Documenting the Death of an Assassin

In 1865, a single photograph was taken during the autopsy of John Wilkes Booth. Where is it now?

When President Barack Obama announced this week that he would not release postmortem pictures of Osama bin Laden, people around the world immediately questioned his decision.

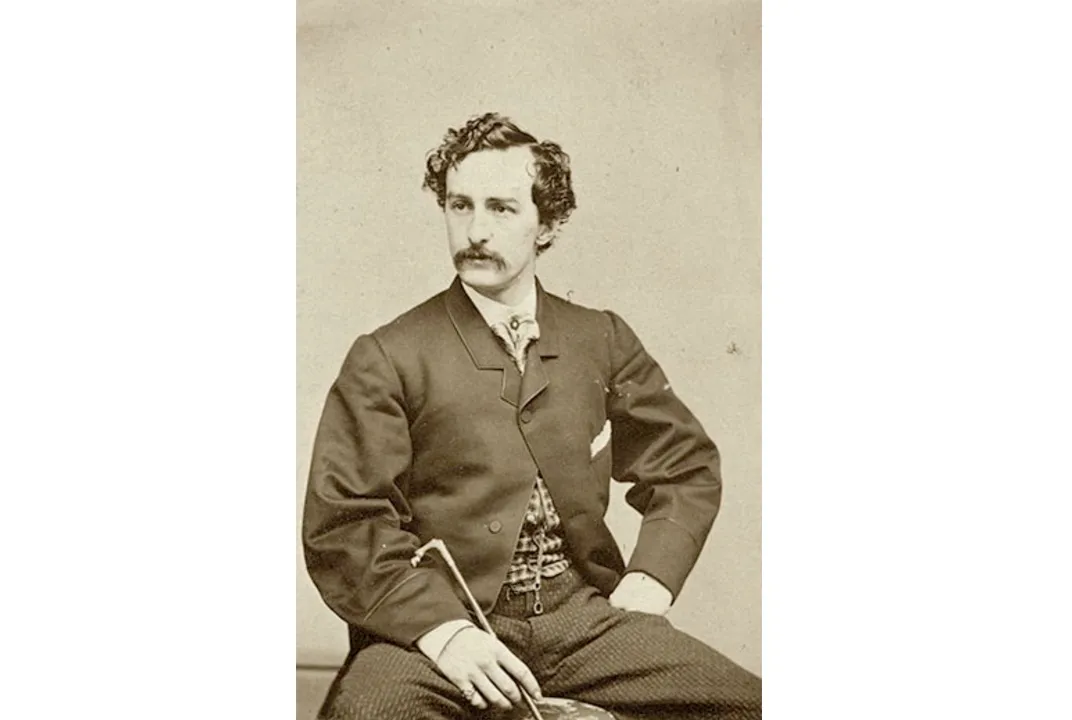

The debate today echoes a similar controversy involving John Wilkes Booth, the man who assassinated President Abraham Lincoln.

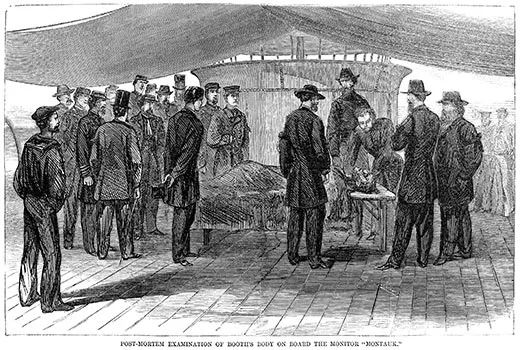

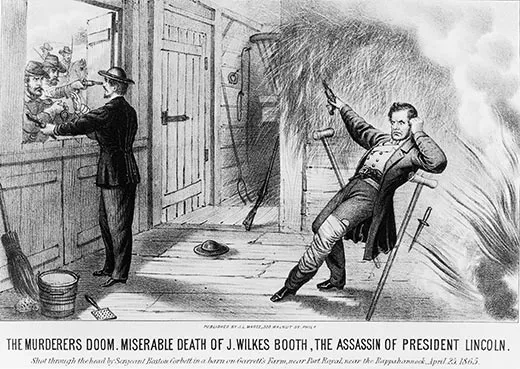

On April 26, 1865—12 days after he shot Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C.—Booth himself was cornered and shot in a Virginia barn. He died from his wound that day. His body was taken back to Washington and then aboard the USS Montauk for an autopsy.

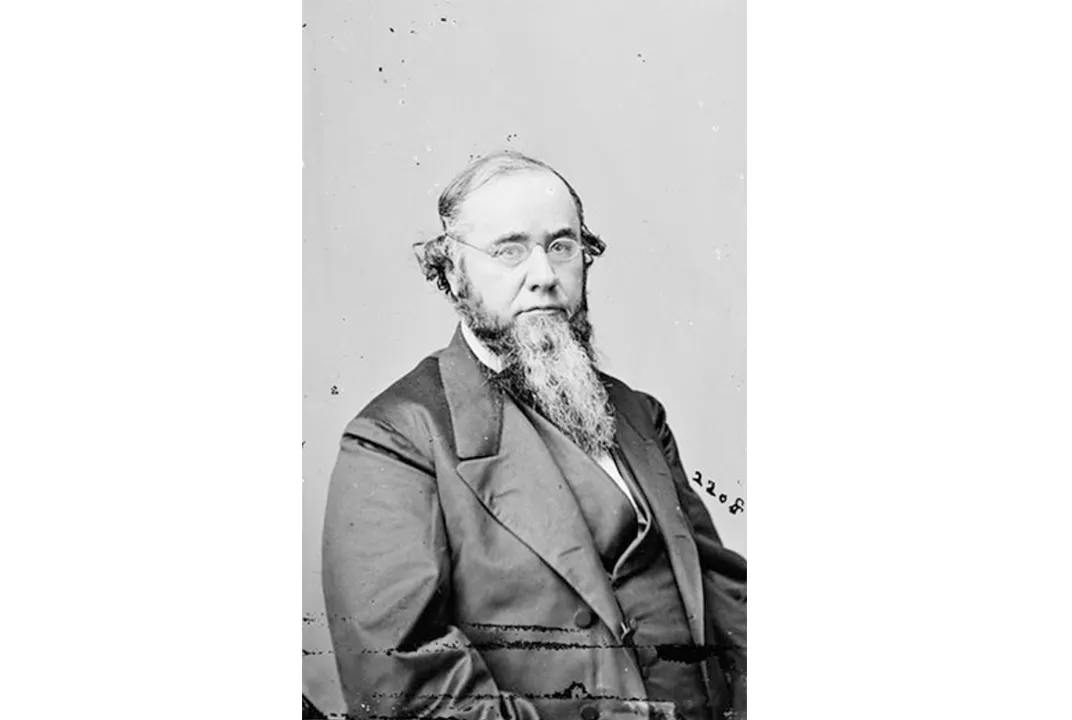

The administration, led by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, ordered that a single photograph be taken of Booth’s corpse, says Bob Zeller, president of the Center for Civil War Photography. On April 27, 1865, many experts agree, famed Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner and his assistant Timothy O’Sullivan took the picture.

It hasn’t been seen since, and its whereabouts are unknown.

“Stanton was a guy who really took charge,” Zeller says. And in this case, Zeller says, he was “trying to control photographs of Booth’s body so he would not be a martyr or lionized.” In the short term, however, the absence of the image buoyed conspiracy theories that Lincoln’s assassin was still alive.

The Booth photo wasn’t the first image that Stanton would have censored. The war secretary was incensed after a photograph of Lincoln’s body in its casket, taken as the slain president lay in Governor’s Room at New York City Hall, was printed in the evening editions of New York newspapers, Zeller writes in The Blue and Gray in Black and White: A History of Civil War Photography.

“I cannot sufficiently express my surprise and disapproval of such an act while the body was in your charge,” Stanton wrote to Gen. Edward D. Townsend, who assisted with Lincoln’s funeral. “...You will direct the provost-marshal to go to the photographer, seize and destroy the plates and any pictures or engravings that may have been made, and consider yourself responsible if the offense is repeated.”

The Booth controversy arose soon afterward, when the New York Tribune reported on April 28 that a photograph of Booth’s body had been taken aboard the Montauk.

A crucial account of what happened while Gardner and O’Sullivan were on the ship, Zeller says, comes from James A. Wardell, a former government detective who had been assigned to accompany the two men. Wardell’s account, given in 1896 to a historian who was searching for the missing Booth photograph, appears in Witness to an Era: The Life and Photographs of Alexander Gardner, by D. Mark Katz:

Under no circumstances was I to allow him or his assistant out of my sight until they had taken a picture and made the print, and then I was to bring the print and the glass [negative] back to the War Department and give it only to Col. [L.C.] Baker [chief of the Secret Service] or Secretary of War Stanton. ...[Gardner] was told that only one plate was to be made and it was to have only one print made and both were to be given to me when finished….

“Gardner took the plate and then gave it to the assistant and told him to take it and develop it and to make one print. I went with him and even went into the dark room. About 4:00 in the afternoon I got the plate and the print from the assistant and took it to the War Department. I went in to the outer office and Col. Baker was just coming out of the War Office. I gave him the plate and print and he stepped to one side and pulled it from the envelope. He looked at it and then dismissed me.

Wardell said he doubted the historian would be able to track down the picture: “The War Department was very determined to make sure that Booth was not made a hero and some rebel would give a good price for one of those pictures of the plate.”

There the trail of the photograph goes cold. But that doesn’t mean it won’t warm up someday, Zeller says.

“That’s the reason why I’m so absolutely passionate about the field of Civil War photography,” he says. “You keep making huge finds. You can’t say it won’t happen. You can’t even say that it’s not sitting ... in the National Archives War Department records.”

Edward McCarter, supervisor of the still photography collection at the National Archives, says the photo is not there, as far as he knows. He’d never even heard of such a photograph—and given how often and how long researchers have been using the photographs and textual records in the Archives, “I’m sure it would have surfaced.”