Murder, Marriage and the Pony Express: Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Buffalo Bill

His adventures were sensationalized in print and the Wild West show, but reality was more complicated—and compelling

:focal(541x173:542x174)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/97/a99702a5-3873-4fb4-845d-73b62b82d857/texas_jack_cody_et_al-wr.jpg)

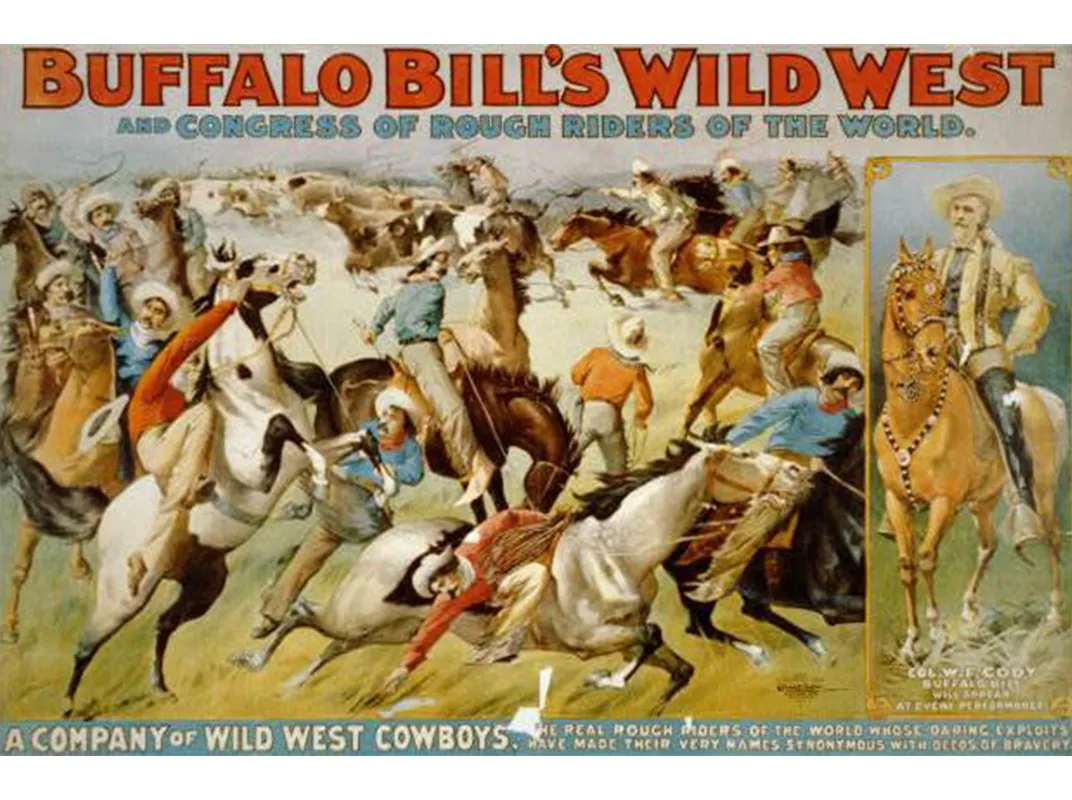

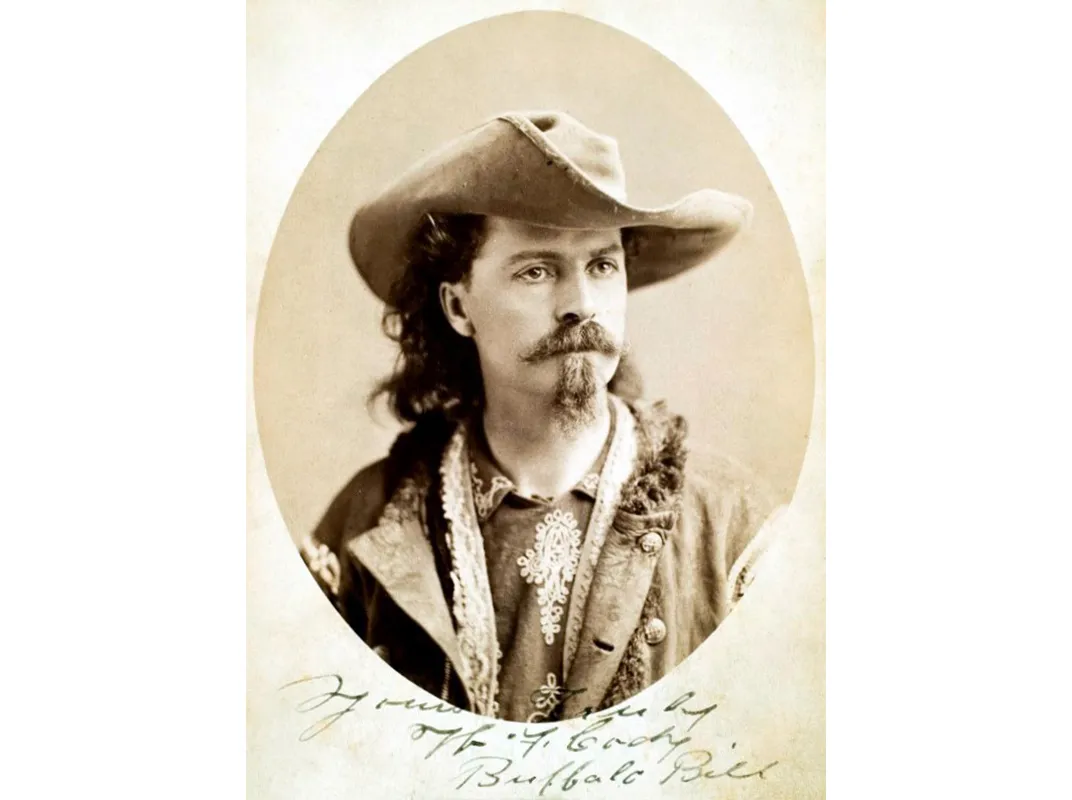

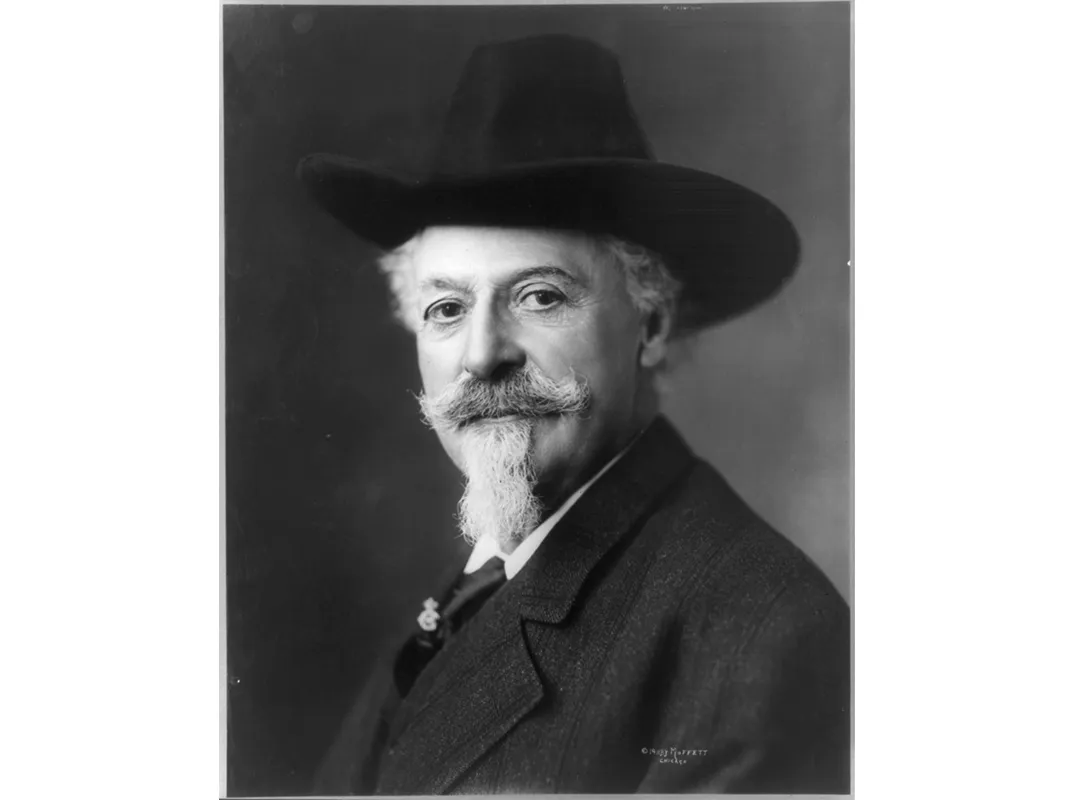

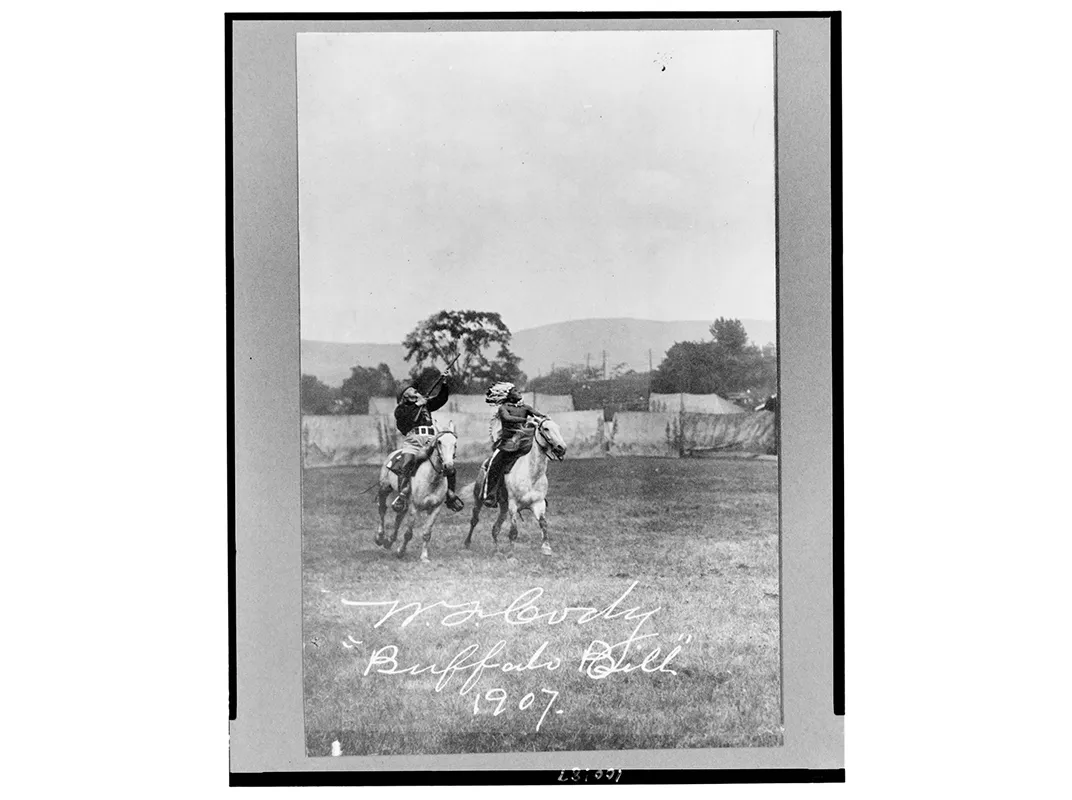

Soldier, cowboy, showman, celebrity—William “Buffalo Bill” Cody wore many hats throughout his long life. In the century since Cody’s death, his Wild West show, which traveled the world for 30 years and featured sharp-shooting, rope tricks, buffalo hunting and reenactments of historical events like Custer’s Last Stand at Little Big Horn, has continued to influence how we view the West and the country’s past.

“This isn’t a simple case of a backwoodsman becoming a celebrity,” says Jeremy Johnston, the Hal and Naoma Tate Endowed Chair and curator of Western history at the Smithsonian-affiliated Buffalo Bill Center of the West. “He was quite in tune with American society, American politics, and was very interested in using technology to tell the story of the American West.”

Johnston grew up 20 miles east of Cody, Wyoming, (a town named for Buffalo Bill, who had a hand in its founding) and his family history in the area stretches back to when Cody was in his heyday. Much as Johnston loved the adventure stories of Buffalo Bill, his real passion has been digging into archival research as the managing editor of the Papers of William F. Cody project.

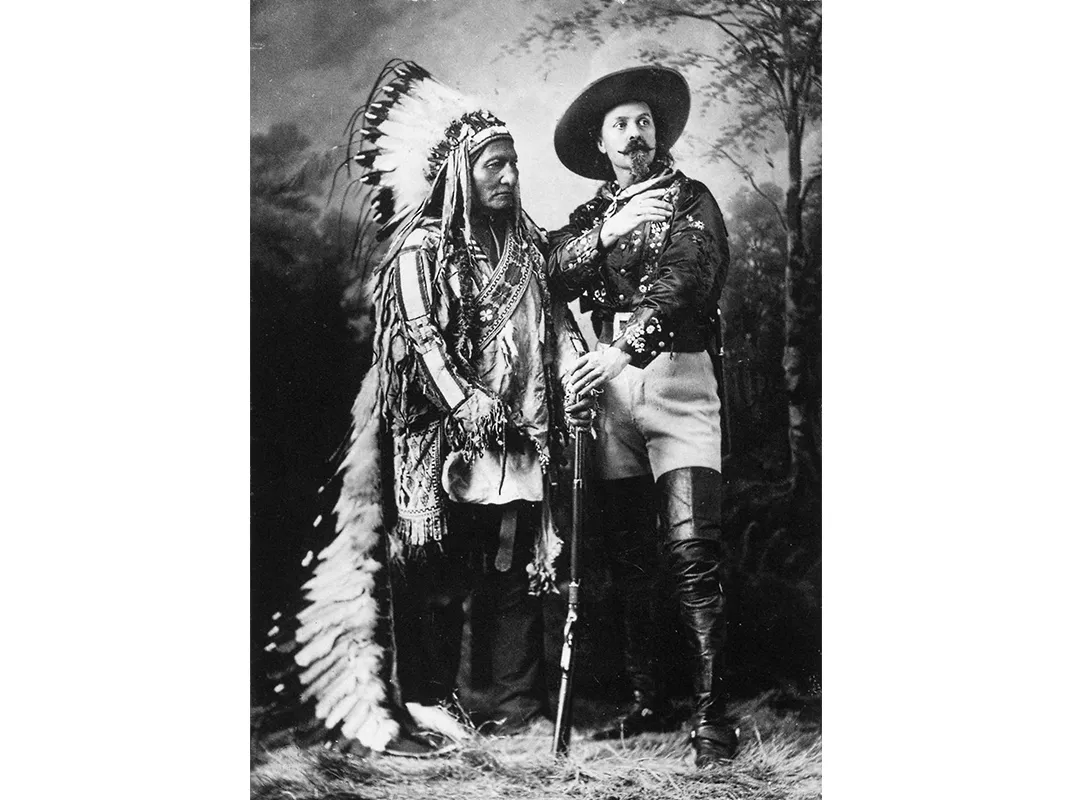

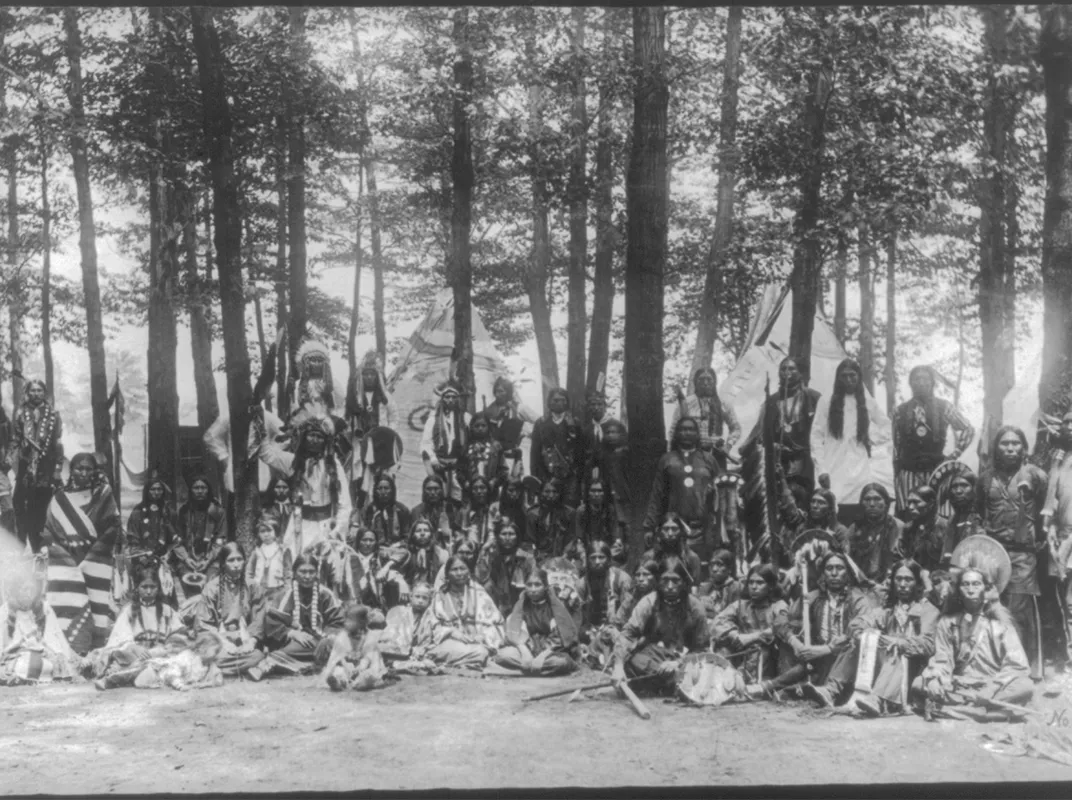

“If you grew up playing cowboys and Indians, you did so because Buffalo Bill’s Wild West made that such a popular part of our memory of the American West,” Johnston says. Cody’s show was populated with Lakota and other Plains Indians tribes, and they were portrayed as aggressors who attacked wagon trains and settlers’ cabins—which didn’t accurately reflect the complex reality.

But even more than that, Cody shaped how the public thinks about history.

“If I was to fault him on anything that still impacts us to this day, it’s the idea that history is entertainment—history as sensationalized authentic depictions in the past,” Johnston says. “Take that model and apply it to many components of U.S. history. World War I, Vietnam—there’s always been a very strong element of entertainment shaping how we view history and our past.”

This makes getting to the truth of Cody’s life all the more difficult; legend and fact tended to blur in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. But for Johnston, it’s all part of the fun.

In celebration of the 100 years that have passed since Buffalo Bill died, check out 10 surprising episodes from his larger-than-life life.

1. He probably wasn’t a rider for the Pony Express

When California entered the United States as a free state in September 1850, one immediate need was to speed up the rate of communication with the rest of the union. With that goal in mind, Russell, Majors and Waddell (the largest transportation company in the West) started the Pony Express in 1860. Comprised of 400 horses and relay stations built 10 to15 miles apart, with larger stations 90 to120 miles apart (for riders to change and rest), the company claimed all mail would be delivered in a record 10 days. But there were plenty of delays in mail delivery, caused by everything from Native American hostilities to the deaths of riders caused by bad weather and dangerous river crossings. But the Pony Express did succeed in carrying word of Abraham Lincoln’s victory in the 1860 presidential election from Fort Kearney, Nebraska, to Placerville, California in only five days.

At age 11, Cody did carry messages on horseback for the freighting firm Major and Russell (which became Russell, Majors and Waddell). But historians have had a hard time verifying his assertions that he worked for the Pony Express. There are contradictions in his autobiography, and one historian even concluded that when Pony Express existed, Cody was in school in Leavenworth, Kansas, and couldn’t have been riding back and forth across Wyoming at the same time.

2. His father was stabbed when he gave an anti-slavery speech

Isaac Cody was a surveyor and real estate investor, born in Ontario, Canada, in 1811 with a childhood in Ohio. He moved around the Midwest his whole life, from Iowa Territory, where William was born, than on to Kansas during a time when the new territory was at its most tumultuous. In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act stated that all U.S. territories possessed self-government in all issues, including slavery, turning Kansas into a literal battleground between free state forces and pro-slavery. The town of Leavenworth, where the Cody family lived, was pro-slavery and the groups regularly held meetings at Rively’s trading post. On Sept 18, 1854, Isaac stumbled into one such gathering and was asked to voice his opinion. When he said he didn’t want slavery extended, he was stabbed twice in the chest with a Bowie knife. Complications from the injury ultimately led to his death in 1857.

3. He hunted buffalo with Russian royalty

When a Russian delegation led by Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, took a four-month goodwill tour of the U.S. in 1871-72, the royal visit was big news—especially when they went on a buffalo hunt. Organized by General Philip Sheridan (best known for his Shenandoah Valley Campaign on behalf of the Union in 1864), the hunt would take place in January at Red Willow Creek in Nebraska. William Cody traveled with them as a scout. The event was widely publicized, with newspapers writing about the Grand Duke’s affection for an “Indian princess,”—a detail that was almost certainly fabricated to spice up the story.

4. His nickname came from a job with the Kansas Pacific Railroad

Before his long run as impresario of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Cody bounced around a number of jobs. In 1867 he became a hunter for the Kansas Pacific branch of the Union Pacific Railroad. For a year and a half, Cody delivered 12 bison a day to the hungry workers. It’s estimated he killed more than 4,000 in one eight-month period, and he once killed 48 buffalo in 30 minutes. Despite supporting conservation measures like implementing a hunting season, Cody’s over-hunting and that of American soldiers contributed to the near-extinction of buffalo.

5. Bill named his gun “Lucretia Borgia” after the famed Italian noblewoman

For shooting buffalo and other targets, Cody employed his Springfield .50 caliber trapdoor needle gun. Cody named the gun for Renaissance Italian femme fatale Lucretia Borgia. Borgia was perhaps best known as the subject of a Victor Hugo play, and had a reputation for being beautiful but deadly. Today Cody’s gun is exhibited at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, but its stock is missing and appears to have broken off at some point. Though no one knows what actually happened, there are rumors that Cody broke it over an elk to kill the animal, or that Grand Duke Alexei of Russia borrowed for the hunt and his horse stepped on it.

6. He performed for Queen Victoria’s Jubilee

Thanks to the work of his manager, Nate Salisbury, Buffalo Bill was invited to perform in London’s American Exhibition in 1887. His voyage across the Atlantic included “83 saloon passengers, 38 steerage passengers, 97 Indians, 180 horses, 18 buffalo, 10 elk, 5 Texan steers, 4 donkeys, and 2 deer.” Before the show opened, the camp was visited by former prime minister William Gladstone and by the Prince of Wales (future King Edward VII) and his family. Annie Oakley even shook hands with the Prince, and he was so charmed—despite the breach in etiquette—that he encouraged his mother, Queen Victoria, to see it. A performance was arranged for May 11. It was the first time since her husband’s death two decades earlier that Queen Victoria appeared in person at a public performance. She liked it so much, she asked for another performance on the eve of her Jubilee Day festivities, with the kings of Belgium, Greece and Denmark, and the future German Kaiser William II in attendance. The twice-a-day performances at the American Exhibition averaged crowds around 30,000.

7. He supported women’s rights and suffrage…

After years spent in the presence of women like Annie Oakley and Calamity Jane, it’s perhaps no surprise that Cody supported women’s rights. But given how polarizing the fight for suffrage could be, Cody’s vocal support still seems revolutionary. In an interview with The Milwaukee Journal from April 16, 1898, a reporter asked Cody if he supported women’s suffrage. “I do,” the famous showman responded. “Set that down in great big black type that Buffalo Bill favors woman suffrage… These fellows who prate about the women taking their places make me laugh… If a woman can do the same work that a man can do and do it just as well, she should have the same pay.”

When the reporter followed up with a question about whether women should have all the same liberties and privileges of men, Cody was unequivocal in his response. “Most assuredly I do…. If they want to meet and discuss financial questions, politics, or any other subjects let ‘em do it and don’t laugh at ‘em for doing it. They discuss things just as sensibly as the men do, I’m sure and I reckon know just as much about the topics of the day.”

8. … As well as civil liberties for Native Americans

“I never scouted with a party of soldiers after Indians that I didn’t feel a bit ashamed for myself and a whole heap sorrier for them,” Cody was overheard saying by a Dallas Morning News reporter in 1901. And while Buffalo Bill’s Wild West portrayed Native Americans as villains by casting them in the role of attackers, his real opinions were more complicated.

“In his writing it’s very clear there was tremendous respect for American Indians,” Johnston says. “He would tell his readers that [Native Americans] had every right to resist what was happening to them, and to fight back.”

9. He had the original tabloid marriage

In some ways, Cody was the original reality television star, long before the medium was invented. Cody married Louisa Frederici in 1866, but spent long stretches of time away from her and their four children. In 1904 he sued for divorce, claiming Louisa had attempted to poison him, and the suit turned into a huge scandal covered by most major papers, with reporters dredging up Cody’s earlier affairs and bouts of drinking. The judge ultimately dismissed the case, since the accusations of poisoning were baseless. The couple stayed married and managed to reconcile before Cody’s death in 1917.

10. He was involved in one of the first federal water development projects

In addition to earning money through show business, Cody also invested in land in Wyoming and was involved in the Shoshone Irrigation project. In 1904, Cody transferred his water rights to the Secretary of the Interior and exploratory drilling began for Shoshone Dam that year (later renamed Buffalo Bill Dam). Today the Shoshone Project (system of tunnels, canals, diversion dams and Buffalo Bill Reservoir) irrigates more than 93,000 acres of beans, alfalfa, oats, barley and sugar beets. The dam was one of the first concrete arch dams built in the U.S. in 1910, and also the tallest in the world at 325 feet.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/97/a99702a5-3873-4fb4-845d-73b62b82d857/texas_jack_cody_et_al-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)