How Central Park’s Complex History Played Into the Case Against the ‘Central Park Five’

The furor that erupted throughout New York City cannot be disentangled from the long history of the urban oasis

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/cf/55cf2d06-e208-4886-b6e0-b4f1e0f6abdb/gettyimages-120389580.jpg)

For more than a century, New York City’s Central Park was the soothing natural counter to the steel and concrete chaos. Designed to be an amalgam of the best parts of nature, the park, though it had its ups and downs, played a special role as the leafy-green heart of the city.

So, when news of a brutal attack in the park swept the city on April 19, 1989, the public outcry was enormous. The assault and rape of an unnamed victim, a woman since identified as Trisha Meili but then only known as “the jogger,” was plastered across headlines for months. Even the media shorthand for the case revealed the significance of the crime’s setting—the five boys accused of the crime became forever known as the “Central Park Five.”

“Central Park was holy,” said Ed Koch, mayor of New York at the time of the attack, in Ken Burns’ 2012 documentary on the case. “If it had happened anyplace else other than Central Park, it would have been terrible, but it would not have been as terrible.”

All five of the teenage defendants—Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, Korey Wise and Antron McCray—were found guilty and served between 6 and 13 years in prison. Most of the evidence against them came from a series of written and videotaped confessions, which, during the two trials, the boys said were coerced; DNA evidence from the crime scene produced no matches. Still, both juries, as well as most of the New York tabloids, were convinced of the teenagers’ guilt. The story of the case is retold in the new Netflix miniseries "When They See Us," which premieres today.

But in 2002, the case re-opened when Matias Reyes, a serial rapist serving a prison sentence for other crimes, confessed as the sole attacker in the Central Park case. His DNA and his account of the attack matched the original evidence. A judge vacated the Central Park Five’s convictions later that year, after the defendants had all served out their sentences, and New York was left to once more reckon with a case that had been closed for years.

Within that reckoning lay the question: Why had this case become so closely tied with the identity of Central Park? Maybe it was because a brutal attack on park grounds was such a perversion of the park’s original mission to serve as a calming and even civilizing space for all the city’s residents. Or maybe it was because such an occurrence exposed how that mission, and the city’s egalitarian project, had never been fully realized.

***

In the mid-19th century, New York’s population boomed as immigrants flooded in, particularly from Ireland, and as American-born migrants fled country farms for city life in an ever-industrializing nation. Even as buildings sprouted rapidly across the city, conditions grew ever more cramped and hazardous. Amid this increasing city-wide claustrophobia, some New Yorkers began to call for a park where green spaces could provide a healing respite for city dwellers.

“Commerce is devouring inch by inch the coast of the island, and if we would rescue any part of it for health and recreation it must be done now,” wrote William C. Bryant, editor of the New York Evening Post and a leading advocate for Central Park’s creation, in an 1844 editorial.

Of course, some motives for creating the park were more paternalistic, as city elites thought a cultivated, natural area could help “civilize” the New York underclass. Others were more business-minded, as realtors knew beautifying undeveloped land would raise property values for surrounding properties. In any case, state legislators were convinced, and set out to build the first major landscaped public park in the United States.

The city landed upon the 700-acre Manhattan expanse where the park still rambles to this day, sprawling out between Fifth and Eighth Avenue and from 59th Street to 106th Street (later expanded a few blocks to 110th). Because of its rough terrain, in which swampy muck alternated with harsh rock, the area didn’t hold much appeal for real estate developers, and in 1853, the city used its power of eminent domain to claim the land as public property and begin its transformation.

From the beginning, though, the park had an element of controversy: When the city tapped the area for its own use, more than 1,600 people already lived on the future park’s land. Hundreds were occupants of Seneca Village, a community established by free African-American property owners in 1825, two years before slavery was abolished in New York. Once the city claimed the land, police forcibly evicted Seneca Village residents, who probably scattered throughout the New York area. The community’s houses, churches and school were razed to make way for the rolling landscape designs of Olmsted and his design partner, Calvert Vaux.

In Olmsted’s eyes, the park would be a great equalizer among New York’s stratified classes. He’d been inspired by gardens in Europe, and especially by a visit to Birkenhead Park, the first publicly funded park in England. He noted that the site was enjoyed “about equally by all classes,” unlike most of the other cultivated natural grounds at the time, which were privately held by the wealthy elite.

A similar park would be, for Olmsted, an important part of the “great American democratic experiment,” says Stephen Mexal, an English professor at California State University Fullerton who has researched Central Park and its role in the Central Park Five case.

“There was a link that he thought was meaningful between genteel manners, people of genteel birth and genteel landscapes,” Mexal says. “And he said, ‘Well, what if we just kind of took those landscapes and made them more available to everybody?’ So, he said that the park would have this, quote, ‘refining influence’ among everybody in the city.”

Olmsted and Vaux’s “Greensward Plan” beat out more than 30 other entries in a public contest, promising sweeping pastoral expanses and lush greenery. Their vision came to life quickly, and by 1858 the first section of the park opened to the public. Millions of visitors poured into the park in its first years. Families flocked to skate on the lake in winter, and the fashionable New York set paraded into the park in carriages to socialize. Strict rules tried to set a tone of tranquil decorum in the park, prohibiting rowdy sports, public concerts and even walking on the wide grass lawns.

For a time, it seemed like Olmsted’s dream was fulfilled: He’d created a beautiful green respite in the middle of the city’s chaos, an idealized image of nature for all to enjoy.

“There is no other place in the world that is as much home to me,” Olmsted wrote of Central Park. “I love it all through and all the more for the trials it has cost me.”

Olmsted, however, may not have been prepared for the reality of a true “park for the people.” As the 19th century wore on, more working-class citizens and immigrants began frequenting the park, disrupting the “genteel” air its creator had so carefully cultivated on their supposed behalf. Sunday afternoon concerts, tennis matches, carousel rides and lawn picnics became important pieces of the park’s new character.

Though Olmsted bemoaned the “careless stupidity” with which many misused his perfectly groomed landscape, his democratic experiment, once set in action, could not be reeled in. Ultimately, even Olmsted’s best efforts couldn’t bring about harmony in the city. As New York continued its growth into the next century, Central Park, intended to be an outlet to relieve the pressures of city living, instead became a microcosm for the urban condition—its use reflecting the changing tides of its country.

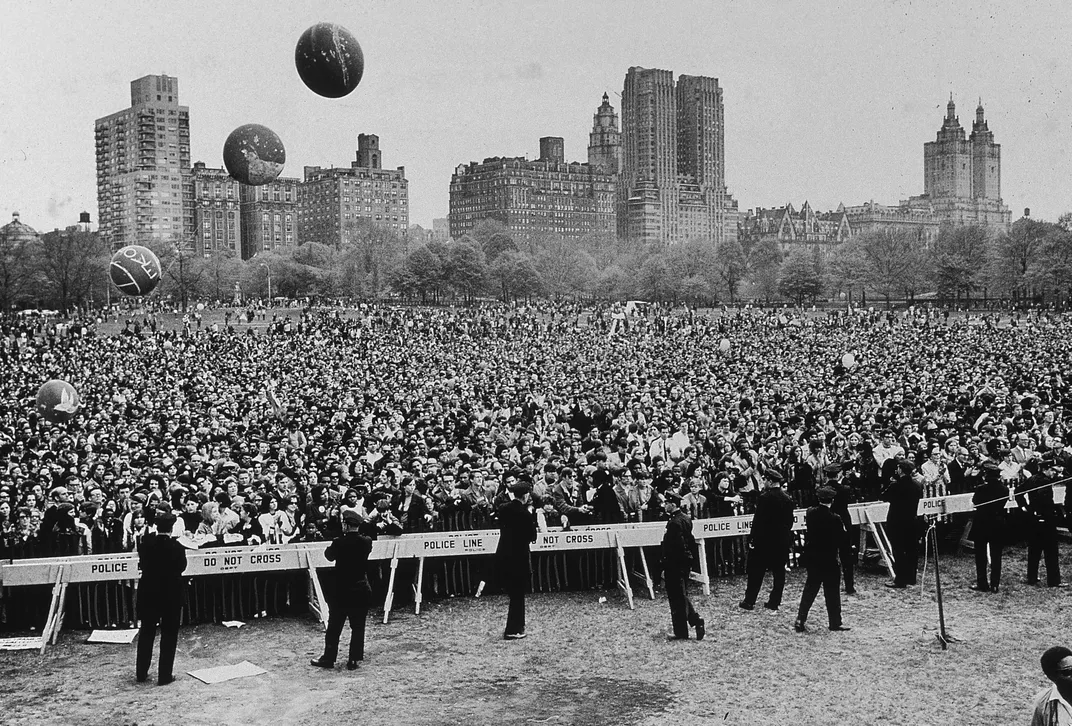

In the 1940s, newspapers latched onto the idea of a “crime wave” in the park after a young boy was murdered, a fear that persisted even though Central Park remained one of the safest precincts in the city. Protesters filled the park’s lawns in the 1960s, staging counterculture “be-ins” to speak out against racism and the Vietnam War.

The park gradually fell into disrepair, and though the city government made some efforts at undoing the century’s worth of damage upon Olmsted’s carefully designed structures and landscapes, in the 1970s the city’s financial crisis sapped city funds and park conservation fell by the wayside.

In 1975, a New York Times reporter lamented the park’s “state of galloping decay,” noting the “boarded windows, broken stonework and weed-gouged mortar” of the park’s famous Belvedere Castle.

“It can stand as a symbol of the decline of the park—the slow death of the Olmsted landscape in spite of spotty first aid and the private generosity that rebuilds an occasional bit of token architectural design,” the reporter wrote.

The decaying park, in turn, could stand as a symbol of the struggling city surrounding it. During the decade or so leading up to the Central Park Five case, New York City was a powder keg of competing fears and tensions. The crack-cocaine epidemic emerged as a major threat in the early 1980s. Homelessness swelled at the same time as a growing financial sector brought immense wealth to a select few. Violent crimes climbed ever higher, with a record 1,896 homicides reported in 1988.

When the Central Park jogger attack was reported, it ignited that powder keg, setting off widespread public outrage and a media firestorm.

One word in particular became a centerpiece for coverage of the case: “wilding.” Police reported that the boys had used the term to describe the attack’s motive, or rather, its lack thereof. The concept of “wilding”—roaming around and wreaking havoc, just for the fun of it—sparked fascination and terror. “Park marauders call it ‘wilding’ … and it’s street slang for going berserk,” the New York Daily News proclaimed.

The obsession over this concept, of totally random and gleeful criminality, helped fuel the continuing fervor over the case, Mexal says.

“That crime captured the public's attention for a number of reasons. Partially because it was the assault of a white woman by, they thought, non-white males,” he says. “But also because of the beliefs about nature, savagery and wilderness that the word ‘wilding’ seem to conjure, especially when it was put against this backdrop of Central Park, which is a built environment that is a stylized recreation of a natural space.”

The park was supposed to be a sanitized version of nature, Mexal explains—one that substituted calm civility for genuine wilderness and the danger that came with it. A pattern of “wilding” through the park’s cultivated landscapes would show a failure of this attempt to conquer the natural world.

Media coverage took this idea of “wildness” and ran with it. Newspapers repeatedly referred to the five defendants in sub-human terms: They were a “wolf pack,” “savages,” “monsters,” with the unsuspecting woman as their “prey.” In addition to following a long tradition of dehumanizing language about African-Americans, such headlines fed into the outrage that seemed to spring up any time something went wrong in Central Park.

Even through varying states of disarray, the park remained close to New Yorkers’ hearts. In the 1980s, commentators still referred to Central Park as “the most popular and democratic space in America” or as “the one truly democratic space in the city,” as Elizabeth Blackmar and Roy Rosenzweig write in their historical account of Central Park. Meili, the victim of the attack, recalled her love for running in the park, a routine she followed most days of the week.

"It was a release to be out there in nature, to see the beauty of the park ... as well as the skyscrapers and the lights of New York City, and the sense that, 'Wow, this is my city. I'm here in my park,’" Meili told ABC News in a recent interview. "I loved the freedom of the park. ... It just gave me a sense of vitality."

It follows that any crime in the park became all the more personal for New Yorkers because of its setting. Crime in Central Park “shock[ed] people like crime in heaven,” as one captain of the park police precinct said.

The Central Park Five case has been, at various points, a terrifying example of pointless crime, and a chilling story of false convictions; it has sparked cries to bring back the death penalty, and to reform the criminal justice system.

The case and its coverage have also been deeply shaped by the setting of the crime in question—a manmade piece of nature that represents its city not despite its many conflicts and paradoxes, but because of them.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Maddie_3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Maddie_3.jpg)