The Mad King and Magna Carta

How did a peace treaty signed — and broken — more than 800 years ago become one of the world’s most influential documents?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3d/6f/3d6f5c5b-a3ec-4699-acae-0f3cd29413c5/julaug2015_i09_magnacarta.jpg)

We parked near a meadow, tramped through a damp cow field and stood in the shadow of one of Britain’s oldest living things. The Ankerwycke Yew is 2,000 years old: a gnarled beast of a tree with a trunk ten feet wide and thick branches spilling out fronds of spiny, dark-green needles. Romantic legend holds that Henry VIII courted Anne Boleyn beneath its boughs. It grows on the north bank of the Thames upstream from London, in the county of Surrey. Nearby are the ruins of a 12th-century priory, a couple of large water reservoirs and Heathrow Airport. Every 90 seconds a plane roars overhead. In the distance we could hear traffic on the M25, the motorway that encircles London, but across the river it was calm. Over there was Runnymede, a low-lying, lush green meadow cut through and watered by the Thames. The ground is soft and muddy; stand too long and your boots will start to sink. The foot traffic that morning consisted mostly of dog walkers. There was little to indicate that we were near the spot where, 800 years ago, King John agreed to a peace treaty with his rebellious barons. Today we call that agreement Magna Carta.

If we had stood beside the younger, smaller Ankerwycke Yew on Monday, June 15, 1215, we would have witnessed a busier and more dangerous Runnymede. The treaty was struck on the brink of civil war. The conference that produced it was tense. Dozens of earls, barons and bishops attended, all with their own military followings. The chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall wrote that these rebels “gathered with a multitude of most famous knights, armed well at all points.” They camped in tents on one side of the meadow. On the other side stood large royal pavilions, which would have soared into the air with John’s standards depicting three lions embroidered in gold fluttering above. When the king came down to the conference he traveled, probably by barge, from his fiercely defended castle upriver at Windsor. He didn’t want to come. It was said by another chronicler that although he may have been charming during negotiations, behind the scenes “he gnashed his teeth, rolled his eyes, grabbed sticks and straws and gnawed them like a madman.” The tantrums did him no good. Although John did not know it at the time, when he agreed to put his seal to Magna Carta, he was both limiting forever the rights of kings to place themselves above the law and creating the most famous constitutional document in the English-speaking world.

**********

The world had written laws long before King John and Magna Carta. The commandments handed down by God to Moses, the Roman Code of Justinian and the Salic law of Germanic France had all laid out basic rules for human society, and they were kept in written form for reference in the case of dispute. Stone tablets survive from Mesopotamia bearing laws written in Sumerian around 2100 B.C. Magna Carta, which comprises 63 clauses spelling out in dense legalese some of the basic laws of medieval England, and which is often thought of as England’s first statute, fits into this tradition.

Yet England in the 13th century was in no sense lawless. If anything, it was one of the most deeply governed places on earth. From at least the time of Alfred the Great (A.D. 871-899) and most likely long before, English law had been codified, written down and pretty efficiently enforced. When the Normans invaded England in 1066, they continued to issue written legal codes, often when a new king was crowned. John’s father, Henry II (1133-1189), had been a particularly enthusiastic legal reformer. He created swaths of new legal processes and is often described as the father of English common law, that body of custom and precedent that complements statutory law. So the point of Magna Carta in 1215 was not to invent laws to fill the vacuum of anarchy. Rather, it was to restrain a king who was using his legal powers rather too keenly.

John was born in 1167. He was his father’s youngest son, and although the Plantagenet dynasty established by Henry II had lands stretching from the borders of Scotland to the Pyrenees, John as a prince had no territories to call his own. He was nicknamed John Lackland. He was called plenty of other names, too. The chronicler Gerald of Wales condemned him as a “tyrannous whelp.” William of Newburgh said he was “nature’s enemy.” The French poet Bertrand de Born judged that “no man may ever trust him, for his heart is soft and cowardly.” From a very early age John was recognized as sly, conniving, deceitful and unscrupulous.

Still, bad character was no impediment to being king. John inherited the throne in 1199, after his heroic and much-admired elder brother Richard I, “the Lionheart,” died of gangrene after he was shot with a crossbow bolt during a siege. Almost immediately things went wrong. The Plantagenet empire included or controlled the French territories of Normandy, Brittany, Anjou, Maine, Touraine and Aquitaine—about a third of the territorial mass of modern France and virtually the entire western seaboard. During the first five years of John’s reign the bulk of this was lost, in large part thanks to his insipid military command. The most traumatic loss was that of Normandy, conquered by the French in 1204. This was a terrible humiliation, and it had two important consequences. First, John was now forced to spend almost his entire reign in England (his father and brother had spent most of their reigns abroad), where his disagreeable personality brought him into regular conflict with his barons. Second, John’s determination to reconquer Normandy and the rest of his lost French lands drove him to an extortionate form of government. He devoted himself to squeezing as much money as humanly possible out of his subjects, particularly his barons and the Church.

**********

John was a legal whiz. He knew the machinery of government inside-out and the best ways to manipulate it to take his subjects’ money. He would entangle his barons in massive debts to the crown and then use the courts to strip their wealth, often ruining them forever. As king he was entitled to charge his nobles fees known as “fines” for inheriting lands and titles and getting married. There was an understanding that these would be levied at reasonable rates, but John ignored it and charged some mind-blowing sums. In 1214 he charged one man £13,333—something like $17 million or more today—for permission to marry. John also set the military tax known as “scutage,” by which a knight could buy his way out of military service to the crown, at an exorbitant rate. And he charged huge fees for his subjects to obtain justice in his courts.

Besides this racketeering, John also earned a reputation as vindictive and even murderous. It was believed that in 1203 he killed his nephew and rival, Arthur of Brittany. One chronicler heard that John had done the deed himself, “after dinner, when he was drunk and possessed by the devil,” and thrown the body into the Seine. In 1208 John fell out with a close associate named William de Braose and pursued his family to destruction, starving to death William’s wife and eldest son in the dungeons of his castle. (William died in exile in France.) John mistreated hostages given to him as security for agreements: The knight William Marshal said he “kept his prisoners in such a horrible manner and in such abject confinement that it seemed an indignity and a disgrace to all those with him.” And it was rumored that he made lecherous advances on his barons’ wives and daughters.

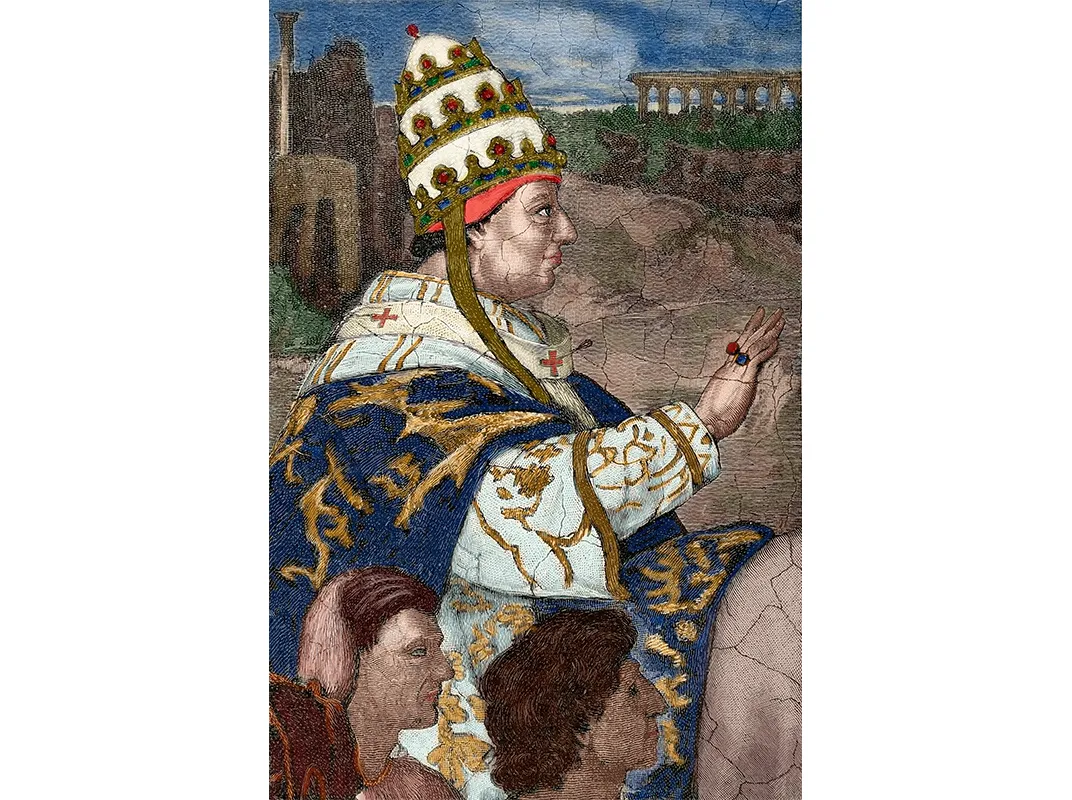

Then there was the Church. In 1207 John fell out with Pope Innocent III over the appointment of a new archbishop of Canterbury. The king claimed the right to approve the appointment; so did the pope. A bitter standoff ensued. Innocent first placed England under interdict—a sentence banning all church services. Later he personally excommunicated John. It took six years to resolve this power struggle, during which time John seized Church lands and property and confiscated the vast revenues of his bishops, most of whom fled the country. This made John rich but earned him the lasting hatred of almost everyone connected with the Church. Fatally for his reputation, that included the monastic chroniclers who would write most of the contemporary histories of the reign. A typical judgment was given by the 13th-century writer Matthew Paris, in an epitaph for the king: “Foul as it is, hell itself is defiled by the fouler presence of John.”

In 1213 Pope Innocent, tired of being ignored, asked the king of France to invade England and depose the faithless king. Finally, John backed down and reconciled with Rome. Later he even promised (probably in bad faith) to lead a new crusade to Jerusalem. But his abrasive methods had earned him the undying hatred of a large group of English barons, particularly in the north of the realm. In 1214 they had their chance to strike. John gambled all of his ill-gotten wealth on a military campaign to win back Normandy. It failed spectacularly when his allies were crushed by the French at the Battle of Bouvines on July 27, 1214. “And thereafter began the war, the strife and criminal conflict between the King and the barons,” wrote a contemporary historian. John returned home that autumn to find rebellion brewing. Insurgents were demanding that the king produce a charter promising to mend his ways, to stop abusing Church and aristocracy, and to govern in accordance with his own law, which they should help make. If he failed to do so, they would depose him and invite a new king to take his place.

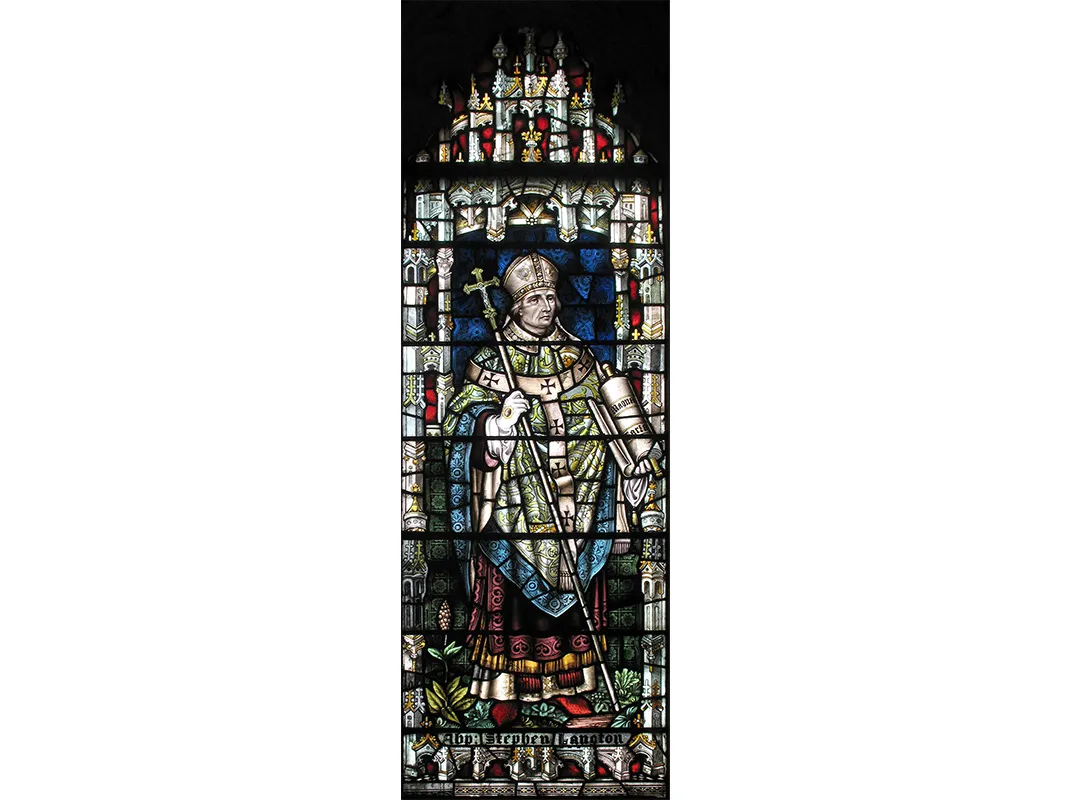

These rebels, calling themselves the Army of God, finally took up arms in the spring of 1215 and seized control of London. This is what forced John to assent to Magna Carta at Runnymede that June. The agreement followed lengthy discussions mediated by the archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton. When it was written down it came to about 4,000 words, now conventionally divided into 63 clauses. They covered a wide range of issues. The king conceded that the English church would be free from government interference, as would the City of London. He promised to cap military taxes and the fines he levied on his barons for inheritance and marriage.

He dealt with scores of other issues, large and small. John promised to eject foreign mercenaries from England, and he promised to remove the fish traps that obstructed rivers near London and blighted water transport. Most important of all, in Clauses 39 and 40 he promised that “no free man is to be arrested or imprisoned or stripped of his possessions or outlawed or exiled or in any other way ruined, nor will we go or send against him except by the legal judgment of his peers or by the law of the land. To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice.”

News of this extraordinary charter traveled fast. A Scottish chronicle from the time records that “A strange new order began in England; Whoever heard of such a thing? For the body longed to govern the head, And the people wished to rule the king.” The charter itself was widely distributed, too. Royal scribes made at least 13 copies, and perhaps as many as 40. Each was authenticated with the king’s royal seal. (He never signed Magna Carta.) They were then distributed around England, probably via the bishops, who stored them in their cathedrals. Today, only four survive.

**********

One morning in early February this year I took a taxi to the British Library in London to meet the curator of medieval manuscripts, Claire Breay. Even though it was around seven o’clock, there was an air of excitement in the library’s Treasures Gallery. TV crews were set up, ready for live broadcasts. We were there to witness a unique event. The four surviving copies of King John’s Magna Carta were going on display together. It was the first time in 800 years that the four pieces of parchment had been in the same room.

The next day 1,215 people, selected by lottery, came to the library to see them. Later in the week the charters were taken to the Houses of Parliament. Then they were returned to their permanent homes: Two are kept in the British Library, one is owned by Lincoln Cathedral and displayed at the nearby castle, and one belongs to Salisbury Cathedral. (That’s why Jay-Z made a private pilgrimage to Salisbury Cathedral to mark the U.K. launch of his 2013 album, Magna Carta...Holy Grail. The British Library turned him down.)

Viewed next to one another, it was surprising how different the charters were. There is no “original” Magna Carta: The surviving charters from 1215 are “engrossments,” or written records of an oral agreement. Their text is virtually identical—heavily abridged Latin written in ink made from oak galls on parchment of dried, bleached sheepskin. Each charter is a different size and shape—one almost square, two “portrait” and one “landscape.” The Salisbury charter is written in dark ink and a sort of handwriting more typically seen in 13th-century Bibles and psalters than on legal documents. The other three are in a paler “chancery hand,” the script used on official documents by the king’s full-time scribes.

One of the British Library copies still retains its seal, although what was once a fine piece of red wax impressed on both sides with images of the king triumphant was melted in a library fire in 1731 and is now a shapeless brown blob. The charter to which it is attached is also in rotten condition. A ham-fisted attempt in the 1830s to preserve it had the opposite effect: The parchment has been flattened, half-dissolved and glued to a thick backing board. Most of the ink has been washed off and can be seen only using multispectral imaging techniques.

I found the sight of all these charters together thrilling, and I was not alone. At a reception for VIPs that evening, the queue of professors, bishops and politicians snaked out of the gallery and through the library’s main atrium. On a video screen dignitaries from around the world paid homage to the charter; they included Aung San Suu Kyi; the former British secretary of state, William Hague; and the U.S. Supreme Court justice Stephen Breyer. The next day, when the 1,215 public ballot winners came to see the charters, a young couple outside the library told me they had found the experience at the exhibition “deeply moving.”

In a sense it is a miracle that Magna Carta survives at all. As soon as he had granted the charter at Runnymede, John wrote to the pope and had it annulled. The civil war that the charter was intended to halt therefore began. During the course of it John died of dysentery. The noblemen governing England on behalf of his young son, Henry III, reissued the charter in 1216 and again in 1217 to show that they were willing to govern in good faith. The second reissue was accompanied by the Charter of the Forest, which codified law in royal woodlands, softened the punishments for poaching and reduced the area of English countryside designated as royal forest land. To differentiate between the two agreements, people began to refer to the original charter as Magna Carta.

The legend of Magna Carta began to grow. During the 13th century it was reissued several times. Sometimes the barons demanded it as a quid pro quo for agreeing to support royal military expeditions. Sometimes the crown regranted it to settle political crises. In all, 24 of these medieval editions survive, including the fine 1297 edition that was bought at auction for $21.3 million by the American financier David Rubenstein in 2007 and is on permanent loan to the United States in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. The most recent edition to come to light was discovered just in February, tucked into a Victorian scrapbook in the archives of the British seaside town of Sandwich. Even badly damaged, it was estimated to be worth about $15 million.

By the end of the 13th century Magna Carta’s terms were becoming less important than its symbolic weight—the crown’s acknowledgment that it was bound by the law. Though Magna Carta may not have been much cared-for during the Tudor years of the 16th century—Shakespeare’s play King John makes no mention of the great charter, concentrating instead on Arthur of Brittany’s death—it roared back into life in the 17th century. The great lawyer and radical politician Sir Edward Coke made Magna Carta the foundation of his opposition to Charles I—who lost his head in 1649 for refusing to accept that he should be bound by the law.By then the document’s influence was spreading beyond the British Isles; clauses from Magna Carta were written into statutes governing the American colonies from as early as 1639. Later, when the people of Massachusetts rebelled against the Stamp Act, they pointed out that it violated the core principles of “the great Charter.” When the colonies overthrew British rule altogether, the Declaration of Independence condemned George III for obstructing the administration of justice, “for imposing Taxes on us without our Consent; for depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of trial by jury” and for “transporting large armies of foreign mercenaries to complete the works of death, desolation and tyranny.” Nearly identical complaints had been lodged against King John 561 years before. Magna Carta also influenced the state-building that followed. Article III of the Constitution stipulates that “the trial of all crimes, except in cases of impeachment, shall be by jury,” and Articles V and VI of the Bill of Rights—which hold, respectively, that “No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury...nor be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law” and that “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial”—are essentially paraphrases of Magna Carta Clauses 39 and 40.

Around the world, from Canada to Australia, other founding constitutional texts also leaned heavily on Magna Carta. Parts of the charter can be found in the European Convention on Human Rights and in the U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which Eleanor Roosevelt called “a Magna Carta for mankind.”

**********

Back at Runnymede there is surprisingly little in the way of monuments to the charter. The American Bar Association has put up a small stone structure there with eight pillars, a saucer-shaped roof and a stone stump bearing an inscription: “To Commemorate Magna Carta: Symbol of Freedom Under Law.” The British have erected nothing major. The closest they got was when the radical politician Charles James Fox proposed putting up a gigantic pillar to commemorate the centennial of the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89. The proposal failed, but it was just as well: Runnymede is on a flood plain. Had it been built, the pillar would have probably sunk into the marshy ground.Plenty of pageantry has already greeted the eighth centenary. The British Library’s current exhibition displays its two copies of the 1215 Magna Carta alongside Thomas Jefferson’s handwritten Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights, on loan from the New York Public Library and the National Archives, respectively. Almost every town with even the slightest connection to Magna Carta is hosting an event. Medieval fairs are planned. Magna Carta beer is being brewed. A giant embroidery of the Magna Carta Wikipedia page, designed by the artist Cornelia Parker, is on exhibit at the British Library. Salisbury Cathedral will feature a king-size Magna Carta cake iced with a transcription of the original Latin.

Profound or parochial, it all matters. The celebrations will not simply mark the granting of the charter, which in 1215 was really a short-lived peace treaty issued in bad faith by a grudging monarch. Rather, the celebrations will pay tribute to law, liberty and the principles of democracy that take Magna Carta as their starting point.

Related Reads

Magna Carta: The Making and Legacy of the Great Charter