Back To The Future

One of Washington’s most exuberant monuments—the old Patent Office Building —gets the renovation it deserves

On a recent afternoon in early spring, the old Patent Office Building in Washington, D.C. hosted a most distinguished reunion of American luminaries. Pocahontas leaned casually against one wall, resplendent in her lace collar and broad-brimmed hat. Nearby, a debonair Thomas Jefferson arched his eyebrows at the Mohawk chief Joseph Brant, while Sojourner Truth and Cinque, the Amistad rebel, conspired in the corner of the next room. Just upstairs, Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald cast languid glances toward Theodore Roosevelt, who scowled manfully in disdain.

Amid the estimable guests at this all-star cocktail party, construction crews and museum workers bustled about, putting the finishing touches on a project that had cost $283 million and lasted more than six years. After a meticulous, top-to-bottom renovation, the old Patent Office Building—newly rechristened the Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture—was nearly ready to reopen.

Pocahontas, Jefferson and the others were not present in flesh and blood, of course, but rather on painted canvases, lithographs and framed photos, many of them propped against the wall as they awaited rehanging after their long absence. The works form part of the permanent collection of the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery (NPG), which, together with the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), will return to its longtime home when the Reynolds Center officially opens on July 1.

It was oddly appropriate that the halls of this grand old building seemed thickly clustered with famous American ghosts. Over its life span of nearly two centuries, its stately porticoes have witnessed more history—wars, fires, inaugural balls, political scandals—than almost any other structure in the capital, and its marble corridors have felt the footsteps of memorable characters, including more than a few whose likenesses are enshrined there today.

Indeed, the two museums' most cherished historical and cultural treasure may well be the Patent Office Building itself. Although not the most famous monument in Washington, it is among the city's most eloquent. Begun in 1836, this Temple of Invention serves—now as then—as a place where citizens of the world can come and stand face to face with the proudest achievements of America's democratic culture. "This was always a showplace, a building that the government and the people saw as a symbol of American greatness," says SAAM director Elizabeth Broun.

This greatness was embodied not just in the Patent Office Building's contents—which have ranged over the years from Benjamin Franklin's printing press to Andy Warhol's silk screens—but by the building's architecture. In a manner more like a great European cathedral than most other American monuments, the Patent Office Building is the handiwork not of a single designer but of numerous architects and artisans—working across decades and even centuries. And each generation, from the early Republic through the Victorian era to the present, has, in a sense, reinvented the building afresh. "At every stage of its development, this was intended to be a building of the future," says NPG director Marc Pachter. "It was meant to be organic, optimistic, exuberant."

To be sure, the building has seen more than its share of difficulty and danger as well. Certain chapters of its history seem to exemplify the very worst aspects of Washington politics, as well as the hazards that visionary geniuses face when they work within a democratic culture. Yet the exuberant energy that Pachter describes was still evident on a recent visit, as workers hurried to touch up plasterwork, reset stone floors and install light fixtures in the gleaming new galleries. Crews of several hundred had been working almost round-the-clock for months.

"Each layer of the building tells part of its story," says Mary Katherine Lanzillotta, a supervising architect of the Hartman-Cox firm. She has come to know the structure intimately since she began working on plans for its renovation more than a decade ago. The process has—fittingly enough—brought the grand old building back in some respects to its beginnings, and to a destiny shaped when the country was still young.

In Pierre Charles L'Enfant's famous 1792 plan of Washington, three salient points immediately attract the eye. One is the Capitol, radiating a sunburst of diagonal avenues. The second is the "President’s House" and its grassy Ellipse. And the third is a projected building that stands directly between them, like the keystone in an arch, straddling Eighth Street Northwest between F and G streets, at the heart of what is now the capital city's downtown.

"Any other society would have known just what to do with this third point: they would have built a cathedral or a temple or a mosque," Pachter says. "Originally, L'Enfant proposed a nondenominational 'church of the republic,' an idea that was later modified into a pantheon of republican heroes, which would be the spiritual anchor of a secular state."

However, in the "City of Magnificent Intentions"—as Charles Dickens notoriously termed 19th-century Washington—that pantheon of heroes, like many other good ideas, never became a physical reality. (At least not until 1968, when the National Portrait Gallery first opened its doors.) Instead, the Eighth Street site remained another open space in a city of muddy avenues, squalid markets, noisome swamps. But then, in the 1830s, the Jacksonian Revolution began to remake the country—and with it the capital. For the first time in several decades, an ambitious federal building program was launched.

On the site of L'Enfant's proposed pantheon, the president and Congress determined to put a new Patent Office—a choice that might at first seem like a typically Washingtonian triumph of bureaucracy over poetry. Quite the contrary, however: the Patent Office would itself be the pantheon, albeit in the practical, hardheaded spirit of its age. As a showcase of American genius, it would extol the inventive, democratic, entrepreneurial energy of the Republic—itself still a new and not-quite-proven invention. The U.S. patent law then required inventors to submit scale models of their creations, which would be put on public display. "In this country, there were so few engineers and trained technicians that people needed models to refer to," says Charles J. Robertson, author of Temple of Invention, a new history of the Patent Office.

In the words of Congress, the structure would house a "national museum of the arts"—technology included—and "a general repository of all the inventions and improvements in machinery and manufactures, of which our country can claim the honor." A bill authorizing its construction passed on July 4, 1836—the 60th anniversary of American independence.

The man whom Andrew Jackson appointed as architect embodied many of the project's highest aspirations. A South Carolinian, Robert Mills had studied architecture at the elbow of no less than Thomas Jefferson, and styled himself the first professionally trained architect born in the United States. Mills was a prolific inventor and dreamer in the Jeffersonian mold, whose schemes—both realized and unrealized—included the Washington Monument, the nation's first elevated railroad, a canal system linking the Atlantic to the Pacific, and a plan to free the slaves in his native state and resettle them in Africa.

Mills was also a zealous patriot who found in architecture his own version of Manifest Destiny. "We have entered a new era in the history of the world," he exhorted his countrymen. "It is our destiny to lead, not to be led." He set about the Patent Office commission with characteristic zeal, and soon a Grecian temple was rising amid Eighth Street's boardinghouses and vegetable stands.

Indeed, Mills described the proportions of the main portico as "exactly those of the Parthenon of Athens." This was a highly symbolic choice. Public buildings previously constructed in Washington—particularly the Capitol—largely followed Roman models, evoking the oligarchic republic of Cato and Cicero. But by quoting the Parthenon, the Patent Office Building saluted the grassroots democracy of ancient Greece—a vision more in keeping with Jackson's own political ideals.

Though the Patent Office Building may have turned its face toward antiquity, it also embraced cutting-edge technology. Charged by Congress to render the structure fireproof, Mills devised an innovative system of masonry vaulting that elegantly spanned interior spaces without the aid of wood or iron. Dozens of skylights, hundreds of windows and a spacious central courtyard allowed most rooms to be illuminated by sunlight. Cantilevered stone staircases swept from floor to floor in graceful double curves.

Unfortunately for Mills, the Patent Office project would also come to embody some of the ugliest aspects of its era. President Jackson's enemies found the building a convenient symbol of "King Andrew the First's" grandiose egotism, and they missed no opportunity to undermine it. As the structure rose in stages through the 1830s and '40s, one Congressional investigation after another questioned Mills' competence, his expenditures and especially his cherished vaulting system, which was deemed dangerously unstable. Politicians compelled him to add supporting columns and tie rods, marring the pure lines of his original plan.

Egging on the anti-Jacksonians on Capitol Hill were some of Mills' fellow architects. A number of them—including Alexander J. Davis, Ithiel Town and William P. Elliot—had taken a hand in the Patent Office Building's early plans; scholars long debated which of these men deserves the most credit for its design. So the appointment of Mills as sole architect created resentments that festered for decades. "Mills is murdering the plans of the...Patent Office," wrote Elliot in a typical letter. "He is called the Idiot by the workmen."

Whether the charges were true, the attacks eventually found their mark: in 1851, after 15 years on the job, Mills was unceremoniously dismissed. (It is still painful to read the Secretary of the Interior's neatly penned letter informing Mills dryly that "your services in the character of Superintendent will...be no longer required.") The architect would die four years later at age 73, still fighting for reinstatement.

Today—better 150 years late than never—Mills has been vindicated: the just-completed renovations bring much of the building closer to his original scheme than it has been since the 19th century. His vaulted ceilings, still sturdy, shine with fresh plaster, applied using traditional methods. Cracked and missing pavers in his marble floors have been carefully replaced. Windows and skylights have been reopened. Layers of dull, federal-issue paint have been carefully steamed off, revealing original surfaces beneath.

And for the first time in living memory, partition walls have been cleared away, reopening interior spaces and allowing visitors to roam freely, as Mills intended, around all four sides of the central courtyard. Sunlight gleams along his austere corridors, beckoning you onward into both the future and the past.

Had you visited the Patent Office building in the 1850s—as nearly every Washington tourist of that day did—you would have been greeted by a hodgepodge of inventions, marvels and curiosities. In the grand exhibition hall in the south wing, display cases housed the Declaration of Independence, Andrew Jackson's military uniform and a piece of Plymouth Rock. Nearby were seashells, Fijian war clubs and ancient Peruvian skulls brought back by Lt. Charles Wilkes' expedition to the South Pacific, as well as souvenirs of Commodore Matthew Perry's then-recent visit to Japan. On the walls hung portraits of Revolutionary heroes and Indian chiefs. Many of these collections would later be transferred to the Smithsonian, forming the nucleus of the Institution's holdings in natural science, history and art.

If you had the stamina to continue, you would have found the patent models, tens of thousands of them. Here in facsimile were artificial limbs and teeth, coffins, beehives, sewing machines, telegraphs—all the quotidian proofs of American exceptionalism. In the corner of one dusty case, you might have noticed a contraption patented a few years before by an obscure Illinois congressman: an awkward-looking device for lifting a steamboat over shoals with inflatable airbags. Legend has it that later, when he became president, Abraham Lincoln enjoyed taking his young son Tad over to the Patent Office to show off his invention.

But before long, visitors to the building would encounter a very different sight. In February 1863, soon after the calamitous defeat of Union forces at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Walt Whitman wrote in his diary:

A few weeks ago the vast area of the second story of that noblest of Washington buildings was crowded close with rows of sick, badly wounded and dying soldiers....The glass cases, the beds, the forms lying there, the gallery above, and the marble pavement under foot—the suffering, and the fortitude to bear it in various degrees...sometimes a poor fellow dying, with emaciated face and glassy eye, the nurse by his side, the doctor also there, but no friend, no relative—such were the sights but lately in the Patent Office.

The gentle poet often visited this makeshift hospital by night, moving among the ranks of men and boys, comforting them, declaiming verses for them, scribbling their simple requests with a pencil in his notebook: "27 wants some figs and a book. 23 & 24 want some horehound candy."

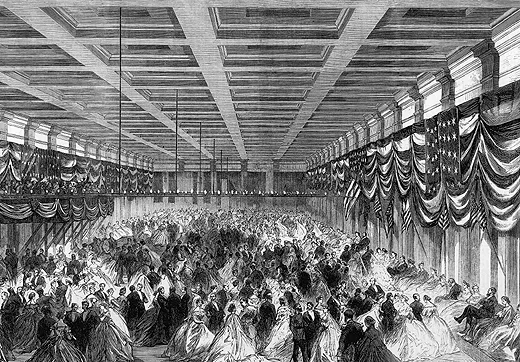

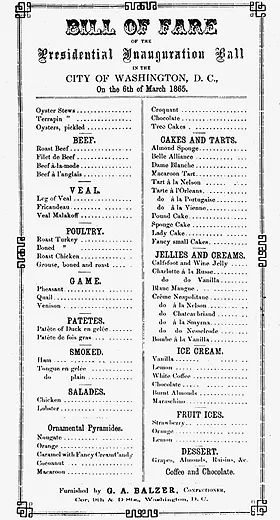

In the late winter of 1865, Whitman would return to the rooms he had described so vividly. This time, however, the building was filled not with the dead and dying, who had been moved elsewhere, but with bunting, banquet tables and confectionery. The Patent Office Building, which rarely hosted grand public occasions, had been chosen as the locale of Lincoln's second Inaugural Ball. This event, coming at a moment when the Confederacy's defeat was clearly imminent, became a chance for Washingtonians to cast away the cares of the past four years. Even Lincoln danced, and so exuberant was the celebration that when a buffet was served in a crowded third-floor corridor, much of the food ended up underfoot, with foie gras, roast pheasants and sponge cake trampled into the floor.

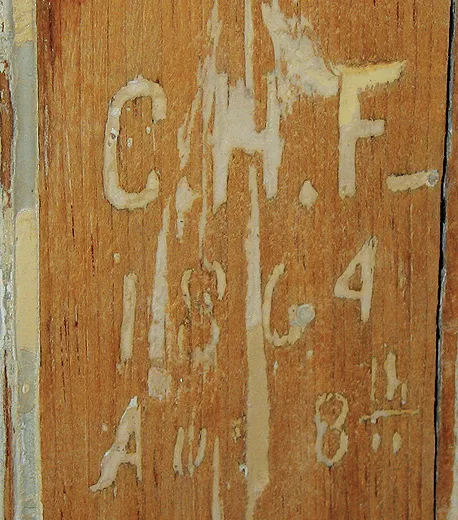

Down the hall in the east wing is the best-preserved of Robert Mills' grand public spaces, now known as the Lincoln Gallery. As part of SAAM, it will showcase contemporary works, including a giant flashing video installation by Nam June Paik. But its darker history has not been completely erased. During restoration, workers uncovered a faintly scratched graffito under layers of old paint on a window embrasure: "C.H.F. 1864 Aug. 8th." It is perhaps the last trace of an unknown soldier's sojourn here.

Not until after the Civil War was the immense building that Mills had envisioned finally completed. And it would not remain intact for very long.

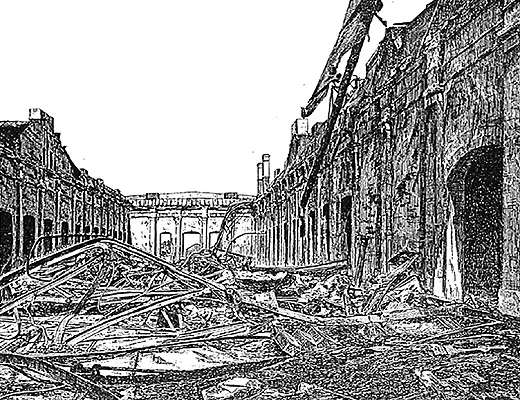

On the unseasonably chilly morning of September 24, 1877, some copyists working in the west wing ordered a fire lit in their office grate. Sparks landed on the roof and ignited a wooden gutter screen. Before long, half the building seemed to be in flames. "The scene was one of awful grandeur," reported the Evening Star's extra edition. "The cold, classic outline of the building was warmed up with a background of seething flame, curling, hissing, darting first here and there, taking no fixed course, but devouring everything within its reach." Although some 87,000 patent models were destroyed, a valiant effort by the Patent Office staff—and by fire companies from as far away as Baltimore—saved the most important artifacts. Still, the north and west wings stood as half-gutted shells. Mills had tried to make the building fireproof, but he could only go so far.

Ironically, although Mills' successor as architect, Thomas U. Walter, had been one of the harshest critics, claiming that Mills' vaulted ceilings would collapse in the event of fire, the conflagration actually consumed much of Walter's shallower, iron-reinforced vaulting, and left the earlier ceilings intact.

The task of rebuilding fell to a German-born local architect named Adolf Cluss, who in his youth, improbably enough, had been one of the chief political associates of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. By the 1870s, however, Cluss had left Communism far behind—and there was certainly no hint of proletarian revolution in his Patent Office designs. The cool austerity of the federal period would give way to a riot of lavish Victorian details—a style that Cluss termed "modern Renaissance"—not just in the west and north wing interiors, but also in Mills' undamaged Great Hall, which Cluss also remade, raising its ceiling. Faux-marbled walls flaunted portrait medallions of Franklin, Jefferson, Robert Fulton and Eli Whitney—a quartet of American inventors—while bas-relief goddesses of Electricity and Railroads smiled down from on high. Faceted stained-glass windows cast their dazzle across equally colorful floors of encaustic tile.

As part of the recent renovations, those walls, windows and floors have been meticulously restored for the first time since their creation. The floors proved a particular challenge; to set the thousands of replacement tiles the architects had to fly in a team of artisans from Hungary.

In an adjacent atrium, nearly as magnificent, Cluss lined the walls with tier upon tier of cast-iron balconies to hold patent models. This space, choked by partitioning in recent decades, has now been liberated again, and the balconies have been reclaimed to house the collections of the new Luce Foundation Center for American Art.

Cluss finished his work in 1885—and, unlike Mills, seems to have departed in good humor. He might have been less complacent, however, had he foreseen what lay in store for his handiwork. By the turn of the 20th century, the Patent Office Building—which now also housed the Department of the Interior—was seriously overcrowded, its grand spaces chopped up into offices. After 1932, when the U.S. Civil Service Commission took it over, fluorescent bulbs replaced the skylights, linoleum was laid over Mills' marble floors, and Cluss' magnificent walls were painted institutional green. A few years later, a street-widening project lopped off the monumental staircase from the south facade—leaving Mills' Parthenon looking, in the words of a critic, "like the end of a giant sliced sausage."

The final insult came in 1953. That year, Congress introduced legislation to demolish the whole Patent Office Building and, in the words of Marc Pachter, "replace it with that great monument of the American 1950s: a parking lot."

Luckily—as with the 1877 fire—quick-thinking rescuers saved the day. The nascent historic-preservation movement took up the cause of the much-abused edifice, and President Eisenhower was persuaded to intervene. Congress transferred the building to the Smithsonian. In 1968, the Portrait Gallery and the American Art Museum opened their doors in the newly remodeled Patent Office Building.

When the two museums closed for renovations in January 2000, they were expected to reopen in about three years. It turns out to have taken twice that long, but this delay—occasioned by the project's unforeseen complexity—proved a blessing. "I've come to believe that a lot of what's most spectacular and transformational has probably only occurred because we had more time to think," says SAAM's Elizabeth Broun. "I don’t think any of us fully appreciated the building before; its extraordinary character had been obscured under decades of well-intentioned additions and accretions. But then we had a moment of realization that we could liberate this building and let it resume the life that it had in the 19th century."

Prior to the renovations, both museums—installed not long after the damaging effects of the sun on artwork began to be fully understood—were deliberately kept dark, with many of the original windows closed off. Now, new glass that blocks harmful ultraviolet rays allows the daylight to pour in as Mills intended. "So 21st-century technology makes the 19th century more present," says Pachter.

The work has cost more than 100 times the Patent Office Building's original construction price of $2.3 million. The federal government has provided $166 million, while the rest has come from private donations. Much of the expenditure—on such things as a new heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning system—will be invisible to visitors.

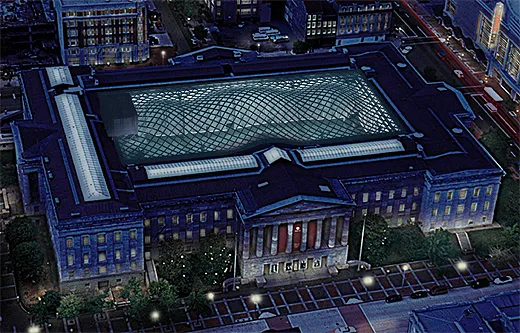

Perhaps the most dramatically visible elements of the whole construction project are yet to be seen. Plans are afoot to restore a version of Mills' demolished south facade staircase. And in the courtyard of the Patent Office Building, work is under way on an immense glass-and-steel canopy, designed by the renowned British architect Sir Norman Foster, which, when completed in 2007, will span the space in a single shimmering billow. It will be a gesture of vaulting ambition—both technical and aesthetic—that Robert Mills himself might well have admired. "We felt it wasn't betraying the building at all, but would bring in our own century's exuberance," Pachter says.

Adam Goodheart who last wrote about John Paul Jones for Smithsonian, is the C.V. Starr Scholar at Washington College.