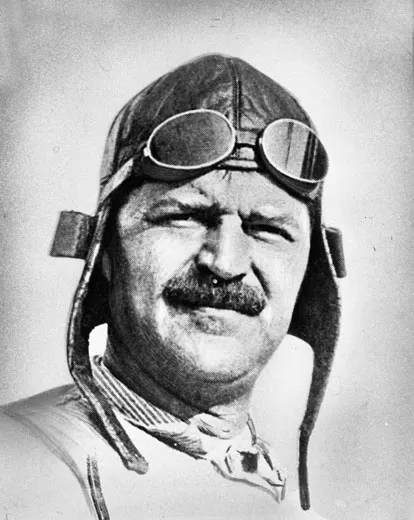

They weren’t a bad lot, the newspapermen who had come to the two-year-old Indianapolis Motor Speedway to cover the event, but they required—and by some standards of judgment deserved—all the help they could get. Many by then had been in Indianapolis for a month or more, pumping up the importance of the Speedway and the coming sweepstakes—the longest race ever contested on the track—via the dispatches they filed for their far-flung dailies. They had recorded the arrival of virtually every “sweepstakes pilot” in the race, especially Ray Harroun, driver of the No. 32 Marmon “Wasp,” an Indianapolis-built car and the only single-seater in the race. (All the other drivers traveled with “riding mechanics,” who manually pumped oil and swiveled their heads constantly to check for oncoming traffic.) They interviewed drop-by celebrities like Detroit Tigers outfielder Ty Cobb and “noted songstress” Alice Lynn, investigated the burgeoning supply of counterfeit $1 general admission tickets, and scrambled for stories about the Indianapolis house cat that “deliberately committed suicide” by jumping from a sixth-story window, the downstate chicken with 14 toes on its left foot and the rumored sightings of a PG-rated pervert known as Jack the Hugger. For men accustomed to doing little more on a workday than walking the length of a boxing ring to ask one toothless man his opinion of another, this was arduous labor.

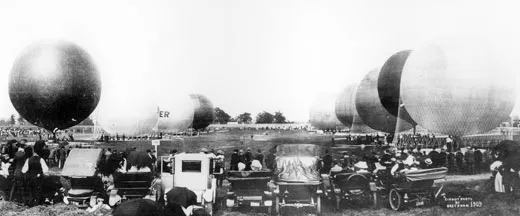

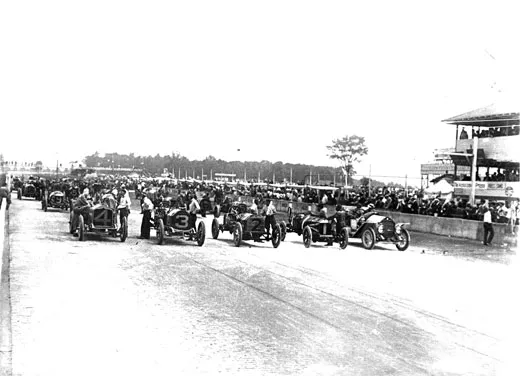

But the 500-mile sweepstakes, when it finally transpired on that surprisingly cool Tuesday morning, wasn’t paying the pressmen back in kind. The race had gotten off to a thrillingly raucous start replete with aerial bombs and a grandstand packed with an estimated 90,000 enthusiasts. People were excited by the amount of money at stake (the winner’s share would be $10,000, an impressive sum in an era when Cobb, baseball’s highest-paid player, made $10,000 a season) and the danger. (In the downtown saloons you could bet on how many drivers, who wore cloth or leather helmets and had no seat belts or roll bars, might be killed.) But with every mile the story line had become more and more scrambled and the spectators more and more subdued. Those charged with describing the “excitement” to an eager audience of millions were feeling the first damp signs of panic. Like every other lengthy automobile contest these experts on baseball and boxing had ever witnessed, this one was damnably confusing. The auto racing tracks of the day simply did not have the technology to keep track of split times and running order once cars began passing one another and going into and out of the pits.

On certain early developments almost everyone could agree. “Happy” Johnny Aitken, in the dark-blue No. 4 National car, had grabbed the early lead, only to be passed, after about seven miles, by Spencer Wishart, a mining magnate’s son driving a squat, gray customized Mercedes said to have cost his daddy $62,000. Eight laps later Wishart (who wore a custom-made shirt and silk tie beneath his overalls) suddenly pitted with a bad tire, leaving the lead to a big brown Knox driven by an unheralded public-school kid from Springfield, Massachusetts, named Fred Belcher. Soon Wishart stormed back onto the course, but into what lap exactly no one, including the judges, could say for certain. The leaders, as mile 30 approached, were starting to lap the stragglers, so the field was a snake eating its own tail. Belcher now found himself running second to a ball of smoke concealing, it was generally believed, the dark red Fiat of 23-year-old David Bruce-Brown, a square-jawed, fair-haired New Yorker from a wealthy merchant family. A class-war theme might be emerging—trust-fund kids versus their working-class counterparts—but then again, perhaps not.

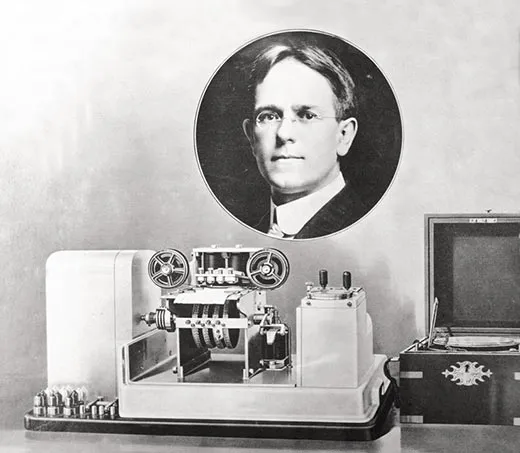

The crowd regained its focus and oohed each time a scoreboard worker indicated a change in running order by manually removing and rehanging the car numbers on their pegs. Still, the denizens of the infield press box—more skeptical than the average fan, and with a better perch—couldn’t help noticing that the Speedway’s four scoreboards were usually not in agreement, and that a crew from the timing department was frantically trying to repair a tripwire that had been snapped by who knows which automobile a lap or two back. (The crew succeeded, but the wire was immediately rebroken.) The Warner Horograph, as the Speedway’s timing system was known, was a ridiculously Rube Goldbergesque device involving miles of wire as well as rolls of paper, typewriter ribbon, springs, hammers, telephones, Dictaphones, marbles and hundreds of human beings. Its sheer complexity was impressive, but the Horograph was utterly useless when it came to recording time and keeping track of races. Given such chaos, was it really so wrong to wish for a spectacular accident that would wipe away the early muddle and allow the beleaguered scribes a second chance at getting a grip on the action?

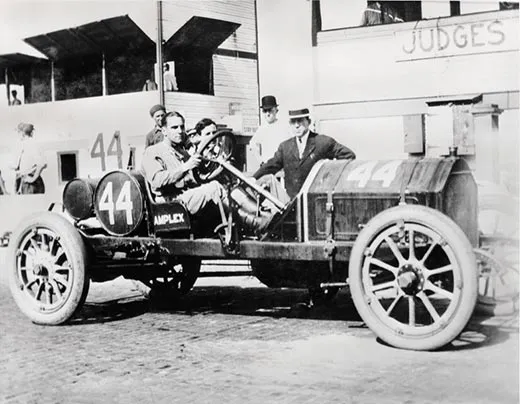

Of course it was wrong, but moral questions wither in the face of a hoodoo, even one conjured by a coven of pasty-faced, ink-stained hacks. Right on cue, the No. 44 Amplex, a bright red car driven by Arthur Greiner and traveling in mid-pack, lost a tire, though accounts vary as to which. The bare wooden wheel hit the bricks hard, causing Greiner’s auto to swerve crazily and veer into the infield, where it plowed through tall meadow grass and began a somersault, only to stop in mid-maneuver, so that it stood straight up, balancing on its steaming grill. The 27-year-old Greiner was flipped from the cockpit like a shucked oyster, with the steering wheel somehow still in his mitts. Riding mechanic Sam Dickson, meanwhile, remained more or less in his bucket seat, one hand planted on the dashboard, the other clutching a leather side-handle, his only restraining device. This was the sort of heart-stopping moment that only auto racing could provide. If the car fell backward, returning to its three remaining tires, he might get nothing worse than a jolt. But if it fell forward, it would drive Dickson’s head into the ground like a tent spike. The crowd fell silent. Dickson tensed. The Amplex rocked on its radiator.

Sensing disaster, scores of spectators began surging over the fence that separated the track apron from the homestretch. This was a common occurrence in the wake of a potentially fatal accident. So eager were some men, women and children to get a closer look that they would risk their own lives by running across a track teeming with racing machines.

In real time, the upended Amplex couldn’t have taken more than a few seconds to fall. And when it did, it fell forward, killing Dickson. As Robert Louis Stevenson once wrote: “There is indeed one element in human destiny that not blindness itself can controvert: whatever else we are intended to do, we are not intended to succeed; failure is the fate allotted.” Dickson’s body was taken with dispatch to the Speedway hospital tent and the race continued without interruption, with the drivers swerving around spectators unable to control their morbid curiosity.

Twenty-five minutes later, the invading spectators had been dispersed by Speedway security guards, and the grandstand resumed its distracted rumble. Standing alone over the wreck of Dickson and Greiner’s race car was a 14- year-old Hoosier named Waldo Wadsworth Gower, who had sneaked into the Speedway the day before and spent the night in the pits. In a letter he wrote in 1959, Gower recalled the piercing sadness brought on by the sight of the mangled auto, reminding him of a similar Amplex he had seen being polished to a high gleam two months before at the American Simplex factory in Mishawaka, Indiana. With “a nice shiny coal oil lantern hung on the radiator cap” and the light “of a bright moon,” he wrote, it had found its way to the city of big dreams.

This is all very touching, I thought, while reading the letter, which had been passed along to me by Sam Dickson’s nephew Scott—but I also couldn’t help wonder why this kid was standing in the middle of the infield getting all Proustian instead of watching the race. Gradually, though, as my research deepened, I came to realize that except in moments of crisis very few spectators were following the action. Newspapers and auto-industry magazines noted that for most of the day many seats in the grandstand, though paid for, went unoccupied, and lines at lavatories and concession stands remained serpentine.

Few watched for the simple reason that no one could tell what he was seeing. The opening half-hour had been bewildering enough, but at least it was fairly apparent in those first 30 miles who held the lead. As the field approached 40 miles, tires started to blow. Belcher’s Knox, Wishart’s Mercedes and several other cars were among the first to hobble into the pits. It took some crews only two minutes to change a tire, others eight or 10 or 15, and no one was timing these stops officially, so the already debatable running order became inscrutable. To compound the chaos, some cars were crossing the finish line and then backing up to their pit, so they (perhaps inadvertently) got credit for a whole additional lap when they emerged and traveled a few feet back across the line. And the worst breaches of order and continuity were yet to come.

What made all this especially maddening was that the race was proceeding exactly as everyone had expected it would, given the natural antagonism between bricks and tires: the smarter drivers, like Harroun, were going at the relatively easy pace of 75 miles an hour or so in an attempt to keep pit stops to a minimum, just as they had said they would in pre-race interviews. You might think that such a conservative and formful contest would help the clocking and scoring officials in their labors. But no. As the trade publication Horseless Age put it, “The system...did not work as expected, merely because the cars were so numerous and tore around so fast.” In other words, if only there hadn’t been a car race at the Speedway that day, the Warner Horograph would have functioned just fine.

A few writers—a largely ignored minority, to be sure—were frank about the problems. “The workers at the great score boards...keep very bad tally on the laps that each car makes,” wrote newspaperman Crittenden Marriott, whose on-deadline dispatch has held up well. “Hundreds of amateur mathematicians do sums upon their cuffs and find that the pace is 70 to 75 miles an hour, a speed that the survivors maintain till the end.” The New York Times: “It was acknowledged that the timing device was out of repair...for an hour during the race.” (Some sources had the downtime as considerably longer.) No one sounded more exasperated than the influential weekly Motor Age, which dismissed the race as “a spectacle rather than a struggle for supremacy between great motor cars.” There were “too many cars on the track. The spectator could not follow the race.”

Most reporters, realizing that a conventional story was easier to compose on deadline than an exposé (and, no doubt, that Speedway publicist C. E. Shuart had been covering their drink tabs), acted as if the race had a coherent storyline. The writers did this partly by guessing at what they were seeing and by agreeing to agree on certain premises. But mostly they accepted the Speedway’s official version of events as disseminated by Shuart—even though it did not always jibe with the venue’s scoreboards, and would change substantially when the judges issued their Revised Results the next day. What any one of these spoon-fed reporters had to say about the running order is mostly worthless. But by braiding their accounts, and occasionally referencing the Revised Results, we can begin to recreate a very rough version of the race.

The dashing David Bruce-Brown, we can say with a fair amount of certainty, played an important role. Virtually all the writers agreed that his Fiat, leading when the Amplex plunged into the infield on lap 13, was still ahead when the field began to stream past the 40-mile mark. At 50 miles, though, accounts diverge. Most dailies said “the millionaire speed maniac” remained on top, but the Horseless Age, in an issue that appeared the day after the race, had Johnny Aitken and his No. 4 National back in front at this point, with Bruce-Brown second and Ralph DePalma third. The Speedway’s Revised Results, meanwhile, put DePalma in the lead at mile 50, followed by Bruce-Brown, then Aitken.

Virtually all sources converge again at mile 60, where they have DePalma ahead, and most also say Bruce-Brown reclaimed the lead soon after and held it for a good long while. At mile 140, some sources place Bruce-Brown a full three laps, or seven and a half miles, ahead of DePalma, with Ralph Mulford and his No. 33 Lozier third. As for Harroun, he had been riding as far back as tenth place for most of the race by some estimates, but he moved into second place at mile 150. Or so said some sources.

The second significant accident of the day occurred at mile...well, here we go again. The Star said it was the 125th mile, the Horseless Age between the 150th and 160th miles when Teddy Tetzlaff, a California driver on Mulford’s Lozier team, blew a tire and crashed into Louis Disbrow’s No. 5 Pope-Hartford, seriously injuring the Lozier riding mechanic, Dave Lewis, and taking both cars out of the competition. The Revised Results have Disbrow dropping out of the race after about 115 miles and Tetzlaff leaving with mechanical problems after a mere 50. So by the Speedway’s lights the participants weren’t racing when their accident occurred and Lewis did not officially fracture his pelvis.

At mile 158, Harroun pitted and turned his car over to a fellow Pennsylvanian named Cyrus Patschke. At about mile 185, Bruce-Brown blew a tire and made his first pit stop of the day, and Patschke took the lead. In the opinion of every reporter at the Speedway, and according to the initial data provided by the Horograph, Patschke reached the 200-mile mark first. The Revised Results, however, have it Bruce-Brown, DePalma, Patschke.

The buffs who still chat about such matters know that May 30, 1911, was not the finest hour for the steering knuckle (the automobile part that allows the front wheels to pivot). Several knuckles had given way early in the day, and at about 205 miles, relief driver Eddie Parker broke the one on the No. 18 Fiat and spun out at the top of the homestretch. Though not a serious mishap—no one was hurt and Parker got out and with a few others pushed his car a few hundred yards into the pits—it set the stage for what steering knuckle historians know as the Big One.

As the leaders, whoever they were, came down the homestretch on what is officially said to be mile 240, Joe Jagersberger’s red and gray No. 8 Case bounced off the concrete retaining wall on the outer part of the track and skidded diagonally toward the infield, traveling perhaps 100 feet. Jagersberger’s riding mechanic, Charles Anderson, fell or perhaps jumped in panic out of the vehicle and wound up underneath it, lying on his back; one of the Case’s rear wheels passed directly over his chest. He was able to get up, however, or at least begin to—when he saw Harry Knight bearing down on him in the battleship gray No. 7 Westcott.

Knight was a rapidly rising young pilot trying to win enough money to marry Jennie Dollie, the so-called Austro-Hungarian dancing sensation. She had at first balked at his pre-race proposals, saying, “No haphazard racer for my life’s companion!” via her hopefully not very expensive interpreter. But she had proffered a tentative yes, the Star reported, after “she found out Knight was a man of good habits and devoted to his mother” and he presented her with a diamond solitaire. All Knight had to do was to pay for the ring, but here now was Anderson literally standing between him and a possible share of the purse. Should he mow down the hapless riding mechanic and perhaps improve his position in the running order—or swerve and quite likely wreck?

His love for Miss Dollie notwithstanding, he crushed the brakes and veered toward pit row—where he crashed into the vermilion and white No. 35 Apperson, taking his own and Herb Lytle’s car out of the race. (Anderson was hospitalized briefly, but survived.) In an article headlined “Who Really Won the First Indy 500?” by Russ Catlin in the Spring 1969 issue of Automobile Quarterly and in a very similar and identically headlined piece by Russell Jaslow in the February 1997 North American Motorsports Journal, the authors state that Jagersberger’s Case hit the judges’ stand, leading the timing officials to scramble for their lives and abandon their duties.

The incident those authors describe is consistent with the sometimes slapsticky nature of the day, yet there is no evidence of a crash into the judges’ area. The official historian of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, Donald Davidson, a revered figure in motor sports and staunch defender of the official results of the race, maintains that Catlin got this wrong, and that Jaslow merely repeated the untruth. Davidson notes that the smashing of the judges’ stand would surely have been mentioned in the newspaper accounts of the race (especially since the structure was just a few yards from the main press box), but that absolutely no reference to a smashup appears in any daily or weekly journal. He is right about that, and what’s more, a brief film clip of this portion of the race, available on YouTube (www.youtube.com/watch?v=DObRkFU6-Rw), appears to bear out Davidson’s contention that there was no contact between the Case and the judges’ structure. Ultimately, though, the question is moot because Jagersberger’s car came close enough to the stand to send timing officials running, and there are contemporary reports stating that after the accidents at mile 240, no one was keeping track of the timing and running order for at least ten minutes. If the operators of the Warner Horograph hadn’t lost the thread of the race narrative before that moment, they would have done so then. In any case, with the halfway point approaching, the Indianapolis News reported, “so much excitement was caused in the judges’ and timers’ stands that the time for the 250 miles was overlooked.” Horseless Age said Harroun’s reliever, Patschke, had the Wasp ahead at the halfway point; the Star said Harroun himself had the car in the lead, and the Revised Results said it was Bruce-Brown, followed by the Wasp, then Mulford’s Lozier.

Taken to a local hospital, the men involved in the incident at mile 240 were found to have serious but not life-threatening injuries. Meanwhile at the Speedway medical tent, one reporter noticed a curious sight: Art Greiner reading an extra edition of the Star that had been dropped off at the Speedway just minutes before. “Bruce-Brown in Lead,” read the main headline on a page-one story that included a report that he had been fatally injured in the accident on lap 13. After being carried to the enclosure, Greiner had likely received the standard Speedway hospital treatment: his wounds packed with black peppercorns to deter infection and bandaged with bed linen donated by local citizens. He had probably been given a few stiff belts of rye whiskey as well; he seemed serene and reflective when the reporter approached.

“I was perfectly conscious when we whirled through the air,” Greiner said. “Dick[son]—poor boy—I guess he never realized what happened.” Then alluding to pre-race complications with the 44, he said, “I’m convinced now that it really does have a hoodoo.”

Around the 250-mile mark, Patschke pulled into the pits and hopped out of the Wasp, and Harroun grabbed a hot-water bottle and hopped back in. If the Wasp truly had the lead, then it was Patschke who had put it there.

All sources had Harroun ahead at 300 miles, but now Mulford was making his move. The Lozier hovered 35 seconds behind the Wasp from mile 300 to 350 and onward, according to Horseless Age. For what it’s worth, the Revised Results have Mulford in front at 350 miles—though the Star spoke for most journalists when it said “Harroun was never headed from the 250th mile to the finish of the race.”

At about 400 miles, the drivers positioned themselves for the final push. DePalma bore down so furiously that he was forced to come in for tires three times over a mere 18 laps. Mulford’s Lozier also had tire trouble: late in the race, he pitted for a replacement that took less than a minute, then came in again a few laps later for several minutes. The crowd, said Motor Age, “realized that it really was a race. They forgot their morbid curiosity in accidents and studied the scoreboards.”

But what exactly did they see there? After 450 miles, the Lozier team would insist that its car was listed first on at least one of the scoreboards and that officials had assured team manager Charles Emise that was one of the rare scoreboard postings people could trust. As a result, Emise would say, he signaled Mulford to ease off in the last 10 or 20 miles so he wouldn’t have to pit and jeopardize his lead. Several members of the Lozier camp would later swear that Mulford saw the green, one-lap-to-go flag first, at which point he was running comfortably ahead of Bruce-Brown, with Harroun third. A mile or so later, Bruce-Brown’s Fiat dropped back behind Harroun.

Mulford, in this version of events, crossed the wire first, and, as was the custom among drivers of that day, ran an “insurance lap” after getting the checkered flag, to be sure that he had covered the required distance. When Mulford went to the winner’s circle to claim his trophy, he found Harroun already there, surrounded by cheering multitudes. Harroun, the official winner, didn’t have much to say beyond, “I’m tired—may I have some water, and perhaps a sandwich, please?” Or something to that effect. Whether he ever wondered if he really crossed the wire first, we will never know. As a driver who came up in the era before windshields were invented, he had learned to keep his mouth shut.

Adapted from Blood and Smoke: A True Tale of Mystery, Mayhem and the Birth of the Indy 500, by Charles Leerhsen. Copyright © 2011 by Charles Leerhsen. Reprinted by permission from Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.

Charles Leerhsen’s previous book was Crazy Good, a portrait of the harness-racing champion horse Dan Patch.