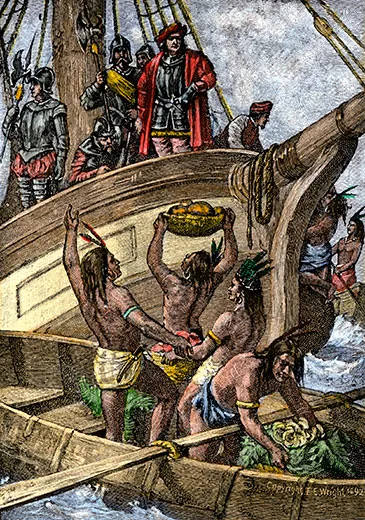

Alfred W. Crosby on the Columbian Exchange

The historian discusses the ecological impact of Columbus’ landing in 1492 on both the Old World and the New World

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Columbus-Exchange-New-World-arrival-631.jpg)

In 1972, Alfred W. Crosby wrote a book called The Columbian Exchange. In it, the historian tells the story of Columbus’s landing in 1492 through the ecological ramifications it had on the New World.

At the time of publication, Crosby’s approach to history, through biology, was novel. “For historians Crosby framed a new subject,” wrote J.R. McNeil, a professor at Georgetown University, in a foreword to the book’s 30th anniversary edition. Today, The Columbian Exchange is considered a founding text in the field of environmental history.

I recently spoke with the retired professor about “Columbian Exchange”—a term that has worked its way into historians’ vernacular—and the impacts of some of the living organisms that transferred between continents, beginning in the 15th century.

You coined the term “Columbian Exchange.” Can you define it?

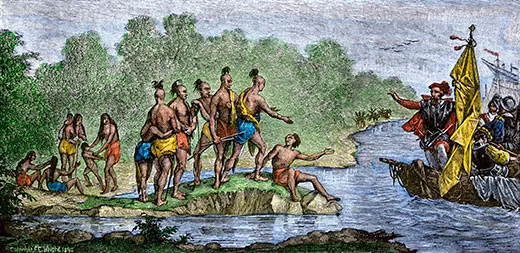

In 1491, the world was in many of its aspects and characteristics a minimum of two worlds—the New World, of the Americas, and the Old World, consisting of Eurasia and Africa. Columbus brought them together, and almost immediately and continually ever since, we have had an exchange of native plants, animals and diseases moving back and forth across the oceans between the two worlds. A great deal of the economic, social, political history of the world is involved in the exchange of living organisms between the two worlds.

When you wrote The Columbian Exchange, this was a new idea—telling history from an ecological perspective. Why hadn’t this approach been taken before?

Sometimes the more obvious a thing is the more difficult it is to see it. I am 80 years old, and for the first 40 or 50 years of my life, the Columbian Exchange simply didn’t figure into history courses even at the finest universities. We were thinking politically and ideologically, but very rarely were historians thinking ecologically, biologically.

What made you want to write the book?

I was a young American historian teaching undergraduates. I tell you, after about ten years of muttering about Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, you really need some invigoration from other sources. Then, I fell upon it, starting with smallpox.

Smallpox was enormously important until quite modern times, until the middle of the 20th century at the latest. So I was chasing it down, and I found myself reading the original accounts of the European settlements in Mexico, Peru or Cuba in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. I kept coming across smallpox just blowing people away. So I thought there must be something else going on here, and there was—and I suppose still is.

How did you go about your research?

It was really quite easy. You just have to be prepared somehow or other to notice the obvious. You don’t have to read the original accounts in Spanish or Portuguese. There are excellent English translations dating back for generations. Practically all of them will get into a page or two or ten about the decimation of American Indians, or a page about how important maize is when all European crops fail, and things like that. I really didn’t realize that I was starting a revolution in historiography when I got into this subject.

So, how were the idea and the book received at first?

That is kind of interesting. I had a great deal of trouble getting it published. Now, the ideas are not particularly startling anymore, but they were at the time. Publisher after publisher read it, and it didn’t make a significant impression. Finally, I said, “the hell with this.” I gave it up. And a little publisher in New England wrote me and asked me if I would let them have a try at it, which I did. It came out in 1972, and it has been in print ever since. It has really caused a stir.

What crops do you consider part of the Columbian Exchange?

There was very little sharing of the main characters in our two New World and Old World systems of agriculture. So practically any crop you name was exclusive to one side of the ocean and carried across. I am thinking about the enormous ones that support whole civilizations. Rice is, of course, Old World. Wheat is Old World. Maize, or corn, is New World.

The story of wheat is the story of Old World civilization. Thousands of years ago, it was first cultivated in the Middle East, and it has been a staple for humanity ever since. It is one of Europe’s greatest gifts to the Americas.

Maize was the most important grain of the American Indians in 1491, and it is one of the most important grain sources in the world right now. It is a standard crop of people not only throughout the Americas, but also southern Europe. It is a staple for the Chinese. It is a staple in Indonesia, throughout large areas of Africa. If suddenly American Indian crops would not grow in all of the world, it would be an ecological tragedy. It would be the slaughter of a very large portion of the human race.

Maize, potatoes and other crops are important not only because they are nourishing, but because they have different requirements of soil and weather and prosper in conditions that are different from other plants.

What ideas about domesticating animals traveled across the ocean?

American Indians were very, very roughly speaking the equal of Old World farmers of crops. But American Indians were inferior to the Old World raisers of animals. The horse, cattle, sheep and goat are all of Old World origin. The only American domesticated animals of any kind were the alpaca and the llama.

One of the early advantages of the Spanish over the Mexican Aztecs, for instance, was that the Spanish had the horse. It took the American Indians a little while to adopt the horse and become equals on the field of battle.

You talk about the horse being an advantage in war. What other impacts did the adoption of domesticated horses have on the Americas?

Horses not only helped in war but in peace. The invaders had more pulling power—not only horses but also oxen and donkeys. When you consider the great buildings of the Old World, starting with the Egyptians and running up through the ages, people in almost all cases had access to thousands of very strong animals to help them. If you needed to move a ton of whatever in the Old World, you got yourself an animal to help you. When you turn to the Americas and look at temples, you realize people built these. If you need to move a ton in the New World, you just got a bunch of friends and told everybody to pull at the same time.

What diseases are included in the Columbian Exchange?

The Old World invaders came in with a raft of infectious diseases. Not that the New World didn’t have any at all, but it did not have the numbers that were brought in from the Old World. Smallpox was a standard infection in Europe and most of the Old World in 1491. It took hold in areas of the New World in the early part of the next century and killed a lot of American Indians, starting with the Aztecs and the people of Mexico and Peru. One wonders how a few hundred Spaniards managed to conquer these giant Indian empires. You go back and read the records and you discover that the army and, just generally speaking, the people of the Indian empires were just decimated by such diseases as smallpox, malaria, all kinds of infectious diseases.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)