When Dolley Madison Took Command of the White House

It is thanks to the first lady that the famous Stuart painting of George Washington survived the British army’s invasion of D.C. in August 1814

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Dolley-Madison-directing-rescue-of-George-Washington-portrait-631.jpg)

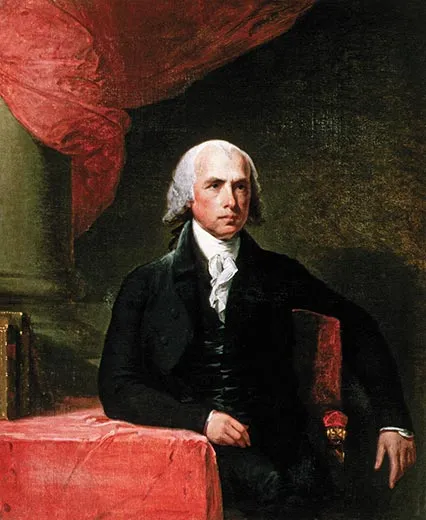

In the years leading up to America’s second war with Britain, President James Madison had been unable to stop his penny-pinching secretary of the treasury, Albert Gallatin, from blocking Congressional resolutions to expand the country’s armed forces. The United States had begun the conflict on June 18, 1812, with no Army worth mentioning and a Navy consisting of a handful of frigates and a fleet of gunboats, most armed with a single cannon. In 1811, Congress had voted to abolish Alexander Hamilton’s Bank of the United States, making it nearly impossible for the government to raise money. Worst of all, the British and their European allies had engaged (and would ultimately defeat) Napoleon’s France in battles across Europe in 1812 and 1813, which meant the United States would have to fight the world’s most formidable army and navy alone.

In March 1813, Gallatin told the president, “We have hardly money enough to last till the end of the month.” Along the Canadian border, American armies stumbled into ruinous defeats. A huge British naval squadron blockaded the American coast. In Congress, New Englanders sneered at “Mr. Madison’s War,” and the governor of Massachusetts refused to allow any of the state’s militiamen to join the campaign in Canada. Madison fell ill with malaria and the aged vice president, Elbridge Gerry, grew so feeble that Congress began arguing about who would become president if both men died. The only good news came from victories over lone British warships by the tiny American Navy.

Dolley Madison’s White House was one of the few places in the nation where hope and determination continued to flourish. Although she was born a Quaker, Dolley saw herself as a fighter. “I have always been an advocate for fighting when assailed,” she wrote to her cousin, Edward Coles, in a May 1813 letter discussing the possibility of a British attack on the city. Spirits had risen when news of an American victory over the British frigate Macedonian, off the Canary Islands, reached the capital during a ball given in December 1812 to celebrate Congress’ decision to enlarge the Navy at last. When a young lieutenant arrived at the ball carrying the flag of the defeated ship, senior naval officers paraded it around the floor, then laid it at Dolley’s feet.

At social events, Dolley strived, in the words of one observer, “to destroy rancorous feelings, then so bitter between Federalists and Republicans.” Members of Congress, weary of flinging curses at each other during the day, seemed to relax in her presence and were even willing to discuss compromise and conciliation. Almost all their wives and daughters were Dolley’s allies. By day Dolley was a tireless visitor, leaving her calling cards all over the city. Before the war, most of her parties attracted about 300 people. Now attendance climbed to 500, and young people began calling them “squeezes.”

Dolley undoubtedly felt the stress of presiding over these crowded rooms. “My head is dizzy!” she confessed to a friend. But she maintained what an observer called her “remorseless equanimity,” even when news was bad, as it often was. Critics heaped scorn on the president, calling him “Little Jemmy” and reviving the smear that he was impotent, underscoring the battlefield defeats over which he had presided. But Dolley seemed immune to such slander. And if the president looked as if he had one foot in the grave, Dolley bloomed. More and more people began bestowing a new title on her: first lady, the first wife of a U.S. president to be so designated. Dolley had created a semipublic office as well as a unique role for herself and those who would follow her in the White House.

She had long since moved beyond the diffidence with which she had broached politics in her letters to her husband nearly a decade before, and both had jettisoned any idea that a woman should not think about so thorny a subject. In the first summer of his presidency in 1809, Madison had been forced to rush back to Washington from a vacation at Montpelier, his Virginia estate, leaving Dolley behind. In a note he wrote to her after returning to the White House, he said he intended to bring her up to date on intelligence just received from France. And he sent her the morning newspaper, which had a story on the subject. In a letter two days later, he discussed a recent speech by the British prime minister; clearly, Dolley had become the president’s political partner.

The British had been relentless in their determination to reduce Americans to obedient colonists once more. Checked by an American naval victory on Lake Erie on September 10, 1813, and the defeat of their Indian allies in the West, almost a month later, the British concentrated their assault on the coastline from Florida to Delaware Bay. Again and again their landing parties swarmed ashore to pillage homes, rape women, and burn public and private property. The commander of these operations was Sir George Cockburn, a strutting, red-faced rear admiral, widely considered to be as arrogant as he was ruthless.

Even as many Washington residents began packing up families and furniture, Dolley, in correspondence at the time, continued to insist that no British Army could get within 20 miles of the city. But the drumbeat of news about earlier landings—British troops had sacked Havre de Grace, Maryland, on May 4, 1813, and tried to take Craney Island, near Norfolk, Virginia, in June of that year—intensified criticism of the president. Some claimed that Dolley herself was planning to flee Washington; if Madison attempted to abandon the city as well, critics threatened, the president and the city would “fall” together. Dolley wrote in a letter to a friend: “I am not the least alarmed at these things but entirely disgusted & determined to stay with him.”

On August 17, 1814, a large British fleet dropped anchor at the mouth of the Patuxent River, only 35 miles from the nation’s capital. Aboard were 4,000 veteran troops under the command of a tough professional soldier, Maj. Gen. Robert Ross. They soon came ashore in Maryland without a shot being fired and began a slow, cautious advance on Washington. There was not a single trained American soldier in the vicinity to oppose them. All President Madison could do was call out thousands of militia. The commander of these jittery amateurs was Brig. Gen. William Winder, whom Madison had appointed largely because his uncle, the governor of Maryland, had already raised a sizable state militia.

Winder’s incompetence became obvious, and more and more of Dolley’s friends urged her to flee the city. By now thousands of Washingtonians were crowding the roads. But Dolley, whose determination to stay with her husband was unwavering, remained. She welcomed Madison’s decision to station 100 militiamen under the command of a regular Army colonel on the White House lawn. Not only was it a gesture of protection on his part, it was also a declaration that he and Dolley intended to stand their ground. The president then decided to join the 6,000 militiamen who were marching to confront the British in Maryland. Dolley was sure his presence would stiffen their resolve.

After the president had ridden off, Dolley decided to show her own resolve by throwing a dinner party, on August 23. But after The National Intelligencer newspaper reported that the British had received 6,000 reinforcements, not a single invitee accepted her invitation. Dolley took to going up to the White House roof to scan the horizon with a spyglass, hoping to see evidence of an American victory. Meanwhile, Madison sent her two scribbled messages, written in quick succession on August 23. The first assured her that the British would easily be defeated; the second warned her to be ready to flee on a moment’s notice.

Her husband had urged her, if the worst happened, to save the cabinet papers and every public document she could cram into her carriage. Late in the afternoon of August 23, Dolley began a letter to her sister Lucy, describing her situation. “My friends and acquaintances are all gone,” she wrote. The army colonel and his 100-man guard had also fled. But, she declared, “I am determined not to go myself until I see Mr. Madison safe.” She wanted to be at his side “as I hear of much hostility toward him...disaffection stalks around us.” She felt her presence might deter enemies ready to harm the president.

At dawn the next day, after a mostly sleepless night, Dolley was back on the White House roof with her spyglass. Resuming her letter to Lucy at midday, she wrote that she had spent the morning “turning my spy glass in every direction and watching with unwearied anxiety, hoping to discern the approach of my dear husband and his friends.” Instead, all she saw was “groups of military wandering in all directions, as if there were a lack of arms, or of spirit to fight for their own firesides!” She was witnessing the disintegration of the army that was supposed to confront the British at nearby Bladensburg, Maryland.

Although the boom of cannon was within earshot of the White House, the battle—five or so miles away at Bladensburg—remained beyond the range of Dolley’s spyglass, sparing her the sight of American militiamen fleeing the charging British infantry. President Madison retreated toward Washington, along with General Winder. At the White House, Dolley had packed a wagon with the red silk velvet draperies of the Oval Room, the silver service and the blue and gold Lowestoft china she had purchased for the state dining room.

Resuming her letter to Lucy on that afternoon of the 24th, Dolley wrote: “Will you believe it, my sister? We have had a battle or skirmish...and I am still here within sound of the cannon!” Gamely, she ordered the table set for a dinner for the president and his staff, and insisted that the cook and his assistant begin preparing it. “Two messengers covered with dust” arrived from the battlefield, urging her to flee. Still she refused, determined to wait for her husband. She ordered the dinner to be served. She told the servants that if she were a man, she would post a cannon in every window of the White House and fight to the bitter end.

The arrival of Maj. Charles Carroll, a close friend, finally changed Dolley’s mind. When he told her it was time to go, she glumly acquiesced. As they prepared to leave, according to John Pierre Sioussat, the Madison White House steward, Dolley noticed the Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington in the state dining room. She could not abandon it to the enemy, she told Carroll, to be mocked and desecrated. As he looked anxiously on, Dolley ordered servants to take down the painting, which was screwed to the wall. Informed they lacked the proper tools, Dolley told the servants to break the frame. (The president’s enslaved White House footman, Paul Jennings, later produced a vivid account of these events; see sidebar, p. 55.) About this time, two more friends—Jacob Barker, a wealthy ship owner, and Robert G. L. De Peyster—arrived at the White House to offer whatever help might be needed. Dolley would entrust the painting to the two men, saying they must conceal it from the British at all costs; they would transport the portrait to safety in a wagon. Meanwhile, with remarkable self-possession, she completed her letter to Lucy: “And now, dear sister, I must leave this house...where I shall be tomorrow, I cannot tell!”

As Dolley headed for the door, according to an account she gave to her grandniece, Lucia B. Cutts, she spotted a copy of the Declaration of Independence in a display case; she put it into one of her suitcases. As Dolley and Carroll reached the front door, one of the president’s servants, a free African-American named Jim Smith, arrived from the battlefield on a horse covered in sweat. “Clear out! Clear out,” he shouted. The British were only a few miles away. Dolley and Carroll climbed into her carriage and were driven away to take refuge at his comfortable family mansion, Belle Vue, in nearby Georgetown.

The British arrived in the nation’s capital a few hours later, as darkness fell. Admiral Cockburn and General Ross issued orders to burn the Capitol and the Library of Congress, then headed to the White House. According to Lt. James Scott, Cockburn’s aide-de-camp, they found the dinner Dolley had ordered still on the table in the dining room. “Several kinds of wine in handsome cut glass decanters sat on the sideboard,” Scott would later recall. The officers sampled some of the dishes and drank a toast to “Jemmy’s health.”

Soldiers roamed the house, grabbing souvenirs. According to historian Anthony Pitch, in The Burning of Washington, one man strutted around with one of President Madison’s hats on his bayonet, boasting that he would parade it through the streets of London if they failed to capture “the little president.”

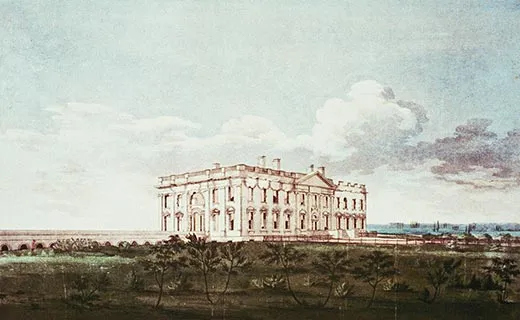

Under Cockburn’s direction, 150 men smashed windows and piled White House furniture in the center of the various rooms. Outside, 50 of the marauders carrying poles with oil-soaked rags on the ends surrounded the house. At a signal from the admiral, men with torches ignited the rags, and the flaming poles were flung through the smashed windows like fiery spears. Within minutes, a huge conflagration soared into the night sky. Not far away, the Americans had set the Navy Yard on fire, destroying ships and warehouses full of ammunition and other materiel. For a time, it looked as if all Washington were ablaze.

The next day, the British continued their depredations, burning the Treasury, the State and War departments and other public buildings. An arsenal on Greenleaf’s Point, about two miles south of the Capitol, exploded while the British were preparing to destroy it. Thirty men were killed and 45 were injured. Then a freak storm suddenly erupted, with high winds and violent thunder and lightning. The shaken British commanders soon retreated to their ships; the raid on the capital had ended.

Meanwhile, Dolley had received a note from Madison urging her to join him in Virginia. By the time they were finally reunited there on the night of August 25, the 63-year-old president had barely slept in several days. But he was determined to return to Washington as soon as possible. He insisted that Dolley remain in Virginia until the city was safe. By August 27, the president had re-entered Washington. In a note written hastily the next day, he told his wife: “You cannot return too soon.” The words seem to convey not only Madison’s need for her companionship but also his recognition that she was a potent symbol of his presidency.

On August 28, Dolley joined her husband in Washington. They stayed at the home of her sister Anna Payne Cutts, who had taken over the same house on F Street that the Madisons had occupied before moving to the White House. The sight of the ruined Capitol—and the charred, blackened shell of the White House—must have been almost unbearable for Dolley. For several days, according to friends, she was morose and tearful. A friend who saw President Madison at this time described him as “miserably shattered and woebegone. In short, he looks heartbroken.”

Madison also felt betrayed by General Winder—as well as by his Secretary of War, John Armstrong, who would resign within weeks—and by the ragtag army that had been routed. He blamed the retreat on low morale, the result of all the insults and denunciations of “Mr. Madison’s War,” as the citizens of New England, the center of opposition, labeled the conflict.

In the aftermath of the British rampage through the nation’s capital, many urged the president to move the government to a safer place. The Common Council of Philadelphia declared its readiness to provide housing and office space for both the president and Congress. Dolley fervently maintained that she and her husband—and Congress—should stay in Washington. The president agreed. He called for an emergency session of Congress to take place on September 19. Meanwhile, Dolley had persuaded the Federalist owner of a handsome brick dwelling on New York Avenue and 18th Street, known as the Octagon House, to let the Madisons use it as an official residence. She opened the social season there with a crowded reception on September 21.

Dolley soon found unexpected support elsewhere in the country. The White House had become a popular national symbol. People reacted with outrage when they heard that the British had burned the mansion. Next came a groundswell of admiration as newspapers reported Dolley’s refusal to retreat and her rescue of George Washington’s portrait and perhaps also a copy of the Declaration of Independence.

On September 1, President Madison issued a proclamation “exhorting all the good people” of the United States “to unite in their hearts and hands” in order “to chastise and expel the invader.” Madison’s former opponent for the presidency, DeWitt Clinton, said there was only one issue worth discussing now: Would the Americans fight back? On September 10, 1814, the Niles’ Weekly Register, a Baltimore paper with a national circulation, spoke for many. “The spirit of the nation is roused,” it editorialized.

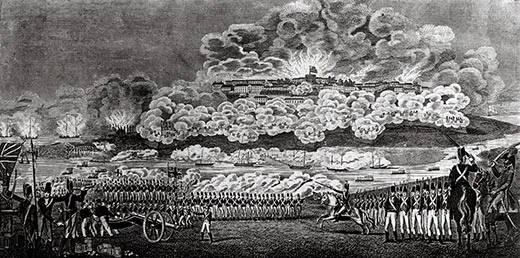

The British fleet sailed into the port of Baltimore three days later, on September 13, determined to batter Fort McHenry into submission—which would allow the British to seize harbor ships and to loot waterfront warehouses—and force the city to pay a ransom. Francis Scott Key, an American lawyer who had gone aboard a British flagship at the request of President Madison to negotiate the release of a doctor seized by a British landing party, was all but certain that the fort would surrender to a nightlong bombardment by the British. When Key saw the American flag still flying at sunrise, he scribbled a poem that began, “Oh say can you see by the dawn’s early light?” Within a few days, the words, set to the music of a popular song, were being sung all over Baltimore.

Good news from more distant fronts also soon reached Washington. An American fleet on Lake Champlain won a surprise victory over a British armada on September 11, 1814. The discouraged British had fought a halfhearted battle there and retreated to Canada. In Florida, after a British fleet arrived in Pensacola Bay, an American Army commanded by Gen. Andrew Jackson seized Pensacola (under Spanish control since the late 1700s) in November 1814. Thus, the British were deprived of a place to disembark. President Madison cited these victories in a message to Congress.

But the House of Representatives remained unmoved; it voted 79-37 to consider abandoning Washington. Still, Madison resisted. Dolley summoned all her social resources to persuade the congressmen to change their minds. At Octagon House, she presided over several scaled-down versions of her White House galas. For the next four months, Dolley and her allies lobbied the legislators as they continued to debate the proposal. Finally, both houses of Congress voted not only to stay in Washington but also to rebuild the Capitol and White House.

The Madisons’ worries were by no means over. After the Massachusetts legislature called for a conference of the five New England states to meet in Hartford, Connecticut, in December 1814, rumors swept the nation that the Yankees were going to secede or, at the very least, demand a semi-independence that could spell the end of the Union. A delegate leaked a “scoop” to the press: President Madison would resign.

Meanwhile, 8,000 British forces had landed in New Orleans and clashed with General Jackson’s troops. If they captured the city, they would control the Mississippi River Valley. In Hartford, the disunion convention dispatched delegates to Washington to confront the president. On the other side of the Atlantic, the British were making outrageous demands of American envoys, headed by Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin, aimed at reducing the United States to subservience. “The prospect of peace appears to get darker and darker,” Dolley wrote to Gallatin’s wife, Hannah, on December 26.

On January 14, 1815, a profoundly worried Dolley wrote again to Hannah: “The fate of N Orleans will be known today—on which so much depends.” She was wrong. The rest of January trickled away with no news from New Orleans. Meanwhile, the delegates from the Hartford Convention reached Washington. They were no longer proposing secession, but they wanted amendments to the Constitution restricting the president’s power, and they vowed to call another convention in June if the war continued. There was little doubt that this second session would recommend secession.

Federalists and others predicted New Orleans would be lost; there were calls for Madison’s impeachment. On Saturday, February 4, a messenger reached Washington with a letter from General Jackson reporting that he and his men had routed the British veterans, killing and wounding about 2,100 of them with a loss of only 7. New Orleans—and the Mississippi River—would remain in American hands! As night fell and the news swept through the nation’s capital, thousands of cheering celebrants marched along the streets carrying candles and torches. Dolley placed candles in every window of Octagon House. In the tumult, the Hartford Convention delegates stole out of town, never to be heard from again.

Ten days later, on February 14, came even more astonishing news: Henry Carroll, secretary to the American peace delegation, had returned from Ghent, Belgium. A buoyant Dolley urged her friends to attend a reception that evening. When they arrived, they were told that Carroll had brought a draft of a peace treaty; the president was upstairs in his study, discussing it with his cabinet.

The house was jammed with representatives and senators from both parties. A reporter from The National Intelligencer marveled at the way these political adversaries were congratulating each other, thanks to the warmth of Dolley’s smile and rising hopes that the war was over. “No one... who beheld the radiance of joy which lighted up her countenance,” the reporter wrote, could doubt “that all uncertainty was at an end.” This was a good deal less than true. In fact, the president had been less than thrilled by Carroll’s document, which offered little more than an end to the fighting and dying. But he decided that accepting it on the heels of the news from New Orleans would make Americans feel they had won a second war of independence.

Dolley had shrewdly stationed her cousin, Sally Coles, outside the room where the president was making up his mind. When the door opened and Sally saw smiles on every face, she rushed to the head of the stairs and cried: “Peace, Peace.” Octagon House exploded with joy. People rushed to embrace and congratulate Dolley. The butler began filling every wineglass in sight. Even the servants were invited to drink, and according to one account, would take two days to recover from the celebration.

Overnight, James Madison had gone from being a potentially impeachable president to a national hero, thanks to Gen. Andrew Jackson’s—and Dolley Madison’s—resolve. Demobilized soldiers were soon marching past Octagon House. Dolley stood on the steps beside her husband, accepting their salutes.

Adapted from The Intimate Lives of the Founding Fathers by Thomas Fleming. Copyright © 2009. With the permission of the publisher, Smithsonian Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.