Chasing the Lydian Hoard

Author Sharon Waxman digs into the tangle over looted artifacts between the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Turkish government

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/loot_631.jpg)

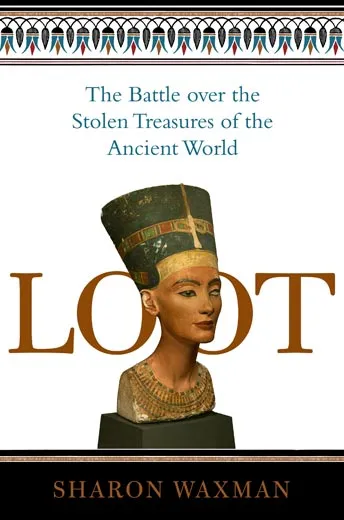

In her new book, “LOOT: The Battle over the Stolen Treasures of the Ancient World,” Sharon Waxman, a former culture reporter for the New York Times and longtime foreign correspondent, gives readers a behind-the-scenes view of the high-stakes, high-powered conflict over who should own the world’s great works of ancient art. Traveling the globe, Waxman met with museum directors, curators, government officials, dealers and journalists to unravel the cultural politics of where antiquities ought to be kept. In the following excerpt from the chapter titled “Chasing the Lydian Hoard,” Waxman tracks a Turkish journalist’s dogged quest for the return of looted artifacts, the ultimate outcome of that quest and its consequences.

Chapter 6 Excerpt

Özgen Acar had been a reporter for Cumhuriyet, Turkey’s oldest daily newspaper, for a decade when, in 1970, he received a visit from Peter Hopkirk, a British journalist from the Sunday Times of London.

“I’m chasing a treasure,” Hopkirk told Acar, intriguingly. “It’s been smuggled out of Turkey. A U.S. museum bought it, and it’s a big secret.”

Acar had grown up in Izmir, on the western coast of Turkey, and had an early taste of antiquities when his mother, an elementary school teacher, took him to museums and to the sites of the ancient Greek origins of his native city. In 1963 he traveled with his backpack along the Turkish coastline, discovering the cultural riches there. But his abiding interest was current affairs, and he had studied political science and economics before getting his first job as a journalist.

Nonetheless, he was intrigued by Hopkirk’s call. Earlier that year, American journalists had gotten a whiff of a brewing scandal at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The Boston Globe had written about a set of golden treasures acquired controversially by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and in doing so mentioned a “Lydian hoard” taken from tombs near Sardis, in Turkey’s Hermus river valley, that was being held in secret by the Met. In August 1970 the New York Times printed a dispatch from the Times of London in which Turkey officially asked for details about the alleged illegal export, warning that it would bar foreign archaeologists from any country that did not return smuggled treasures. Theodore Rousseau, the Met’s chief curator, denied that the museum had exported anything illegally, but added, mysteriously, that there “seemed to be hearsay fabricated around something that might have a kernel of truth to it.”

Hopkirk, the British journalist, was looking to break the story, but he needed a Turkish partner to help him chase the trail locally. He offered Acar the opportunity to team up and investigate and publish simultaneously in both papers. Acar grabbed what seemed like a good story.

They chased the clues that Hopkirk had from his sources: a group of hundreds of golden pieces—coins and jewelry and household goods—had been found near Usak, in southwestern Turkey. Usak was the closest population center to what had been the heart of the kingdom of Lydia in the sixth century BC. The trove had been bought by the Met, which knew that the pieces had no known origin, or provenance, and was keeping the pieces in its storerooms. Acar traveled to Usak, a small town where the residents said no one had heard of a recently discovered golden hoard. He also went to New York City and visited the Met. He called the Ancient Near East department and spoke to the curator, Oscar White Muscarella. Muscarella told him there was nothing like what he described in his department.

In the end, the journalists couldn’t produce anything definitive. Hopkirk was frustrated, but Acar was intrigued; why, he wondered, did a British journalist care so much about ancient pieces from Turkey anyway? He began to consider the issue from a different perspective, as a problem that affected world culture and human history, not just Turkish history. No one, he decided, has the right to smuggle antiquities. As he continued his research, he became more convinced of this, and angrier at those who had irretrievably damaged a tangible link to the past.

For 16 years, Acar didn’t publish a thing about the Lydian treasures. But he continued to work on the story in his spare time. As 1970 gave way to 1971 and 1972, he traveled to Usak once every five or six months, making the six-hour journey to the small town by bus. He asked if anyone had heard about digs in the tumuli outside of town, but no one said they had, at least initially. But as two years became three, and three years became five, six, and eight, Acar became a familiar face in the village. Sources began to crack. He would hear the grumbling, here and there, from people who had missed out on the windfall, about others who had been paid for digging in the tumuli. He conducted re-search about the Lydian kingdom, whose capital was in Sardis and whose borders stretched from the Aegean Sea to the Persian frontier. The greatest of the Lydian kings, Croesus, was renowned for his vast treasures of gold and silver. His name became synonymous in the West with the measure of extreme wealth—“as rich as Croesus.” By some accounts Croesus was the first ruler to mint coins, and he filled the Lydian treasury with his wealth. He ordered the construction of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. But he was also the last king of Lydia. In 547 BC, Croesus was toppled by King Cyrus of Persia, who reduced the Lydian kingdom to a distant outpost of his empire.

Convinced that the Met possessed the Lydian hoard but was refusing to acknowledge it, Acar continued his investigation year after year, visiting Usak and, when he could, questioning the Met. (In Turkey, the hoard became known as “the Karun treasures,” as Karun is the Arabic and Persian rendition of Croesus.) Acar became known in Usak for opposing the looting of Turkey’s cultural patrimony, and on one visit he was talking to some villagers in a café when one called him into the street to speak privately. “There are six or seven of us going to rob one of the tumuli,” the villager told him. “But my heart isn’t in it.” He gave Acar the name of the place and asked him to inform the local officials. Acar did. One of those officials was Kazim Akbiyikoglu, a local archaeologist and the curator of the Usak museum. The police assigned Akbiyikoglu to excavate there instead. He discovered a cache of treasures from the Phrygian kingdom, a civilization that followed the Lydians.

In New York, where the Met had muffled the initial rumors about a spectacular, possibly illegal, purchase, more rumors emerged in 1973. This time, the museum quietly leaked a story to the New York Times about the acquisition of 219 Greek gold and silver pieces, still being held in storage. The Times’s art critic John Canaday noted that the treasures dated to the sixth century B.C. and had reportedly been bought for about $500,000 by the Madison Avenue dealer John J. Klejman and sold to the museum in 1966, 1967, and 1968.The New York Post weighed in at this time, too, and asked Dietrich von Bothmer, the curator of the Greek and Roman department (where the pieces were kept), where the treasures came from. “You should ask Mr. J. J. Klejman that,” retorted von Bothmer. A few pieces from the collection had been shown the previous year in a survey exhibit, but the objects were not published in the catalog and remained in the museum’s storerooms. The director of the Met, Thomas Hoving, and von Bothmer believed that the museum had no obligation to determine whether the objects had been looted. The acquisition predated the UNESCO agreement of 1970, which banned the illegal export and transfer of cultural property, and both Klejman and the museum justified the purchase under the rules of the old code, whereby works whose provenance could not be specifically demonstrated as illegal could be legitimately purchased and sold.

Turkey, they would soon learn, felt differently.

Özgen Acar did not see the New York Times article, and anyway, he was looking for treasures from the Lydian civilization, not Greek. The years passed and the issue faded, though it remained in the back of his mind. Then in the early 1980s, Acar moved to New York to work for a different Turkish newspaper, Milliyet, and subsequently struck out on his own as a freelancer. One day in 1984 he was visiting the Met and was surprised to see on display 50 pieces that closely matched the description he had of the Lydian hoard. They were labeled simply “East Greek treasure.” This was no chance sighting. Acar had been watching the Met’s public exhibitions and scouring its catalogs all along, looking for some sign that the museum indeed had the pieces. “I was shocked,” he recalled. “The villagers who had taken them knew what the items were. By this time, I knew them like the lines of my own palm.”

This was the proof Acar had been waiting for. He flew back to Turkey and got an interview with the minister of education, showing him what he’d managed to gather over the years. That local villagers had secretly excavated tumuli outside of town and sold the contents to smugglers, who had sold a hoard of golden Lydian treasures to a dealer and that it had been purchased by no less an institution than the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Photographs from the Turkish police comparing pieces seized from looters in the 1960s to the pieces at the Met all but proved that the Met’s pieces were Lydian and came from the same area as the others. “If that all turns out to be true,” the minister responded, “then we will sue the Met.” Acar broke the story in a series of seven articles in Milliyet in 1986, the first of which carried the eight-column headline “Turks Want the Lydian, Croesus Treasures Back.”

In Acar’s investigation, the path of the theft became clear. In 1965 four farmers from the towns of Gure and Usak dug into a tumulus called Ikiztepe and struck it big—these were tombs of the Lydian nobility and upper class and were laid out traditionally with a body on a bed, surrounded by precious objects. Police learned of the theft and were able to recover some of the objects in 1966, and these were handed over to Turkish museums. But most of the artifacts had already left the country. The looters sold their find to Ali Bayirlar, a Turkish antiquities smuggler, who sold the hoard to J. J. Klejman, the owner of a Madison Avenue art gallery, and George Zacos, a Swiss dealer. The Met bought successive groups of the Lydian treasures from 1966 to 1970. As often happened in such cases, when word spread in Usak that several local farmers had successfully sold their loot, others went frantically burrowing in other nearby tumuli, Aktepe and Toptepe, where they found still more Lydian pieces: gold, silver, pieces of exquisite artistry, and wall paintings from the tombs themselves. In a statement to the police, one looter described the efforts expended to burrow into the tombs:

We dug in turns for nine or 10 days....On the 10th day we reached the stones, each of which was almost 1.5 meters in height and 80 cms wide....It would be hard for five or six persons to lift one of them. ...We had tried to break the stones with sledgehammers and pokers, but were not successful. I exploded [the main entrance] using black powder.

The looters found a corpse that was, in the main, a pile of dust and a hunk of hair. But the gold and silver objects were undamaged. That one tomb held 125 pieces.

Meanwhile, the treasures purchased by the Met were presented to the museum’s acquisitions committee by Dietrich von Bothmer. It was the time of “don’t ask, don’t tell” when it came to buying unprovenanced treasures. The pieces were unique, and they were exquisite: acorn-shaped pendants along one heavy golden necklace; bracelets with intricately carved lion heads at each end; carefully ribbed and sculpted silver bowls; a silver ewer with the handle in the form of a graceful human figure arching backward. And of course the masterpiece, a tiny golden brooch in the shape of a hippocampus—a horse with wings and a fish’s tail, representing land, water, and air. The horse, barely an inch and a half in height, had three sets of tassels of three hanging, golden braids, each braid ending in an intricate golden ball in the shape of a pomegranate. There was not another like it in the world. The Met paid $1.5 million for the treasures over several years.

Under increasing pressure from the Turks, the Met dragged its feet, trying to head off a legal battle. The Turks tried asking politely, formally requesting the return of the Lydian hoard in July 1986 and sending their consul general to meet with museum officials. Meanwhile, inside the museum, documents later emerged that showed the Met knew full well that the “East Greek” pieces were what von Bothmer described as “the Lydian hoard,” the pieces Turkey had inquired about from the early 1970s forward. Hoving states bluntly in his memoir that everyone knew the stuff was contraband:

Dietrich von Bothmer asked what we should do if any damaging evidence were found that our East Greek treasure had been excavated illegally and smuggled out of Turkey....I was exasperated. “We all believe the stuff was illegally dug up,” I told him....“For Christ’s sake, if the Turks come up with the proof from their side, we’ll give the East Greek treasure back. And that’s policy. We took our chances when we bought the material.”

On May 29, 1987, the Republic of Turkey filed a lawsuit in Manhattan federal court against the Metropolitan Museum of Art, contending that several hundred artifacts had been illegally excavated and illegally exported from the country in the 1960s. This was a spectacularly bold move by a country with no track record in suing major institutions in foreign countries. Would it work? Turkey, represented by the American lawyers Harry Rand and Lawrence Kaye, was betting that the American justice system would judge the evidence fairly. Predictably, the Met filed a motion for dismissal, claiming it was far too late to sue for artifacts it had bought in good faith. But in 1990 Judge Vincent L. Broderick accepted the Turkish position. In pretrial discovery, the Met allowed a team of outside scholars to inspect the treasures for the first time. Among those who came was Kazim Akbiyikoglu of the Usak museum, who gave an affidavit providing the evidence that he had of the treasures’ origin. The Met’s defenses crumbled fairly quickly. Wall paintings were measured and found to fit the gaps in the walls of one tomb. Looters cooperating with the investigation described pieces they had stolen that matched the cache at the Met. The case was covered prominently in the press, and it was beginning to look like a black eye for the museum.

Seeking to salvage things, museum officials tried to negotiate a settlement. Under one plan, the Met would admit that the treasures were Turkish and would propose a kind of joint custody, in which the hoard—now known to be 363 pieces—would spend five years in New York and five years in Turkey. The Turks dispute this version, saying that the offer was to return merely a small portion of the hoard. Around Christmas 1992, the Met’s president, William Luers, and its director, Philippe de Montebello, traveled to Turkey to work out this deal with the minister of culture, Fikri Sa˘glar. But the minister refused to meet with them.

It was game over. Facing an imminent trial, the Met agreed in September 1993 to return the Lydian hoard, explaining in a press release: “Turkish authorities did provide evidence that most of the material in question may indeed have been removed clandestinely from the tombs in the Usak region, much of it only months before the museum acquired it. And second, we learned through the legal process of discovery that our own records suggested that some museum staff during the 1960s were likely aware, even as they acquired these objects, that their provenance was controversial.”

This was an astonishing admission by a major American museum. The Met had bought pieces that within a matter of weeks had gone directly from a group of looters, through middlemen, to the storerooms of the museum. Documents proved that the museum officials knew that these pieces were likely looted and essentially hid them for some 20 years. Nonetheless, the museum resisted Turkey’s demands for more than a decade and fought the lawsuit for six years, until finally acknowledging its actions.

Back in Turkey, the triumph was complete. Acar’s campaign had been taken up by the local Usak region, and the museum curator Kazim Akbiyikoglu—now his dear friend and ally—adopted the cause of stopping looting in his region. Acar’s slogan, “History is beautiful where it belongs,” became a poster that was found in libraries, classrooms, city buildings, and shops. The local Usak newspaper beat the drum for the return of the Lydian hoard. In October 1993, just a month after the Met’s concession, the artifacts arrived back in Turkey amid great celebration.

The lawsuit emboldened Turkey to chase other objects that had been taken improperly. The government pursued the auction house Sotheby’s for trafficking in looted artifacts and sued for objects being held in Germany and London. It also went after the Telli family, a ring of smugglers—through whom a billion dollars’ worth of stolen antiquities flowed—that Acar had written about in Connoisseur magazine. (The family sued Acar; he was acquitted. He then got death threats. He ignored them. He later learned that the plan was to kidnap him, tie him up, and ship him with an oxygen tank, to a Swiss museum.) The Getty Museum relinquished a sculpture from a Perge sarcophagus that had been sliced up and sold by looters. A German foundation gave up other portions of the same sculpture. Turkey became known as a leader in the battle against looting. By the latter half of the 1990s, the looters were on the defensive. Smugglers looked to work elsewhere. Turkey’s lawsuits made a clear statement of its intention to assert the country’s cultural rights.

For two years the treasures of the Lydian hoard were displayed in the Anatolian Civilizations Museum in Ankara, before being transferred in 1995 to Usak, to an aging one-room museum in the town, whose population had grown to one hundred thousand. Not only was the return of the Lydian hoard a source of undeniable pride in Usak but it also made restitution a popular cause in neighboring communities that once were centers of the ancient world. Even the looters came to regret their actions. On a visit to Usak in the late 1990s, Acar took three of the confessed grave robbers to the museum. “They were crying and said, ‘How stupid were we. We were idiots,’ ” he recalled with pride. “We created a consciousness.”

But that consciousness didn’t translate into broad viewership of the hoard. In 2006 the top culture official in Usak reported that in the previous five years, only 769 people had visited the museum. That may not be so terribly surprising, since only about 17,000 tourists had visited the region during that time, he said. Back in New York, the Met was unimpressed. “Those who’ve visited those treasures in Turkey is roughly equal to one hour’s worth of visitors at the Met,” Harold Holzer, the museum’s spokesman, remarked dryly.

That was bad enough, but the news soon turned dire. In April 2006 the newspaper Milliyet published another scoop on its front page: the masterpiece of the Lydian hoard, the golden hippocampus—the artifact that now stood as the symbol of Usak, its image published every day on the front page of the local newspaper—was a fake. The real hippocampus had been stolen from the Usak museum and replaced with a counterfeit.

How could such a thing happen? The police examined the hippocampus on display; it was indeed a fake. The original weighed 14.3 grams. The one in the museum was 23.5 grams.

But the bigger bombshell did not drop for several more weeks, when the Culture Ministry announced that the director of the museum, Kazim Akbiyikoglu—the man who had worked diligently for the return of the hoard to Usak, who had gathered evidence and gone to the United States and examined the hoard—was suspected in the theft.

Acar’s life work had been betrayed. And by a friend. “Of course I was disappointed,” said Acar. “I was shocked.”

It was not possible, he thought. Kazim Akbiyikoglu was one of the most honest people he knew. Akbiyikoglu’s father was a member of parliament, and he himself was one of the most respected archaeologists in Turkey. He had worked tirelessly to accomplish the return of the Lydian hoard. He believed, like Acar, that history was beautiful where it belonged, near its find site. He was held in the highest regard in Usak. If he knew three honest men in the world, Acar thought, Kazim Akbiyikoglu was one of them.

Acar spoke to Orhan Düzgün, the government representative for monuments and museums. “You can’t be right,” he told him. “Kazim is an honest man.” Düzgün demurred. The evidence pointed to Akbiyikoglu, he said. Acar refused to accept it. He went on television to defend his friend against the accusations.

For two weeks, Acar couldn’t sleep. It was embarrassing enough to Turkey that any of these treasures so hard won, so publicly demanded, would be lost through clumsiness or corruption. Indeed, when the hoard moved to Usak, Acar had begged the ministry to install a proper security system. There was none, or none that worked. But the news about Akbiyikoglu—this was beyond mortification. For 20 years, the curator had fought with local smugglers, trying to expose them, get the police to take notice. The local mafia had been trying to get rid of him. He had devoted night and day to archaeology and the museum. But over time, these efforts had taken a toll on his personal life. Akbiyikoglu was gone a lot from home; his wife, with whom he had two children, had an affair with the mayor of Usak and divorced him, marrying her lover. Akbiyikoglu found himself at loose ends. His ex-wife and her new husband were involved in a freak traffic accident in 2005, with Akbiyikoglu’s two children in the back seat. The wife and her new husband were killed. After that, Acar lost touch with his old friend until he read the news in the paper.

Today, the file of the Lydian treasures takes up four boxes in Acar’s office. His friend sits in jail while the trial over the theft stretches on, with no end in sight. The masterpiece of the Lydian hoard is gone. Acar thinks that perhaps the thieves have melted it down, to destroy the evidence.

History has disappeared, from where it once belonged.

“From the Book LOOT: The Battle Over the Stolen Treasures of the Ancient World by Sharon Waxman.

Copyright © 2008 by Sharon Waxman. Reprinted by arrangement with Times Books an Imprint of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.