Before Dr. Mutter, Surgery Was a Dangerous and Horrifically Painful Ordeal

The talented doctor changed the way the medical profession operated

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/80/9c80e808-b6ac-451b-b9fc-5cd4796cda3c/071amputationinstruments_main.jpg)

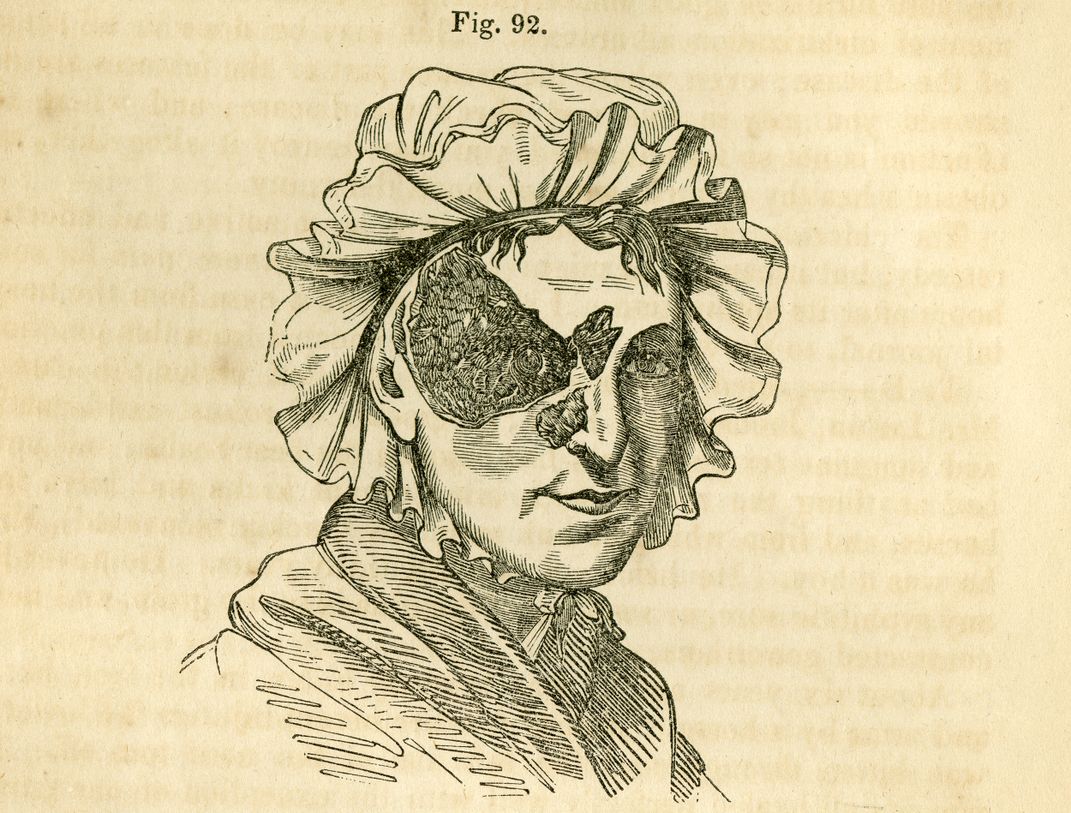

Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter’s story is not so surprising if you consider that a man did not need a medical degree to practice medicine in early 19th-century Philadelphia. In fact, he didn’t even need a license—a practice that Philadelphia would not embrace into the final decade of the 19th century. Although the tide was changing, the clear truth was that anyone who wanted to put out a shingle and call himself a doctor could do just that.

Basics of modern medicine, such as the infectiousness of diseases, were still under heavy dispute. Causes of even common diseases were confusing to doctors. Appendicitis was called peritonitis, and its victims were simply left to die. Bleeding the ill was still a widespread practice. There was no anesthesia – neither general nor local. If you came to a doctor with a compound fracture, you had only a 50 percent chance of survival.

But Mütter was a different kind of doctor and a different kind of teacher. By the end of the 1830s, Mütter, young, smart, ambitious, and blessed with extraordinary talents was gaining a reputation as “one of the best of good fellows” in the Philadelphia medical world and not just in the lecture hall.

“He possessed spontaneously, as it were, the art both of making and holding friends,” a fellow doctor would write of him, “a natural amenity of manner and gentleness of character, a manliness of bearing so intermingled with feminine graces that even children were attracted by it, and a love of approbation that induced him to do what he could to please others.”

When Dr. Thomas Harris, Mütter’s mentor, grew too sick to make house calls, he asked Mütter to go on his behalf. Mütter’s skill, matched with his comforting and charming demeanor, endeared him to the patients. Soon, other doctors, including and especially the ever-encouraging Dr. Samuel Jackson, made a habit of sending Mütter to make house calls in their stead. As a result, within a few months, Mütter began to develop a healthy private practice. He was also garnering an impressive reputation as a surgeon. His access to the Jefferson Medical School’s surgical rooms allowed him to attempt the kinds of ambitious surgeries he had learned about in Paris, many of which defiantly occupied “the difficult domain of reparative and reconstructive surgery.”

His first surgical patients found their way to him through the school itself, who promised citizens free surgical treatment, provided they agreed to the surgery’s being performed in a public setting. But it didn’t take long for Mütter to also begin receiving surgical patients privately as word of his unusual skills began to spread. The first patients came from the Philadelphia area, but soon, “strangers from various parts of this wide domain . . . sought from his skill the relief which their various sufferings demanded.”

“He succeeded with patients for the same reason as with students,” it was written of him; “he was both respected and liked.” This seemed like a welcome change from the relentless acrimony and open hostility that now marred the reputations of the city’s two top teaching surgeons. Mütter might have sensed that he was being groomed for something greater when three distinguished Philadelphia doctors—all several years his senior—independently approached him and inquired if they might assist him in one of his next surgeries radicals. They each wanted to see firsthand how Mütter took cases so damaged and tragic, and fixed them so seamlessly.

Perhaps the most sensible response would have been to have each doctor come in separately and then select patients whose surgeries would be easiest to perform in front of such an esteemed audience. But that wasn’t Mütter’s way. He knew it was risky, but he couldn’t help it. He decided to do a very difficult surgery, and asked all of them to be his assistants on it. It took some finessing, but Mütter assured them that each individual would serve a necessary part in the surgery. Still, it was quite a sight to see: men at the prime of their careers, lining up to assist a 29-year-old surgeon who was perhaps best known to their wives as the doctor who liked to match the color of his expensive suit to the carriage in which he was riding. But the simple truth was that the doctors were happy to line up by Mütter’s side, to witness his surgical prowess, to be close to his quick, sure hands.

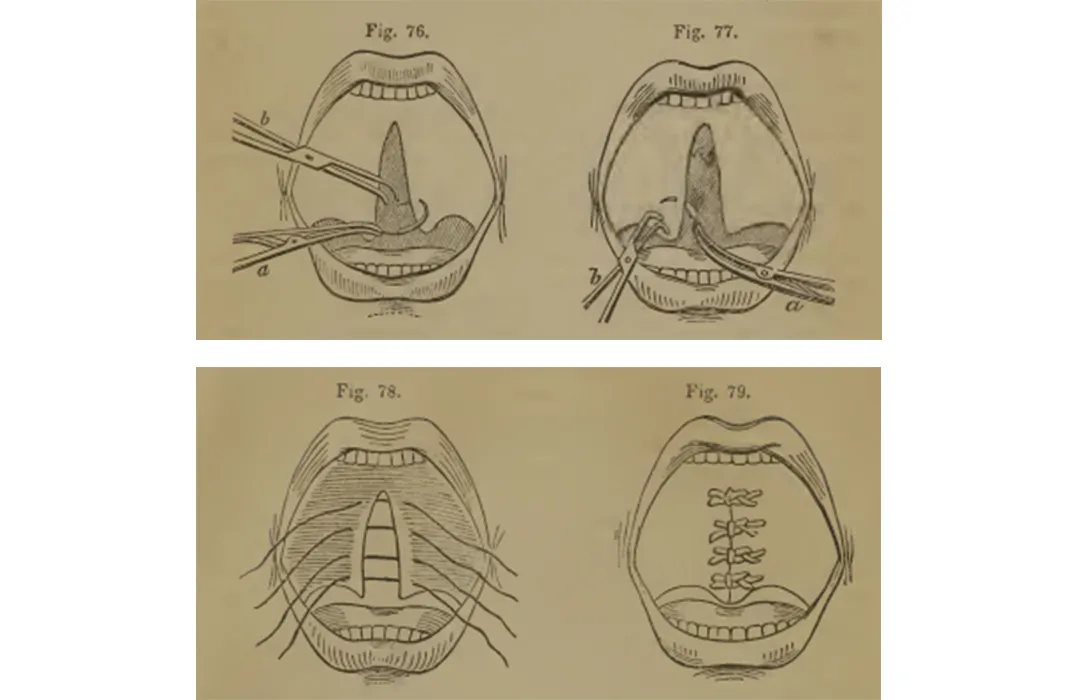

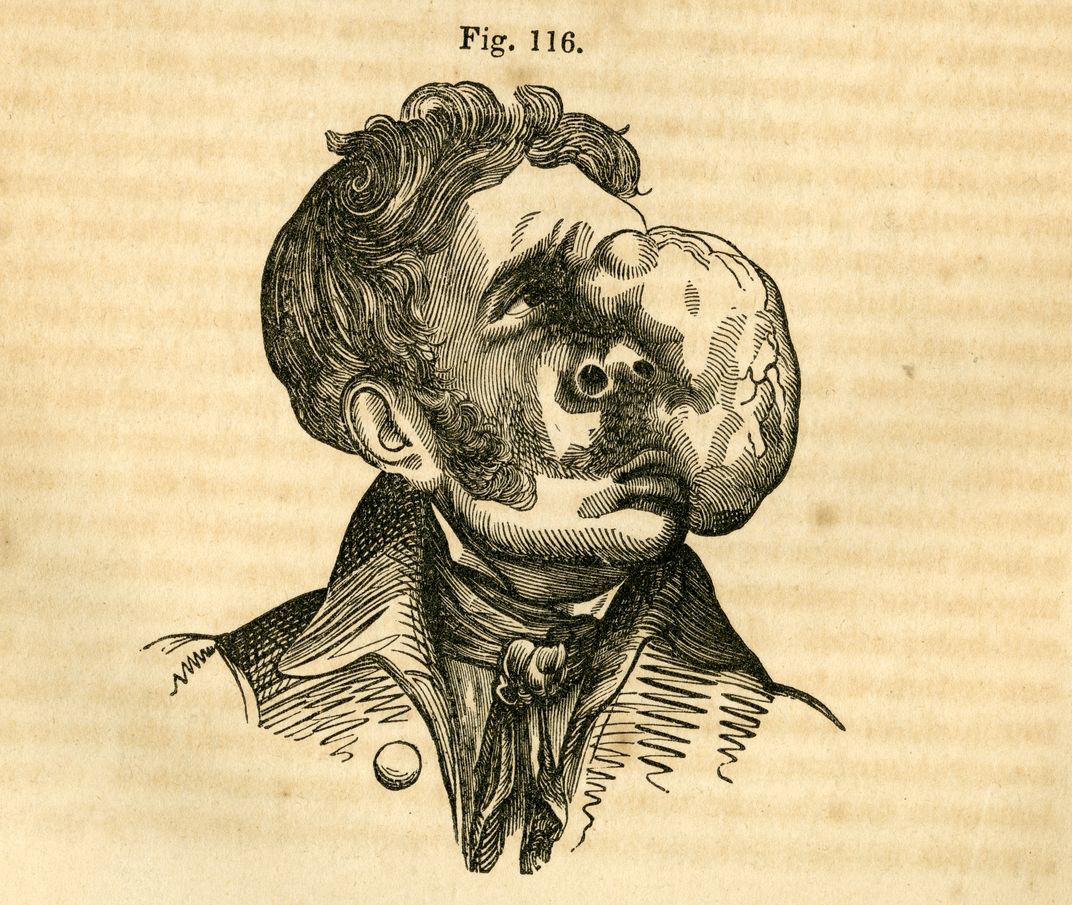

Less happy, however, were Mütter’s students, who grumbled in their seats on surgery day, upset that their own views of the operation might be blocked. After a quick contented survey of the scene, Mütter began the process of tuning them all out so that the entirety of focus could be directed to the patient shaking and drooling in the surgical chair. Nathaniel Dickey was a local Philadelphian whom Mütter had liked from the first time they met: intelligent, funny, and in perfectly good health, aside from the obvious. The 25-year-old’s face was dramatically split down the middle. His lips and the top of his mouth were raw and open, and despite Nathaniel’s best efforts to prevent it, thick cords of spittle often poured from the opening.

It was Nathaniel who sought out Mütter, asking if anything could be done to help a person like him. With a thick slur but bright eyes, he confessed to Mütter how badly he wanted to have a wife and children, how much he dreamed of walking down the street with this beautiful family he so often envisioned having, and have not a single passing stranger gawk at his deformed face. Now, weeks later, Nathaniel sat in front of Mütter, his head firmly supported against the chest of a seated Dr. Norris, and his arms held down against his torso by a tight white sheet.

Mütter had already explained the surgery to Nathaniel in detail. In the days leading up to it, Mütter would thrice daily massage Nathaniel’s face, attempting to desensitize his vulnerable palate. Even the slightest amount of vomit rising from his throat would threaten the entire operation, ruining the delicate work he was attempting to do, and inviting dangerous infection to nest in his already beleaguered mouth. The risk of purging was one of the reasons the surgery had to be performed with the patient almost entirely sober. Mütter also needed him to stay still and stiff, to open his mouth wider and wider if need be, and to keep the contents of a nervous stomach in their place.

Nathaniel had to be more than a patient; he had to be a partner in seeing this difficult surgery to its end. Mütter knew this. And so they would meet multiple times a day for facial massages. And as Mütter’s hands gently explored Nathaniel’s handsome but broken face, he would walk the young man through each moment of the surgery, carefully explaining each danger and tenderly warning of each increasing level of pain. Nathaniel never once wavered in his determination to see it through. But now on the day of the surgery, Mütter saw Nathaniel’s eyes widen and his body become rigid as he moved toward him. Mütter paused for a moment, letting Nathaniel take several deep breaths. Nathaniel’s eyes unconsciously wandered to the table where Mütter had laid out his tools: a knife, a hook, a pair of long forceps, needles, waxed thread, scissors, sponges on handles, wine and water, cold water, towels, and—hidden under a handkerchief for emergency use only—leeches, opiates, and a sharp lancet.

After making his opening remarks, being sure to name and thank each of his impressive assistants, Mütter took care to position himself properly. He decided to stand a little to one side of Nathaniel, to obstruct the entrance of light into the mouth as little as possible. He then asked Nathaniel to throw his head back as far as he could and to open his mouth and keep it in this position as long as he was able. He placed a comforting hand on Nathaniel’s shoulder, squeezed just once, and then began.

Within moments of the surgery’s quick first step—the insertion of a sharp hook into the roof of Nathaniel’s mouth used to gently pull the deformed mass of muscle and skin back—the trio of doctors forgot who they were, or that anyone else was in the room. The students groaned and fussed, as the doctors blocked their view, closing their small circle in an attempt to get a closer look at Mütter’s whirlwind actions. The trick to surgeries of this kind, Mütter knew, was twofold: You had to be quick so as to lessen the stress and pain of the patient, but slow enough to make sure you were doing it right. Mütter’s hands were a confident blur of motion as he cut and pierced, excised and sutured, flayed and positioned.

He checked in with Nathaniel often, offering whatever words of comfort and support he could. And when possible, he tried to involve the doctors who had agreed to assist, but once he realized they were more than content to watch, he focused solely on the job at hand. If Mütter had chosen to look at them, he would have noticed their faces: mouths pursed, eyebrows gathered in concentration, eyes narrowed in half disbelief. Each one wanted to ask Mütter to stop, to slow down. Mütter’s ambidextrousness meant that he could do twice the work in half the time. The doctors grew dizzy and overwhelmed, unsure of which hand to follow, unsure how they would be able to replicate the surgery themselves when it seemed like quick, efficient chaos.

But Mütter paid them no heed. The only thing that could distract him from his work was the face of Nathaniel, which he monitored as a mother would—tracking each wince, each moan, each muffled cry. When Nathaniel’s body would quake uncontrollably under Mütter’s hand, he would remove all instruments and look into Nathaniel’s eyes. With Mütter’s hand gently placed in Nathaniel’s damp hair, he would feed him a small glass of cold water. Nathaniel gargled it, and spat. The pan turned red as it grew slick with blood. And when Nathaniel was ready, Mütter returned to his work, his face calm and focused, clear and bright, almost happy.

After just 25 minutes, it was done. Nathaniel’s face, which just a moment earlier had been an open wound—bleeding, raw, and split—now was tenderly united, the silk thread straining at the incision sites, but holding. Nathaniel, exhausted and drenched in sweat, relaxed into the chair as Mütter walked backward, wiping his hands on a fresh towel. The doctors were silent, still trying to process what they had just seen. The students sat back in their seats, their journals open and empty on their laps. What notes could they take that could capture what they had just witnessed?

It felt as if perhaps they had been given a glimpse of the future, a sign that things were about to change. But Mütter noticed none of it. Instead, he remained focused on Nathaniel. He stepped again toward the trembling young man, a small sponge in hand. He softly blotted the last remnants of blood from his newly reunited mouth, his hand firm and proud on Nathaniel’s shoulder. Where others once saw a monster, Mütter thought, he had revealed the man. And from under the handkerchief on the surgical table, he pulled one more hidden item: a small mirror, clean and shining. With one tender hand cupping the back of his exhausted patient’s head, he held the mirror in front of Nathaniel’s new and handsome face. Mütter smiled. And Nathaniel Dickey, disobeying doctor’s orders this one time, smiled back.

From DR. MÜTTER'S MARVELS: A True Tale of Intrigue and Innovation at the Dawn of Modern Medicine by Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz. Published by arrangement with Gotham Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA), LLC. Copyright © 2014 by Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz.