How Trees Defined America

Historian Erik Rutkow argues in a new book that forests are key to understanding how our nation developed and who we are today

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/american-canopy-rutkow-treestump-631.jpg)

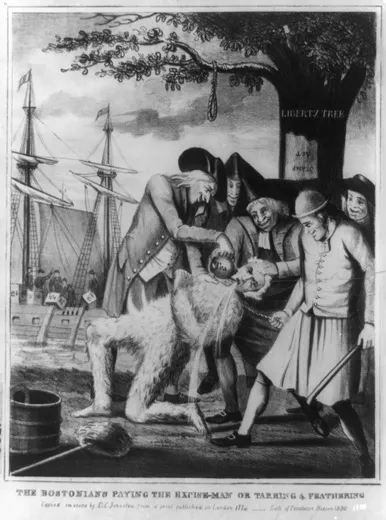

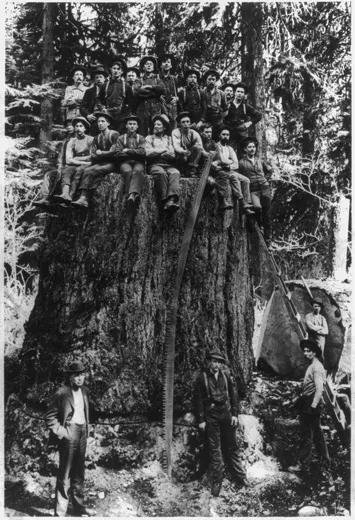

According to historian Eric Rutkow, the United States would not be the country we know today without the vast forests that provided the growing nation with timber, paper and other resources—and eventually inspired our environmental consciousness. In his recently published book American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation, Rutkow traces the history of the United States through our trees, from the mighty elm in the heart of Boston that would become the Liberty Tree, to California’s giant conifers, which inspired an early generation of conservationists.

How has Americans’ relationship with trees shaped our character?

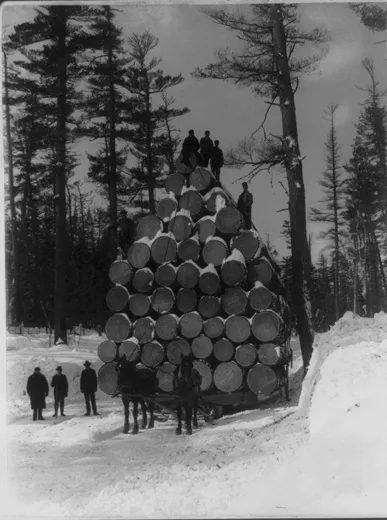

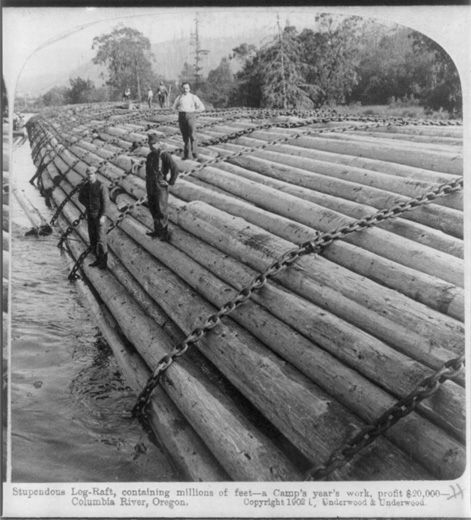

We have such a material abundance of trees. Trees allowed us to develop this style of aggressive consumption, and this style of immediacy over permanence in how we look at developing the landscape.

How has this relationship shifted over time?

For most of American history, trees surround us conspicuously. I’m not talking forests and the environment we plant around them, but our homes—you can really see that wood is everywhere. And there’s a shift that happens in the middle of the 20th century, where we’re still depending on wood to build many things, but we start hiding it and processing it. At the same time we start pursuing new legislation to create things like wilderness areas, and to have recreation in forests and national parks. That split is a really interesting development in the American character, the evolution of the idea of the forest as where we go to find spirituality, the forest as where we go to find recreation, the forest as where we go to escape.

With wood and forests less visible in our daily lives, have we lost touch with our trees?

In some ways we’ve lost an obvious closeness to our trees. If you were to look back at earlier epochs, many Americans would be able to at least identify the trees that constitute the environment where they lived. We’ve really lost that sensibility. If you were to read this book and simultaneously read a few books on tree identification, I think you would then be able to walk through whatever environment you’re in—it could be a suburb, it could be a city, it could be the countryside, it could be a park—and you would not only be able to name those trees, but, seeing how they were through the history of America, you could really start to see the history of how the country evolved.

Over the course of your research, what were some of the most interesting things you learned?

There’s a surprisingly high correlation between the presidents I think of as great and the presidents that were considered tree-lovers. George Washington was obsessed with trees. Thomas Jefferson was a very informed horticulturalist and had a lot of books on trees and planted a lot of tree species. The president who created the greatest number of national forests was Teddy Roosevelt. He was profoundly shaped by his ideas about wilderness and nature and forests. And very few people appreciate that FDR’s love for trees was very deep. When FDR was the president and he went to cast his vote—at that time they asked you to list your occupation—he wrote his occupation down as “tree grower.”

Much of the book deals with the destruction of forests and the gradual rise of Americans’ environmental consciousness. Is the goal to get readers to think about conservation?

I don’t think the book should necessarily be read as a polemic. The real takeaway is that it’s very hard to understand the American experience if you don’t understand our relationship to trees. This book is about understanding who we are and how we got there.

What could be done to boost consciousness about deforestation?

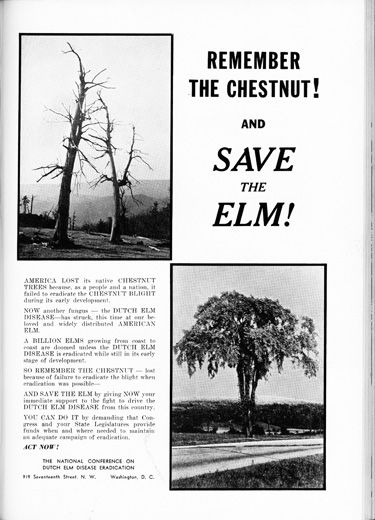

There’s a sensibility among a lot of people that many of the issues concerning our forests and how we use trees have largely been settled. These are things that are now taken care of by the government, by corporations, by the environmental movement. But there are plenty of active and unfolding issues, and it’s always worth being active and lending your voice. Certainly in the last 20 years, we’ve seen an increase in wildfires and the loss of trees to disease, and this trend is something that would really benefit from more civic engagement.

Does history suggest there’s hope for American forests?

There was a time in the United States that we were chopping down trees and planting almost no trees to replace them. We were net-losing trees every year. And that trend transformed over the course of the 19th century such that now there are more trees planted than being cut down. That’s a bright spot we have made progress in.

What might American forests look like in the future?

If the trends linked to global warming continue, we may see trees slowly migrating northward, while some species living at the edges of ecosystems, like the bristlecone pine, might go extinct. New advances in genetics, if applied, will raise ethical questions about the introduction of modified trees that might crossbreed in the wild. Given all of this, Americans in the future may someday wander through forests types that don’t yet exist. And they may struggle to find remnants of certain types of forests that we now think of as common.

Now that you know so much about trees and the history of forests, has that knowledge changed how you relate to trees and forests in your daily life?

Oh, absolutely. Five or ten years ago, I don’t think I could have identified many trees. I could probably have identified an oak tree and a maple tree by their leaves, and I knew that acorns were associated with oak trees, but I didn’t know much more than that. But once you start looking at trees in the landscape, once you start to see it this way, you really can’t un-see it. I find myself walking through New Haven or New York City and constantly asking questions: if I recognize the tree, how did it get there and why, and what can we say about what was happening in America at the time the tree was planted? So it’s gotten a little bit annoying, I suppose, with some of my friends. I have a hard time walking from A to B without stopping and pondering trees.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)