Ancient Greece Springs to Life

Athens’ New Acropolis Museum comes to America in an exhibition highlighting treasures of antiquity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/the-New-Acropolis-Museum-631.jpg)

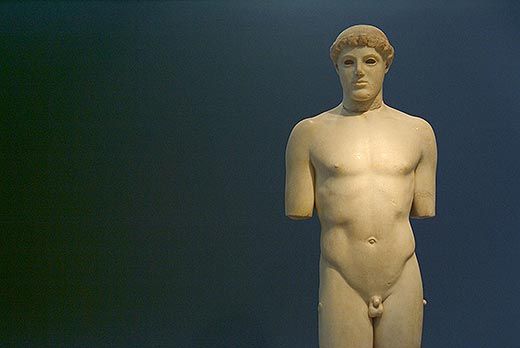

When the builders of the original Acropolis Museum first broke ground in Athens in 1865, archaeologists sifting through the rubble discovered a headless marble statue buried since the Persian Wars in the early fifth century B.C. Twenty-three years later, the head was identified and the world beheld one of the great treasures of antiquity, the Kritios Boy. Today the sculpture is on view in spectacular modern digs: the New Acropolis Museum, which opened to international fanfare on June 20, 2009, replacing its predecessor with a monumental space ten times the size.

The new museum houses a number of celebrated works from the Acropolis site, including roughly half of the Parthenon Marbles. (Most of the rest, known as the Elgin Marbles, remain in the British Museum in London; the works are the focus of the long-running dispute between Greece and the U.K. over repatriation.) Still, the 3-feet-10-inch–tall Kritios Boy, although dwarfed by the grandeur of the Parthenon, holds a special place in the history of art, pinpointing a momentous transition in the approach to human figuration—from the rigidly posed, geometrically balanced forms of the Archaic period to the more fluid, natural (yet still idealized) representations of the Classical era. Kritios Boy seems poised between life and death, eluding easy classification. “For some scholars, he is the end of Archaic sculpture; for others, he is the beginning of Classical sculpture,” says Ioannis Mylonopoulos, a specialist in ancient Greek art and architecture at Columbia University.

A cast of the original Kritios Boy will be among the artifacts displayed in an exhibition, “The New Acropolis Museum,” at Columbia’s Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery from October 20 to December 12. Mylonopoulos, the exhibition’s curator, who was born and raised in Athens, is beyond delighted that his campus office is just steps away from a masterwork he first encountered as an 8-year-old, when his parents felt it was time to take him up to the Acropolis. He now teaches a course devoted to the site, as well as a required core curriculum offering called Art Humanities that begins with a detailed, analytical study of the Parthenon. Both courses bring him joy. “I’m passionate about Archaic sculpture,” Mylonopoulos says, “so whenever I talk about the Kritios Boy I get high, so to speak.”

The stunning architecture of the New Acropolis Museum is a major focus of the Columbia exhibition, which traces the evolution of the project from original sketches to more sophisticated blueprints and models, culminating in full-blown digital images of the realized museum. “You will enter the exhibition room and be confronted—I think this is a great idea—with a work in process,” says Mylonopoulos.

Designed by the New York- and Paris-based Bernard Tschumi Architects (in collaboration with the Greek architect Michael Photiades), the museum sits at the foot of the Acropolis, creating a sort of visual dialogue between ancient and modern Greece. The building respects the street grid of Athens and echoes the tripartite classical program of base-midsection-conclusion, yet is filled with drama and surprise. On the lower level, which hovers atop hundreds of pillars, glass floors allow visitors to view the extensive archaeological excavation site beneath the museum; the double-height middle section houses a forest of artifacts unearthed at the Acropolis; and the glass-enclosed top floor, swiveled Rubik-like to align with the Parthenon itself, features the full length of that monument’s fabled marble frieze. Lost panels are left blank; those remaining in the British Museum are replicated in plaster, yet covered by a veil, in protest. “It’s impossible to stand in the top-floor galleries, in full view of the Parthenon’s ravaged, sun-bleached frame, without craving the marbles’ return,” New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff commented in a rave review of Tschumi’s ambitious project, which he called “mesmerizing” and “eloquent,” among other superlatives.

Having passed through the expansive Tschumi portion of the Wallach Gallery exhibition and another large space filled with artifacts from the Athens museum, visitors will come upon three small rooms dedicated to the pioneering Columbia architectural historian William Bell Dinsmoor (1886–1973), including papers from the university’s famed Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, which he directed from 1920 to 1926. Dinsmoor is revered by contemporary art historians at Columbia. “Everything I know about the Parthenon I learned from Dinsmoor and from teaching Art Humanities, which Dinsmoor was instrumental in developing,” says David Rosand, who holds the university’s Meyer Schapiro chair in art history and has taught there since 1964. Dinsmoor was also a consultant for the concrete replica of the Parthenon in Nashville, Tennessee (once called “the Athens of the West”), which opened in 1931.

“I studied Dinsmoor’s archive at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens,” says Mylonopoulos. “It’s unbelievable what this man was writing about architecture and art, which unfortunately remains unpublished. He was also an excellent epigrapher. He was brilliant at dealing with ancient Greek language and inscriptions.”

To Mylonopoulos, the Acropolis and the Parthenon are deeply personal. “It’s part of your life,” he says. “It’s as if you’re talking about your parents. You love them and they are always there. And you miss them the moment you don’t see them any more.” There’s more at stake than scholarly achievement or national pride, he says, “if you believe in freedom and democracy and the opening up of the human mind and spirit.”

“Athens was the place where all these came together, and if you accept the idea that the Parthenon is the culmination of these ideals, with all their faults—Athenian democracy is not our democracy, but the idea is there—then you realize it’s not about the monument,” he says. “It’s about the culture, it’s about the ideas, and it’s about the society behind this monument.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)