Below the Rim

Humans have roamed the Grand Canyon for more than 8,000 years. But the chasm is only slowly yielding clues to the ancient peoples who lived below the rim

It was early May, but a raw breeze was blowing as we tracked bootprints through an inch of new-fallen snow. Shortly after dawn, we had parked on the Desert View Drive and set off through the ponderosa forest toward the Grand Canyon, leaving behind the tourist traffic hurtling along the canyon’s South Rim.

After hiking a mile, the three of us—mountaineer Greg Child, photographer Bill Hatcher and I—emerged abruptly from the trees to stand on a limestone promontory overlooking the colossal chasm. The view was predictably sublime—distant ridges and towers blurred to pastel silhouettes by the morning haze; the North Rim, 20 miles distant, smothered in storm; the turgid flood of the Colorado River silenced by the 4,800-foot void beneath our feet.

But we hadn’t come for the scenery.

We scrambled off the point, slithering among boulders as we lost altitude. A few hundred feet below the rim we were stopped by a band of rock that dropped nearly ten feet. We tied a rope to a clump of serviceberry bushes and slid down it, leaving the rope in place for our return.

We had found our way through the canyon’s Kaibab Limestone cap rock and alighted atop a 400-foot precipice of Coconino Sandstone. For miles on either side, this band of grayish orange rock was too sheer to descend, but the prow itself was broken into sharp-angled steps. We took the line of least resistance, sidling around towers and straddling grooves, with the emptiness below our soles reminding us of the consequences of a misstep.

Then the going got really tricky. We faced inward, moving slowly from one handhold and foothold to the next. All three of us are experienced climbers, but the terrain was as difficult as any of us dared tackle without ropes and hardware. Just as the “route” threatened to blank out, Greg, in the lead, placed his foot in a rounded hollow that gave him just enough purchase to keep his balance. Another hollow for his other foot—six in a row, all told. From years of prowling through the Southwest, we knew that these subtle depressions were man-made. More than seven centuries ago, some daring acrobat had pounded them with a rock harder than sandstone.

So it went for the next 90 minutes: wherever the path seemed to vanish, early pioneers had stacked a platform of flat rocks here or carved a few footholds there. At last we came out onto a broad saddle between the plunging prow and an isolated butte to the north. As we sat eating lunch, we found red and gray and white flakes of chert scattered in the dirt—the debris of an arrowhead-making workshop.

Bill looked up at the route we had just descended. Had we stumbled upon it from below, we might well have judged it unclimbable. “Pretty amazing, huh?” was all he could say. But what was the trail for, and what long-vanished culture had created it?

The Grand Canyon occupies such an outsize place in the public imagination, we can be forgiven for thinking we “know” it. More than four million tourists visit the canyon each year, and the National Park Service funnels the vast majority of them through a tidy gantlet of attractions confined to a relatively short stretch of the South Rim. Even people who have never visited America’s greatest natural wonder have seen so many photographs of the panorama from Grandview Point or Mather Point that the place seems familiar to them.

But the canyon is a wild and unknowable place—both vast (the national park alone covers about 1,902 square miles, about the size of Delaware) and inaccessible (the vertical drops vary from 3,000 feet to more than 6,000). The chasm lays bare no fewer than 15 geological layers, ranging from the rim-top Kaibab Limestone (250 million years old) to the river-bottom Vishnu Schist (as old as two billion years). The most ecologically diverse national park in the United States, the Grand Canyon embraces so many microclimates that hikers can posthole through snowdrifts on the North Rim while river runners on the Colorado below are sunbathing in their shorts.

Among the canyon’s many enigmas, one of the most profound is its prehistory—who lived here, and when, and how, and why. At first blush, the Grand Canyon looks like a perfect place for ancient peoples to have occupied, for the Colorado River is the most abundant and reliable source of water in the Southwest. Yet before the river was dammed, it unleashed recurring catastrophes as it flooded its banks and scoured out the alluvial benches where ancients might have been tempted to dwell and farm. For all its size and geological variety, the canyon is deficient in the kinds of natural alcoves in which prehistoric settlers were inclined to build their villages. And—as Bill, Greg and I discovered that May morning—it can be fiendishly difficult to navigate. “The canyon’s got a lot to offer, but you have to work hard for it,” says National Park Service archaeologist Janet Balsom. “It’s really a marginal environment.”

And yet the Grand Canyon is riddled with prehistoric trails, most of which lead from the rim down to the riverbed. Some of them are obvious, such as the routes improved by the park service into such hikers’ boulevards as the Bright Angel and South Kaibab trails. Most of the others are obscure. Archaeologists have largely left them to be explored by a few fanatically devoted climbers.

The archaeology of other Southwestern regions—New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon, for instance, or Colorado’s Mesa Verde—has yielded a far more comprehensive picture of what it was like a millennium or so ago. Says Balsom: “You have to remember, only 3.3 percent of the Grand Canyon has been surveyed, let alone excavated.” Only in the past 50 years have archaeologists

focused significant attention on the Grand Canyon—sometimes digging in places so remote they had to have helicopter support—and only recently have their efforts borne much fruit.

Broadly speaking, archaeological evidence shows that humans have roamed the canyon for more than 8,000 years. The dimmest hint of a Paleo-Indian presence, before 6500 b.c., is succeeded by rock art and artifacts from a vivid but mysterious florescence of Archaic hunter-gatherers (6500 to 1250 b.c.). With the discovery of how to cultivate corn, bands of former nomads started building semipermanent villages on canyon terraces sometime before 1000 b.c. Two millennia later, by a.d. 1000, at least three distinct peoples flourished within the canyon, but their identities and ways of living remain poorly understood. From a.d. 1150 to 1400, there may have been a hiatus during which the entire canyon was abandoned—why, we can only guess.

Today, just one group of Native Americans—the Havasupai—lives within the canyon. And even though their elders can recite origin stories with unblinking self-assurance, the tribe presents anthropologists with puzzles every bit as vexing as the ones that cling to the vanished ancients.

The blank spaces in the timeline, the lost connections between one people and another, confound experts who only slowly are illuminating the lives that were lived so long ago below the rim.

The Grand Canyon has frustrated Western explorers from the beginning. The first Europeans to behold it were a splinter party from Francisco Vásquez de Coronado’s monumental Southwest entrada of 1540-42. Their commander dispatched them to chase down a rumor about “a large river” to the west. “Several days down the river,” some Hopi informants had told them, “there were people with very large bodies.”

Guided by four Hopi men, this party, headed by one García López de Cárdenas, took 20 days to reach the Grand Canyon—at least twice as long as it should have. Apparently, the Hopi were leading Cárdenas’ men the long way around to divert them from their own vulnerable villages.

Cárdenas’ guides took the soldiers to a point on the South Rim not far from where the three of us slid off the precipice that morning in May 2005, choosing one of the few stretches where no trail led into the canyon. Misjudging the scale of the gorge, the Spaniards thought the river below a mere six feet wide, instead of more than a hundred yards. Cárdenas sent his three nimblest scramblers over the edge to find a way down, but after three days—during which they got only a third of the way—they returned to report that the descent was impossible. Cárdenas, who was hoping to find an easy route to the Pacific, turned back in exasperation.

The first U.S. explorer to reach the Colorado River within the Grand Canyon was a government surveyor, Lt. Joseph C. Ives, who did it with guidance from Hualapai Indians in 1858. He was no more pleased than Cárdenas. The entire region, he swore in his official report, was “altogether valueless.” That judgment did not prevent John Wesley Powell from boating down the Colorado River in 1869, nor a wave of miners from invading the canyon in the 1880s, nor the establishment of the Grand Canyon National Monument in 1908 and National Park in 1919.

In 1933, three Civilian Conservation Corps workers building a trail in the canyon took an off day to explore a remote cave. As they were hunting for Indian objects inside it, they later told their boss, they discovered three figurines, each made from a single willow twig. It seemed that the objects, each less than a foot in height, had been secreted away in one of the most inaccessible niches.

Since then, more than 500 such figurines have been discovered. On a windy, rainy day, Bill, Greg and I stopped by the Grand Canyon National Park Museum Collection, where curator Colleen Hyde pulled about a dozen of these split-twig figurines out of their storage drawers.

They ranged in length from an inch to 11 inches, but all had been made by the same method. Each artist had taken a stick of willow or skunkbush and split it lengthwise until it was held together only at one end, then folded the two ends around each other until the second could be tucked inside a wrapping formed by the first. The result appears to be an effigy of either a deer or a bighorn sheep, both of which would have been an important source of food.

In recent years, many of the figurines have been carbon-dated, yielding dates ranging from 2900 to 1250 b.c.—squarely in the late Archaic period of this region. Except for a pair of broken projectile points, they are the oldest artifacts ever found in the Grand Canyon. The Archaic hunter-gatherers—people who had yet to discover corn or pottery or the bow and arrow—held to this rigorous artistic tradition for nearly 17 centuries, or about as long as the span from late Roman statuary to Jackson Pollock.

Across the Southwest, only two areas are known to have produced split-twig figurines. A cluster centered in canyons in southeastern Utah consists of effigies wrapped according to a different method, producing a different-looking animal, and they are found only in domestic contexts, including trash dumps. But all of the Grand Canyon figurines have been discovered in deep caves in the Redwall Limestone stratum—by far the most difficult geologic layer in the canyon to climb through, because its sheer precipices lack handholds and footholds. In these caves, the objects were placed under flat rocks or small cairns, and no accompanying relics have ever been found. There is no evidence that Archaic people ever lived in these caves, and some of the caves are so difficult to get into that modern climbers would have to use ropes and hardware to do it. (Because there must be dozens, or even hundreds, of figurines yet to be discovered, the park service forbids exploration of the caves in the Redwall band, should anyone be bold enough to try.)

And yet no one knows why the figurines were made, although some kind of hunting magic has long been the leading hypothesis. Among those we saw in the museum collection were several that had separate twigs stuck into the bodies of the sheep or deer, like a spear or dart.

In a 2004 paper, Utah archaeologists Nancy J. Coulam and Alan R. Schroedl cite ethnographic parallels among such living hunter-gatherers as Australian Aborigines to argue that the figurines were fetishes used in a ritual of “increase magic,” and that they were the work not of individualistic shamans, but of a single clan, lasting 60 generations, that adopted the bighorn sheep as its totem. These hunters may have believed that the Grand Canyon was the place of origin of all bighorn sheep; by placing the figurines deep inside caves, under piles of rocks, they might have sought to guarantee the continued abundance of their prey. That the caves sometimes required very dangerous climbing to enter only magnified the magic.

Coulam and Schroedl’s theory is both bold and plausible, yet so little is known about the daily lives of the Archaic people in the Grand Canyon that we cannot imagine a way to test it. The figurines speak to us from a time before history, but only to pose a riddle.

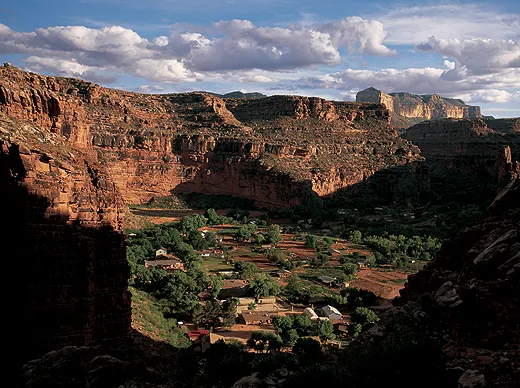

The riddles of the Grand Canyon are not confined to prehistoric times, either, as a trip among the present-day Havasupai makes clear. They live 2,000 vertical feet below the rim, on Havasu Creek. As an old trail plunges through four geologic layers, the reddish sandstone walls broaden to accommodate the ancient village of Supai in one of the most idyllic natural oases in the American West. A few miles upstream, one of the Grand Canyon’s most powerful springs sends a torrent of crystalline blue-green water down the ravine. (The people here call themselves Ha vasúa baaja, or “people of the blue-green water.”) The calcium carbonate that gives the creek its color renders it undrinkable, but the Havasupai draw their water from an abundance of other springs and seeps on the edges of their village.

By the time of their first contact with Europeans, as it happens in 1776, the Havasupai had long since adjusted to a seasonal round that defies logic but seems to have worked superbly for them. In spring, summer and early autumn they lived in the canyon, planting and harvesting. Then they moved back to the rim, where, at an altitude of more than 6,000 feet, they camped in the snow and spent the winter hunting and gathering.

With the coming of Anglo-Americans, that cycle of life changed. In 1882, after miners began gouging holes in the cliff walls in their quest for silver, lead and gold, the U.S. government restricted the Havasupai to the 518 acres of their village. From then on, they could no longer hunt or gather on the South Rim. Other Havasupai families lived in mid-canyon glades, such as Indian Gardens, the halfway point on today’s Bright Angel Trail. Gradually, however, they were nudged out by encroaching tourism.

As late as the 1920s, a park service employee called the Havasupai a “doomed tribe” amounting to “less than two hundred wretched weaklings.” But today, the Havasupai number some 650 men, women and children. And in 1974, Congress returned much of the people’s traditional land to them, in the largest restoration ever bestowed on a Native American tribe. The Havasupai Reservation today covers more than 185,000 acres, where, ironically, the tourists have become guests of the people of the blue-green water.

A number of those tourists come by helicopter; most hike in to Supai with light daypacks while Native wranglers bring their duffels on horseback or muleback. The chief draw for most visitors, however, is not the village, with its cornfields and pastures full of sleek horses, but three spectacular waterfalls downstream.

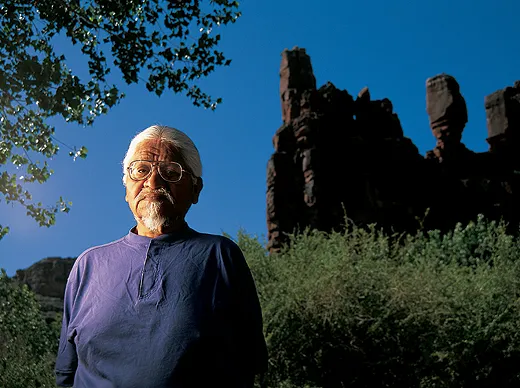

Bill, Greg and I backpacked the eight miles and 2,000 feet down into Supai, looking less for the Spring Break atmosphere of high tourist season than for a chance to plumb the past. On our second day, Rex Tilousi, who was then the tribal chairman, held our nosy questions at arm’s length for an hour or so, but then relented and took us on an amble through his boyhood neighborhood.

With his flowing silver hair, Colonel Sanders goatee and weather-beaten visage, Tilousi cut a striking figure. And his monologue blended sly satire with ancestral grievances. Referring to the miners, Tilousi recalled, “Here came the hairy man from the East, looking for the shining rock, wanting to get rich.” And then, more solemnly, “If it had been up to us, we never would have let the miners come down here.”

The tourist campground, built by the park service before 1974, lies “right on top of where we used to cremate our people,” Tilousi told us. “It disturbs me sometimes to see that campground, but we need income from the tourists.” He stroked his goatee and said, “Our ancestors lie there. Then the government said, ‘You can’t do that anymore.’ So now we have to bury our dead, just like everybody else.”

We paused beside a giant cottonwood as Tilousi pointed to a high cliff to the west. “See those two white marks up there?” Through binoculars I discerned a pair of white alkaline streaks made by seeping water in the ruddy cliff, seemingly inaccessible below the distant rim. “Those are two ears of corn, placed there by the Creator,” Tilousi said. “We pray to them, asking for plenty.”

The Havasupais’ welcome mat is something of a facade, Tilousi admitted. Archaeologists had asked Havasupai to interpret the “rock writings”—had even, he insisted, taken chisels to certain petroglyph panels—but the people had objected. “We feel we should never tell anyone besides ourselves” what the rock art means, he said. “We don’t know what you want to do with that knowledge.”

Visitors without guides are forbidden to explore the canyon beyond the main trail that leads down to the waterfalls, so the next day we hired two Havasupai in their mid-30s. Genial-faced Benjy Jones had the build of a sumo wrestler; Damon Watahomigie had less girth, a sharper mien and a fund of lore. We had hiked only 15 minutes when he stopped and pointed out a knob of rock far above us on the western rim. “See the frog?” he asked. The knob indeed looked like a frog preparing to jump.

“The story is that the people were living at Wi-ka-sala—Beaver Canyon, on your maps—when all the waters receded,” Watahomigie said. “Everything was dying because of the new age. We weren’t people then; we were animals and insects. The chief sent out the frog to find a place where we could begin again. The frog hopped all over, until he finally found this place. He could hear the Colorado River.”

We craned our necks, staring at the distant rock formation. “It was like Noah sending out the dove,” Watahomigie concluded.

Looking for rock art, we headed off the trail and up a steep slope choked with brush and cactus. Jones produced a leaf cradling an oily, dark red paste made from hematite, or iron oxide, a clay that Native Americans often used as a paint. One of the Havasupais’ most treasured substances, hematite from the canyon has been found east of the Mississippi River, traded prehistorically over more than a thousand miles.

Jones dipped his finger in the paste, then dabbed a streak on each of our boot soles. “Keeps the rattlesnakes away,” he explained.

As the day wheeled on, we crisscrossed the canyon, with our guides leading us to rock art panels and ruins that few visitors ever see. There were several our guides wouldn’t let us visit. “The ones that are closed, we aren’t supposed to bother them,” Watahomigie said. By “closed,” I assumed he meant having stone-slab doors intact.

His caution implies that the cliff buildings were the work of an earlier people. Archaeologists have debated Havasupai origins for half a century, strenuously and inconclusively. Some insist that a people called the Cohonina became the Havasupai. Others argue that the Havasupai, along with their linguistic cousins the Hualapai and Yavapai, are what they call Cerbat peoples, fairly recent migrants from the Great Basin of Nevada after a.d. 1350.

Like many other Native American peoples, the Havasupai usually say they have lived forever in the place they inhabit. But when we asked Tilousi how long his people had lived in the canyon of the blue-green water, he did not go quite that far. “I wasn’t here billions of years ago,” he said. “I can’t put numbers to the years that have gone by. I will just say, since the beginning of the ice age.”

On our last day in the Grand Canyon, Bill, Greg and I made a pilgrimage to a shrine deep in a little-traveled side valley that, like the Redwall caves guarding the split-twig figurines, had in all likelihood been an Archaic place of power.

As we wound down a faint trail across an increasingly barren landscape, I saw nothing that even hinted at a prehistoric presence—not a single potsherd or chert flake in the dirt, not the faintest scratchings on a wayside boulder. But when we entered a small gorge in the Supai Sandstone stratum, a deep orange cliff loomed on our left about 50 feet above the dry creekbed. Halfway up, a broad ledge gave access to a wall that severely overhung above it. We scrambled up to the ledge.

During the previous 20 years, I had found hundreds of rock art panels in backcountry all over the Southwest. I knew the hallmarks of the styles by which experts have categorized them—Glen Canyon Linear, Chihuahuan Polychrome, San Juan Anthropomorphic and the like. But the Shamans’ Gallery, as this rock art panel has been named, fit none of those taxonomic pigeonholes.

It was perhaps the most richly and subtly detailed panel I’d ever seen. Across some 60 feet of arching sandstone, vivid back-to-back figures were rendered in several colors, including two shades of red. Most of the figures were anthropomorphic, or human-shaped, and the largest was six feet tall.

Polly Schaafsma, a leading expert on Southwestern rock art, has argued that the Shamans’ Gallery (which she named) was painted before 1000 b.c., based on the style of the figures. She feels that it embodies the visionary trances of religious seers—shamans. The rock shelter where the artists recorded their visions, she believes, must have been a sacred site. Had these ancient artists been part of the troupe (or clan) that had climbed into the Redwall caves to hide split-twig figurines? We have no way of knowing and no foreseeable way of finding out.

But no matter. After two hours on the ledge, I stopped filling my notebook and simply stared. I tried to rid my mind of its Western, analytic itch to figure out what the paintings “meant” and surrendered to their eerie glory. In the presence of the Shamans’ Gallery, ignorance led to an unexpected kind of bliss.