Kon-Tiki Sails Again

A new film recreates the epic voyage—and revives the controversy over its legendary leader, Thor Heyerdahl

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Kon-Tiki-crew-member-dives-631.jpg)

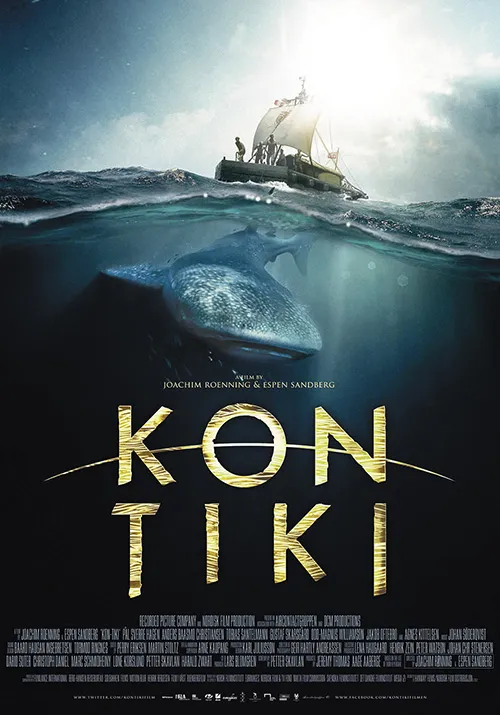

The most harrowing scene in Kon-Tiki, the new Oscar-nominated Norwegian film about the greatest sea voyage of modern times, turns out to be a fish story. In the 2012 reconstruction of this 1947 adventure, six amateur Scandinavian sailors—five of whom are tall, slim and valiant—build a replica of an ancient pre-Incan raft, christen it Kon-Tiki and sail westward from Peru along the Humboldt Current for French Polynesia, more than 3,700 nautical miles away. In mid-passage, their pet macaw is blown overboard and gobbled up by a big bad shark. During the scene in ques- tion, one of the tall and slim and valiant is so enraged by the bird’s death that he thrusts his bare hands into the Pacific, hauls in the shark and guts it with a savagery that would have made Norman Bates envious.

The shark’s blood seeps through the balsa timbers of the Kon-Tiki, inciting a feeding frenzy down below. Meanwhile, the sixth crewmate—this one short, plump and craven—slips off the edge of the raft, which can neither stop nor turn back. As it drifts away from the drowning fat man, his slim companions frantically distract the crazed sharks with chunks of flesh. Then one seaman plunges to the rescue bearing a life belt secured to the raft by a long line. After several stomach-churning seconds Skinny reaches Fatty, and the others yank them in before they become Shark Bites.

It hardly matters that there never was a fat guy or a vengeful seaman, and that the munched macaw was really a parrot that vanished without drama into salt air. Like Lincoln, the film takes factual liberties and manufactures suspense. Like Zero Dark Thirty, it compresses a complex history into a cinematic narrative, intruding on reality and overtaking it. The irony is that the epic exploits of the Kon-Tiki’s crew had once seemed untoppable.

From the get-go, anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl, the expedition’s charismatic and single-minded leader, had touted the voyage as the ultimate test of nerve and endurance. His daring travel adventure sparked a spontaneous media circus that turned him into a national hero and a global celebrity.

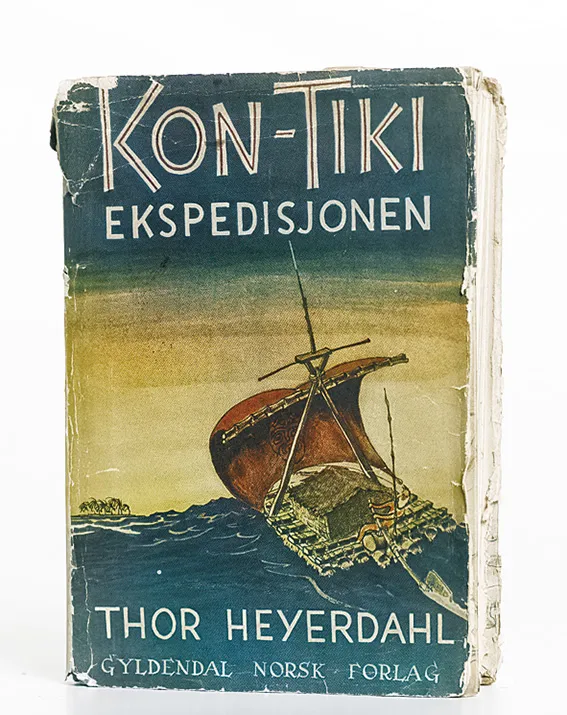

In Heyerdahl’s 1950 Kon-Tiki, Across the Pacific by Raft—a lively chronicle that sold more than 50 million copies and was translated into nearly 70 languages—and his 1950 Academy Award-winning documentary Kon-Tiki, the sailors were presented as 20th-century Vikings who had conquered the vast, lonely Pacific. The new movie elevates them from Vikings to Norse gods. “Thor had a special feeling of greatness about him,” says Jeremy Thomas, one of the film’s producers. “He was more than merely brave and courageous: He was mythic.”

Kon-Tiki is a gloss on a man whose towering self-regard allowed him to ignore critics who insisted he was on a suicide mission. Was the voyage a genuine scientific breakthrough or a rich kid’s diversion? By making Heyerdahl mythic and sidestepping the shifting layers of truth in his feats and scholarship, the filmmakers beg a reappraisal of his perch in popular consciousness.

***

The myth of the Kon-Tiki begins during the late 1930s on the South Pacific island of Fatu Hiva, in the Marquesas chain. It was there that Heyerdahl and his new bride, Liv, took a yearlong honeymoon to research the origins of Polynesian animal life. While lying on a beach, gazing toward America, the University of Oslo-trained zoologist listened to a village elder recite the legends of his ancestors, towheaded men who arrived with the sun from the east. Their original home was high in the clouds. Their chieftain’s name was Tiki.

To Heyerdahl, the people described by the village elder sounded a lot like the fair-skinned Peruvians who were said in oral tradition to have lived by Lake Titicaca before the Incans. Ruled by the high priest and sun king Con-Tiki, they built temples with huge stone slabs quarried on an opposite shore and ferried across the water on balsa rafts. Supposedly, a turf war had wiped out most of the white race. Con-Tiki and a few companions escaped down the coast, eventually rafting westward across the ocean.

Heyerdahl hypothesized that Tiki and Kon-Tiki were one and the same, and the source of Pacific cultures was not Asia, as orthodox scholars held, but South America. It was no mere coincidence, he said, that the huge stone figures of Tiki on this Polynesian island resembled the monoliths left by pre-Incan civilizations. His radical conclusion: The original inhabitants of Polynesia had crossed the Pacific on rafts, 900 years before Columbus traversed the Atlantic.

The scientific community dismissed Heyerdahl’s findings. Fellow academics claimed humans could never have survived the months of exposure and privations, and that no early American craft could have weathered the violence of the Pacific’s storms. When Heyerdahl failed to interest New York publishers in his manuscript, the evocatively titled “Polynesia and America: A Study of Prehistoric Relations,” he decided to test his theories of human migration by attempting the journey himself. He vowed that if he pulled it off, he’d write a popular book.

Heyerdahl’s father, the president of a brewery and a mineral water plant, wanted to bankroll the expedition. But his plans were scuttled by restrictions on sending Norwegian kroner out of the country. So the younger Heyerdahl used his considerable powers of persuasion to scrounge the money ($22,500). He then put out a call for crew members: “Am going to cross the Pacific on a wooden raft to support a theory that the South Sea islands were peopled from Peru. Will you come? Reply at once.’’

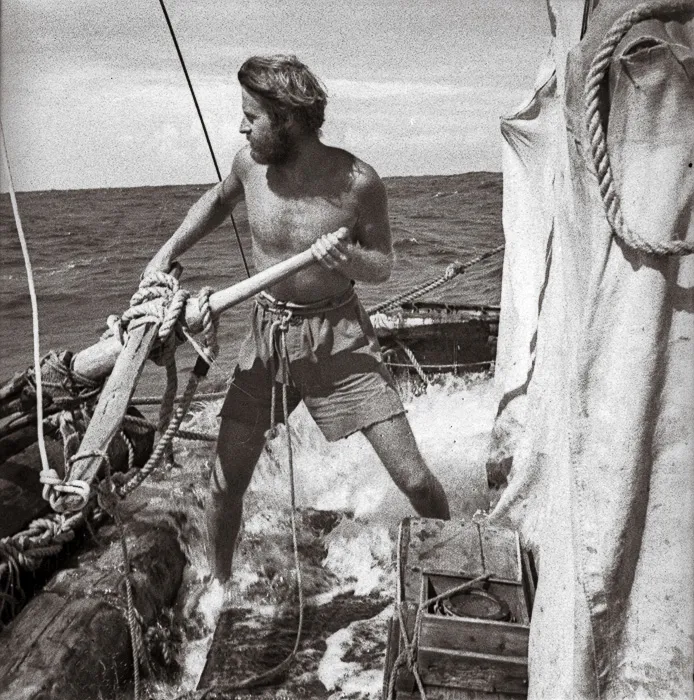

Four Norwegians and a Swede were game. Though the recruits knew Heyerdahl, they didn’t know one another. Most were intimate with danger as members of Norway’s wartime underground. They had either been spies or saboteurs; Heyerdahl himself had served as a paratrooper behind Nazi lines. Curiously, he could barely swim. Having twice almost drowned as a boy, he had grown up terrified of water.

Heyerdahl and countryman Herman Watzinger flew to Lima and, during the rainy season, crossed the Andes in a jeep. In the Ecuadorean jungle, they felled nine balsa trees and floated them downriver to the sea. Using ancient specs gleaned from explorers’ diaries and records, the crew patiently assembled a raft in the naval harbor of Callao.

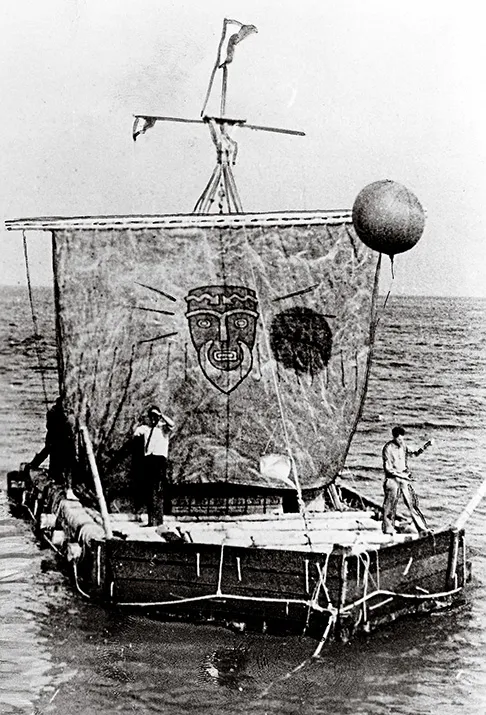

The Kon-Tiki ran against every canon of modern seamanship. Its base—made of balsa logs ranging in length from 30 to 45 feet—was lashed to crossbeams with strips of hand-woven Manila rope. On top was laid a deck of bamboo matting. The raft’s small half-open cabin of bamboo plaits and leathery banana leaves was too low to stand in. A bipod mast was carved of mangrove, hard as iron. The square sail, bearing a likeness of the sun god, was set on a yard of bamboo stems, bound together; the helm was a 15-foot-long mango wood steering oar. For verisimilitude, this weird vegetable vessel was constructed without spikes, nails or wire—all of which were unknown to pre-Columbian Peruvians.

Though ignorant of the Incan art of steering, Heyerdahl was well aware of the perils awaiting an open raft with no more stability than a cork. (Balsa is, in fact, less dense than cork.) Skeptics—including National Geographic magazine, which declined to sponsor the expedition—treated Heyerdahl like he was on a dice roll with death. So-called experts predicted that the balsa would quickly break under the strain; that the logs would wear through the ropes or get waterlogged and sink; that the sail and rigging would be stripped by sudden, screaming winds; that gales would swamp the raft and wash the crew overboard. A naval attaché bet all the whiskey the crew members could drink over the rest of their lives that they’d never make it to the South Seas alive.

Despite the warnings, the six men and their parrot, Lorita, put to sea on April 28, 1947. Drifting with the trade winds, riding heavy swells, the unwieldy Kon-Tiki proved astonishingly seaworthy. Rather than chafe the Manila rope lashings, the balsa logs became soft and spongy, leaving the rope unharmed and effectively protecting it. Water swept over the raft and through the logs as if passing through the prongs of a fork. The floating prefab progressed through the southern latitudes at an average rate of 37 nautical miles a day.

According to Heyerdahl’s account, when the seas were really rough and the waves really high—say, 25 feet—the helmsmen, sometimes waist deep in water, “left the steering to the ropes and jumped up and hung on to a bamboo pole from the cabin roof, while the masses of water thundered in over them from astern. Then they had to fling themselves at the oar again before the raft could turn around, for if the raft took the seas at an angle the waves could easily pour right into the bamboo cabin.”

Among the post-Incan furnishings provided by the U.S. military were tinned food, shark repellent and six-watt transmitters. “Heyerdahl knew the value of good marketing,” offers Reidar Solsvik, curator of the Kon-Tiki Museum in Oslo. “He only allowed one navigator in his crew, but he made sure his raft had five radio sets.” Heyerdahl’s radioman broadcast daily progress reports to ham operators, who relayed the messages to a press as ravenous as bird-eating sharks and a postwar public eager to embrace overnight heroes. “The general public was enthralled,” says Jeremy Thomas. “Much of western civilization lay in ruins, and the Kon-Tiki took all the hardship off the front pages.”

Newspapers around the world charted the path of the daredevil explorers as if they were orbiting the moon. “Heyerdahl was a great storyteller, but his true genius was in PR,” says Joachim Roenning, who directed the new film with his childhood friend Espen Sandberg. “The voyage of the Kon-Tiki was the world’s first reality show.”

Aboard the raft, the 20th-century Argonauts supplemented their G.I. rations with coconuts, sweet potatoes, pineapples (they had stashed away 657 cans), water stored in bamboo tubes and the fish they caught. During long lulls, they entertained themselves by baiting the ever-present sharks, snatching them by the tails and hoisting them aboard. Dozens of them. In the documentary assembled from footage Heyerdahl shot with his trusty 16-mm camera, a crew member dangles a mahi-mahi over the side of the raft and a shark pops up, snaps its jaws and takes half of the fish with it. “Just a childish game to relieve boredom,” says Heyerdahl’s eldest son, Thor Jr., a retired marine biologist. “For Norwegians, the concept of ‘conversation’ probably didn’t exist in those days.”

It would be three months before land was sighted. The Kon-Tiki passed several of the outlying islands of the Tuamotu Archipelago, and after 101 days at sea, was pushed by tail winds to a jagged coral reef. Rather than risk running the raft aground, Heyerdahl ordered the sail lowered and centerboards up. Anchors were rigged from the mast. A swell lifted the Kon-Tiki high and flung it in the shallows beyond the roaring breakers. The cabin and mast collapsed, but the men hung onto the main logs and emerged mostly unharmed. They straggled ashore on Raroia, an uninhabited atoll in French Polynesia. The flimsy Kon-Tiki had traveled more than 3,700 nautical miles.

Heyerdahl’s book would inspire a pop phenomenon. Kon-Tiki begat Tiki bars, Tiki motels, Tiki buses, Tiki sardines, Tiki shorts, Tiki cognac, Tiki chardonnay, vanilla-cream Tiki wafers and a tune by the Shadows that topped the British singles charts. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Enchanted Tiki Room, a Disneyland attraction that features Tiki drummers, Tiki totem poles and a flock of tropical Audio-Animatronic birds singing “The Tiki Tiki Tiki Room.”

Looming in the dim light, a colossal whale shark gambols in the briny deep. The 30-foot creature, a plastic model of one that darted playfully beneath the Kon-Tiki and threatened to upend it, is suspended from the basement ceiling of the museum. Many a kid who grew up in or visited Oslo has stood in the semidarkness and marveled at the monster and imagined its fearful snort. In the museum’s diorama, the ocean stretches on forever.

Joachim Roenning and Espen Sandberg first glimpsed the whale shark when they were 10 years old. But what really caught their eye was the shiny gold idol that reposed in a glass case one floor above: Heyerdahl’s Oscar. “For us,” says Sandberg, “that was even bigger than the whale shark.”

Growing up in Sandefjord, a small town south of Oslo, Sandberg and Roenning didn’t read and reread Kon-Tiki to learn about migration theory. “We wanted to be part of Heyerdahl’s adventure,” says Roenning. “As a Norwegian, he fascinated us. He was ambitious and unafraid to admit it, which is not very Norwegian.”

Heyerdahl never veered from the course he set. In the wake of the Kon-Tiki, he pursued and promoted his controversial theories. He led cruises aboard the reed rafts Ra, Ra II and Tigris. He conducted fieldwork in Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia and Canada. In Peru, he unearthed raft centerboards that he believed suggested return voyages from Polynesia against the wind might have been possible.

For a half-century, Heyerdahl refused to go to Hollywood. Many deep-pocketed producers came calling about Kon-Tiki. “All were kicked out to sea,” says Sandberg. “I think Thor was afraid of becoming the Kon-Tiki Man. He wanted to be judged on his body of work.”

Then one day in 1996 Jeremy Thomas showed up on the doorstep of Heyerdahl’s home in the Canary Islands. The British impresario had an Oscar under his belt—for Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor (1987)—and a story pitch on his lips. “In my imagination,” he says, “Kon-Tiki was about six hippies on a raft.”

When Heyerdahl, then 81, resisted, the 47-year-old Thomas persisted. He enlisted the aid of Heyerdahl’s third wife, Jacqueline, a former Miss France who’d appeared in a tranche of American movies (Pillow Talk, The Prize) and TV shows (“Mister Ed,” “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.”). On Thomas’ third trip to the Canaries, Heyerdahl caved and signed over the rights. It wasn’t necessarily that Thomas’ countercultural vision had won him over. “Thor was short on expedition funding for one of his wilder theories,” says Reidar Solsvik. Heyerdahl believed that the Viking god Odin may have been a real king in the first century B.C. He used at least some of the money to search in southern Russia for evidence of Odin, who ruled over Asgard.

Thomas sought funding, too. He hoped to mount Kon-Tiki as an English-language blockbuster with a $50 million budget. He sent a series of big-name screenwriters to confer with Heyerdahl, whose own script was rejected out of hand. Reportedly, Melissa Mathison of E.T.: The Extraterrestrial fame wrote a draft. Jacqueline remembers accompanying her husband to a screening of Raiders of the Lost Ark, which starred Mathison’s then husband, Harrison Ford. “Thor was not impressed by Indiana Jones,” Jacqueline says. “They had different approaches to archaeology.”

Who would play Heyerdahl? Lots of names were tossed around: Ralph Fiennes, Kevin Costner, Brad Pitt, Jude Law, Christian Bale, Leonardo DiCaprio and, Jacqueline’s personal favorite, Ewan McGregor. Basically, any big-name actor who could pass as a blond.

But even with Phillip Noyce (Patriot Games) aboard to direct, financing proved difficult. “Potential backers thought moviegoers wouldn’t be interested in the voyage because no one had died,” Thomas says. “You can’t make an adventure film about fishing and sunbathing.” The poor parrot Lorita would have to be sacrificed for art.

Before Heyerdahl’s death in 2002, Thomas reduced the movie’s scale and brought in Norwegian writer Petter Skavlan to reshape Kon-Tiki as a contemporary Norse tale. Noyce bowed out and was replaced by Roenning and Sandberg, whose 2008 World War II thriller Max Manus is Norway’s highest-grossing film ever.

Instead of filming on the high seas of Australia and Fiji, as Thomas had planned, the shooting location was moved to the Mediterranean island of Malta, where the costs were lower and the sea was flat. The budget shrunk to $15 million, petty cash by Hollywood standards. The Scandinavian cast did multiple takes in Norwegian and English. “I wanted more than 12 people to see the film,” Thomas said. In Norway, they already have: Kon-Tiki has already grossed some $14 million at the box office.

When discussing the movie, Thomas tends to sounds like a marketing guru who’s brought a dormant product back to life. “Celebrities like Marilyn Monroe and James Dean are still hot largely because they died young,” he says. “Heyerdahl got cold because he died very old. The new film will help invigorate his brand.”

Initially, the repackaging troubled Thor Jr. He objects to the depiction of crewmate Herman Watzinger. In real life, Watzinger was a plucky refrigeration engineer who resembled Gregory Peck. In the film, he’s a gutless, beer-gutted refrigerator salesman known to sharks as Lunch. “I regret that the filmmakers used Herman’s name,” says Thor Jr. “I understand why they needed a character who represented human weakness, but they should have called him Adam or Peter.”

Watzinger’s 70-year-old daughter, Trine, was not amused. Before the picture premiered last summer in Oslo, she complained to the Norwegian press. Accused of “character assassination,” the filmmakers tried to mollify Trine with the idea that Watzinger redeems himself at the end of the movie—his nifty scheme involving wave patterns propels the Kon-Tiki through the rollers. Still, she refused to attend the premiere. “A disclaimer has been inserted at the end of the DVD,” Thor Jr. says. “Of course, you have to sit through the closing credits to see it.”

His other concern was the aggressively romantic ending. On the beach in Raroia, a crewmate hands Thor Sr. a Dear Johan letter from Liv. In a voice-over, she selflessly explains why she’s dumping him: Unencumbered by family, he’ll be free to chase impossible dreams. The camera cuts from Liv—turning away from the sun and walking toward their house in the mountains of Norway—to Thor, squinting into the sun and toward the glowing sail of the Kon-Tiki.

***

As it turns out, reality was a bit more complex. “There was no letter,” reports Thor Jr. His mom, he says, never quite forgave his dad for squelching her possible dreams on their honeymoon in the Marquesas. Liv wanted to be seen as half of a research team, but Thor insisted on taking all the credit. “My father couldn’t cope with her being such a strong, independent woman,” says 74-year-old Thor Jr., who was estranged from his old man for much of his youth. “His idea of the perfect female was a Japanese geisha, and my mother was no geisha.”

A month after the Kon-Tiki made landfall, the Heyerdahls arranged to reunite at an airport in New York. He would fly from Tahiti; she, from Oslo. He was waiting on the tarmac when her plane landed. “She was eager to embrace him,” Thor Jr. says. But she could barely pierce the phalanx of photographers that encircled him.

Liv was furious. “She had been set up,” Thor Jr. says. “An intimate private meeting had become a public performance. She gave my father a very cold hug.” Thor Sr. felt humiliated. He and Liv divorced a year later.

Heyerdahl’s migration ideas haven’t fared much better than his first marriage. Though he enlarged our notions of the early mobility of humans, his Kon-Tiki theory has been widely discredited on linguistic and cultural grounds. He was partly vindicated in 2011 when Norwegian geneticist Erik Thorsby tested the genetic makeup of Polynesians whose ancestors had not interbred with Europeans and other outsiders. Thorsby determined that their genes include DNA that could have only come from Native Americans. On the other hand, he was emphatic that the island’s first settlers came from Asia.

“Heyerdahl was wrong,” he said, “but not completely.”