Capturing Warsaw at the Dawn of World War II

As German bombs began falling on Poland in 1939, an American photographer made a fateful decision

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Indelible-Warsaw-631.jpg)

Like other members of his generation, Julien Bryan would never forget where he was or what he was doing when he learned that Germany had invaded Poland. But Bryan had a better reason to remember than most: on that September 3, 1939, he was stopped at what was then the Romanian-Polish border on a train bound for Warsaw.

“Why, at this moment, I did not turn around...I do not know,” Bryan would recall of learning of the invasion two days after the onslaught began. With bombs exploding nearby, the train resumed its cautious journey toward the capital—with Bryan on board for a front-row seat at the commencement of World War II.

Bryan, who came from Titusville, Pennsylvania, had seen combat as a 17-year-old ambulance driver in France during World War I. After graduating from Princeton, in 1921, he traveled widely, taking photographs and making travelogues or human-interest films along the way. That summer of 1939, he had been shooting peasant life in Holland. On September 7, he disembarked in predawn darkness in besieged Warsaw.

“I was in a city about to face perhaps the worst siege of all modern history,” Bryan would write. Other cities, of course, would suffer terrible assaults later in the war—London, Berlin, Hiroshima and many more—but early on, Warsaw was hit by wave after wave of modern bombers, to which the German Army added what Bryan called the “hot steel spray” of exploding artillery as it advanced.

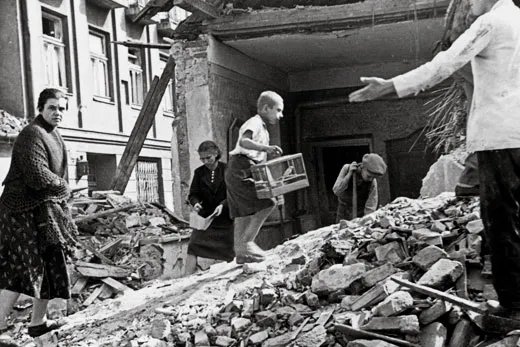

While the retreating Polish Army valiantly resisted the advancing German columns, Warsaw’s 1.3 million inhabitants were subjected to furious bombardment. Hospitals, churches and schools were hit. Bryan wrote that a 40-unit apartment building “looked as if a giant with an ice-cream scoop had taken out the entire central section.” Homeless families crowded the streets, pushing what remained of their belongings in wheelbarrows and baby carriages.

All this was happening, essentially, out of the world’s sight; Bryan was the sole foreign journalist left in the city. He acknowledged the journalistic tingle of getting “a grand scoop,” but he also recognized the historical imperative to capture the horror of modern warfare for the world to see. “I was not,” he realized, “making a travelogue.”

Bryan walked the streets with a Leica still camera and a Bell & Howell movie camera. Day by day the job grew riskier. He confessed that he and his Polish interpreter, Stephan Radlinski, often wanted to run when a bomb landed close by. “But neither of us ran, because each was afraid of what the other might think,” he wrote. On Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, incendiary bombs set 20 blocks of the Jewish quarter aflame.

Among shattered buildings near the Vistula River, Bryan took several frames of a boy clutching a bird cage.

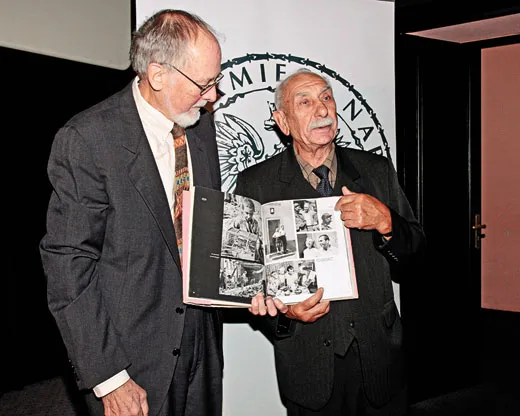

Twenty years later, after Bryan republished his photographs in a local newspaper, Zygmunt Aksienow identified himself as the boy in the photograph. Now 80, Aksienow recalls that two large bombs had fallen near his family’s apartment building and “the street was full of broken glass, furniture and parts of human bodies.” A bird cage “blew out of a house, along with a window” and landed in the rubble. Aksienow picked it up, thinking that the canary it held—very much alive—might belong to his cousin Zofia, a neighbor. “I was a scared 9-year-old, out looking for some sign of the normal life I was used to,” he says today.

Aksienow, who would grow up to be a coal miner, no longer recalls what happened to the canary, but he remembers clearly the cruel winter that followed the invasion. His family’s apartment had been heavily damaged and food was scarce, but just before the traditional Christmas Eve feast, young Zygmunt walked in with two buckets of fish, which he and a pal had stunned by tossing a hand grenade they’d found into the Vistula.

Bryan had no idea how he might get out of Warsaw. But on his 14th day there, the Germans declared a cease-fire to allow foreigners to depart by train through East Prussia. Certain that the Germans would confiscate any photographs of the destruction they had wrought, Bryan resolved to smuggle his film out. He gave some to departing companions to hide in their gear, and by one account wound yards of movie film he had the foresight to have processed in Warsaw around his torso. After reaching New York City, he reassembled an awesome trove: hundreds of still negatives and more than 5,000 feet of motion picture film.

That autumn, U.S. newspapers and magazines splashed Bryan’s photos across their pages. Life magazine printed 15 of his images, its weekly rival, Look, another 26—including the one of Aksienow with the caged canary. In 1940, Bryan put together a book about his experience, titled Siege; his documentary of the same name was nominated for an Academy Award.

Bryan died in 1974, just two months after receiving a medal from the Polish government for his still photography, which is preserved at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. His Warsaw film is listed on the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry as a “unique, horrifying record of the dreadful brutality of war.”

Mike Edwards was a writer and editor for National Geographic for 34 years.