Grace Under Fire

As San Francisco burned, 100 years ago this month, a hardy band of men worked feverishly to save the city’s mint—and with it, the U.S. economy

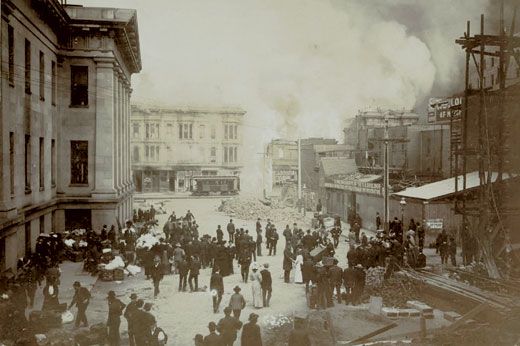

Like a dog shaking a rag doll, the most destructive earthquake in American history shook San Francisco at 5:12 a.m. on April 18, 1906. It ruptured gas lines and ignited dozens of fires, many of which soon merged into the disaster's single largest blaze. Eyewitnesses estimated that this "fire fiend," as one observer called it, reached 20 stories high. Its temperature exceeded 2,000 degrees, hot enough to melt steel.

With its water mains damaged by the quake, the city surrounded on three sides by water found itself unable to quench the flames, which burned out of control for three days. By the time the last embers were finally out, five square miles had been incinerated, some 28,000 buildings were destroyed, and an estimated 3,000 people were dead.

On that first morning 100 years ago, thousands of dazed San Franciscans—shaken by the earthquake and choked by smoke—grabbed what they could and fled for their lives. They caught ferries across the bay to Oakland or made their way to hastily established refugee camps in Golden Gate Park and around the edges of the city.

But right in the path of the largest, hottest blaze, a few dozen men at the San Francisco Mint, where coins were manufactured for circulation, stood fast. Led by a political appointee with no experience in crisis management, they fought back against an inferno that melted the glass in the mint's windows and burned the clothes off their backs. They didn't consider themselves heroes; their accounts of that hellish day are remarkably matter-of-fact. But heroes they were, brave and a bit lucky. Although their story is largely forgotten, by safeguarding gold and silver worth $300 million—the equivalent of more than $6 billion today—they may have saved the U.S. economy from collapse.

At the time gold was first discovered near Sacramento in 1848, California was a collection of sleepy Mexican villages with a population of 15,000. Barely two years later, when California entered the Union as the 31st state, its population had soared to nearly 100,000.

But the new state's development was hampered by monetary chaos. Small transactions were handled by barter; for larger ones, gold dust was the leading medium of exchange. As hordes of gold seekers flooded the Golden State, legal tender also included Mexican reals, French louis d’ors, Dutch guilders, English shillings, Indian rupees, and U.S. dollars and coins struck by some 20 private mints. These mints sprang up to handle the bags of nuggets that came down from the diggings to San Francisco, the state's financial and population center. "It was clear," says Charles Fracchia of the San Francisco Museum and Historical Society, "that California needed standardized currency."

To end the confusion, Congress authorized a U.S. mint in San Francisco to begin operation in 1854. Within a year the tiny mint—just 60 square feet—had turned $4 million worth of gold bullion into U.S. coins. When tons of silver began pouring into San Francisco after the discovery of Nevada's Comstock Lode in 1859, the Treasury Department needed a larger mint. It acquired a city block in a run-down neighborhood of boarding houses, cheap hotels and tenement apartments—built, like most of San Francisco, of wood.

The mint that would rise on the site, then known as the New Mint, was designed by Alfred B. Mullett, architect of the Old Executive Office Building in Washington, D.C. The building, inspired by Greek temples, opened in 1874: "The fire department," exulted the daily San Francisco Call, "will have little trouble quenching any conflagration that may arise within its walls." With a price tag of $2.1 million—which wouldn't buy half the land under it today—the stately three-story edifice was constructed around a large central courtyard with a well, and featured granite stairs rising from the street to a dramatic portico with fluted sandstone columns. Inside, the rooms boasted marble fireplaces and Honduran mahogany woodwork. Elaborate iron railings lined the interior stairs. The entire building sat on a granite-and-concrete foundation five feet deep, designed to keep thieves from tunneling into the vaults. Although little beyond the base and the outdoor staircase was granite, someone dubbed the building the Granite Lady, and the name stuck.

The New Mint's grandeur contrasted sharply with the dilapidation of the surrounding tenements. But the building's location in a working-class neighborhood was fitting: the mint, after all, was an industrial building, a factory that churned out money. By 1880, the Granite Lady was producing 60 percent of U.S. gold and silver coins, and until the Fort Knox depository opened in 1937, its vaults would hold fully a third of the country's gold reserves.

A few dozen of the mint's 150 employees had worked the overnight shift. Their workday was winding down just before sunrise on April 18. In a letter to his brother three weeks later, one of them, Joe Hammill, recalled being suddenly "thrown in every direction." The quake toppled much of the mint's furniture, but thanks to its thick stone foundation, unusual among early 20th-century San Francisco buildings, the structure itself suffered no significant damage.

Shortly after the shaking stopped, the crew spotted fires springing up in the tenements around them. Night supervisor T. W. Hawes instructed the men to close and lock the iron security shutters on the mint's ground-floor windows, normally left slightly open to admit light. To keep the blazes away from the mint's wooden window frames and other potential points of entry, Hawes ordered the men to remove everything flammable from around the building's exterior, and to use water from the courtyard well to extinguish any encroaching fires.

The well was an uncommon feature among San Francisco's major buildings. And in a stroke of astonishing good luck, just ten days before the quake plumbers had completed installing internal fire hoses around the building—a recent construction innovation. But the quake had damaged the mint's water pump. As the men scrambled to repair it, Hawes directed them to douse the fires around the building with, of all things, a mixture of sulfuric and hydrochloric acid, barrels of which were kept inside the mint to manufacture coins.

After about an hour, with small fires now surrounding the building, an engineer named Jack Brady got the pump to work. But while the flowing water was a welcome sight, Hawes needed more men—and San Francisco firemen, busy elsewhere, were nowhere in sight. Help came from Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston, San Francisco's ranking military officer. Worried that criminal gangs from the city's notorious Barbary Coast might attack the mint and loot its vaults, Funston dispatched a squad of ten soldiers to aid in the building's defense. Along with a few day-shift employees who lived nearby and had rushed to the mint to lend a hand, the soldiers brought the number of defenders to around 60.

Burning ash rained down from the smoke-filled sky onto the mint's roof, which was littered with debris from recent construction. Hawes put the reinforcements to work immediately, ordering "everything on the roof that would burn thrown into the [court]yard," wrote mint employee Harold French.

By around 9 a.m., Hawes had done all he could to secure the mint. But refugees fleeing past the building from downtown brought news of huge fires that seemed to be merging into one horrific conflagration—headed right for the mint. Hawes must have wished that his boss, Mint Superintendent Frank Leach, were at his post. But Leach lived across the bay in Oakland, an almost unimaginable journey in the postquake chaos.

Yet Leach was just two blocks away at the corner of Market and Powell streets—where rifle-toting soldiers, positioned along Market Street since martial law was put in force less than three hours after the quake, were refusing to let him pass.

There was little in Frank Leach's biography to expect great acts of heroism. Before being named by President McKinley in 1897 to head the mint, he'd spent most of his adult life running small newspapers around Northern California, with a two-year detour in the California Legislature as a Republican representative.

Now, unable to cross the police lines to get to the mint, he was faced with the prospect of losing not only the most beautiful building west of Denver but also, and more important, some $300 million in its vaults. Still in the consciousness of Americans at the dawn of the 20th century was the Panic of 1857, a three-year economic downturn triggered in part by the loss of 15 tons of California gold when the SS Central America sank in a hurricane off the coast of the Carolinas. Leach could only imagine the consequences if the mint gold—nearly 30 times the value of that carried by the Central America—were to be lost.

Leach had been asleep at home when the earthquake struck; he later recalled that the temblor "seemed to threaten to tear our house to pieces....Then there were the terrifying noises...the cracking and creaking of timber....the smashing and crashing of falling glass....And the thumping of falling bricks...from the chimney tops....The air was filled with dust. It seemed as if the shaking would never cease....For a few seconds I [thought] the end of the world had been reached."

After establishing that his family was safe, Leach rushed to the ferry terminal determined to get to the mint. Across the bay, pillars of smoke were already rising over San Francisco. The ferries bringing refugees to Oakland were returning to San Francisco without passengers, with entry to the stricken city sealed off. But Leach explained his position to a ferry official, who allowed him to board.

As his boat approached San Francisco, Leach took in "a terrible sight....Great clouds of black smoke...hid the rays of the sun. Buildings in the track of the rapidly spreading fire went down like houses of cardboard." The mint was just 12 blocks up Market Street from the ferry terminal, normally a 20-minute walk. But when he disembarked, Leach found Market Street to be "a mass of flames," so he was forced to circle north to skirt the devastation. Finally, perhaps 90 minutes after arriving in San Francisco, Leach reached Market and Powell, today the downtown terminus of the Fisherman's Wharf cable car line. There soldiers blocked his path, ignoring his pleas until, at last, a police officer recognized him and personally escorted him to the mint.

When Leach arrived, he found the mint employees and the ten soldiers going "about the work in a simple, every-day manner, but nevertheless with earnest, willing, and active spirit. I felt proud to be Superintendent of that band of faithful and brave men." He applauded Hawes’ "excellent judgment": the decision to move everything flammable from around the doors and windows had prevented the small fires in the immediate vicinity from entering the Granite Lady.

But in the distance, flames were larger and growing. Leach divided the men into squads, positioning them on all four floors and on the roof, and instructed them to douse the building's interior with water, especially its window frames and mahogany woodwork. Wherever the hoses couldn't reach, he organized bucket brigades.

At 1 p.m., Leach surveyed the city from the mint’s roof. "Our position look[ed] rather perilous," he later wrote in a memoir. "It did not seem probable that the structure could withstand the terrific mass of flames that was sweeping down upon us." If he had to abandon the mint, to "preserve the lives of the brave men defending the property," his plan was to retreat south, where many tenements had already burned. He could see that the area was charred wreckage—still hot, but cooling and, he thought, passable.

Suddenly, the fire was upon them: "Inside, the building was made almost dark as night by a mass of black smoke that swept in upon us just ahead of the advancing flames," Leach wrote. Then came "a tremendous shower of red hot cinders that fell on our building as thick as hail, and piled up on the roof in drifts nearly two feet deep...for a distance of twenty feet." Sparks and cinders fell on wood lying in the building's central courtyard, starting "a dozen little fires." Flames had finally breached the mint's walls.

Leach and his men knew that if they failed to contain the fires in the courtyard, the mint would be lost. But as soon as they extinguished one blaze, the rain of cinders ignited another. "I show[ed] a soldier who was handling one line of hose how to get the most efficiency from the stream of water," Leach later recalled. Almost immediately, burning cinders scorched their clothes.

Sometime in the afternoon, their luck turned: probably because of a shift in wind, the hail of burning cinders abated. By this time, the men had drenched everything in the courtyard, so Leach sent them to the mint's upper floors, where, he wrote, "the hardest struggle against the flames would soon take place."

The mint's north side faced a narrow alley; across it, everything was ablaze. "Great masses of flame shot against the side of our building," Leach wrote, "as if directed against us by a huge blow-pipe." The new fire hoses that had appeared so powerful just days earlier now looked as puny as squirt guns. The heat was so intense that "the glass in our windows," Leach continued, "did not crack and break, but melted down like butter." Joe Hammill observed, "We were prisoners and fighting for our lives."

Stone heated to high temperatures produces popping sounds, and the mint's enormous mass of granite and sandstone created what Harold French described as "thunder" like "the deafening detonations" of "thirteen-inch shells against the walls." Leach noted that "at times the concussions from the explosions were heavy enough to make the floor quiver."

With glass melted out of so many windows, Leach watched as "great tongues of flame" darted into the building, setting the interior woodwork ablaze. With the hose and buckets in relays, the men "dashed into the rooms to play water on the flames," Leach recalled. The men stayed in the rooms, which Leach called "veritable furnaces," for "as long as they could hold their breaths," and "then came out to be relieved by another crew of willing fighters." Joe Hammill remembered that "we stuck to the windows until they melted, playing a stream of water on the blazing woodwork. Then, as the flames leaped in and the smoke nearly choked us, we were ordered downstairs." So far, the mint's treasure lay safe in its basement vaults. But now, Hammill wrote, "It [appeared] the Mint was doomed."

Leach, too, feared the worst. Then, "to our surprise," the smoke cleared. The men, "with a cheer," he wrote, "went dashing into the fight again."

The smoke in the building's interior waxed and waned, depending on the wind and on the material burning in nearby buildings. The men lost track of time, dousing water on the flames every time the strangling smoke let up. Then, by midafternoon, Leach realized that "the explosions of the stones in our walls grew fainter, and finally we heard no more of them." That could mean only one thing. The conflagration had passed by the mint at last on its march westward through the city.

But the roof was still on fire. The men, Hammill wrote, "climbed out onto the roof and played the hose on the red-hot copper surface....We worked for an hour, ripping up sheet copper and...using the hose where [it] would do the most good."

As Hammill and his comrades worked on the roof, Leach toured the building—finding, to his great relief, no serious damage. "The fight was won," he later wrote. "The Mint was saved."

Around 5 p.m., Frank Leach stepped outside for the first time in hours. The view "was one of utter ruin, desolation, and loneliness." Neighboring buildings "were piles of smoking ruins. Not a human being was to be seen. It seemed as if all the people and buildings of the city but the Mint and its defenders had been destroyed."

No Barbary Coast gangs had attacked the mint (although that didn’t stop the Oakland Tribune from reporting erroneously, in a postquake edition, that 14 people had been shot trying to rob it). When martial law ended, the Granite Lady became a centerpiece of San Francisco's rebirth. Residents returning to the charred ruins of their homes found that the mint had the only potable water in the area. Leach installed pipelines from the mint's well to distribute water to residents until the mains could be repaired. Because of the people lined up for water, the neighborhood's first businesses to reopen after the fire set up in tents around the building. The mint also functioned as a bank for the federally sanctioned wire transfers that poured in from around the country—$40 million in the first two weeks alone, about $900 million in today's dollars.

For his efforts, Frank Leach earned a promotion to director of the mint in Washington, D.C. and the undying loyalty of his men. "Through his coolness and ability," Joe Hammill later wrote, "the men under him worked to the best advantage. He took his turn at the hose with the others, and did not ask his men to go where he would not go himself. It is remarkable how he stood the strain of the fire." The same could be said of the brave men who stood beside him, and saved not only the mint but perhaps also the U.S. economy itself.

Three decades after Frank Leach and his men saved the nation's gold, the Treasury Department opened a more modern mint, the New Mint, about a mile from the Granite Lady, which has been known ever since as the Old Mint (the last coin was minted there in 1937). In 1961, the Old Mint was declared a National Historic Landmark. The federal government began using it as office space in 1972, sharing the building with a small numismatic museum. Then, in 1994, the Treasury Department closed the building.

In 2003, the federal government sold the Old Mint to the city of San Francisco for one dollar—a silver dollar struck at the mint in 1879. The city then proceeded to give the building over to the San Francisco Museum and Historical Society, which plans to turn it into the San Francisco History Museum.

The $60 million restoration plan calls for seismic strengthening, and the transformation of the building's courtyard into a jewel-like galleria rising from ground level to a glass roof at attic level. Glass-walled elevators and bridges will allow wheelchair access and easy passage around the building. Plans for the Old Mint also include a welcome center for the city of San Francisco, a restaurant and—in the historical vaults—a numismatic museum. City officials expect some 350,000 visitors a year when the museum opens in late 2008 or early 2009.

At the restoration groundbreaking last fall, Mayor Gavin Newsom called the Old Mint "the soul of San Francisco." Says Gilbert Castle, former executive director of the San Francisco Museum and Historical Society, "We’re saving the mint again."

Survivor Tales

Each year, in dwindling numbers, they gather on April 18 to celebrate San Francisco’s endurance, and their own. All but one are now centenarians. They rise before dawn and are driven in vintage cars to Lotta’s Fountain on Market and Kearny streets, the main meeting place on the day of the great ’06 earthquake. Police and fire engine sirens wail at 5:12 a.m., the moment that made them all part of history.

Only six survivors showed up last year, but twice as many are expected to appear at this year’s centennial event. The eldest will likely be Herbert Hamrol, 103, who still works two days a week stocking shelves at a San Francisco grocery store. The baby of the group is Norma Norwood, 99, an honorary member who proudly calls herself “a result of the quake,” having been conceived the night of the disaster in a refugee tent in Golden Gate Park. “My father said it was cold that night in the tent, so they snuggled to keep warm,” she says. “They didn’t want a baby; they had no money, but I came anyway. That’s what happens when you snuggle.”

It was their generation’s Katrina. A city of 400,000 was flattened by a wallop of nature. An estimated 3,000 people died as a direct or indirect result of the quake and the fires that followed. More than half of San Francisco’s residents were left homeless.

But tragedy plus time has made for a celebration. For the past three decades, tracked down and annually united by publicist Taren Sapienza, the group has met at the St. Francis Hotel. They stay in champagne-stocked suites and rise in darkness. In past years, hundreds of other San Franciscans, including the mayor, have also roused themselves early to pay these stalwarts homage. “In my heart, these survivors represent the city that San Francisco became,” says Sapienza. “They personally may not have poured the cement and pounded the nails, but they rebuilt the city.”

Frances Mae Duffy, 11 months old at the time of the quake, appreciates the tribute and is trying her best to, literally, live up to it. “I sure do hope I make it,” she said in late February, noting that she was planning to buy a new feathered hat for the occasion. “It’s a wonderful thing, it brings everybody together from every walk of life,” she said of the ceremony. “No matter how rich or poor you were, you got shook up just the same.”

Understandably, few direct recollections of the quake remain among those who gather from as far away as Oregon and Arizona. “I have a slight memory of being carried down the stairs by my mother,” says Hamrol. “She held me in her left arm and her right arm held on to the banister.”

Frances Duffy remembers being told that her mother sneaked out of the refugee park, braving police on the lookout for looters, to retrieve a wedding ring left on her kitchen sink while she washed dishes. She never found it.

Norwood’s family, who lost their house in the quake, moved into a flat on Fell Street. Her father was a saloonkeeper, and at age 6, she says she’d dance for longshoremen who threw nickels and pennies on the floor.

It’s tempting to look for common traits among these last few—to suppose that something so momentous has somehow shaped their view of the world. Claire Wight, Frances Duffy’s daughter, believes this to be so. “Part of my mother’s belief system,” she says, “is that if you can survive something like that, the rest of life is gravy.”