Memoirs of a World War II Buffalo Soldier

In a recently published memoir written over 60 years ago, veteran James Daugherty details his experiences as an African-American in combat

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/James-Pat-Daugherty-Buffalo-Soldier-631.jpg)

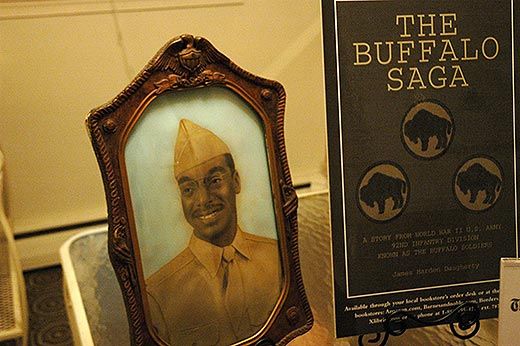

On his dining room table James “Pat” Daugherty had arranged some old faded photographs from his Army days, his Bronze Star, a copy of his recently published World War II memoir, The Buffalo Saga, and his olive-drab steel helmet, marred near the visor by a chunk of now-rusted iron.

“If you feel the inside of the helmet, you can see how close it was,” he says of the shrapnel from a German mortar that struck the young private in Italy in the fall of 1944. A few more millimeters, and he might never have lived to write his memoir, which is what I went to his home in Silver Spring, Maryland, to learn about.

Daugherty, 85, served in the Army’s storied 92nd Infantry Division, which was made up almost entirely of African-Americans and was the last racially segregated unit in the U.S. armed forces. Known as the Buffalo Soldiers—a name that Native Americans had bestowed on a black cavalry unit after the Civil War—men of the 92nd division were among the only African-Americans to see combat in Europe, battling German troops in Italy. In 1948, President Truman issued an executive order that ended racial segregation in the military.

Daugherty, drafted at age 19, was so deeply affected by his two years in the division that he wrote an account of the experience soon after he returned home in 1947. He self-published the story this year, virtually unchanged from the manuscript he had scribbled in longhand. The Buffalo Saga promises to be a significant addition to the history of African-American troops in World War II because it was written by a participant almost immediately following the events in question, rather than recollected or reconstructed years later.

Daugherty says he put pen to paper because friends and family members were always asking, “ ‘What did you do when you were over there?’ ”

Years ago he tried once to find a publisher, with no success. “I think the content was too caustic,” says Dorothy, his wife of 59 years.

The Buffalo Saga is indeed a raw, unvarnished, often angry account of a decorated young soldier’s encounter with institutionalized racial prejudice. Once, while fighting in Italy in 1945, another soldier in the 92nd Infantry Division said his company had lost too many men to continue fighting. Daugherty asked why the officers couldn’t just call up replacements. “Look, bud, they don’t train colored soldiers to fight,” the soldier told Daugherty. “They train them to load ships, and you don’t expect them to put white boys in a Negro outfit, do you? What do you think this is, a democracy or something?”

Daugherty’s memoir also recalls the time a black soldier got shipped out to the front lines in Italy after confronting a white officer. Word was the officer had threatened to send him where he’d get his “smart Negro brains” blown out. “I merely wondered how many men were here to be punished because they had dared to express a desire to be treated like men,” Daugherty writes.

But the book isn’t a screed. It’s an honest, even poignant account of a young man fighting in a war.

One night in late December 1944, Daugherty’s platoon got orders to patrol a mountain and not come back until it had a prisoner. He and the rest of his company ducked under friendly fire, and Daugherty advanced ahead of the troops. “The first thing I knew I had stumbled upon a barrier constructed of wooden plank and heavy-cut branches,” he wrote. “I was about to try to cross this when I caught the movement of a form in the darkness. I looked up, and it was a Jerry.” He and another private captured him and returned to camp. For this, Daugherty earned his Bronze Star.

The Buffalo Soldiers of World War II arouse intense scholarly and popular interest (a recent treatment is Miracle at St. Anna, a 2008 film by director Spike Lee based on the novel by James McBride). Their long-overlooked achievements gained national prominence in 1997, when seven African-American soldiers were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Only Vernon Baker, who served with the 92nd Infantry, was still alive.

“It was something that I felt should have been done a long time ago,” Baker said at the time. “If I was worthy of receiving a Medal of Honor in 1945, I should have received it then.” In 2006, Baker published his own memoir, Lasting Valor, with the help of journalist Ken Olsen.

The medals were issued after a historian documented that no African- American who fought in the war had even been nominated for one. “At the end of World War II, the white officers in particular wanted to wash their hands of the Italian campaign experience with the 92nd Division,” says historian Daniel Gibran, author of The 92nd Infantry Division and the Italian Campaign in World War II. “It was an experience that a lot of white officers didn’t really want, and they might as well soon forget that kind of experience.”

At the end of the war, Daugherty returned to his hometown, Washington, D.C., determined, he wrote at the time, “to help make it a place that shows compassion for, humility for, high regard for, and values all its citizens alike.” Of course, Daugherty and his fellow Buffalo Soldiers returned not to a hero’s welcome but to segregated schools and job discrimination. “The road has been long and hard; blood and sweat, death and destruction have been our companions,” he wrote. “We are home now though our flame flickers low. Will you fan it with the winds of freedom, or will you smother it with the sands of humiliation? Will it be that we fought for the lesser of two evils? Or is there this freedom and happiness for all men?”

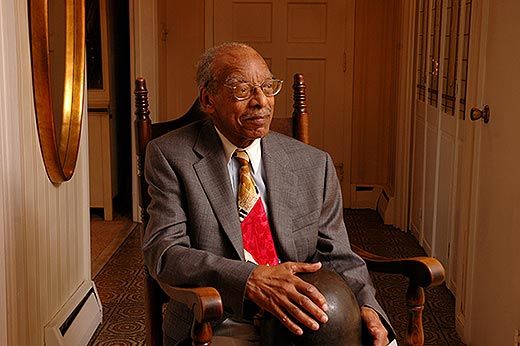

Daugherty didn’t let his own flame go out. He went on to study at Howard University in Washington, D.C. on the G.I. Bill and to work as an administrator in the U.S. Public Health Service. He was the first African-American to serve on the board of the Montgomery County Public Schools, among the nation’s largest public school districts. Following publication of his book, Daugherty has become somewhat of a celebrity in his adopted hometown—July 28 is now officially “Buffalo Soldier James Daugherty Day” in Silver Spring.

He sits in the living room of the ranch-style house he built nearly five decades ago and in which he and his wife raised their four sons. He recalls that his work in the public health system also taught him about inequity.

“The majority of the health centers were in poor, black areas where people couldn’t get health care and all that,” Daugherty says. “But I also had to go up into West Virginia to the coal mines, and they were mistreated something terrible. A lot of these weren’t black, they weren’t Asian; they were white, Caucasian.”

Daugherty’s original handwritten manuscript remains sealed in two yellowed envelopes. Daugherty mailed them to himself more than half a century ago, in lieu of obtaining an official copyright. The postmarks read April 28, 1952. It’s his way of proving that The Buffalo Saga is his story.