The Marquis de Lafayette Sails Again

Now that the ship that the Frenchman took on his 1780 trip to America has been rebuilt, its time to revisit his role in history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/0a/730add49-3e9b-4a00-8052-2fa125ce51c4/apr2015_e12_lafayette.jpg)

The sun was sparkling off the Bay of Biscay and a light breeze barely ruffled the sails as the three-masted frigate l’Hermione headed out from La Rochelle for sea trials one morning last October. It was a beautiful day, dammit! This would be one of the new ship’s first times out in open water, and the captain, a Breton sea dog named Yann Cariou, was eager to see what it and its crew of 18 seasoned sailors and 54 volunteers could do. The balmy weather would test neither.

Cariou fired up the two 400-horsepower Italian engines and motored north looking for wind. At dinner in the galley, he made a show of peeking under the tables, as if he were playing a children’s game. “No wind here,” he says with mock gravity. But there was good news, meaning bad news, on the radar. A big storm off Iceland was generating nasty low-pressure systems as far south as Brittany, so that’s where we headed.

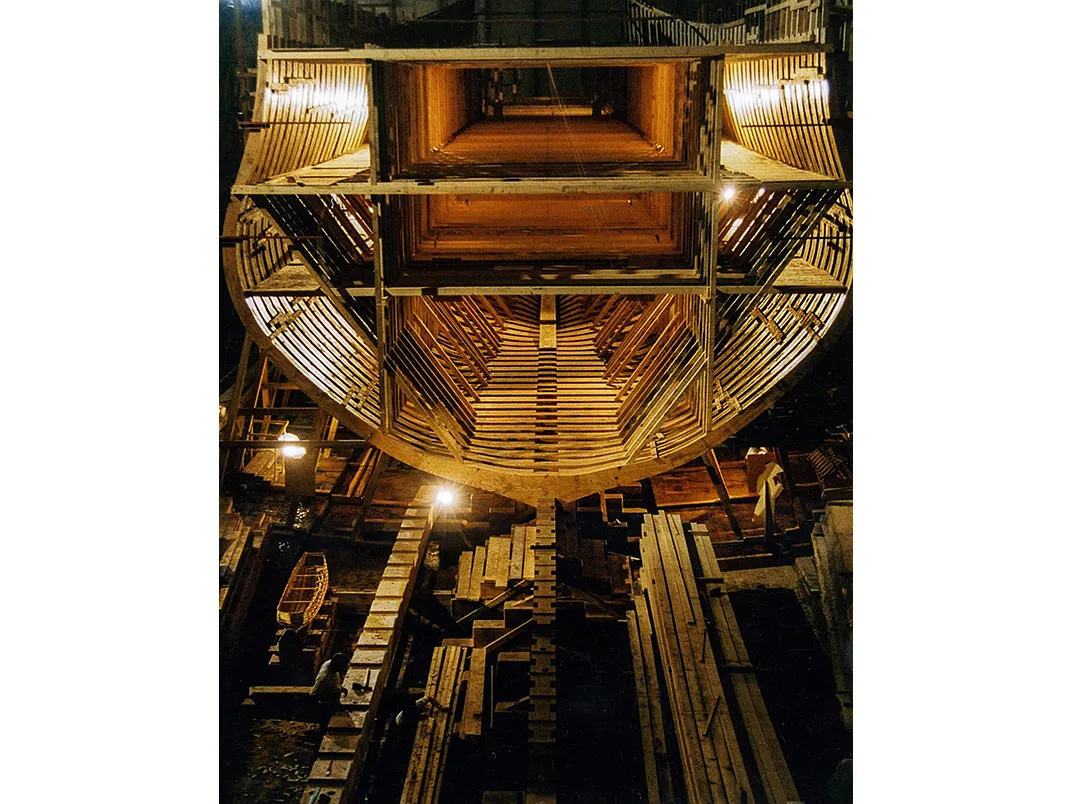

Many people had waited a long time for this moment. The French spent 17 years and $28 million replicating the Hermione down to the last detail, from its gilded-lion figurehead to the fleur-de-lis painted on its stern. When the original Hermione was built in 1779, it was the pride of a newly re-energized French Navy: a 216-foot, 32-gun barracuda that could take a real bite out of the arrogant English, who not only ruled the waves but concocted an in-your-face anthem about it—“Rule, Britannia!”—in 1740.

With a sleek, copper-bottomed hull, the Hermione could out-sail almost any ship it couldn’t out-shoot. Even the English recognized the Hermione’s excellence when they captured its sister ship, the Concorde. They promptly reverse-engineered their prize, drawing detailed schematics to help recreate the vessel for their own fleet.

This proved a stroke of luck 200 years later when France decided it was tired of being the only great seagoing nation without a replicated tall ship of its own. “In the 1980s, we restored the shipyards at Rochefort, where l’Hermione was built, and made them a cultural monument,” says Benedict Donnelly, who heads France’s Hermione project, the Association Hermione-La Fayette, supported by public funds and private donations. “But then in the ’90s we said, we’re missing something. A recreated tall ship. France is really the poor relation among nations in this department. The Hermione was the jewel of the navy from a glorious moment in French maritime history—which hasn’t always been glorious, thanks to our friends the English. Happily, our English friends had captured the Hermione’s sister ship and left us the plans.”

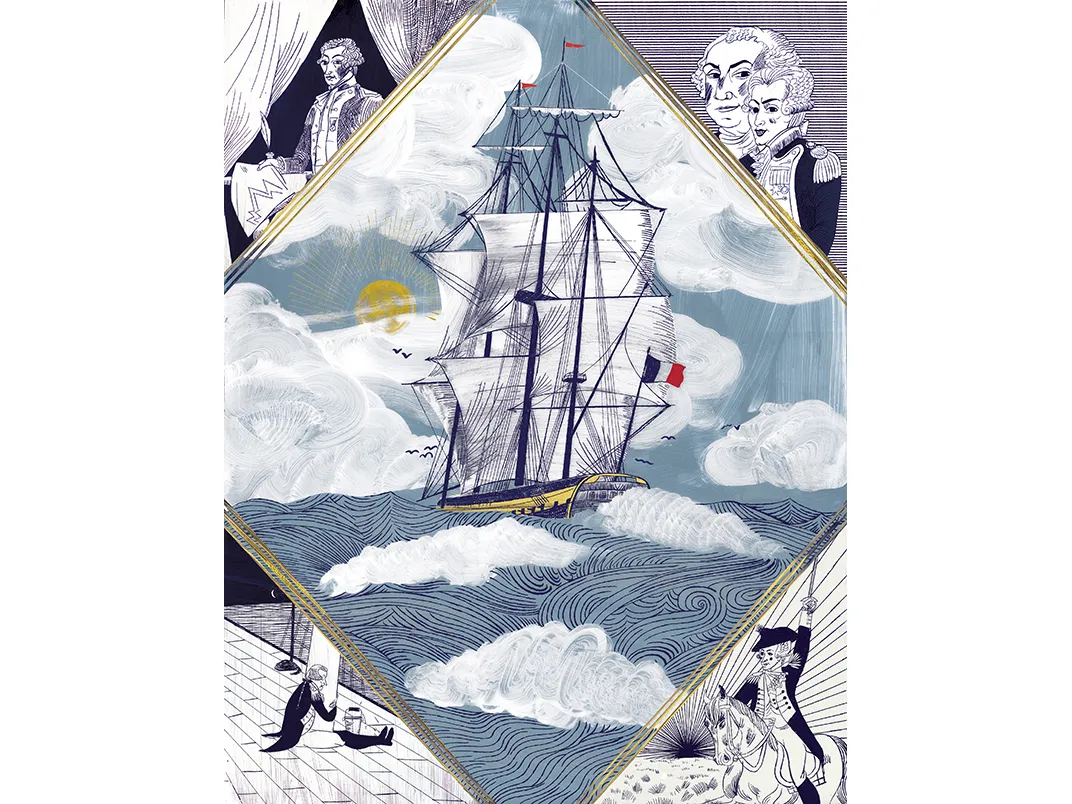

There’s another reason that the Hermione sails again—it possesses a particular transatlantic back story and cachet. In March 1780, the Hermione set out from Rochefort bound for Boston. Its speed and agility suited it ideally to the task of carrying Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, back to America. He was charged with giving George Washington the nation-saving news that France would soon be sending an infusion of arms, ships and men.

That life support was due in no small part to Lafayette’s tireless cheerleading. His earlier efforts had helped nudge King Louis XVI into recognizing the United States and signing a defensive alliance with it in 1778 (just how big a nudge is open to debate, since French policy was already strongly inclined in this direction for reasons of pure realpolitik). Now, Lafayette, the public face of France in the United States, was returning to deliver the goods.

Surely Lafayette’s name could work the same fund-raising magic for a recreated Hermione, this time in the America-to-France direction. The connection with Lafayette has brought in U.S. donors under the auspices of the Friends of Hermione-Lafayette in America, a nonprofit that has helped to raise roughly one-quarter the $4.5 million it is costing to send the replicated Hermione from Rochefort voyaging to America and back. Donnelly, whose own background seems tailor-made for overseeing the Hermione project since 1992—his mother is French and his American father participated in the D-Day invasion at Normandy—says that was never a consideration. “Choosing to rebuild Lafayette’s boat was not a question of marketing,” he insists.

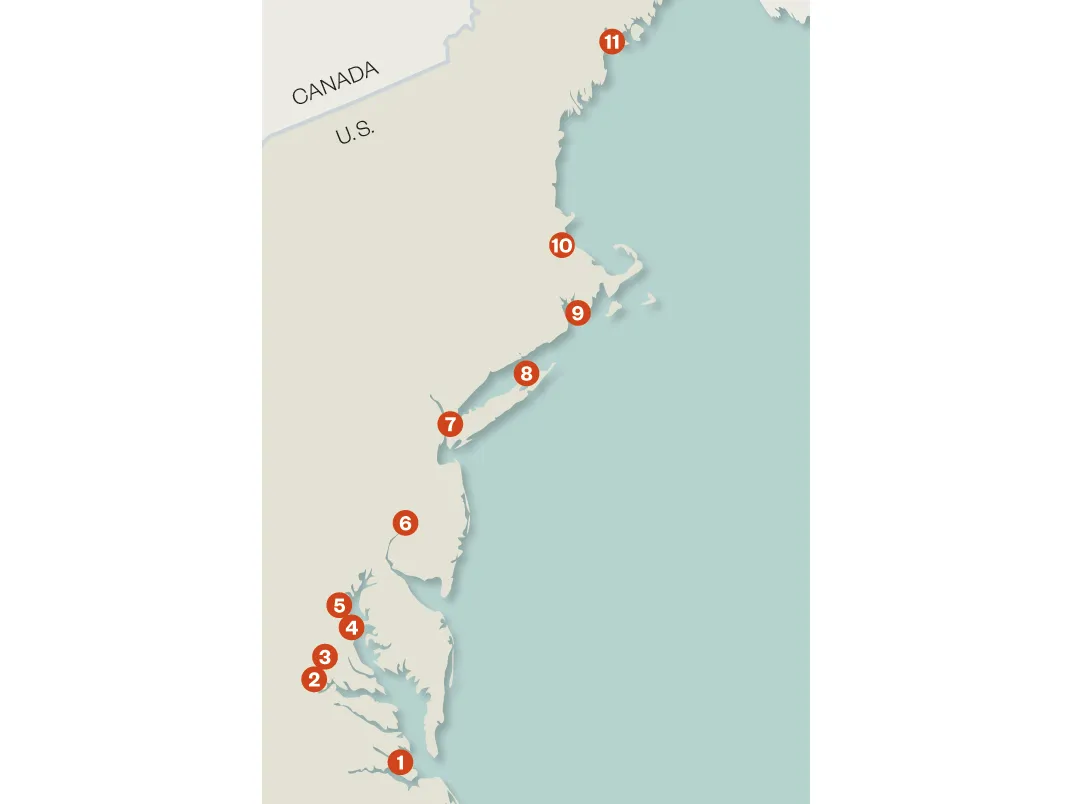

Still, a project that has often been as cash-strapped as Washington’s Continentals has benefited from a brisk American tail wind. After crossing the Atlantic this month, the ship will dock in many of the ports that figured in the Revolution, to welcome the curious aboard to discover a ship lost to history and the young marquis who is a misunderstood American icon.

‘unknown’ works here. Hermione will be unknown to Americans And in Manhattan, the New-York Historical Society is mounting the exhibition “Lafayette’s Hermione: Voyage 2015,” on view May 29 through August 16.

Pretty much everyone in the United States has heard of Lafayette. Scores of towns around the U.S. are named for him, from Fayetteville, North Carolina, to Fayette, Maine, to Lafayette, Oregon (to this list must be added every town named La Grange, after Lafayette’s manse, the Château de la Grange-Bleneau). But the man himself has been swallowed up in a hazy myth surrounding his general helpfulness.

He turns out to be more interesting than his myth, not to mention a good deal quirkier. “Americans don’t in the least know who Lafayette was. The story has been lost in the telling,” says Laura Auricchio, author of a new biography, The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered.

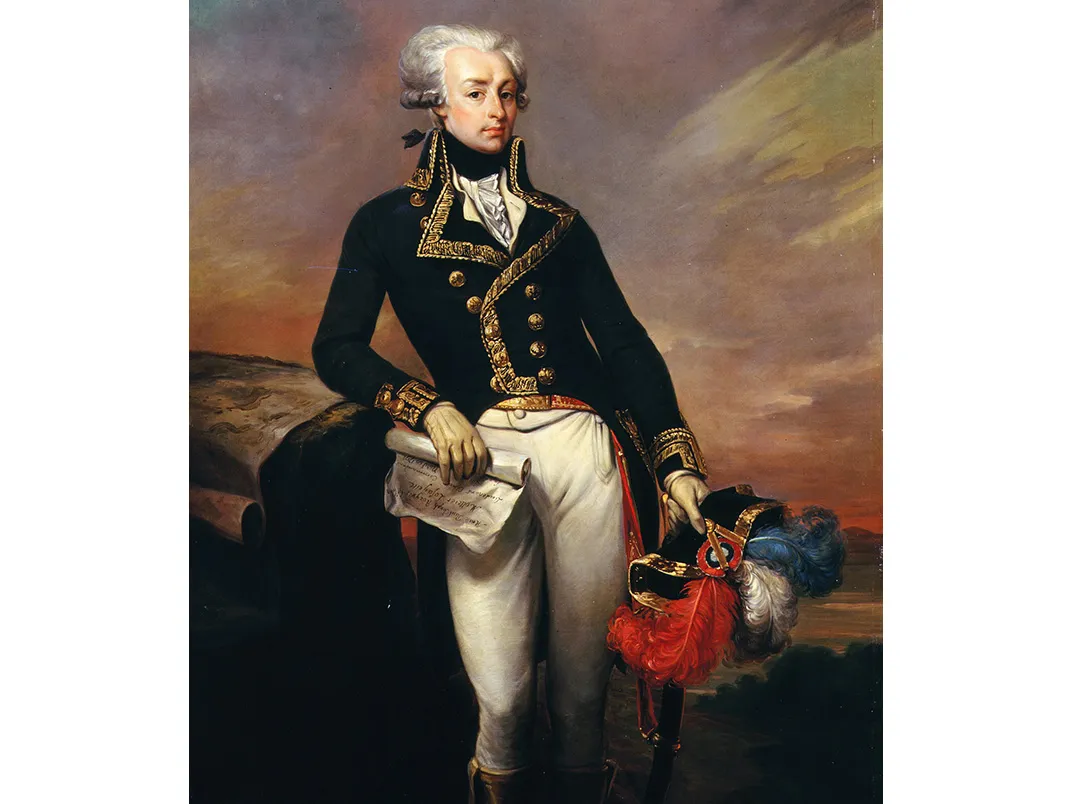

The Marquis de Lafayette who first arrived on U.S. soil in South Carolina on June 13, 1777, was an unformed, untested youth of 19. In a way, he had nowhere else to go. He had been orphaned young—his father was killed when the English crushed the French at Minden in 1759, during the Seven Years’ War. The early death of his parents left him a very rich young man.

In 1774, Lafayette, then 16, was married off to 14-year-old Adrienne de Noailles, who came from one of France’s best-born and most powerful families. The marriage made the provincial Lafayette an instant player at court, but his door pass did him little good. For one thing, he was a lousy dancer. Lafayette himself confessed in his memoirs that he made a clumsy courtier, undone “by the gaucheness of my manners which...never yielded to the graces of the court or to the charms of supper in the capital.”

The match with Adrienne also brought Lafayette a lieutenant’s commission in the Noailles Dragoons, and with it the promise of an army career. But here, too, he hit an unexpected wall. A broad military reorganization in 1775 affected many of France’s existing regiments, Lafayette’s among them. He and many others like him suddenly found themselves sidelined with little hope of advancement.

It was in this context that Lafayette took up America’s fight for freedom. So did many of his frustrated compatriots, whose motives ran the gamut from high-minded to mercenary. “I am well nigh harassed to death with applications of officers to go out to America,” wrote the American diplomat Silas Deane, who worked alongside Benjamin Franklin in Paris to drum up French aid.

Deane and Franklin were pretty picky, and many who asked to fight were turned away. In Lafayette, however, they recognized a pearl of great value—that is to say, great promotional value. In his signed agreement accepting Lafayette’s services and commissioning him an (unpaid) major general, Deane enumerates an unusual list of qualifications for a commanding officer: “high birth, alliances, the great dignities which his family holds at this court, his considerable estates in this realm...and above all, his zeal for the liberty of our provinces.” Thus recommended, the marquis first set sail for America in April 1777.

Lafayette never fully understood that his real job was to help get France into the war, not to fight it himself. Politically, he could be obtuse. “He was an ingénu and quite naive,” says Auricchio. “The opposite of someone like Talleyrand.”

I met with the historian Laurence Chatel de Brancion—who with co-author Patrick Villiers published the French-language biography La Fayette: Rêver la gloire (Dreaming of Glory) in 2013—at her grand apartment near Parc Monceau in Paris. On her father’s side of the family (an ancestor helped found Newport, Rhode Island), Chatel de Brancion is a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Through the French branch of the DAR, she oversaw a donation to the Hermione re-creation project. But when it comes to Lafayette the man, she takes the cold-eyed view often found on her side of the Atlantic. The man often called a “citizen of two worlds” turns out to be a hero in only one of them.

“Lafayette is just an image. He’s the portrait of the terrible inconsequence of the French elite of that period,” Chatel de Brancion tells me. “Franklin used Lafayette, purely and simply. He said, ‘Cover this guy with glory, don’t let him go too near the fighting, and send him back to France full of enthusiasm.’” Moreover, she adds dryly, “Everything the U.S. thanks Lafayette for, it should be thanking Franklin for.”

Maybe so, but nobody will deny that Lafayette played his assigned part perfectly. After an initial chilly reception, he stepped quickly into the role of America’s BFF—Best French Friend. This required a lot more than just showing up. Many of the Frenchmen Silas Deane sent over managed to make themselves deeply unpopular with their haughty manners and their prickly sense of entitlement (Deane later took considerable heat for this).

“These people think of nothing but their incessant intrigues and backbitings,” wrote the German-born French officer Johann de Kalb, the brilliant soldier who came over with Lafayette on the 1777 voyage. “Lafayette is the sole exception....He is an excellent young man.”

The very qualities that made Lafayette a dud at Versailles made him a hit in Boston, Philadelphia and Valley Forge. He was straightforward and enthusiastic. He said what he meant, and then he said it again, and then he said it again. His stubborn optimism in the face of hardship rivaled Candide’s. He was, well, a lot like us. “He had a certain self-deprecating charm, and the ability to make fun of himself, which is not the French style of humor,” says Auricchio.

Crucially, Lafayette won over George Washington, a commander-in-chief with a marked distaste for intimacy and a hostility to the French officer class. In explaining how Lafayette broke the ice, Chatel de Brancion makes much of the fact that Lafayette fought in the blue uniform of a major general in the Continental Army. “We’ve lost the subtlety of that gesture today. Washington was honored that a foreign aristocrat would fight in that uniform—it did him, Washington, enormous credit.”

But clothing alone can’t explain the unusually affectionate bond that sprang up between the two men. Lafayette spent much of the war at Washington’s side and at one point pretty much moved into his house. He named his own son George Washington. By all accounts, the relationship was a bright spot in both their lives. It has withstood the full Freudian treatment over the years; history has yet to find a dark underside to it.

It didn’t hurt that Lafayette happened to be the truest of true believers. Auricchio quotes a French comrade who tries to convince Lafayette to stop being such a sap by believing Americans “are unified by the love of virtue, of liberty...that they are simple, good hospitable people who prefer beneficence to all our vain pleasures.” But that is what he believed, and nothing could convince him otherwise. Lafayette’s American bubble remained unburst to the end.

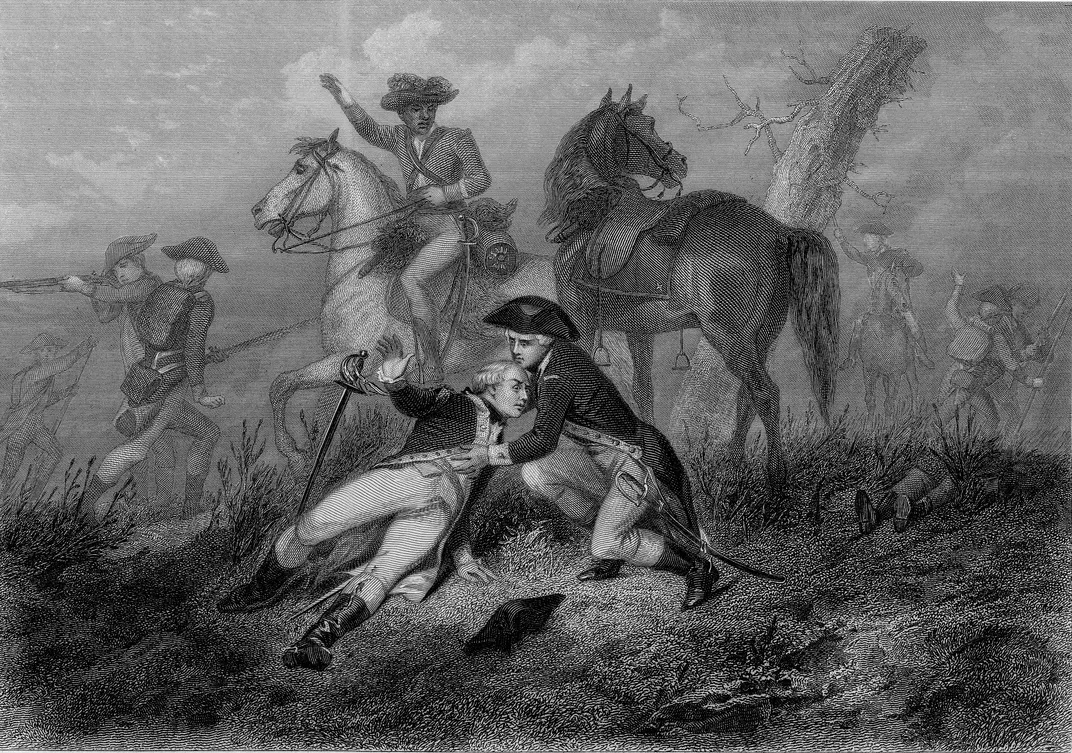

It must be said that battlefield heroics contribute little to Lafayette’s legacy, even though he sought to win glory through force of arms at every opportunity. Whether by circumstance or design—Chatel de Brancion says some of both—Lafayette was rarely put in a position to risk serious harm. Lafayette’s physical courage was beyond question, but his ardor often outweighed his military judgment.

Moreover, as Franklin counseled, it was prudent to protect such a valuable political chess piece. No one wanted Lafayette to meet the fate of his friend de Kalb (DeKalb Avenue, Brooklyn). He was shot and bayoneted repeatedly at the Battle of Camden, dying of his wounds three days later.

Lafayette’s brush with death came at the disastrous Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, when a musket ball passed through the fleshy part of his lower leg. In this, as in so many things, Lafayette had luck on his side. The wound did him little harm (he was treated by Washington’s personal physician) and made him an instant hero.

Another exploit burnished Lafayette’s reputation as a fighting man. On May 20, 1778, Lafayette and his small detachment of Pennsylvania militiamen, at their camp outside Philadelphia, found that they were surrounded by 5,000 redcoats advancing from several directions. Lafayette’s coolness in organizing a retreat in which only nine of his men were killed is nothing short of “miraculous,” writes Auricchio.

In January 1779, with a lull in the fighting, Lafayette sailed back to France, where he continued to knock himself out seeking crucial additional assistance on America’s behalf. (“It is fortunate for the king that Lafayette does not take it into his head to strip Versailles of its furniture, to send to his dear Americans,” the Count de Maurepas remarked in the royal council.)

What Lafayette wanted above all was to return to America in a French uniform at the head of the French expeditionary force forming in early 1780. Instead, the job was given to the battle-hardened Count de Rochambeau. Lafayette’s mission to Washington aboard the Hermione was given to him as a consolation prize.

Capt. Yann Cariou finally found the rough weather he was looking for. Two days after setting out from La Rochelle, he moored the Hermione in a bay off the Crozon peninsula near the northwestern tip of France, almost within sight of where he was born on the Pointe du Raz. These are notoriously angry waters, and they lived up to their billing. All hands welcomed the foul, blustery morning that greeted us the following day.

We sailed out of the bay under a sharp breeze, the Hermione skimming along at ten knots and Mozart’s Symphony No. 25 in G minor cranking on the PA. Everybody was elated. The volunteer crew of men and women mainly in their 20s—French, Swedish, Belgian, German and one American—strained to hoist more sail, eight or ten of them on each line (there were no winches in 1779; the Swedish bosun noted that if a time machine sent him back to the original Hermione, he would make sure to bring a portable winch with him). As instructed, everybody grunted, “Oh! hisse!” in cadence as they pulled. It’s French for “heave ho,” pronounced oh eese; the bosun tells me that you get demonstrably better pulling power if you sing out while you pull.

Before long the wind picked up to Force 8, a gale. The Hermione was slicing through the high swells at 12 or so knots, very fast and close to its top speed. Captain Cariou was smiling broadly as the swells knocked the ship from side to side.

“I’m astonished at what she can do,” says Cariou shaking his head appreciatively. Before he took over as the Hermione’s skipper in 2012, Cariou served as captain of the 167-foot Belem, the French merchant marine’s three-masted training barque. The sluggish Belem was built in 1896 to haul sugar from the West Indies back to France. Cariou was amazed by the difference. “The hull is perfect! She pushes very little water ahead of her, and she chews up very little wake behind.”

The swells had picked up now, and the wind was whistling through the rigging. Some 60 feet up, the crew in yellow slickers was working fast to reef the mainsail while balancing shakily on a slender rope. Looking up I feared for them all, but particularly for the lone American, Adam Hodges-LeClaire from Lincoln, Massachusetts. Adam is a college student obsessed with Revolutionary War history to the point that he sews his own period clothes. He wore nothing else on board, including skimpy leather shoes loosely tied with cord—not the best for keeping a foothold on a madly swaying line. “Please don’t say I’m crazy,” Adam asks me politely. “Say I’m...passionate.”

Several sailors got seasick. “If you can’t handle this, you’re in the wrong business,” says Charlène Gicquel, the pint-size first mate from the English Channel port of Cancale who came over with Cariou from the Belem. “But then,” she adds, “we’re all masochists.”

This was the same kind of weather that the Hermione ran into near the beginning of its 38-day journey across the Atlantic in 1780. The ship’s captain, Louis-René-Madeleine Le Vassor, Comte de Latouche-Tréville, noted the worsening conditions in his log. March 26: “Hermione pitching violently.” March 30: “Wind turns to northwest with strong swells. I note with concern that the ship is straining.”

Poor Lafayette. He was an unhappy sailor even in a calm sea—“I believe we sadden each other, [the sea] and I,” he wrote during his first trip over. Rough water made him violently ill. Laurence Chatel de Brancion envisions Lafayette most likely on deck during the gale, hugging the Hermione’s main mast. That’s what the German charlatan Franz Anton Mesmer recommended as a cure for seasickness. Lafayette was mesmerized—that’s where we get the word—by Mesmer’s crackpot theory of animal magnetism (in fairness, so was half of Europe). Even after Mesmer’s claims had been thoroughly debunked (by Benjamin Franklin, among others) Lafayette may never have stopped believing. “When it came to matters scientific, Lafayette’s enthusiasm sometimes trumped his good sense,” Auricchio writes with some delicacy.

The destinies of Lafayette and the Hermione diverged after Lafayette debarked in Boston on April 28, 1780; he then traveled overland to join Washington at his headquarters in Morristown, New Jersey. The Hermione’s 34-year-old Capt. Latouche-Tréville sailed off to win great renown of his own against the English.

Little more than a month after dropping off Lafayette, Latouche-Tréville sighted the 32-gun English frigate Iris off Long Island. The two warships pounded each other at murderously close range for an hour and a half. Finally, the Iris withdrew, apparently in no shape to continue. The Hermione was badly damaged, and counted 10 dead and 37 wounded. The two captains subsequently argued in the press about who had actually won. But for the current Hermione’s captain, Yann Cariou, the question doesn’t even arise: “We won,” he tells me with a look that made me drop any follow-up questions.

Latouche-Tréville continued to reel off naval victories, often against great odds, in the Hermione and in other ships, during the American Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. On two occasions in 1801, he bloodied the nose of the invincible Lord Nelson. He was supposed to command at Trafalgar, but, alas for France, he died the year before the battle. “If we had had him at Trafalgar, everything would have been different,” insists Cariou, sounding like a die-hard Brooklyn Dodgers fan replaying some of the World Series they lost to the Yankees before 1955.

Lafayette, for his part, wrote to his wife shortly after debarking the Hermione in Massachusetts. “It is to the roar of cannon that I arrive or depart; the principal residents mount their horses to accompany me,” Lafayette reported. “In short, my love, my reception here is greater than anything that I could describe to you.” Did all this adulation go to his head? Yes, it did. An exasperated John Adams, no great fan, wrote in his diary that Lafayette “would be thought the unum necessarium in everything.”

Upon joining Washington in Morristown, Lafayette began agitating for a joint invasion of New York, where the British were strongly entrenched. Rochambeau had to slap him down, more than once. “He forgets that there is still a left flank in a landing, which the whole English Navy will exterminate,” he wrote to another officer.

Rochambeau, along with Washington and the Count de Grasse, commander of the French fleet, opted for bottling up Cornwallis in Yorktown, allowing France to deploy the weight of both its army and its navy in support of Washington’s Continental Army. The outcome speaks for itself. Yorktown briefly reunited Lafayette and the Hermione for the last time: He led 1,200 light infantry to keep Cornwallis busy in Virginia while the French tightened the noose around Yorktown from the sea; the Hermione was part of that noose. The way Laurence Chatel de Brancion sees it, Rochambeau never really got the credit he was due.

History dies hard. “The French still think the Americans should be grateful, because without us, they would never have won the war, which is true,” says Bruno Gravellier, a former naval officer who is the superintendent aboard the Hermione. “It was a long time ago, but I still get a sense of friction between the U.S. and the French sides of the association.”

The remainder of Lafayette’s long life—he died in 1834 at age 76—belongs to the history of France. He unfailingly demonstrated a willingness to rise above the factionalism that gripped France as it headed toward its own revolution.

It sounds good and helps make Lafayette an emotionally sympathetic character, seen from here. But, like many of Lafayette’s best qualities, it earned him little credit in his native land. An aristocratic liberal in the late 1700s and early 1800s was like a Rockefeller Republican today—a chimerical creature unbeloved by those whose differences he tries to split. Even Thomas Jefferson, in 1789, warned Lafayette against attempting to “trim between two sides,” but Lafayette didn’t listen.

When thinking of Lafayette, Americans will always see the fiery youth at Washington’s side, doing his damnedest for our country. Everything else is commentary, and maybe that’s a fair way for an American to look at him.

In the turbulent history of France after Lafayette’s return from America—a period that saw the French Revolution, the rise and fall of Napoleon and the restoration of the monarchy—Lafayette, a son of the Enlightenment and the American Revolution, in public life or private, steadfastly articulated his devotion to one principle: the pursuit of liberty.

Yet the French retain a different image. On July 17, 1791, a large crowd demonstrated on the Champ de Mars in Paris. Lafayette, commander in chief of the new National Guard, brought his troops to maintain order. A thrown rock, a dragoon down, and suddenly the troops opened fire, killing perhaps 100. There were twists and turns to come, but the massacre did incalculable damage to Lafayette’s reputation. “He was catastrophic,” is Chatel de Brancion’s unappealable verdict. Lafayette did remain in the French Army until 1792 and later held office as deputy to the National Convention after the fall of Napoleon in 1815.

As the Hermione at last enters the Gironde estuary, headed for Bordeaux at the end of a week of sea trials, we are suddenly surrounded by dozens of small motor craft and sailboats. The vessels weave in and out, their occupants waving, and blasting their air horns. It’s heady stuff, and it inflated all our spirits.

This must have been something like what Lafayette witnessed as the Hermione sailed into Boston Harbor in 1780. He must have been fairly drunk on it, too, given what Jefferson called his “canine appetite for fame.” But maybe he can be forgiven. In such a moment, you don’t ask yourself what you’ve done to deserve such fanfare. You just smile broadly and think, All this? For me?

Related Reads

The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered