Marching on History

When a “Bonus Army” of World War I veterans converged on Washington, MacArthur, Eisenhower and Patton were there to meet them

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/ca/8bca15db-e553-4633-99db-b26e1b8bb12d/evictbonusarmy.jpg)

Washington, D.C. Chief of Police Pelham D. Glassford was driving south through New Jersey the night of May 21, 1932. Suddenly, a sight appeared in his headlights that he later described as “a bedraggled group of seventy-five or one hundred men and women marching cheerily along, singing and waving at the passing traffic.” One man carried an American flag and another a banner that read, “Bonus or a Job.” Glassford pulled over to have a word with the ragtag group. Atop one of the marchers’ pushcarts, he noted, an infant girl lay sleeping, nestled amid one family’s clothes, oblivious to the ruckus.

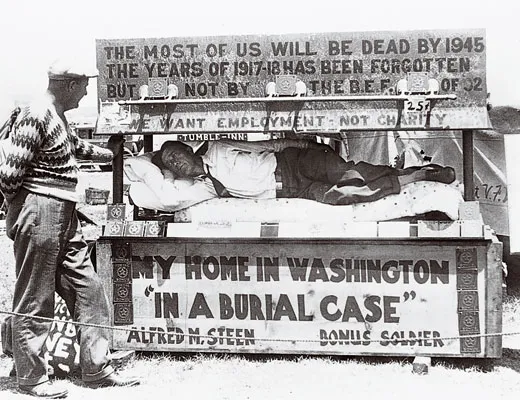

Glassford, who had been the youngest brigadier general in the Army in World War I, understood almost immediately who these wayfarers were. For two weeks or so, newspapers across the nation had begun carrying accounts of marchers bound for the nation’s capital. The demonstrators were part of a growing delegation of veterans and their families heading to Washington to collect payment of the “bonus,” promised eight years before, in 1924, to soldiers who had served in the Great War. (That year, wrangling over the federal budget had ordained that this compensation be deferred until 1945.) Now in 1932, the men, who called themselves the Bonus Army, were dubbing the deferred payment the “Tombstone Bonus,” because, they said, many of them would be dead by the time the government paid it. Glassford drove on to Washington.

By the time he got there, morning newspapers were carrying stories about the progress of the Bonus Army. The Washington Star reported that “One hundred unemployed World War veterans will leave Philadelphia tomorrow morning on freight trains for Washington” and that other vets were converging from as far away as “Portland, Oregon and the Middle West.” The chief was quick to grasp the logistical nightmare he faced. What he could not have seen was that the Bonus Army would help shape several figures who would soon assume larger roles on the world stage—including Douglas A. MacArthur, George S. Patton, Dwight D. Eisenhower and J. Edgar Hoover. The Bonus Army would also affect the presidential election of 1932, when the patrician governor of New York, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, squared off against incumbent President Herbert Hoover, widely blamed for the Great Depression then roiling the country.

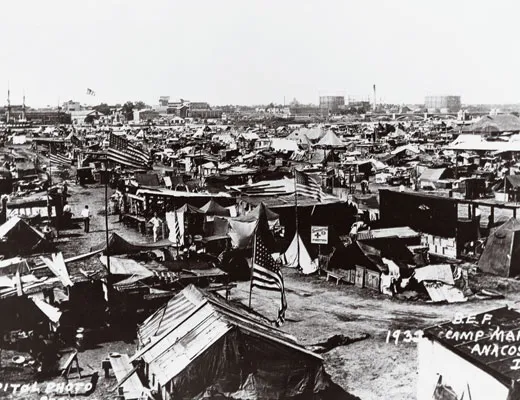

In 1932, nearly 32,000 businesses failed. Unemployment had soared to almost 25 percent, leaving roughly one family out of every four without a breadwinner. Two million people wandered the country in a futile quest for work. Many of the homeless settled in communities of makeshift shacks called “Hoovervilles” after the president they blamed for their plight. Glassford knew he would have to create a sort of Hooverville of his own to house the Bonus Army. But where? In the end he chose a tract of land known as Anacostia Flats, at the outer reaches of the District of Columbia, which could be reached from Capitol Hill only by a wooden drawbridge spanning the Anacostia River.

Glassford oversaw the establishment of the camp as best he could, making sure that at least a certain amount of building materials—piles of lumber and boxes of nails—were supplied. The chief solicited food from local merchants and later added $773 out of his own pocket for provisions. The first contingent of Bonus Army marchers arrived May 23. Over the next two months, an estimated 25,000 more, many with wives and children, arrived to stake their claim to what they felt was their due.

Six years after the end of World War I, Congress responded to vets’ demands that the nation fulfill promises to compensate them by passing a bill granting “adjusted service compensation” to veterans of that war. The legislation was passed over the veto of President Calvin Coolidge, who declared that “patriotism which is bought and paid for is not patriotism.” By the terms of the new law, any veteran who had served in the armed forces was due compensation at the rate of $1 a day for domestic service and $1.25 for each day spent overseas. Those entitled to $50 or less were to be paid immediately; the rest were to receive certificates to be redeemed in 1945.

Nothing much happened until May 1929 (five months before Wall Street’s Black Monday), when Congressman Wright Patman of Texas, himself a war veteran, sponsored a bill calling for immediate cash payment of the bonus. The bill never made it out of committee.

Patman took steps to resurrect the legislation early in the new year of 1932. Then, on March 15, 1932, a jobless former Army sergeant, Walter W. Waters, stood up at a veterans’ meeting in Portland, Oregon, and proposed that every man present hop a freight and head for Washington to get the money that was rightfully his. He got no takers that night, but by May 11, when a new version of the Patman bill was shelved in the House, Waters had attracted a critical mass of followers.

On the afternoon of that same day, some 250 veterans, with only, as Waters would recall later, $30 among them, rallied behind a banner reading “Portland Bonus March—On to Washington” and trekked to the Union Pacific freight yards. Aday later, a train emptied of livestock but still reeking of cow manure stopped to take on some 300 men calling themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force, BEF for short—a play on American Expeditionary Force, the collective name that had been applied to those troops sent over to France.

Sympathetic railroad men, many of them veterans themselves, eased the army’s way eastward. In town after town, well-wishers donated food, money and moral support. Inspired by the Portland group, other Bonus Army units formed throughout the nation. Radio stations and local newspapers carried accounts of the growing contingent headed for their nation’s capital. “The March was a spontaneous movement of protest, arising in virtually every one of the forty-eight states,” observed novelist John Dos Passos, who had served in the Great War with the French Ambulance Service.

As the men headed east, the U.S. Army’s Military Intelligence Division reported to the White House that the Communist Party had infiltrated the vets and was determined to overthrow the U.S. government. The president, however, didn’t take the matter entirely seriously; he called the protest a “temporary disease.”

On May 21, railroad police prevented Waters’ men, who had disembarked when their St. Louis-bound train reached its destination, from boarding eastbound freight trains, departing from just across the Mississippi River on the Illinois shore. In response, the veterans, who had crossed the river by footbridge, uncoupled cars and soaped the rails, refusing to let trains depart. The governor, Louis L. Emmerson, called out the Illinois National Guard. In Washington, the Army deputy chief of staff, Brig. Gen. George Van Horn Moseley, urged that U.S. Army troops be sent to stop the Bonus Marchers, on grounds that by commandeering freight cars, the marchers were delaying the U.S. mail. But the Army chief of staff, a West Point graduate who had commanded the 42nd Division in combat during the Great War, vetoed that plan on the grounds that this was a political, not a military matter. His name was Douglas MacArthur.

The confrontation ended when the veterans were escorted onto trucks and transported to the Indiana state line. This set the pattern for the rest of the march: the governors of Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Maryland, in turn, each sent the veterans by truck on to the next state.

On May 29, the Oregon contingent, including Walter Waters, arrived in Washington, D.C., joining several hundred veterans who had gotten there first. In addition to the main camp in Anacostia, 26 smaller outposts would spring up in various locations, concentrated in the northeast quadrant of the city. There would soon be more than 20,000 veterans in the camps. Waters, the Bonus Army’s “commander in chief,” demanded military discipline. His stated rules were: “No panhandling, no liquor, no radical talk.”

Evalyn Walsh McLean, 45, heiress to a Colorado mining fortune and owner of the famed Hope diamond, had heard the trucks rumbling past her Massachusetts Avenue mansion. After 1 a.m. on a night soon after the vets began pouring into the city, she drove down to the Anacostia camp, where she came upon Chief Glassford, whom she had encountered socially as she moved among Washington’s power elite, just on his way to buy coffee for the men. McLean drove with him to an all-night diner and told an awestruck counterman that she wanted 1,000 sandwiches and 1,000 packs of cigarettes. Glassford placed a similar order for coffee. “We two fed all the hungry ones who were in sight,” McLean recalled later. “Nothing I had seen before in my whole life touched me as deeply as what I had seen in the faces of the Bonus Army.” When McLean learned that the marchers needed a headquarters tent, she had one delivered along with books, radios and cots.

About 1,100 wives and children populated the main camp, making it, with more than 15,000 people, the largest Hooverville in the country. The Bonus Marchers named their settlement CampMarks, in honor of the accommodating police captain S. J. Marks, whose precinct encompassed Anacostia. The vets published their own newspaper (the BEF News), set up a library and barbershop and staged vaudeville shows at which they sang such ditties as “My Bonus Lies Over the Ocean.” “We used to watch them build their shanties,” says then eighth grader Charles T. Greene, now 83, a former director of industrial safety for the District of Columbia who lived just a few blocks from the camp in 1932. “They had their own M.P.s and officers in charge, and flag raising ceremonies, complete with a fellow playing bugle. We envied the youngsters because they weren’t in school. Then some of the parents set up classrooms.”

Almost daily, Chief Glassford visited the camp riding a blue motorcycle. He arranged for volunteer physicians and medical corpsmen from a local Marine Corps reserve unit to hold sick call twice a day. All the veterans, wrote syndicated Hearst columnist Floyd Gibbons, “were down at the heel. All were slim and gaunt. . . . There were empty sleeves and limping men with canes.”

James G. Banks, also 82 and a pal of Greene’s, remembers that neighborhood people “took meals down to the camp. The veterans were welcomed.” Far from feeling threatened, most residents saw bonus marchers as something of a curiosity. “On Saturdays and Sundays, a lot of tourists came down here,” says Banks.

Frank A. Taylor, 99, had just gone to work that summer as a junior curator in the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building. (In 1964 he would become the founding director of the Smithsonian’s Museum of History and Technology, now the National Museum of American History.) “People in Washington were quite sympathetic [to them],” Taylor remembers. “They were very orderly and came in to use the rest room. We did ask that they not do any bathing or shaving before the museum opened.”

While newspaper reporters produced almost daily dispatches on camp life, they largely missed the biggest story of all: in this Southern city, where schools, buses and movies remained segregated, Bonus Army blacks and whites were living, working, eating and playing together. Jim Banks, the grandson of a slave, looks back on the camp as “the first massive integrated effort that I could remember.” Roy Wilkins, the civil rights activist who in 1932 wrote about the camps for The Crisis, the NAACP monthly, noted that “there was one absentee [in the Bonus Army]: James Crow.”

But if the press ignored the integration phenomenon, it made much of a small Communist faction within the ranks of the veterans, giving credence to the official line that had been expressed by Theodore Joslin, who was President Hoover’s press secretary: “The marchers,” he asserted, “have rapidly turned from bonus seekers to communists or bums.”

Meanwhile, at the Justice Department, J. Edgar Hoover, the 37-year-old director of the Bureau of Investigation (the forerunner of the FBI), was coordinating efforts to establish evidence that the Bonus Army had Communist roots—a charge that history does not substantiate.

As rumors about Communist revolutionaries swirled throughout the city, Congress deliberated on the fate of the veterans’ payments. By June 13, Patman’s cash-now bonus bill, authorizing an appropriation of $2.4 billion, finally had made it out of committee and was headed toward a vote. On June 14, the legislation, which mandated the immediate exchange of bonus certificates for cash, came to the floor. Republicans loyal to President Hoover, who was determined to balance the budget, opposed the measure.

Representative Edward E. Eslick (D-Tenn.) was speaking on behalf of the bill when he slumped over and died of a heart attack. Thousands of Bonus Army veterans, led by holders of the Distinguished Service Cross, marched in Eslick’s funeral cortege. The House and Senate adjourned out of respect. The following day, June 15, the House of Representatives passed the bonus bill by a vote of 211 to 176.

The Senate was scheduled to vote on the 17th. Over the course of that day, more than 8,000 veterans gathered in front of the Capitol. Another 10,000 were stranded behind the Anacostia drawbridge, which police had raised, anticipating trouble. Debate continued into the evening. Finally, around 9:30, Senate aides summoned Waters inside. He reemerged moments later to break the news to the crowd: the bill had been defeated.

For a moment it looked as if the veterans would attack the Capitol. Then Elsie Robinson, a reporter for the Hearst newspapers, whispered in Waters’ ear. Apparently taking her advice, Waters shouted to the crowd: “Sing ‘America.’ ” When the veterans ended their song, most of them headed back to camp.

In the days that followed, many bonus marchers returned to their homes. But the fight was not over. Waters declared that he and others intended “to stay here until 1945 if necessary to get our bonus.” More than 20,000 did stay. The hot summer days turned into weeks; Glassford and Waters became concerned about worsening sanitary conditions and the dwindling supply of food in the camps. As June gave way to July, Waters showed up at Evalyn Walsh McLean’s front door. “I’m desperate,” he said. “Unless these men are fed, I can’t say what won’t happen in this town.” McLean telephoned Vice President Charles Curtis, who had attended dinner parties at her mansion. “Unless something is done for [these men],” she informed Curtis, “there is bound to be a lot of trouble.”

Now more than ever, President Hoover, along with Douglas MacArthur and Secretary of War Patrick J. Hurley, feared that the Bonus Army would turn violent, perhaps triggering uprisings in Washington and elsewhere. Vice President Curtis was particularly unnerved by the sight of veterans near his Capitol Hill office July 14, the anniversary of the day the mobs stormed France’s Bastille.

The three commissioners, appointed by Hoover, who administered the District of Columbia (in lieu of a mayor) were convinced the threat of violence was growing by the day. They worried most about veterans occupying a series of dilapidated, government-owned buildings—and tents, shanties and lean-tos arrayed around them—on Pennsylvania Avenue near the Capitol. Hoover told the commissioners that he wanted these downtown veterans evicted. The commissioners set the ouster for July 22. But Glassford, hoping the vets would leave voluntarily, managed to postpone their expulsion by six days.

On the morning of July 28, Glassford arrived with 100 policemen. Waters, speaking as the vets’ leader, informed him that the men had voted to remain. At 10 a.m. or so, the policemen roped off the old armory; the vets backed down and left the building. Meanwhile, thousands of marchers, in a display of solidarity, had begun massing nearby. Just after noon, a small contingent of vets, pressing forward in an attempt to reoccupy the armory, were stopped by a phalanx of policemen. Someone—no one knows who—began throwing bricks, and policemen began swinging their nightsticks. Even though several officers were injured, no shots were fired and no police pistol was unholstered. One vet ripped Glassford’s badge from his shirt. In a matter of minutes, the fight was over.

The scene remained quiet until shortly after 1:45 p.m., when Glassford noticed vets skirmishing among themselves in a building adjacent to the armory. Several policemen went in to break up that fight. Accounts differ as to what happened next, but shots rang out. When the ensuing melee ended, one veteran lay dead, another mortally wounded. Three policemen were injured.

For two months, General MacArthur, anticipating violence, had been secretly training his troops in riot control. By the time the deadly conflict commenced, MacArthur, acting on orders from the president, had already commanded troops from Fort Myer, Virginia, to cross the Potomac and assemble on the Ellipse, the grassy lawn across from the White House. His principal aide, Maj. Dwight D. Eisenhower, urged him to stay off the streets and delegate the mission to lower-ranking officers. But MacArthur, who ordered Eisenhower to accompany him, assumed personal command of the long-planned military operation.

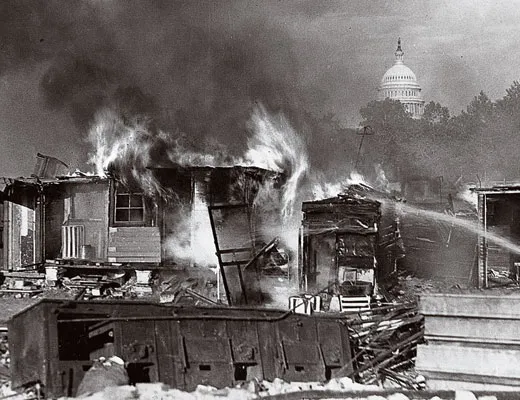

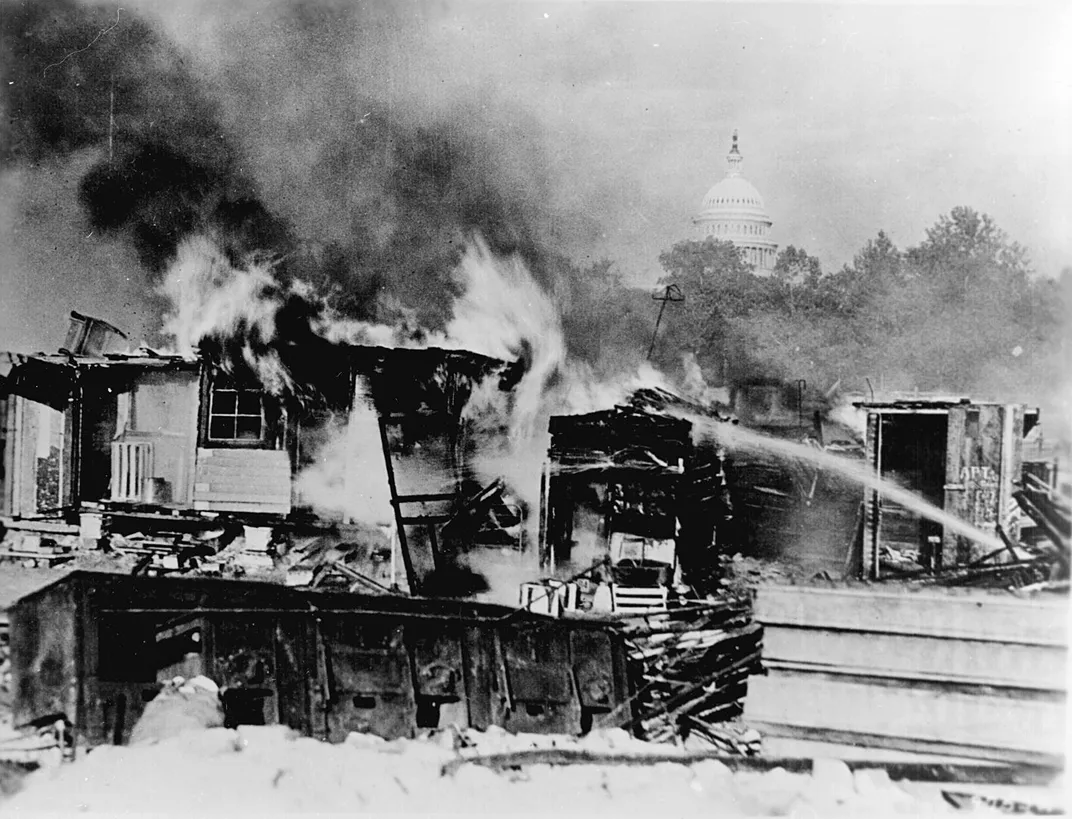

What happened next is etched in the American memory: for the first time in the nation’s history, tanks rolled through the streets of the capital. MacArthur ordered his men to clear the downtown of veterans, their numbers estimated at around 8,000, and spectators who had been drawn to the scene by radio reports. At 4:30 p.m., nearly 200 mounted cavalry, sabers drawn and pennants flying, wheeled out of the Ellipse. At the head of this contingent rode their executive officer, George S. Patton, followed by five tanks and about 300 helmeted infantrymen, brandishing loaded rifles with fixed bayonets. The cavalry drove most pedestrians—curious onlookers, civil servants and members of the Bonus Army, many with wives and children—off the streets. Infantrymen wearing gas masks hurled hundreds of tear-gas grenades at the dispersing crowd. The detonated grenades set off dozens of fires: the flimsy shelters veterans had erected near the armory went up in flames. Black clouds mingled with tear gas.

Naaman Seigle, now 76, was 6 years old that day. He remembers a detachment of cavalry passing in front of his house in southwest D.C. that morning. “We thought it was a parade because of all the horses,” he says. Later in the day, the boy and his father happened to go downtown to a hardware store. As they emerged from the shop, they saw the tanks and were hit with a dose of tear gas. “I was coughing like hell. So was my father,” Seigle recalls.

By 7:00 p.m., soldiers had evacuated the entire downtown encampment—perhaps as many as 2,000 men, women and children—along with countless bystanders. By 9:00, these troops were crossing the bridge to Anacostia.

There, Bonus Army leaders had been given an hour to evacuate the women and children. The troops swooped down on CampMarks, driving off some 2,000 veterans with tear gas and setting fire to the camp, which quickly burned. Thousands began the trek toward the Maryland state line, four miles away, where National Guard trucks waited to drive them to the Pennsylvania border.

Eyewitnesses, including Eisenhower, insisted that Secretary of War Hurley, speaking for the president, had forbade any troops to cross the bridge into Anacostia and that at least two high-ranking officers were dispatched by Hurley to convey these orders to MacArthur. The general, Eisenhower later wrote, “said he was too busy and did not want either himself or his staff bothered by people coming down and pretending to bring orders.” It would not be the last time that MacArthur would disregard a presidential directive—two decades later President Truman would fire him as commander of U.N. military forces in South Korea for doing just that. (Truman explicitly ordered that Chinese bases in Manchuria should not be bombed, a move that would have caused China to escalate even further its role in the Korean conflict. MacArthur, operating in defiance of the president, attempted to convince Congress that such action should be taken.) Recalling the Bonus Army incident during an interview with the late historian Stephen Ambrose, Eisenhower said: “I told that dumb son-of-a-bitch he had no business going down there.”

Around 11:00 p.m., MacArthur called a press conference to justify his actions. “Had the President not acted today, had he permitted this thing to go on for twenty-four hours more, he would have been faced with a grave situation which would have caused a real battle,” MacArthur told reporters. “Had he let it go on another week, I believe the institutions of our Government would have been severely threatened.”

Over the next few days, newspapers and theater newsreels showed graphic images of fleeing veterans and their families, blazing shacks, clouds of tear gas, soldiers wielding fixed bayonets, cavalrymen waving sabers. “It’s war,” a narrator intoned. “The greatest concentration of fighting troops in Washington since 1865. . . . They are being forced out of their shacks by the troops who have been called out by the President of the United States.” In movie theaters across America, the Army was booed and MacArthur jeered.

Democratic presidential nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt opposed immediate payment of the bonus on grounds that it would favor a special class of citizen at a time when all were suffering. But after reading newspaper accounts of MacArthur’s eviction, he told an adviser that “this will elect me.”

Indeed, three months later, Roosevelt would win the election by seven million votes. George Patton, discounting the effect of the Great Depression on voters, later said that the Army’s “act[ing] against a crowd rather than against a mob” had “insured the election of a Democrat.” Hoover biographer David Burner agrees the incident dealt a final blow to the incumbent: “In the minds of most analysts, whatever doubt had remained about the outcome of the presidential election was now gone: Hoover was going to lose. The Bonus Army was his final failure, his symbolic end.”

Just months into FDR’s first term, in March 1933, bonus marchers began drifting back into Washington. By May, some 3,000 of them were living in a tent city, which the new president had ordered the Army to set up in an abandoned fort on the outskirts of Washington. There, in a visit arranged by the White House, the nation’s new first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, braved mud and rain to join the vets in a sing-along. “Hoover sent the Army; Roosevelt sent his wife,” said one vet. By June 1933, about 2,600 vets had accepted FDR’s offer of work in a New Deal public works program called the Civilian Conservation Corps, though many others rejected the $1-a-day wage, calling it slavery.

Beginning in October 1934, Roosevelt, attempting to deal with the jobless remnants of the Bonus Army, created “veterans’ rehabilitation camps” in South Carolina and Florida. In Florida, 700 men filled three work camps in Islamorada and Lower Matecumbe in the Florida Keys, building bridges for a highway that would extend from Miami to Key West.

The men had been working all summer and looked forward to the Labor Day weekend. About 3oo of them went on furlough, many to Miami. But on September 2, 1935, a hurricane unlike any recorded in the United States slammed into the Upper Keys where they were camped. Wind gusts were estimated at 200 miles an hour—enough to turn granules of sand into tiny missiles that blasted flesh from human faces.

Because it was a holiday weekend, the work-camp trucks that might have carried the veterans north to safety were locked. A train sent to rescue them was first delayed, then, just a couple of miles from camp, derailed by the storm surge. It never reached the men. With no way to flee, at least 256 veterans and many locals were killed. Ernest Hemingway, who rushed to the ghastly scene from his home in Key West, wrote that “the veterans in those camps were practically murdered. The Florida East Coast [Railroad] had a train ready for nearly twenty four hours to take them off the Keys. The people in charge are said to have wired Washington for orders. Washington wired the Miami Weather Bureau which is said to have replied there was no danger and it would be a useless expense.” In fact, the failure to rescue the men was not as callous as Hemingway claimed, though there is no question that a series of bureaucratic bungles and misunderstandings in Miami and Washington contributed to the calamity—the Bonus Marcher’s final, and in many cases, fatal indignity.

In 1936, Wright Patman reintroduced the cash-now bonus act, which finally became law. Senator Harry S. Truman of Missouri, an unflinching New Deal loyalist and a combat veteran of World War I, defied his president in supporting the bonus. In June 1936, the first veterans began cashing checks that averaged about $580 per man. Ultimately, nearly $2 billion was distributed to 3 million World War I veterans.

In 1942, soon after Pearl Harbor, legislation was introduced in Congress to provide benefits for the men and women of World War II. The law, known as the G.I. Bill of Rights, would become one of the most important pieces of social legislation in American history. Some 7.8 million World War II veterans took advantage of it in academic disciplines as well as paid on-the job training programs. It also guaranteed ex-servicemen loans to buy homes or farms or start businesses. The G.I. Bill helped create a well-educated, well-housed new American middle class whose consumption patterns would fuel the postwar economy.

President Roosevelt, overcoming his long-standing opposition to “privileges” for veterans, signed the “Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944,” as the G.I. Bill was called, on June 22. At that moment, Allied troops were liberating Europe under Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. One of his generals, George S. Patton, was leading troops toward the Seine, while Douglas MacArthur was planning the liberation of the Philippines. For the three by-then legendary figures, the Bonus March had receded into the past, a mostly embarrassing incident, largely forgotten. If character is destiny, however, the major players in that drama had enacted, in cameo, the defining roles they would soon assume on the stage of the 20th century.