James W. Rouse’s Legacy of Better Living Through Design

There are still lessons to be learned from the visionary businessman who built a city

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/d8/76d8eefe-ec12-4c3b-b8b9-6798f831aca6/james-rousejpg800x0_q85_crop.jpg)

This week marks what would have been the 100th birthday of the late James W. Rouse (1914-1996), an ambitious businessman, a crusading activist, an early proponent of urban renewal, and a developer who is often credited with inventing the shopping mall. Oh, and he also built a city.

Rouse grew up in Easton, Maryland, the son of hard-working parents of mercurial fortunes who instilled in him a tireless work ethic. He worked his way through law school, then as a clerk for the fledgling Federal Housing Administration, then as a banker, then as partner in his own mortgage banking firm, the Moss-Rouse Company, later the James W. Rouse & Company Inc. Some time along the way, the self-made millionaire developed a passion for the American city. In the late 1940s, he became involved with rehabilitating (not bulldozing) Baltimore slums, eventually serving on the President's Advisory Committee on Government Housing Policies and Programs where he helped develop the nascent concept of urban renewal - a word that once had more optimistic connotations. Throughout his entire career, Rouse walked a line between pragmatics and poetics. Rather than being driven by visions of profits and the bottom line, he truly wanted to create better places for people--all people--to live.

Some time after his mortgage firm began financing large commercial properties, Rouse decided to try developing his own shopping center - with a twist that would change the way we shop forever. In 1958, he built Harundale Mall in Glen Burnie, Maryland. Harundale was actually the second enclosed shopping center in the United States (the first opened a few months earlier in Minneapolis), but it’s credited with inspiring the proliferation of the modern mall concept. It was an expensive, risky undertaking but it paid off. Not only did the fully climate-controlled shopping center prove convenient for shoppers and lucrative for retailers, it had the unexpected side effect of becoming a community center where people--not just teenagers--began to gather like it was a town square. Rouse encouraged this behavior by building fountains, libraries, post offices, and even churches into his malls. Though some attribute the shopping mall to the decline of the American downtown, Rouse’s ambition was actually to give the placeless suburbs a civic anchor. He continued to develop malls and marketplaces, but the next step seemed obvious to the visionary developer. James Rouse rolled up his sleeves and built a city.

He believed that we demanded too little of ourselves and our cities. He believed that the city could be better, that we could be better. Rouse believed that cities are just too big and their impossible scale alienates us from one another, fostering an apathy and loneliness. In Rouse’s view, we're at our best in smaller communities where there is a sense of responsibility to one's city and to one's neighbor. He imagined a beautiful, self-sustaining American City--a new America, really--that fostered economic, racial, and cultural harmony. The name of this new city on a hill: Columbia.

The story of Columbia starts in 1962, when several mysterious organizations began quietly buying thousands of acres in rural Howard County, Maryland, between Baltimore and Washington, D.C. Rumors spread through the region: the government was building a massive compost pile; no, a missile silo; that’s not it, Volkswagen was building a factory. It was all Rouse, of course, working through several shell corporations and various banks to quickly buy more than 15,000 bucolic acres of farmland and gentle hills populated by poplars, oaks and pines. The secrecy was necessary to keep farmers from raising their prices too high, and it went beyond the acquisition stage. Maps and contracts related to his endeavor were kept in a locked room, codenamed “Shangri-La” by the three people who had keys and knew the full extent of Rouse’s vision. Full of double-blinds, misdirections, and suspicious enemy agents, the elaborate $23 million shell game was executed like an CIA op and would make a great caper film.

Ultimately, by hook, crook, and pocketbook, Rouse succeeded in acquiring his land and on October 29, 1963, he publicly revealed himself as the buyer, informing the Howard County commissioners that he proposed to develop the land into a "balanced, planned community" that would "fit naturally into the Howard County landscape, preserving the stream valleys, protecting hills and forests, and providing parks and greenbelts." People were surprised but surprisingly not upset. Balding, bespectacled, and usually dressed in a casual sportcoat, Rouse cut an unimposing figure but had an evangelical passion for his work and inspired support with incredibly eloquent speeches about the problems of American suburbs and his plan to reimagine the city:

"Our cities grow by sheer chance--by accident….A farm is sold and begins raising houses instead of potatoes--then another farm. Forests are cut; valleys are filled; streams are buried in storm sewers....Thus, bits and pieces of a city are splattered across the landscape. By this irrational process, noncommunities are born--formless places without order, beauty or reason, places with no visible respect for people or the land. Thousands of small, separate decisions made with little or no relationship to one another, nor to their composite impact, produce a major decision about the future of our cities and our civilization--a decision we have come to label 'suburban sprawl.' What nonsense this is! What reckless, irresponsible dissipation of nature's endowment and of man's hope for dignity, beauty, growth!

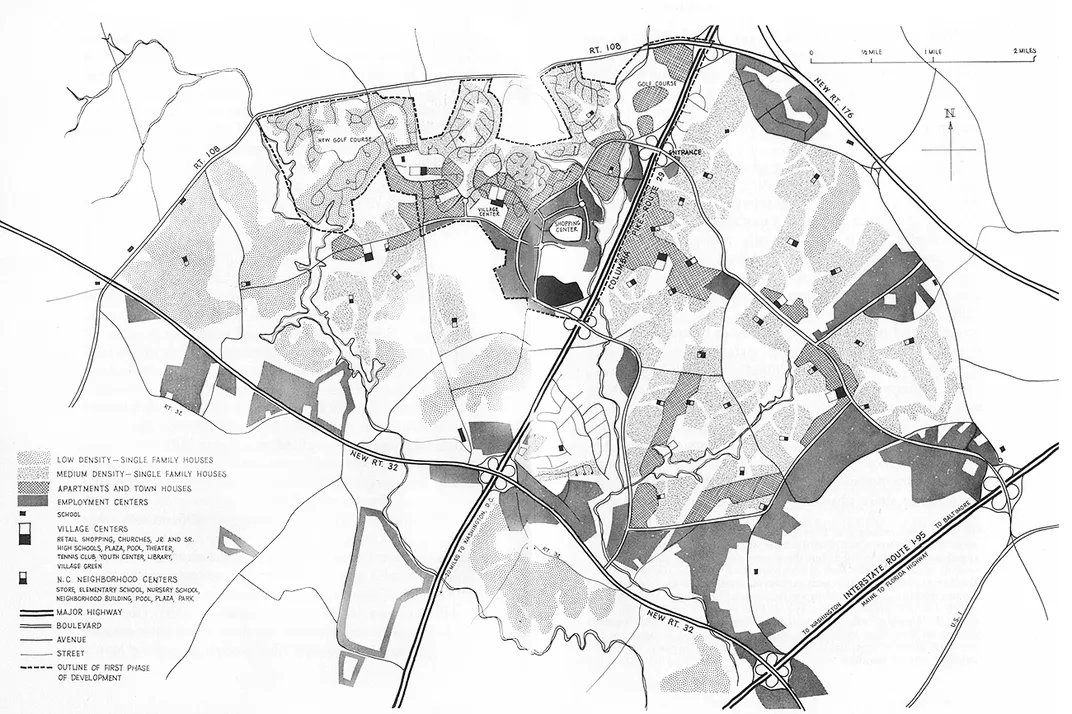

Columbia would be different; it would be, as Rouse said, a “garden for the growing of people.” In building a city for 100,000 people, he had four main goals: 1) to create a fully self-sustaining city, not just a better suburb, where residents would both live and work, 2) to respect the land, 3) to produce the most accommodating environment for the growth of people, and 4) to make a profit. Rouse made it clear that profit was not an added benefit of the plan, it was a primary objective. It was an unimaginably ambitious undertaking for the time, but who else would try? Rouse believed that only a corporation had the infrastructure, resources, and influence to successfully create an entirely new city.

To achieve these goals, Rouse didn’t just hire a team of talented planners and designers, but also scholars, government officials, and sociologists. This “Work Group,” as the men and women were known, masterminded the true innovation at Columbia: the development of social planning alongside urban planning. They studied American cities, religious practices, and social behavior to create new integration strategies, public transport options, and more efficient urban design. The Work Group devised Columbia’s hierarchical plan made up distinct neighborhoods gathered into nine different villages, which were clustered around a single “downtown” core. Each village had its own schools, libraries, hospitals, and other civic institutions. The small villages were not only developed to accommodate the natural terrain, but also to cultivate a sense of social responsibility among its residents. At a time when racial tensions were running high, Columbia was Rouse's ideal vision of the country’s future: a culturally diverse, integrated city where kids walked to school and the office was just a quick bus ride away. Rouse promised that every single person who works in Columbia could afford to live there. To that end, Rouse and his compatriots fought to ensure that subsidized housing and apartments were built alongside larger single-family homes.

Despite this unique sociological approach, Columbia was decidedly traditional looking, even downright dowdy in some parts. It wasn’t that Rouse didn’t care about good design - quite the opposite, in fact. Quality was of the utmost importance to him and in almost all his projects he had a hand in picking everything from the landscaping to the garbage cans. Though initially a proponent of modernist architecture, Rouse’s experience with malls taught him that innovative architecture is not good for business. In the early 1960s, the American public wasn’t quite ready to embrace a modernist city and Columbia was about giving people what they wanted. For Rouse, the key to success was high-quality traditional design.

As he told students during a lecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design: “We must keep in focus what architects and developers have let slide from view: the only real justification of any one of these centers is to serve the people in the area: not the merchants, not the architects, not the developers. If we find what works best for people, we will wind up with both good design and high profits." Columbia may be dotted with ranch burgers and colonial homes but for his own company headquarters, a flat-roofed modernist structure on man-made Lake Kittamaqundi, Rouse took a chance on a young architect named Frank Gehry. It was one of the earliest commissions for Gehry, who would of course go on to become one of the most influential architects of the last 50 years.

Columbia opened on June 21, 1967. It wasn’t finished, but it was ready. The new city had no problem attracting a diverse cross-section of residents and industries, and it quickly surpassed its development and cultural goals. It seemed, for a time at least, to have achieved its purpose, which was “the only valid ultimate purpose of any civilization,” according to Rouse: “ to grow better people; more creative, more productive, more inspired, more loving people."

Even after his retirement in 1979, Rouse continued this mission, founding the Enterprise Foundation (now Enterprise Community Partners), which supports affordable housing and social services in lower-income neighborhoods.

In the decades since it opened Columbia has, like any city, had its struggles. Residents have complained about high taxes, dense traffic, and crime. But Columbia consistently ranks on lists of the best places to live in America and the city is still growing. In 2010, the County Council approved the Downtown Columbia Plan to attract new business, new residents, and rejuvenate the central core of the city. Frank Gehry’s old building will soon reopen as a Whole Foods - and there’s talk that Gehry might build again in Columbia. Of course, Columbia has its critics, some of whom say it never became the city it was meant to be, that it’s just another cookie-cutter suburb and Rouse’s dream of economic and racial equality was just that - a dream; or worse, a lie. But, as author Michael Chabon writes in an essay about growing up in Columbia, “just because you have stopped believing in something you once were promised does not mean that the promise itself was a lie.”

When Rouse began his great undertaking, cities were dying as residents fled to the suburbs. Today, the opposite is true. But if rents continue to rise and cities become enclaves for the wealthy, perhaps new models will emerge, or old models will be revisited. Whatever comes to pass, the following speech from James Rouse, a call to arms first spoken in 1967, still rings true today:

“We are living in the midst of what history may find to have been the most important revolution in the history of man. It is the upheaval which has lifted to new heights man's respect for the dignity and importance of his fellow man….This revolution is barely under way. The tools for carrying it out have been forged over the past several decades. We are now developing the will to pick up the tools and put them to work. Over the next ten years, we will see an urban revolution that will lead all men...to take possession of their cities and make them work for people who live there.”

Note: various Rouse quotes excerpted from the book Columbia and the New Cities.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)