Jewel of the Jungle

Traveling through Cambodia, our writer details the history and archaeology of Angkor’s ancient temples

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/angkor_388.jpg)

Just before sunrise on a cloudy May morning in northern Cambodia, I joined hundreds of tourists crossing the wide moat to the outer wall of Angkor Wat, often said to be the largest religious structure in the world. Inside the rectangular courtyard, which covers more ground than 200 football fields, I waited near a small lake in front of the temple. Within minutes the sun appeared behind its five iconic towers, each shaped as a closed lotus bud, representing the five peaks of Mount Meru, home of the gods and the mythical Hindu center of the universe.

The temple's precise, symmetrical beauty was unmistakable. The other tourists all faced the sun, watching in stillness and whispering in foreign tongues, as hundreds more arrived behind them. Angkor Wat at sunrise is a wondrous spectacle, one that I would return to several times during my stay in Cambodia.

I had come to the temples of Angkor prepared, having read about their archaeology and history and learned of their immense size and intricate detail. The mystery of why an early Khmer civilization chose to abandon the temples in the mid-15th century, after building them during a period of more than 500 years, intrigued me. So too did the tales of travelers who "discovered" Angkor in the centuries that followed, some of whom thought they had stumbled across a lost city founded by Alexander the Great or the Roman Empire—until finally, in the 1860s, the French explorer Henri Mouhot reintroduced the temples to the world with his ink drawings and the postmortem publication of his journal, Travels in Siam, Cambodia, and Laos.

But on that first morning I realized that such knowledge was unnecessary to appreciate this remarkable achievement of architecture and human ambition. "There are few places in the world where one feels proud to be a member of the human race, and one of these is certainly Angkor," wrote the late Italian author Tiziano Terzani. "There is no need to know that for the builders every detail had a particular meaning. One does not need to be a Buddhist or a Hindu to understand. You need only let yourself go..."

****

Although Angkor Wat is the largest and best known of these temples, it is but one of hundreds built by the kingdom of Angkor. Huge stone monuments scattered across hundreds of square miles of forest in northern Cambodia, the temples are the remains of a vast complex of deserted cities—which included manmade lakes, canals and bridges—that were astonishing in their size and artistic merit.

But piecing together information about the ancient Khmers who built them has not been easy for archaeologists and historians. The only written records that still exist are the inscriptions on the temple walls and the diary of a Chinese diplomat who visited Angkor in 1296. All administrative buildings and the homes of kings and commoners alike were made of wood; none have survived, leaving only the religious creations of brick and stone.

Direct ancestors of modern-day Cambodians, the Khmers are thought to have descended from the Funan peoples of the Mekong delta. Funan was a decentralized state of rival kings that thrived as a trading link connecting China and the West for the first few centuries A.D. In the late sixth century, Funan was superseded by the state of Chenla, based farther north into Cambodia's interior. Chenla lasted for about 250 years until the start of the Angkor period.

Meanwhile, Hindu and Buddhist influences, which originated in centuries-old contact with Indian traders, appeared in the region. (Neither ever fully displaced the local animist religion, but rather assimilated into it.) Elite Khmer rulers commissioned the building of temples and gave themselves Sanskrit names to demonstrate their wealth and power. Their subjects made donations to the temples to curry favor—both with the gods and with the local ruler. Temples, as such, were not only religious but also commercial centers. In the time of Angkor many temples operated as small cities, and some of them as very large cities.

Around A.D. 800 a powerful regional king named Jayavarman II consolidated the rival chiefdoms in Cambodia and founded the kingdom of Angkor. It was Jayavarman II who instituted the cult of the Devaraja (literally "god-king" or "king of the gods"), symbolically linking Khmer royalty to the divine realm.

For the next six centuries, Angkor's heartland was the area between the northern banks of the Tonle Sap lake and the Kulen hills to the north. Here the temples are most concentrated, though Angkorian constructions exist all throughout Southeast Asia.

Life in Angkor was busy, ritualistic, unstable. Wars against neighboring armies from Thailand and Champa (modern-day central Vietnam) were constant. A vaguely defined process for royal succession left the throne frequently exposed to ambitious usurpers. For the common rice-grower and peasant, the feverish pace of temple-building required labor, money in the form of taxes and the prospect of being drafted into war by the king.

Three hundred years after the beginnings of the kingdom, King Suryavarman II ordered the construction of Angkor Wat as a shrine to the god Vishnu. Fittingly for the king who erected this most sublime of the Angkor temples, Suryavarman II ruled at the height of Angkor's dominion over Southeast Asia. During his reign from 1113 to 1150, Angkor's control extended beyond Cambodia to parts of modern-day Thailand, Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam.

The other great king of Angkor was Jayavarman VII, who in 1181 assumed the throne after driving out an occupying army from Champa. He initiated an intensive building program of temples, roads and hospitals that, according to some estimates, created twice as many monuments as Angkor already had.

Jayavarman VII's greatest project was the temple city of Angkor Thom, enclosed by a square wall more than seven miles long and about 26 feet high. In its precise center is the Bayon, a mysterious, oddly shaped temple with 54 towers. Carved into each of the towers' four sides is a serene, enigmatic face, possibly a composite of a bodhisattva and Jayavarman VII himself. After his death in 1219 the kingdom began a slow decline.

The Khmers moved south to Phnom Penh sometime after 1431, the last year that Thai armies invaded Angkor and made off with much of its treasure and women. Scholars and archaeologists still ponder why they left. Some say the Khmers sought a more secure capital from which to defend against the Thais. Others believe the Khmers wished to engage in further trade with China, which could be more easily conducted from Phnom Penh, an intersection of four rivers, including the Mekong. No single reason is certain.

Although Angkor was mostly abandoned, it was never completely forgotten. Some ascetic monks stayed behind, and for a brief time in the 16th century the Khmer kings returned the capital to Angkor, only to leave once again. Missionaries and pilgrims occasionally came upon the neglected temples, which through the centuries were swallowed by the jungle.

After Mouhot's "rediscovery" and the French colonization of Cambodia in the 1860s, extensive restoration work on the temples was begun by the École Française d'Extrême-Orient (the French School of the Far East). Today more work continues to be done by Unesco and organizations from Cambodia and many other countries. Over the years, the restoration process has faced many difficulties. Statues, artwork and even sections of the temples themselves have been vandalized or stolen. The murderous Khmer Rouge government under Pol Pot halted the restoration work completely when it occupied the temples as a military stronghold in the late 1970s.

Perhaps the most serious threat to the temples in recent years is one brought on by their own appeal: tourism. After a half-century of political instability, war and famine, Cambodia became safe for tourism about a decade ago. Angkor is the engine now driving this thriving industry, which last year brought 1.7 million visitors to the country, 20 percent more than the previous year, according to the Cambodian Tourism Ministry. Other estimates put the number even higher, and it is projected to continue growing.

This attraction presents a dilemma. The government remains plagued by corruption, and the average Cambodian income is the equivalent of one American dollar per day. The tourism generated by Angkor is therefore a vital source of income. But it also poses a serious threat to the structural integrity of the temples. In addition to the erosion caused by constant contact with tourists, the expansion of new hotels and resorts in the nearby town of Siem Reap is reportedly sucking dry the groundwater beneath the temples, weakening their foundations and threatening to sink some of them into the earth.

****

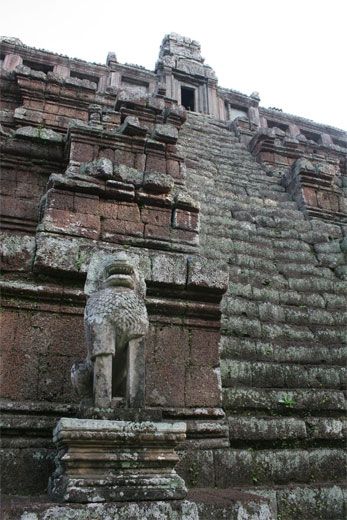

During my visit I walked the temples' dark corridors, climbed their precipitous steps and studied up close the finely carved bas-reliefs, where pictorial legends of Hindu and Buddhist mythology and the exaggerated exploits of Khmer kings are engraved on their walls. Usually around noon, when most tourists seemed to escape the sweltering heat to have lunch, I was able to find an empty, contemplative space once inhabited by the gods.

As I took in the vast temples, I had to remind myself that the daily life of the early Khmers was violent and exacting. In their careful adherence to routines and rituals, could they have imagined how their efforts would one day be so revered? How different their experience must have been from the feelings of wonderment and awe now inspired by their temples, or by watching a sunrise at Angkor Wat.

Cardiff de Alejo Garcia, a freelance writer in Southeast Asia, has written about Muay Thai fighting for Smithsonian.com.