Digging into a Historic Rivalry

As archaeologists unearth a secret slave passageway used by abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens, scholars reevaluate his reputation and that of James Buchanan

When, in 2002, archaeologists Mary Ann Levine and James Delle’s crew of student excavators broke through the roof of an old cistern in the courtyard of a house belonging to one of 19th-century America’s most important politicians, they discovered something totally unexpected: a secret hiding place for runaway slaves. Although the saga of American slavery, and the Underground Railroad (the network that helped fugitives make their way north to freedom), is replete with legends of ingeniously concealed hideaways, secret redoubts such as Thaddeus Stevens’ in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, are actually quite rare. “I’ve looked at many tunnels that were alleged to have been used by the Underground Railroad,” says Delle, 40, a professor at nearby KutztownUniversity. (Levine is on the faculty at Franklin & MarshallCollege.) “Usually I’m debunking these sites. But in this case, I can think of no other possible explanation.”

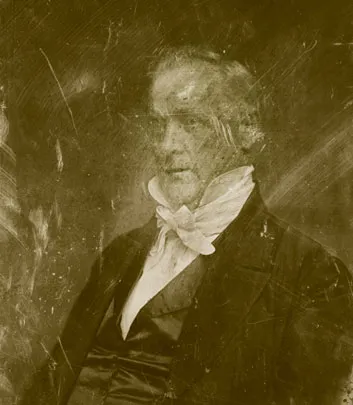

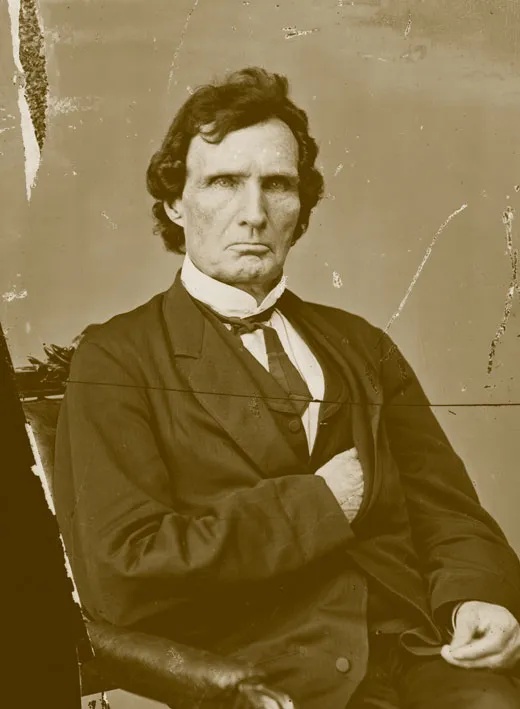

In the mid-1800s, Stevens, a seven-term congressman and power broker, had been a household name, renowned, and in many cases, reviled for his eloquent calls for the abolition of slavery. A brilliant lawyer with a commitment to racial equality far in advance of his time, he would be the father of two amendments to the Constitution—the 14th, guaranteeing all citizens equal protection before the law, and the 15th, granting freedmen the right to vote—and also an architect of Reconstruction. Alightning rod for the political passions that electrified the United States during and after the Civil War, he is virtually unknown today, nearly a century and a half after his death in 1868. “If you stopped a hundred people on the street today, right here in Lancaster, and asked them who Stevens was, I bet only 50 would know,” says Lancaster’s mayor, Charlie Smithgall, 58. “And most of them could tell you only that there’s a junior college here that has his name on it.”

Stevens’ reputation, even in his hometown, is dwarfed by that of his neighbor and bitter rival, James Buchanan, the nation’s 15th president and arguably its worst. “Buchanan’s vision was cemented in the past,” says Jean Harvey Baker, a historian at GoucherCollege, in Baltimore, Maryland, and the author of a biography of Buchanan to be published in May. “He continued to see the United States as a slaveholding republic at a time when other Western countries were moving away from slavery. If he could have, he would have made the United States into a slave society that extended from Baja California to the East Coast.” Today, Buchanan’s stately Lancaster home, Wheatland, stands as a lovingly restored memorial; Stevens’ modest brick row house has lain largely neglected for decades and, despite the historic archaeological find, will soon be partially demolished to make way for a massive new convention center.

The two men could hardly have produced a more vivid study in contrasts: one was a firebrand abolitionist, considered the foremost radical of his generation, the other a Northerner who supported the South—in the parlance of the time, a doughface. “Doughfaces were mainly border-state congressmen who did the political bidding of the South,” says Baker. “The term implied that they were malleable, that they could be worked on. They didn’t give a damn about slavery. They cared only about keeping intact the Democratic Party’s coalition with the South.” Stevens was a man driven by deeply held moral convictions. Buchanan, on the other hand, emerged as the great equivocator—eternally placating, legalistic and so priggish that President Andrew Jackson once dismissed him as a “Miss Nancy”—a sissy.

Yet the lives of Stevens and Buchanan maintained curiously parallel courses. Both men rose from humble origins: Buchanan was born in a log cabin on the Pennsylvania frontier in 1791, and Stevens a year later in rural Vermont. Both were lifelong bachelors and workaholics, fueled by intense political ambition. Both were lawyers wh0 built their careers in Lancaster; they lived less than two miles apart. And both would die in the summer of 1868 amid the postwar trauma of Reconstruction. For decades, in an age when slavery was a 600-pound gorilla in the parlor of American democracy, the two men would find their bitterly opposed political viewpoints inextricably entwined. Buchanan would lead the United States to the brink of Civil War. Stevens would shape its aftermath.

Lancaster was a prosperous little city with a population of about 6,000 when Buchanan, at age 18, arrived there in 1809. Handsome two- and three-story brick and fieldstone houses were laid out in a dignified grid, befitting an urban center that had served as the state’s capital since 1799.

Home to gunsmiths, artisans and markets for the hundreds of farmers who lived in the surrounding county, Lancaster exuded an atmosphere of bustle and importance, even though its streets were unpaved. Fresh out of DickinsonCollege in Carlisle, Buchanan was determined to please his demanding Scots-Irish father, who never tired of telling his firstborn son how much he had sacrificed to educate him.

Had Buchanan lived in present times, pundits would likely describe him as an inside-the-Beltway type, a professional politician who advances himself through appointed positions and personal connections. “In the 18th century, ambitious men went into the church,” says Baker. “In the 20th, they went into big business. The way you made a mark in Buchanan’s era was not by creating an Enron but by entering party politics.”

Buchanan, tall and ruggedly handsome, entered Congress as a Federalist in 1821, representing Lancaster and the surrounding region. By this time, the Federalist Party, founded by Alexander Hamilton, had declined as a national force, a result both of its opposition to the War of 1812 and its image as a protector of the wealthy. The party had lost ground to Democrats, who traced their origins to Thomas Jefferson and presented themselves as champions of the common man. The new Federalist congressman’s primary loyalty, however, was less to party than to career. “Buchanan was an opportunist,” says historian Matthew Pinsker of DickinsonCollege. “Early on, he learned an important lesson for a man who wanted to get ahead in politics: don’t disagree with anyone. He had an impressive résumé, but he was not a popular figure; he was an insider.”

In 1828, sensing the rise of a vigorous opposition party, Buchanan threw his support to Democrat Andrew Jackson, who was elected president that year. Buchanan served the last of his five terms in the House of Representatives as a Democrat. After a stint as Jackson’s ambassador to Russia from 1832 to 1833, he was elected to the Senate (by the State Legislature, in accordance with the laws of that time) in 1834. Eleven years later, when Democrat James Polk became president, Buchanan served as his Secretary of State. He won plaudits for his advancement of American claims in the Northwest.

Buchanan was already a rising political star by the time 50-year-old Thaddeus Stevens moved to Lancaster in 1842. Stevens had come to Pennsylvania after graduating from Dartmouth College; he settled in Gettysburg, where he earned a reputation as the most brilliant lawyer in town, despite dual disabilities: a clubbed foot and a disfiguring illness—alopecia, a rare form of baldness—that caused him to lose his hair by age 35. (He wore a wig throughout his career; when a political admirer once begged for a lock of his hair, he plucked off the entire hairpiece and presented it to her with a rueful smile.)

Stevens had won election to the Pennsylvania Legislature in 1833 at age 41. In office, he emerged as an advocate for public education. His preoccupation, however, was slavery. His hatred of it was rooted not only in his Yankee upbringing but also in an 1821 incident. In a case he would thereafter never explain or even allude to, Stevens successfully defended a Maryland owner of runaway slave Charity Butler, who was consequently returned to bondage. Though a professional triumph, the case “affected him deeply,” says Hans Trefousse, author of Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth-Century Egalitarian and professor emeritus of American history at the City University of New York. “I think that he was disgusted with himself for what he had done.” From then on, Stevens’ commitment to equal rights for African-Americans—an idea that was anathema even to many abolitionists—would be unwavering.

In contrast, Buchanan condemned slavery in the abstract while supporting it in fact. It was, he asserted before Congress in 1826, “one of those moral evils from which it is impossible for us to escape without the introduction of evils infinitely greater. There are portions of this Union in which, if you emancipate your slaves, they will become masters.” He proclaimed a willingness to “bundle on my knapsack” and spring to the South’s defense, should that ever become necessary, and vigorously defended the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which required citizens, regardless of their beliefs, to help recapture runaway slaves anywhere in the country. Says Baker: “He was totally opposed to abolitionism, and pro-Southern. He wanted to protect the Union as it was, run by a Southern minority. His agenda was appeasement.”

Even so, Buchanan is not without his defenders. “Buchanan revered the Constitution with an almost religious fervor,” says Samuel C. Slaymaker, director of the James Buchanan Foundation, which oversees Wheatland. “He was afraid of the masses, but he was also afraid of the presidency becoming too powerful. He saw the president as an administrator for the laws that Congress made, not as someone who was there to make the law himself. He foresaw that a war would be long and bloody, and feared that the country might not survive it.” As for slavery, Slaymaker says Buchanan thought it more a legal than a moral issue and believed it would fade out in the South as it had in Pennsylvania. He felt that the abolitionists only made things worse by provoking Southerners with their “immoderate language.”

Although Buchanan had long dreamed of becoming president, by the time he was appointed to yet another diplomatic post, at 62, as minister to England under President Franklin Pierce in 1853, he believed that his career was effectively over. Ironically, this exile helped him secure the very prize he had sought. During his three years abroad, most nationally known Democrats—including Pierce and Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois—were tarnished by bitter infighting over whether slavery should be extended to the Western territories. Within months of his return home, Buchanan emerged as his party’s presidential candidate in 1856.

During the campaign, Buchanan delivered no speeches at all, which was customary at the time. Nevertheless, his opponents mocked his silence and his lackluster performance. “There is a wrong impression about one of the candidates,” Stevens declared of his fellow Lancastrian. “There is no such person running as James Buchanan. He is dead of lockjaw. Nothing remains but a platform and a bloated mass of political putridity.” The Republicans, who had established their party only two years earlier, nominated John C. Frémont, a mapmaker and explorer who had led several expeditions across the Rockies in the 1840s.

But the well-established and better-funded Democrats, who pandered to proslavery Southerners, had the edge, and Buchanan, silent to the end, captured the presidency with 45 percent of the vote. (With antislavery Northerners flocking to the Republicans, the new party made a startlingly strong showing, with 33 percent of the vote.)

buchanan’s inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1857, reflected an almost pathological complacency. “Everything of a practical nature has been decided,” he declared. “No other question remains for adjustment, because all agree that under the Constitution slavery in the States is beyond the reach of any human power except that of the respective States themselves wherein it exists.” The new president was, of course, in deep denial. Since 1855, bloody conflict between proslavery and antislavery forces had ravaged the Kansas Territory; the violence had reached a crescendo during the campaign that led to Buchanan’s election.

While Buchanan temporized, Stevens was living a double life, as a prominent lawyer and politician—and as a clandestine activist. His fierce abolitionist views were well known, but the extent of his secret work on behalf of fugitive slaves is only now becoming clear. Even when Stevens lived in Gettysburg, he had begun to volunteer his time to defend runaway slaves in court. After his move to Lancaster in 1842, he regularly aided fugitives traveling from the city of Columbia, Pennsylvania, a key center of Underground Railroad activity 14 miles to the west. Stevens also paid a spy to report on slave catchers active in the area, passing on what he learned to fugitives. “I have a spy on the spies and thus ascertain the facts,” he wrote to his fellow abolitionist, Jeremiah Brown, in 1847. “All this, however, must remain secret or we will lose all the advantages we now have. These are the eighth set of slaves I have warned within a week.”

No surviving documents describe just how the cistern behind Stevens’ brick house functioned as a hiding place. Perhaps fugitives arrived in Lancaster from Columbia, where an African-American lumber merchant, William Whipper, shipped them eastward toward Philadelphia and to freedom on railroad freight cars fitted with secret compartments. The fugitives might then have been delivered, sealed into barrels, to the tavern next to Stevens’ house. Slaves may have been hidden in the cistern for a few hours, or days, until they could be passed on to other locations.

In 1848, Stevens entered into a partnership with a 35-year old widow, Lydia Hamilton Smith, a light-skinned mulatto (her father was white) who would act for the next 25 years as his housekeeper, property manager and confidante. It was a remarkable—and courageous—relationship in an era when segregation was virtually universal. Even in the North, blacks were almost completely excluded from colleges and public schools and barred from theaters, libraries, eating places and accommodations. Silk merchant Lewis Tappan, the most influential abolitionist in New York City during the antebellum period, declined to hire black clerks in his store because he considered them untrustworthy. Genuine partnerships between whites and blacks were almost unheard of.

It is likely, given her connections in the local African-American community, that Smith managed the movement of fugitives in and out of the Stevens house. Able to shuttle easily between the divided worlds of black and white, she was ideally suited for such a mission. While it was widely rumored in Stevens’ lifetime and afterward that the two were lovers, no hard evidence exists to support that claim. Stevens, in any case, treated Smith as his equal. He addressed her as “Madam,” invariably offered her his seat on public transportation and included her in social occasions with his friends.

Southern politicians had warned that they would lead their states out of the Union if Abraham Lincoln, the Republican candidate for president, won. In the election, opposition to him split among two Democrats, Stephen A. Douglas and John C. Breckinridge, and a fourth candidate, John Bell. Lincoln was elected in November 1860. No sooner had the race been decided than the Southern states began to make good on their threats. In the months leading up to Lincoln’s inauguration, a forceful response from President Buchanan might have dampened the secession ardor. But he responded with characteristic equivocation. On December 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded; ten other Southern states followed. “Buchanan handled secession abysmally,” says historian Baker. “When South Carolina seceded, he tried to do all he could for the Southerners. He retained Southern cabinet officers who were, in effect, agents of the South and who continued to influence him in ways that were pretty close to treasonous. He spent so much time on details that the larger issues escaped him. When things got tough, he got immobilized.”

Even when members of his cabinet began resigning to join the embryonic Confederacy, Buchanan focused on his pet project, a plan to purchase Cuba from Spain. “A president with vision would have looked ahead and begun the process of returning the Army to the East Coast from the West, where it was scattered on remote posts,” says Baker. “But he did nothing. He had also sent a huge naval expedition to Paraguay, of all places, so that when he needed the Navy, he didn’t have it either.” Yankees derided him as a Southern toady, while Confederates blamed him for not facilitating their secession from the Union. As a private citizen in Lancaster in 1861, he proclaimed his support for a Northern victory. But by then almost no one was listening.

When Buchanan died, on June 1, 1868, seven years after leaving office (and three years after the end of the Civil War), the New York Times appraised him harshly: “He met the crisis of secession in a timid and vacillating spirit, temporizing with both parties, and studiously avoiding the adoption of a decided policy,” the paper’s obituary writer concluded. “To every appeal from the loyal men of the country for an energetic and patriotic opposition to the plots of the Secessionists, his only reply was: ‘The South has no right to secede, but I have no power to prevent them.’ ” By the time Lincoln took the oath of office, the obituary continued, Buchanan had “retired to the privacy of his home in Wheatland, followed by the ill-will of every section of the country.”

having served in Congress from 1849 to 1853, Thaddeus Stevens had been reelected in 1858 after a nearly six-year hiatus. Stevens saw the Civil War as an opportunity to end slavery once and for all, and as the war loomed, he approached the zenith of his power. Although he considered Lincoln too willing to compromise on the matter of race, Stevens, in his capacity as chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, acted as a key backer of the administration and the war effort. In December 1861, more than a year before Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation (which freed only those slaves in Rebel territory), he called for the enactment of abolition.

Once peace was declared, on April 9, 1865—and in the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination less than a week later—Stevens understood immediately that former slaves could exercise their new freedoms only with the support of the federal government, and even, of federal troops. “He believed that he was living at a revolutionary moment,” says Eric Foner, author of Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 and a professor of history at ColumbiaUniversity. “The Civil War had shattered the institutions of Southern society. Stevens wanted not just reunion of the states, but to remake Southern society completely. He wanted to take the land away from the wealthy planter class, and to give it to blacks, and to reshape the South in the image of the North, as a land of small farmers, political democracy, and public schools, and with the principle of racial equality engraved in it. Stevens was also very old, and he knew that if he was ever going to accomplish anything of what he wanted, it had to be now.”

By 1866, with two years left to live, and in almost constant pain from a variety of ailments, the 74-year-old Stevens was also pressing aggressively in Congress for a new amendment to the Constitution that would require states to afford their citizens equal protection under the law, without regard to race. After several months’ debate, Congress passed the 14th Amendment in June 1866. (It would be ratified by the states in 1868.) The legislation was not as far-reaching as Stevens had hoped; in particular, it did not include a provision to grant freedmen the vote. Nevertheless, in a speech he delivered before Congress shortly after the bill’s passage, Stevens demonstrated a willingness to accept compromise: “Do you inquire why . . . I accept so imperfect a proposition? . . . Because I live among men and not among angels.”

Despite his attempt to create a legislative solution, Stevens watched as Lincoln’s successor, Tennessean Andrew Johnson, permitted Southern state assemblies, which included many former Confederates, to enact laws that effectively denied freedmen their civil and economic rights. Anti-black rioting swept Southern cities, leaving hundreds of African-Americans dead. “There was violence all over the place,” says Foner. “Law and order had broken down everywhere. The failure of the first phase of Reconstruction discredited President Johnson and opened the door to men like Stevens. The Radicals [Stevens’ wing of the Republican Party] were at least seen to have a coherent agenda.” Stevens saw his opportunity: enfeebled though he was by age and illness, he redoubled efforts to block the rising power of defeated Confederates.

By early 1867, so weak that he could deliver speeches only in a whisper, Stevens pleaded with Congress to act, even as his colleagues had to crowd around him in order to hear. “The South,” he charged, “is covered all over with anarchy and murder.” It is said that the oration was one of the few in Congress that resulted in the changing of votes on the spot. Stevens got what he wanted: more federal troops would be dispatched to the South, eventually to become an army of occupation 20,000 strong to protect the rights of freedmen and of whites loyal to the Union.

Stevens also continued to argue forcefully in Congress that blacks everywhere must have the vote, still denied them even in some Northern states. “We have imposed upon them the privilege of fighting our battles, of dying in defense of freedom, and of bearing their equal portion of taxes; but where have we given them the privilege of ever participating in the formation of the laws for the government of their native land?”

It was also Stevens, in his final battle in 1868, who led the attempt to impeach Johnson for firing a Radical member of his cabinet, though the real issue was whether the Congress or the president would determine the course of Reconstruction policy. As personally unpopular as the president was, many members of Congress felt that this time Stevens and the Radicals had overreached in their attempt to reduce the power of the executive branch. When the heads were counted in the Senate that May, the effort to oust the president failed by a single vote.

Stevens died a few months later, on August 12, 1868. In the years immediately preceding the war, he had been vilified for views considered outside the national mainstream. But he lived long enough to see at least some of his ideals enacted into law. “Stevens was ahead of his time because he truly believed in racial equality,” says Trefousse. “Without him, the 14th Amendment, and the 15th Amendment, guaranteeing suffrage to the freedmen, would have been impossible.” (Stevens did not live to see ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870.) Says Trefousse: “In practice, those amendments were effectively nullified in the South in the years after the end of Reconstruction. But they were still in the law. In the 20th century, the amendments would remind Americans of what those laws had once stood for: they were the standard that the nation had set for itself.” In fact, the 14th and 15th amendments became the foundation upon which virtually all 20th-century civil rights legislation would be built.

The North had won the Civil War on the battlefield; in some respects, however, the victory was short-lived. By 1877, federal troops had withdrawn completely from the South. Stevens’ amendments had, in essence, been dismantled, and harsh discriminatory laws had been enacted. Vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan terrorized blacks. The South, and indeed most of the nation, slumped into almost a century of institutionalized segregation.

As for Stevens, perhaps the nadir in his reputation was reached in 1915 with the appearance of movie director D.W. Griffith’s Civil War epic, The Birth of A Nation, in which he was portrayed as a villain, plotting with a mixed-race co-conspirator to instigate a race war against whites. Smith appears in the film as well, referred to disparagingly as “the mulatto,” and characterized as ambitious and grasping. The film calls the Ku Klux Klan “the organization that saved the South from the anarchy of black rule.” President Woodrow Wilson allowed the movie, which portrays blacks as clownish, lascivious lowlifes, to premier at the White House.

As Stevens’ reputation plummeted, James Buchanan’s began to rise, at least in Lancaster. During the 1930s, Wheatland was restored, with the support of public donations, to its mid-19thcentury splendor. (Stevens’ home was not even included on a 1962 map of the Lancaster Historical Society’s important downtown sites.) On a recent tour of Wheatland, a docent, costumed in period dress, cheerily described Buchanan as “a nice man who just believed in the Constitution.” Stevens, she volunteered, seemed to have had an inexplicable mean streak, adding, “I don’t really know exactly what his problem was.”

Later, as snowflakes swirled in the streets of Lancaster, archaeologist Jim Delle unlocked the front door of the row house where Stevens lived, only a block from the square where crowds of spellbound supporters had once listened to his surging oratory. The Federal-era facade has disappeared under a modern facing of dingy white bricks; a garage door intrudes on Stevens’ front parlor. Moldering industrial carpeting, cracked plaster and graffiti lent an atmosphere of desolation to the ground-floor room where Stevens likely wrote his most famous speeches. In the courtyard behind the house, Delle scraped snow off a sheet of plywood covering the broken crown of the cistern; we climbed down an aluminum ladder. In the dank brick compartment, the archaeologist pointed out a small aperture through which fugitives had entered, crawling from a tunnel that connected to the basement of the tavern next door.

Two years ago, real estate developers agreed, after considerable local protests, to leave about half of Stevens’ house standing; however, they insist that the rest of the building must be leveled to make room for a new convention center. “We have to be efficient from a cost standpoint,” says David Hixson of the Convention Center Authority. “But we are making an effort to integrate the historic structures into the project. We need that space.” Current plans, yet unfunded, call for the remaining section of the house to be restored; an underground museum, incorporating the cistern, would also be built. “We can’t just walk away from this house,” says Randolph Harris, the former director of the Historic Preservation Trust of Lancaster County, who has fought to prevent the demolition of Stevens’ house and his adjoining properties. “Stevens is way too important a figure in our history to abandon once again.”