Why Benedict Arnold Turned Traitor Against the American Revolution

The story behind the most famous betrayal in U.S. history shows the complicated politics of the nation’s earliest days

:focal(326x280:327x281)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/64/52646131-a83b-492c-83a7-e98d20e2f28e/may2016_c01_colbenedictphilbrick-wr-v4.jpg)

He was short, solidly built (one acquaintance remembered that “there wasn’t any wasted timber in him”) and blessed with almost superhuman energy and endurance. He was handsome and charismatic, with black hair, gray eyes and an aquiline nose, and he carried himself with the lissome elegance of a natural athlete. A neighbor from Connecticut remembered that Benedict Arnold was “the most accomplished and graceful skater” he had ever seen.

He was born in 1741, a descendant of the Rhode Island equivalent of royalty. The first Benedict Arnold had been one of the colony’s founders, and subsequent generations had helped to establish the Arnolds as solid and respected citizens. But Arnold’s father, who had settled in Norwich, Connecticut, proved to be a drunkard; only after his son moved to New Haven could he begin to free himself from the ignominy of his childhood. By his mid-30s he had had enough success as an apothecary and a seagoing merchant to begin building one of the finest homes in town. But he remained hypersensitive to any slight, and like many gentlemen of his time he had challenged more than one man to a duel.

From the first, he distinguished himself as one of New Haven’s more vocal and combative patriots. On hearing of the Boston Massacre, he thundered, “Good God, are the Americans all asleep and tamely giving up their glorious liberties?” When in April 1775 he learned of the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord, he seized a portion of New Haven’s gunpowder supply and marched north with a company of volunteers. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, he convinced Dr. Joseph Warren and the Massachusetts Committee of Safety to authorize an expedition to capture Fort Ticonderoga in New York State and its 80 or more cannons.

As it turned out, others had the same idea, and Arnold was forced to form an uneasy alliance with Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys before the two leaders strode side by side into Ticonderoga. While Allen and his men turned their attention to consuming the British liquor supply, Arnold sailed and rowed to St. John, at the opposite end of Lake Champlain, where he and a small group of men captured several British military vessels and instantly gave America command of the lake.

Abrupt and impatient with anything he deemed superfluous to the matter at hand, Arnold had a fatal tendency to criticize and even ridicule those with whom he disagreed. When a few weeks later a Continental Army officer named James Easton dared to question the legitimacy of his authority as the self-proclaimed commodore of the American Navy on Lake Champlain, Arnold proceeded to “kick him very heartily.” It was an insult Easton never forgot, and in the years ahead, he became one of a virtual Greek chorus of Arnold detractors who would plague him for the rest of his military career. And yet, if a soldier served with him during one of his more heroic adventures, that soldier was likely to regard him as the most inspiring officer he had ever known.

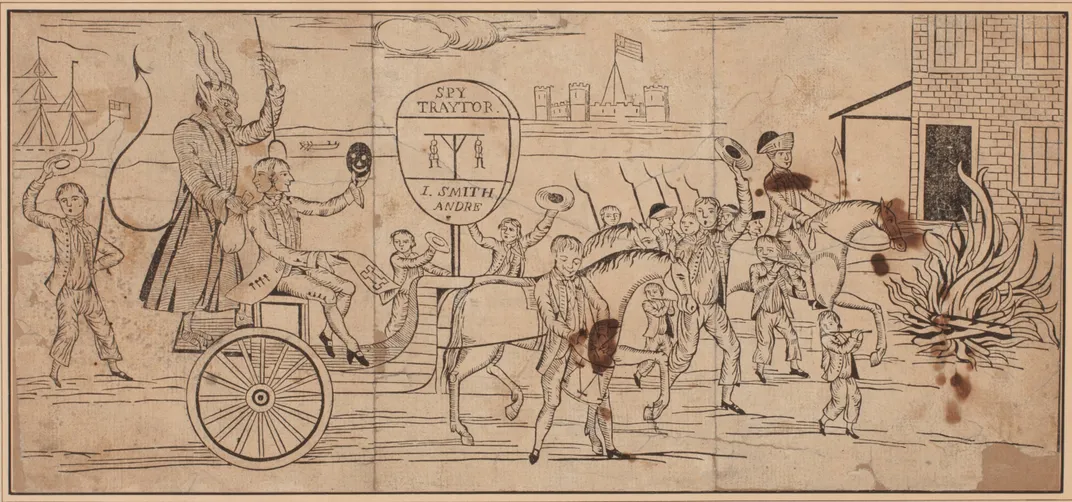

The American Revolution as it actually unfolded was so troubling and strange that once the struggle was over, a generation did its best to remove all traces of the truth. Although it later became convenient to portray Arnold as a conniving Satan from the start, the truth is more complex and, ultimately, more disturbing. Without the discovery of his treason in the fall of 1780, the American people might never have been forced to realize that the real threat to their liberties came not from without, but from within.

**********

In that first Revolutionary spring of 1775, Arnold learned of the death of his wife, Margaret. Upon returning from Lake Champlain to New Haven, he visited her grave with his three young sons at his side. Arnold’s letters to her prior to the Revolution had been filled with pleas for her to write more often, and his grief upon her death seems to have been almost overpowering. And yet, for someone of Arnold’s restless temperament, it was inconceivable to remain in New Haven with his sorrow. “An idle life under my present circumstances,” he explained, “would be but a lingering death.” After just three weeks, Arnold left his children under the care of his sister Hannah and was on his way back to Cambridge, where he hoped to bury his anguish in what he called “the public calamity.” Over the next three years—in Canada, on Lake Champlain, in Rhode Island and Connecticut and again in New York—he made himself indispensable to his commander in chief, George Washington, and the Revolutionary cause.

It is impossible to say when 37-year-old Benedict Arnold first met 18-year-old Peggy Shippen, but we do know that on September 25, 1778, he wrote her a love letter—much of it an exact copy of one he’d sent to another woman six months before. But if the overheated rhetoric was recycled, Arnold’s passion was genuine. Knowing of “the affection you bear your amiable and tender parents,” he had also written to Peggy’s loyalist-leaning father. “Our difference in political sentiments will, I hope, be no bar to my happiness,” he wrote. “I flatter myself the time is at hand when our unhappy contest will be at an end.” He also assured Peggy’s father that he was wealthy enough “to make us both happy” and that he had no expectations of any kind of dowry.

Here in this letter are hints as to the motives behind Arnold’s subsequent behavior. While lacking the social connections of the Shippens, who were the equivalent of Philadelphia aristocracy, Arnold had had prospects of accumulating a sizable personal fortune. Now the British had abandoned their occupation of the revolutionaries’ capital, and Washington, needing something for Arnold to do while he recuperated from a battle-shattered left thigh, had named him the city’s military governor. Having lost once-significant wealth, Arnold embarked on a campaign of secret, and underhanded, schemes to re-establish himself as a prosperous merchant. That end—and those means—were not uncommon among officers of the Continental Army.

But in September 1778 he did not yet have the money he needed to maintain Peggy in the style to which she was accustomed. There was also the matter of the Shippens’ politics. They might not be outright loyalists, but they had a decided distaste for the radical patriots who were waging an undeclared war on Philadelphia’s upper classes now that the British had gone. Given Arnold’s interest in Edward Shippen’s daughter and his lifelong desire to acquire the wealth his bankrupt father had denied him, it is not surprising that he embraced the city’s marginalized nobility with a vengeance.

Thumbing his nose at the pious patriots who ruled the city, he purchased an ornate carriage and entertained extravagantly at his new residence, the same grand house the British general William Howe had occupied. He attended the theater, even though the Continental Congress had advised the states to ban such entertainments as “productive of idleness, dissipation and general depravity.” He issued passes to suspected loyalists wanting to visit friends and relatives in New York City, which was held by the British. He even appeared at a ball in a scarlet uniform, which led a young lady whose father had been arrested for corresponding with the British to joyfully exclaim, “Heyday, I see certain animals will put on the lion’s skin.”

**********

One of Arnold’s misfortunes was that Joseph Reed had become a champion, however unlikely, of Pennsylvania’s radical patriots. A London-educated lawyer with an English wife, Reed had a reputation as one of Philadelphia’s finest and most ambitious attorneys before the Revolution. But the Reeds had not fit well into the upper echelons of Philadelphia society. Reed’s pious wife complained that one of Peggy Shippen’s relatives had accused her of being “sly,” claiming that “religion is often a cloak to hide bad actions.”

Reed had served on Washington’s staff as adjutant general at the beginning, when Washington faced the daunting task of dislodging the British from Boston in 1775. But by the end of the year, with the Continental Army run out of New York City and retreating across New Jersey, he had lost faith in his commander. Reed was away from headquarters when a letter arrived from the army’s second-ranking officer, Maj. Gen. Charles Lee. Assuming the letter related to official business, Washington promptly broke the seal. He soon discovered that Reed had established his own line of communication with Lee and that the primary topic of their correspondence was the failings of their commander in chief.

Washington forwarded the letter to Reed with a note explaining why he had opened it, but otherwise let him twist in the icy emptiness of his withheld wrath. He kept Reed on, but their intimacy had ended.

Brilliant, mercurial and outspoken, Reed had a habit of antagonizing even his closest friends and associates, and he eventually left Washington’s staff to serve in a variety of official capacities, always restless, always the smartest, most judgmental person in the room. As a New England minister wrote to Washington, the man was “more formed for dividing than uniting.”

In the fall of 1778, Reed stepped down as a Pennsylvania delegate to Congress to help the state’s attorney general prosecute 23 suspected loyalists for treason. He lost 21 of those cases—there wasn’t much evidence to work with—but the position established him as one of the city’s most zealous patriots. That November, the two wealthy Quakers who had been convicted were hanged.

In an apparent act of protest, Arnold hosted “a public entertainment” at which he received “not only Tory [or loyalist] ladies but the wives and daughters of persons proscribed by the state” in “a very considerable number,” Reed sputtered in a letter to a friend. Perhaps contributing to his ire was the fact that he and his wife had recently moved into the house next to Arnold’s and hadn’t been invited to the party.

By December Reed was president of the state’s Supreme Executive Council, making him the most powerful man in one of the most powerful states in the country. He quickly made it clear that conservative patriots were the enemy, as were the Continental Congress and the Continental Army. As council president, he insisted that Pennsylvania prevail in any and all disputes with the national government, regardless of what was best for the United States as a whole. Philadelphia was at the vortex of an increasingly rancorous struggle involving almost all the seminal issues related to creating a functioning democratic republic, issues that would not begin to be resolved until the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

Amid all this upheaval, Reed launched an investigation into the military governor’s conduct. The prosecution of Benedict Arnold—a Washington favorite, an emblem of national authority and a friend to Philadelphia’s wealthy—would be the pretext to flex his state’s political muscle. And it would lead Arnold to doubt the cause to which he had given so much.

**********

By late January 1779, Arnold was preparing to leave the military. Officials in New York State, where he was held in high regard, had encouraged him to consider becoming a landowner on the scale of the loyalist Philip Skene, whose vast estate at the southern tip of Lake Champlain had been confiscated by the state. Arnold’s financial dealings in Philadelphia had failed to yield the anticipated returns. Becoming a land baron in New York might be the way to acquire the wealth and prestige that he had always craved and that Peggy and her family expected.

By early February he had decided to journey to New York, stopping to visit Washington at his headquarters in New Jersey. Reed, fearing that Arnold might escape to New York before he could be brought to justice for his sins in Philadelphia, hurriedly put together a list of eight charges, most of them based on rumor. Given the pettiness of many of the charges (which included being ungracious to a militiaman and preferring loyalists to patriots), Reed appeared to be embarked on more of a smear campaign than a trial. That Arnold was guilty of some of the more substantive charges (such as illegally purchasing goods upon his arrival in Philadelphia) did not change the fact that Reed lacked the evidence to make a creditable case against him. Arnold knew as much, and he complained of his treatment to Washington and the commander’s family of officers.

Washington had refused to take sides in the dispute between Philadelphia’s radicals and conservatives. But he knew that Reed was hardly the steadfast patriot he claimed to be. For the last year, a rumor had been circulating among the officers of the Continental Army: Reed had been in such despair over the state of the war in late December 1776 that he’d spent the night of Washington’s assault on Trenton at a home in Hessian-occupied New Jersey, poised to defect to the British in the event of an American defeat. In that light, his self-righteous prosecution of Quakers and other loyalists seemed hypocritical in the extreme. It’s likely that Washington had heard at least some version of the claim, and just as likely that he took the charges against Arnold with a grain of salt. Still, Reed’s position on the Supreme Executive Council required that Washington accord him more civility than he probably deserved.

On February 8, 1779, Arnold wrote to Peggy from the army’s headquarters in Middlebrook, New Jersey. “I am treated with the greatest politeness by General Washington and the officers of the army,” he assured her. He claimed that the consensus at headquarters was that he should ignore the charges and continue on to New York.

Despite this advice, he had resolved to return to Philadelphia, not only to clear his name but because he was so desperately missing Peggy. “Six days’ absence without hearing from my Dear Peggy is intolerable,” he wrote. “Heavens! What must I have suffered had I continued my journey—the loss of happiness for a few dirty acres. I can almost bless the villainous...men who oblige me to return.” In utter denial regarding his complicity in the trouble he was now in, he was also deeply in love.

**********

Back in Philadelphia, Arnold came under near-ceaseless attack from the Supreme Executive Council. But since the council was unwilling to provide the required evidence—primarily because it did not have any—the Congressional committee appointed to examine the charges had no choice but to find in Arnold’s favor. When the council threatened to withhold the state militia and the large number of state-owned wagons upon which Washington’s army depended, Congress tabled its committee’s report and turned the case over to Washington for a court-martial.

More than a few Congressional delegates began to wonder what Reed was trying to accomplish. As a patriot and a Philadelphian, Congress’s secretary Charles Thomson had once considered Reed a friend. No more. Reed’s refusal to bring forward any legitimate evidence, combined with his continual assaults on the authority and integrity of Congress, made Thomson wonder whether his former friend was trying to destroy the political body upon which the country’s very existence depended. Was Reed, in fact, the traitor?

The previous summer Reed had received an offer of £10,000 if he would assist a British peace commission’s efforts with Congress. In a letter published in a Philadelphia newspaper, Reed claimed to have indignantly refused the overture. But had he really? One of the commissioners had recently assured Parliament that secret efforts were under way to destabilize the government of the United States and that these “other means” might prove more effective in ending the war than military attempts to defeat Washington’s army. There is no evidence that Reed was indeed bent on a treasonous effort to bring down Congress, but as Thomson made clear in a letter to him, his monomaniacal pursuit of Arnold was threatening to accomplish exactly that.

**********

In the meantime, Arnold needed money, and fast. He had promised Edward Shippen that he would bestow “a settlement” on his daughter prior to their marriage as proof that he had the financial resources Peggy’s father required. So in March of 1779, Arnold took out a loan for £12,000 and, with the help of a sizable mortgage, bought Mount Pleasant, a mansion on 96 acres beside the Schuylkill that John Adams had once claimed was “the most elegant seat in Pennsylvania.”

There was one hitch, however. Although he had technically purchased Peggy a mansion, they were not going to be able to live in it, since Arnold needed the rental payments from the house’s current occupant to help pay the mortgage.

Harassed by Reed, carrying a frightening burden of debt, Arnold nonetheless had the satisfaction of finally winning Edward Shippen’s consent, and on April 8, he and Peggy were married at the Shippens’ house. Now Arnold had a young, beautiful and adoring wife who was, he proudly reported the next morning to several of his friends, good in bed—at least that was the rumor the Marquis de Chastellux, a major general in the French Army who was fluent in English, heard later when visiting Philadelphia.

However, within just a few weeks, Arnold was finding it difficult to lose himself in the delights of the connubial bed. Reed had not only forced a court-martial upon Arnold; he was now attempting to delay the proceedings so that he could gather more evidence. What’s more, he had called one of Washington’s former aides as a witness, an even more disturbing development since Arnold had no idea what the aide knew. Arnold began to realize that he was, in fact, in serious trouble.

Aggravating the situation, his left leg was not healing as quickly as he had hoped, and his right leg became wracked by gout, making it impossible for him to walk. Arnold had been in tight spots before, but always had been able to do something to bring about a miraculous recovery. But now, what was there to do?

If the last nine months had taught him anything, it was that the country to which he had given everything but his life could easily fall apart. Instead of a national government, Congress had become a facade behind which 13 states did whatever was best for each of them. Indeed, it might be argued that Joseph Reed was now more influential than all of Congress combined.

What made all of this particularly galling was the hostility that Reed— and apparently most of the American people—held toward the Continental Army. More and more Americans regarded officers like Arnold as dangerous hirelings on the order of the Hessian mercenaries and British regulars, while local militiamen were looked to as the patriotic ideal. In reality, many of these militiamen were employed by community officials as thuggish enforcers to terrorize local citizens whose loyalties were suspect. In this increasingly toxic and volatile environment, issues of class threatened to transform a collective quest for national independence into a sordid and self-defeating civil war.

By the spring of 1779, Arnold had begun to believe that the experiment in independence had failed. And as far as he could tell, the British had a higher regard for his abilities than his own country did. Gen. John Burgoyne was in London defending himself before Parliament with the claim that if not for Arnold, his army would have won the Battle of Saratoga. That February, the Royal Gazette had referred sympathetically to his plight in Philadelphia: “General Arnold heretofore had been styled another Hannibal, but losing a leg in the service of the Congress, the latter considering him unfit for any further exercise of his military talents, permit him thus to fall into the unmerciful fangs of the executive council of Pennsylvania.” Perhaps the time was right for him to offer his services to the British.

**********

Arnold is usually credited with coming up with the idea himself, but there are reasons to think the decision to turn traitor originated with Peggy. Certainly the timing is suspect, following so soon after their marriage. Arnold was bitter, but even he had to admit that the Revolution had catapulted him from the fringes of respectability in New Haven to the national stage. Peggy, on the other hand, regarded the Revolution as a disaster from the start. Not only had it initially forced her family to flee from Philadelphia; it had reduced her beloved father to a cringing parody of his former self. How different life had been during those blessed months of the British occupation, when noble gentleman-officers had danced with the belles of the city. With her ever-growing attachment to Arnold fueling her outrage, she had come to despise the revolutionary government that was now trying to destroy her husband.

By marrying Peggy, Arnold had attached himself to a woman who knew how to get what she wanted. When her father had initially refused to allow her to marry Arnold, she had used her seeming frailty—her fits, her hysteria, whatever you wanted to call it—to manipulate him into agreeing to the engagement for fear that she might otherwise suffer irreparable harm. Now she would get her way with her equally indulgent husband.

Given the ultimate course of Arnold’s life, it is easy to assume that he had fully committed himself to treason by the time he sent out his first feelers to the British in early May 1779. But that was not the case. He still felt a genuine loyalty to Washington. On May 5, Arnold wrote his commander what can only be described as a hysterical letter. The apparent reason for it was the delay of his court-martial to June 1. But the letter was really about Arnold’s fear that he might actually do as his wife suggested. “If your Excellency thinks me criminal,” he wrote, “for heaven’s sake, let me be immediately tried and if found guilty executed.”

What Arnold wanted more than anything now was clarity. With the court-martial and exoneration behind him, he might fend off Peggy’s appeals. Joseph Reed, however, was bent on delaying the court-martial for as long as possible. In limbo like this, Arnold was dangerously susceptible to seeing treason not as a betrayal of all he had held sacred but as a way to save his country from the revolutionary government that was threatening to destroy it.

In his anguish on May 5, he offered Washington a warning: “Having made every sacrifice of fortune and blood, and become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet the ungrateful returns I have received of my countrymen, but as Congress have stamped ingratitude as a current coin I must take it. I wish your Excellency for your long and eminent services may not be paid of in the same coin.”

In the reference to money, Arnold unintentionally betrayed the real reason he had been moved to consider this course. If he handled the negotiations correctly, turning traitor could be extremely lucrative. Not only would he be able to walk away from his current financial obligations, he might command a figure from the British that would make him independently wealthy for life.

On May 10, an emissary from Arnold reached John André, a British captain whom Peggy had come to know well in Philadelphia. But now André was living in New York City, which would become crucial to the Revolution’s prospects in the months ahead. Arnold wanted to explore the possibility of defecting, but first he needed to be assured of two things: Were the British in this war to stay? And how much were his services worth?

In the tortuous months ahead, Arnold would survive his oft-delayed court-martial with a reprimand, and Washington would restore him to command. But the emissary’s visit was the first tentative step that led, in late summer-fall of 1780, to Arnold’s doomed effort to hand over the fortifications at West Point to the enemy.

By reaching out to the British, Arnold gave his enemies the exquisite satisfaction of having been right all along. Like Robert E. Lee at the beginning of the American Civil War, Arnold could have declared his change of heart and simply shifted sides. But as he was about to make clear, he was doing this first and foremost for the money.

Editor-in-chief Michael Caruso interviewed author Nathaniel Philbrick on our Facebook page about Benedict Arnold. Watch the video and follow us for more great history stories from Smithsonian magazine and Smithsonian.com.

Valiant Ambition