Elizabeth Van Lew: An Unlikely Union Spy

A member of the Richmond elite, one woman defied convention and the Confederacy and fed secrets to the Union during the Civil War

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Elizabeth-Van-Lew-Civil-War-spy-631.jpg)

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Union and Confederate officers could never have predicted the role women would play in gathering information about the enemy. But as Northern and Southern women began providing critical intelligence on everything from the enemy’s movements to its military strategy, both sides began to actively recruit them as operatives. Over the course of the war, hundreds of women acted as undercover agents, willing to risk their lives to help their cause.

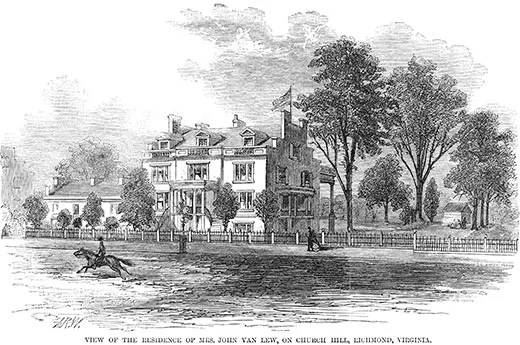

One of the most effective was Union spy Elizabeth Van Lew—a prominent member of Richmond, Virginia, society. The 43-year-old lived with her widowed mother in a three-story mansion in the Confederate capital. Educated in the North, Van Lew took pride in her Richmond roots, but she fervently opposed slavery and secession, writing her thoughts in a secret diary she kept buried in her backyard and whose existence she would reveal only on her deathbed.

“She believed that Virginia’s distinct and special role as the architect of the Union required it to do whatever it could to preserve and sustain the country,” said historian Elizabeth Varon, author of Southern Lady, Yankee Spy. “But she always pretended to be a loyal Confederate.”

As her wealthy neighbors celebrated Confederate victories, Van Lew quietly focused on helping the Union. Over the next four years she would send valuable intelligence to Union officers, provide food and medicine to prisoners of war and help plan their escapes, and run her own network of spies. “She is considered the most successful Federal spy of the war,” said William Rasmussen, lead curator at the Virginia Historical Society.

These triumphs for the Union, however, would ultimately cost Van Lew not only her family fortune but also her place as a member of Richmond’s social elite.

Libby Prison

Van Lew saw her first opportunity to help the Union after the Battle of Manassas in July 1861. Having no place to hold the Union prisoners pouring into Richmond, Confederates put them up in a tobacco warehouse. The now-infamous Libby Prison, as it was called, soon became known for its harsh conditions, where hundreds of men suffered from disease, hunger and despair.

Van Lew volunteered to become a nurse there, but her offer was rejected by the prison overseer, Lt. David H. Todd—the half-brother of Mary Todd Lincoln. Van Lew went over his head and used flattery and persistence to persuade Gen. John H. Winder to allow her and her mother to bring food, books and medicine to prisoners.

Van Lew and her mother were vehemently criticized for their efforts. The Richmond Enquirer wrote, “Two ladies, a mother and a daughter, living on Church Hill, have lately attracted public notice by their assiduous attentions to the Yankee prisoners…. these two women have been expending their opulent means in aiding and giving comfort to the miscreants who have invaded our sacred soil.”

Threats of violence quickly followed. “I have had brave men shake their fingers in my face and say terrible things,” she wrote. “We had threats of being driven away, threats of fire, and threats of death.” The Richmond Dispatch wrote that if the Van Lews didn’t stop their efforts, they would be “exposed and dealt with as alien enemies of the country.”

The bullying only made Van Lew more determined to help the Union. She passed information to prisoners using a custard dish with a secret compartment and communicated with them through messages hidden in books. She bribed guards to give prisoners extra food and clothing and to transfer them to hospitals where she could interview them. She even helped prisoners plan their escape, hiding many of them briefly in her home.

“One of the things that made women so effective as spies during this time period was that few people expected them either to engage in such ‘unladylike’ activity, or to have the mental capacity and physical endurance to make them successful,” said historian Elizabeth Leonard, author of All the Daring of the Soldier: Women of the Civil War Armies.

Union Spymaster

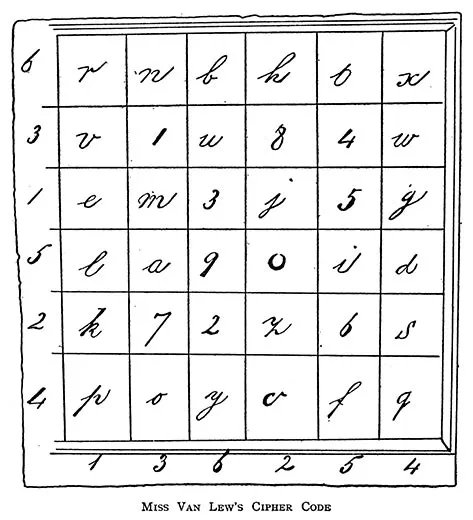

In December 1863, two Union soldiers who had escaped from Libby Prison with the help of Van Lew’s underground network told Union Gen. Benjamin Butler about Van Lew. Impressed with the stories, Butler sent one of the men back to Richmond with orders to recruit Van Lew as a spy. Van Lew agreed and soon became the head of Butler’s spy network and his chief source of information about Richmond. As instructed, Van Lew wrote her dispatches in code and in a colorless liquid, which turned black when combined with milk.

Her first dispatch, on January 30, 1864, informed Butler that the Confederacy was planning to ship inmates from Richmond’s overcrowded prisons to Andersonville Prison in Georgia. Her note suggested the number of forces he would need to attack and free the prisoners and warned him not to underestimate the Confederates. Butler immediately sent Van Lew’s report to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who ordered a raid, but the Confederate Army had been warned by a Union soldier on its payroll and successfully rebuffed the attack.

Though this attempt to free the prisoners failed, another one—this time by the prisoners themselves—had a better outcome. On February 14, 1864, one hundred Union officers escaped Libby Prison by digging a tunnel under the street—one of the most daring prison breaks of the war. Fewer than half were recaptured. The victory, however small, rallied the hopes of Northerners. Van Lew, however, became even more dedicated to helping the men still suffering in Richmond prisons, particularly those in Belle Isle Prison, which she visited after the Libby Prison escape. Of her stop there she wrote, “It surpassed in wretchedness and squalid filth my most vivid imagination. The long lines of forsaken, despairing, hopeless-looking beings, who, within this hollow square, looked upon us, gaunt hunger staring from their sunken eyes.”

On March 1, Union soldiers once again attempted to free Richmond’s prisoners but failed. Twenty-one-year-old Col. Ulric Dahlgren and Brig. Gen. H. Judson Kilpatrick led the raid. Dahlgren, who had lost his right leg at the Battle of Gettysburg, was killed in the skirmish and most of his men were captured. Confederate soldiers buried Dahlgren in a shallow grave the following day, but went back and dug up his body after hearing that papers found on Dahlgren proved he and his men were on a mission to kill Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The outraged men put Dahlgren’s body on display at a railroad depot, where crowds of onlookers gawked at it. His wooden leg and the little finger on his left hand were missing. After several hours, his body was taken down and, on orders of Confederate President Davis, secretly buried.

Van Lew was disgusted by the mutilation of Dahlgren’s body and promised “to discover the hidden grave and remove his honored dust to friendly care.” She asked her most trusted agents to help. Though the Confederates didn’t know it, one man had witnessed the secret burial and was able to tell Van Lew’s operatives where it had taken place. They dug up the body and reburied it until they could return it safely to Dahlgren’s family.

Grant’s Greatest Source

By June 1864, Van Lew’s spy network had grown to more than a dozen people. Along with the agents in government service, she relied on an informal network of men and women, black and white—including her African-American servant Mary Elizabeth Bowser. The group relayed hidden messages between five stations, including the Van Lew family farm outside the city, to get key information to the Union. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant later told Van Lew, “You have sent me the most valuable information received from Richmond during the war.”

After a long, exhausting campaign, Grant finally captured Richmond and Petersburg in April 1865. Van Lew’s work as a Union spymaster was without reproach, and she received personal thanks from Grant and several other Union officers. She was also given some money as payment for her efforts, but much of her personal fortune and all of her social standing were gone.

She was now labeled a spy—a term she thought cruel and unfair. “I do not know how they can call me a spy serving my own country within its recognized borders… [for] my loyalty am I now to be branded as a spy—by my own country, for which I was willing to lay down my life? Is that honorable or honest? God knows.”

Her fellow Richmonders couldn’t forgive her. She wrote, “[I am] held in contempt & scorn by the narrow minded men and women of my city for my loyalty … Socially living as utterly alone in the city of my birth, as if I spoke a different language.”

Her difficulties slightly improved after Grant became president in 1869 and appointed her postmaster of Richmond, a position she held for eight years. But when Rutherford B. Hayes took office as president, Van Lew lost her job and had almost no one to turn to for help.

Desperate, Van Lew, who was now in her 70s, contacted the family of Paul Revere, one of the Union officers she’d helped during the war and grandson of the famous Paul Revere. The family, along with other wealthy people in Boston whom Van Lew had helped during the war, regularly gave her money.

Van Lew survived on that income until she died at her home, still an outcast, in 1900.