Bodies of Evidence in Southeast Asia

Excavations at a cemetery in a Thai village reveal a 4,000-year-old indigenous culture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Charles-Higham-Ban-Non-Wat-631.jpg)

The lithe young woman rotates her wrists and hips, slowly and elegantly moving across the stage to the music of a traditional Cambodian orchestra. She seems the very embodiment of an apsara, the beautiful supernatural being that dances for the pleasure of Indian gods and heroes in their heavenly palaces. Reliefs of such creatures dot the nearby temples of Angkor Wat, where graceful poses have been frozen in stone for eight centuries by sculptors of the Khmer Empire.

This real-life apsara is dancing for tourists, but it is the plain white bangles on her wrists that catch my eye. I'd seen similar ones just a few days earlier, not far from this steamy Cambodian lowland, at an archaeological site in northeastern Thailand. They'd circled the arm bones of a woman who had died 2,000 years before the Khmer artisans first made stone sing at Angkor.

The bangles hint at something archaeologists have only lately grasped about Indochina, a region seen as an exotic but late-blooming hybrid of Indian and Chinese civilizations: long before these two neighboring behemoths cast their shadows in the first centuries A.D., Angkor's unnamed predecessors had forged their own sophisticated styles, along with complex irrigation systems, moated villages, long-distance trade and graves rich in beads and bronze artifacts. Indian and Chinese flavors only enriched this mix, producing the grandeur that today draws hundreds of thousands of visitors to central Cambodia each year.

More than 150 miles from Angkor Wat is a Thai village called Ban Non Wat. Standing on the edge of a vast 13- by 66-foot trench that he and local laborers have excavated, Charles Higham holds up a trowel for me to inspect; the steel tool is worn nearly to a nub. For the past 40 years, Higham, an archaeologist at the University of Otago in New Zealand, has labored in Thailand's dense jungles and rich rice fields to understand what took place here before the Khmer Empire rose to prominence, starting in the ninth century A.D. It's not easy. No written documents survive (only hints of an earlier culture in Chinese chronicles), and decades of war and genocide—not to mention leftover land mines—put much of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia off limits to researchers.

Although scholars had dismissed Angkor's ancestors as isolated tribes living in small settlements, peacefully growing rice as they awaited enlightenment from Indian Buddhist missionaries and Chinese traders, Higham and a few other archaeologists are describing a vigorous and innovative people who merely grafted outside influences onto an already vibrant way of life. Higham believes that about 4,000 years ago, rice farmers from southern China made their way down river valleys and joined sparse bands of hunter-gatherers who lived off the heavily forested land. Clearing the jungle for fields, the newcomers domesticated cattle, pigs and dogs and supplemented their diet with fish, shellfish and wild game.

Centuries later, these settlers had uncovered large deposits of tin and copper in the highlands of what is now Laos and Thailand. By 1000 B.C., they were extracting these metals, turning them into ingots and trading them to villages hundreds of miles away. Five centuries later, Southeast Asians were smelting iron—a technology they likely borrowed from India or China—and building substantial towns. Non Muang Kao, now an archaeological site in eastern Thailand, encompassed more than 120 acres and housed as many as 2,500 people.

Higham says the ancient 30-acre settlement at Ban Non Wat is an "extraordinary find." Thanks to the highly alkaline soil in this area, which leaves bone intact, he has uncovered a well-preserved cemetery that spans a thousand years—from Neolithic times (1750 to 1100 B.C.) through the Bronze Age (1000 to 420 B.C.) and Iron Age (420 B.C. to A.D. 500). The graves are yielding rare insights into the pre-Angkor life of mainland Southeast Asia.

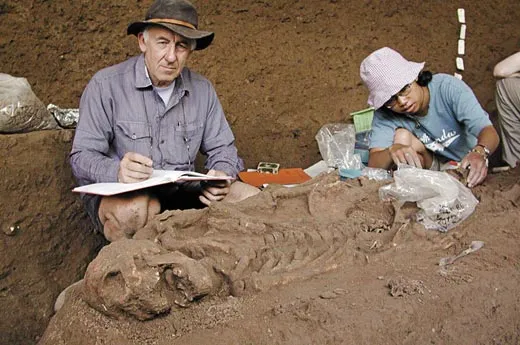

Higham's trench has several levels, each containing burials from a particular era. We climb down a ladder to the bottom of a rectangular pit, where two women using trowels and brushes painstakingly expose a skeleton; a long-haired young man sketches another in his notebook. On the opposite side of the trench, other women are digging pits looking for additional graves, and men use pulleys to bring baskets of earth up to be dumped and then sieved for missed artifacts.

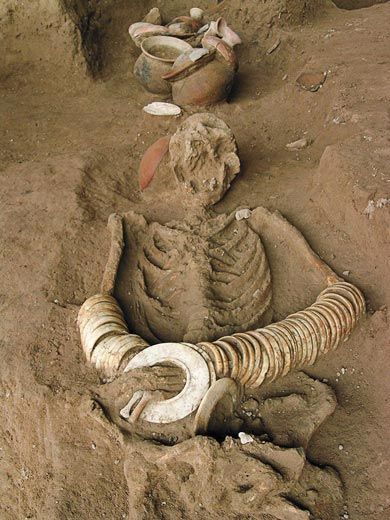

Higham moves among the workers, joking with them in the local dialect and checking on their progress. A white canopy flaps over us in the breeze, blocking the intense subtropical sun. Higham points out a Bronze Age skeleton with 60 shell bangles and an infant surrounded by a wealth of pots and beads. Other graves clearly held high-status individuals, as shown by the tremendous effort that went into the burials; they were deep, with wooden coffins and elaborate offerings such as rare bronzes. The findings, Higham says, indicate that a social hierarchy was in place by the Bronze Age. Moreover, the remains of rice and pig bones, Higham says, "are evidence of ritual feasting, and an elaborate and highly formalized burial tradition."

This sort of archaeological research is increasingly rare. In many parts of the world, including North America, cultural mores prevent or curtail detailed examination of human remains, for reasons that Higham finds reasonable. "I have a cottage in England next to the village church and cemetery," he says, "and I wouldn't want a Thai archaeologist mucking around there." But Ban Non Wat's villagers express no such concerns, even those working at the site, brushing away dirt from bones that may belong to ancestors. Higham says that cremation came to the area in the first centuries A.D. (the result of Indian influence), and today's villagers "don't relate to the bones they find."

At another nearby site, called Noen U-Loke, detailed analysis of bones found among 127 graves suggests high rates of infant mortality. One of the more poignant finds was the remains of a child who likely suffered from cerebral palsy and was adorned with ivory bangles—a sign the child was loved and valued by the community. Individuals who survived infancy appear to have lived relatively healthy lives, despite evidence of leprosy and tuberculosis. Wild pigs, deer, turtles, along with domesticated plants and animals, provided a diverse diet, and dental health was surprisingly good.

But there was violence, too. The skull of one woman was cleaved nearly in half by two blows with a sharp instrument. Forensic evidence suggests she was standing—and therefore alive—when attacked. She had not been an outcast; her skeleton was buried with jewelry. Another man died after an iron projectile pierced his spine.

Motioning me to follow him, Higham climbs back up the ladder and trudges across a muddy track past clucking chickens and mangy dogs. Soon we come to a slight rise. Beyond are several more small rises, separated by shallow water. These formations puzzled the archaeologists who first encountered them several decades ago. But we now know that villages ringed by moats a mile or more in circumference were a common feature once iron spades and shovels made construction of them possible in the Iron Age. In fact, aerial and satellite photographs reveal the ghostly rings of long-lost villages across huge swaths of Thailand and Cambodia.

The moats may have served several purposes beyond protecting settlements from invaders: they collected water during the dry season and channeled it during the rainy season. And the earthen berms ringing the moats provided foundations for palisades. Higham sees the moats and other defensive structures as further evidence that Khmer civilization did not originate abroad. "You already have social complexity here at 400 B.C.," he says, gesturing around. "This was not brought from India—it was indigenous."

Two-and-a-half millennia later, most of the wildlife is gone, burial practices are different and knowledge about the ancient beliefs of Southeast Asians is scarce. Higham nevertheless sees a thread stretching from the Bronze Age settlements to the present day. At least one connection is easy to spot. On a journey to Phimai, Thailand, I stop in a pleasant village, Ban Prasat, lazing in the afternoon heat. The village is dotted with excavated graves similar to those at Ban Non Wat, proof of its ancient heritage. In the yard of each dwelling is a small "spirit house," a shelter for local spirits that could otherwise cause mischief. Such spirit houses—reflecting an animistic tradition that predates the arrival of Hinduism or Buddhism—are found throughout Cambodia, Laos and Thailand, even in front of modern office buildings in trendy Bangkok. While archaeologists like Higham methodically excavate ancient settlements, tantalizing evidence of Southeast Asia's thriving indigenous culture remains hidden in plain sight.

Andrew Lawler wrote about Egypt's greatest temple in the November 2007 issue.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/andrew2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/andrew2.png)