Dancing for Mao

A photograph of a 5-year-old girl made her famous in China—and haunted the man who took it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Kang-Wenjie-Loyalty-Dance-Li-Zhensheng-631.jpg)

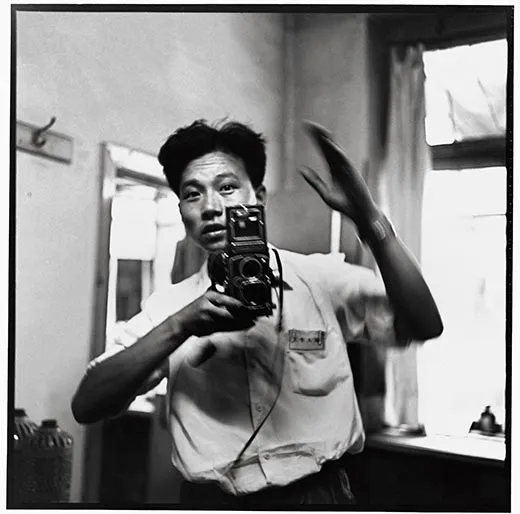

Li Zhensheng heard singing followed by a burst of applause. Following the sounds led the photojournalist to a young girl with unusually fair hair tied in ponytails, dancing with her arms upraised and surrounded by smiling, clapping soldiers.

They were at the Red Guard Stadium in Harbin, in northern China, along with hundreds of thousands of Communist Party cadres, workers, peasants and other soldiers who had gathered for a marathon conference on the teachings of Chairman Mao Zedong. This was 1968, nearly two years into the Cultural Revolution, Mao's attempt to purge Chinese society of supposed bourgeois elements and escalate his own cult of personality. The conferees seemed to be trying to outdo one another in their professions of love for their nation's leader.

On April 28, the last day of the 23-day gathering, a 5-year-old kindergartner was performing the "loyalty dance," as it was known. In front of the soldiers in the stadium stands, she skipped in place and sang:

No matter how close our parents are to us, they are

not as close as our relationship with Mao

How absurd, thought Li, who was then a photographer for the Heilongjiang Daily, a party newspaper. The girl certainly was lovely and eager to please, but the photojournalist found the excess of zeal discomforting. "They had to love him to the extreme," says Li, now 68 and retired.

In the cult of Mao, everyone was expected to perform the loyalty dance—from miners to office workers to toddlers to old ladies whose feet had been bound. "The movements were always toward the sky—that way you could show how respectful you were to Mao," Li says. "Everyone knew how to dance it."

Li shot six photographs of the scene, of which the Heilongjiang Daily published two. When the girl—instantly known as "Little Yellow Hair"—returned home to Dedu County (now Wudalianchi City), people came to the roadside to cheer her for bringing fame and honor to their town.

Li kept on taking pictures—including those he called his "negative negatives": Red Guards shaving the head of a provincial governor because his hairline was too similar to Mao's; security forces shooting, point-blank, two accused counterrevolutionaries for publishing a flier the government deemed too pro-Soviet. These were scenes that China did not want the rest of the world—or, for that matter, its own people—to see.

In the darkroom, Li would separate potentially dangerous negatives and hide them in his desk. When the time seemed right he would take them home for safer keeping, having cut a hiding space the size of a book in the floorboards of his one-room apartment.

Even after the Cultural Revolution effectively ended with Mao's death, at age 82, in 1976, Li was wary about showing his more incendiary work. In 1980 he left the newspaper to teach at Beijing University's International Political Science Institute. In 1988, the organizers of a nationwide photography competition—what Li says was China's first such undertaking as it opened up to the outside world—encouraged him to enter some of his pictures.

Then-Defense Minister Zhang Aiping, who had been imprisoned for years during the Cultural Revolution, greeted the exhibition with the remark, "Let history tell the future." Li's pictures (which did not include "Little Yellow Hair") won the grand prize.

"The authorities were shocked by the violence depicted in Li's images of public humiliations inflicted upon dignitaries and by the photographs of the executions," says Robert Pledge, co-founder of New York City photo agency Contact Press Images, which would collaborate with Li in publishing his life's work in the book Red-Color News Soldier. (Images from the book have been shown in ten countries, with exhibits scheduled for Hungary, Australia and Singapore later this year.)

For his part, Li says he remained haunted by the people in his photographs. He wanted to know what had become of those who had survived; he wanted to connect with the families of those who hadn't. In 1998, he wrote an article for his former newspaper under the headline, "Where Are You, Little Girl Who Performed the Loyalty Dance?"

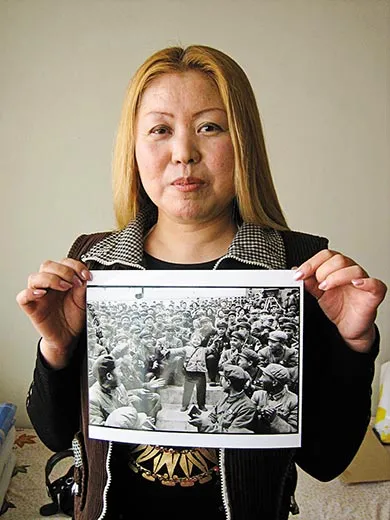

A week later, he heard from Kang Wenjie.

Kang still lived in Wudalianchi City, not far from the Russian border. She made a living selling wholesale clothes to Russian traders. She was married and had a 12-year-old son.

Kang told Li she had been picked to represent her city those many years ago because she could sing and dance, but she hadn't even known that the dance she performed that day had a name. After Li told her about it, she used the very word in her reaction that he had thought in 1968: ke xiao—absurd. "I was merely a naive child who knew nothing," Kang, now 46, says today. "How could I become that well known after a dance?"

Li says the story reminds him of the fable of the naked emperor's new clothes—here was a child who couldn't even read Mao's writings being held up as a model of Maoist thought. "During the Cultural Revolution," Li says, "no one dared to tell the truth."

Even today, the truth about those dark days remains a delicate subject. Li's book has been published in six languages, but it is not available in China.

Jennifer Lin covered China from 1996 to 1999 for the Philadelphia Inquirer, where she remains a reporter.