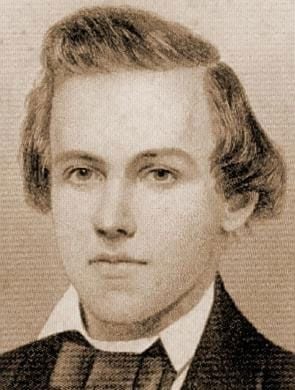

A Chess Champion’s Dominance—and Madness

As a young man, Paul Morphy vanquished eight opponents simultaneously while effectively blindfolded

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111212032554Young-Paul-Morphy-chess-prodigy.jpg)

By the time Paul Morphy was felled by a stroke on July 10, 1884, he had become an odd and familiar presence on Canal Street in New Orleans: a trim little man in sack suit and monocle, muttering to himself, smiling at his own conceits, swinging his cane at most who dared approach. Sometimes he would take a fancy to a passing woman and following her for hours at a distance. He lived in fear of being poisoned, eating only food prepared by his mother or sister, and he believed that neighborhood barbers were conspiring to slit his throat. His family tried to have him committed to an asylum, but he argued his sanity so convincingly that the authorities declined to admit him. It had been a quarter-century since he became a world-renowned chess champion, and for the last decade of his life he was loath to discuss the game at all.

No one could say with certainty what prompted Morphy’s slow decline, but the discovery of his genius in 1846 remained legendary. Morphy, at age 9, was sitting on his family’s back porch as his uncle and father, a justice on the Louisiana State Supreme Court, played chess. After several hours, the men declared the match a draw and moved to sweep away the pieces. Morphy stopped them. “Uncle,” he said, “you should have won that game.” He maneuvered the pieces and explained: “Here it is: check with the rook, now the king has to take it, and the rest is easy.” And he was right.

Soon afterward, Major General Winfield Scott, who had a reputation as a skilled player, stayed in New Orleans for five days while he was en route to the Mexican War. He asked an acquaintance at the chess club on Royal Street to find him a worthy opponent, and at eight o’clock that evening Scott found himself sitting across from Morphy, who wore a lace shirt and velvet knickerbockers. Scott, believing he was the victim of a prank, arose in protest, but his friends assured him that Morphy was no joke. He checkmated Scott in ten moves.

Morphy had an astounding memory, capable of recording every factor he deemed pertinent to his play—openings, defenses, even entire games—but he also had an intuitive grasp of the possibilities. He could visualize the board several plays deep, anticipating and capitalizing on even the slightest misstep. “The child had never opened a work on chess,” wrote Morphy’s uncle, Ernest Morphy, to the editor of chess magazine La Régence, which published one of Morphy’s early games. “In the openings he makes the right moves as if by inspiration, and it is astonishing to note the precision of his calculations in the middle and end game. When seated before the chessboard, his face betrays no agitation even in the most critical positions; in such cases he generally whistles an air through his teeth and patiently seeks for the combination to get him out of trouble.” The prodigy next took on Johann J. Lowenthal, a political refugee from Hungary who was well known in European chess circles. Morphy, in his French vernacular, described Lowenthal’s reaction at losing to him in one word: “comique.”

In 1850, Morphy registered at Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama. He was elected president of the Thespian Society during his freshman year and played Portia in The Merchant of Venice. He abhorred sports and tried to compensate for his slight, 5-foot-4 frame by briefly studying fencing. He played no chess in his college years, other than a few games with classmates in the summer of 1853. For his thesis he chose to write about war, a subject that, according to one acquaintance, “he brought within very narrow limits the conditions that make it justifiable. The logic of his argument would exclude forcible secession, and whether in play or in life Morphy was severely logical, even to a fault. But such a course brought consequences that preyed upon his mind.”

After graduation he returned to New Orleans and enrolled at the University of Louisiana. He earned a law degree in 1857 but was legally obliged to wait until his 21st birthday to begin his career as an attorney. In the meantime he returned to chess, a decision that had less to do with any great passion for the game than with a fervent ambition to defeat the best players of the United States and Europe. “He felt his enormous strength,” said Charles Maurian, a childhood friend, “and never for a moment doubted the outcome.”

Morphy entered the First American Chess Congress, held on October 5, 1857 at the New York Chess Club. He won his first game in 21 moves, almost in a matter of minutes—and this in an era with no time limit, when players pondered for hours and games lasted for days. His only true competitor was a German immigrant named Louis Paulsen, who exasperated Morphy by taking as long as 75 minutes on a move and beating him at their third game. Before the sixth game, Morphy dined with fellow player William James Appleton Fuller. “His patience was worn out by the great length of time Paulsen took for each move,” Fuller recalled. “His usually equable temper was so disturbed that he clenched his fist and said, ‘Paulsen shall never win another game from me while he lives.’” Morphy beat him five times and won the competition, then spent the next month in New York being feted like a king.

He set his sights on Howard Staunton, an Englishman and arguably the most respected player in Europe. On Morphy’s behalf, the New Orleans Chess Club raised a purse of $5,000 and invited Staunton to visit the city for a match, promising him $1,000 for expenses if he lost. He declined, on the ground that New Orleans was too far away. Morphy planned a trip to England, intending to enter a tournament in Birmingham and challenge Staunton on his own turf, where he couldn’t refuse. But when he reached the city he learned that the tournament had been postponed for two months.

He stayed anyway and joined forces with Frederick Milnes Edge, a flamboyant newspaperman who began acting as Morphy’s publicity agent. Edge stirred up controversy by accusing Staunton of cowardice in the press. Staunton, who was the chess editor of the Illustrated London News, responded by suggesting that Morphy was an adventurer without the financial backing he claimed and, worse, that he was a professional, not a gentleman. Morphy tried for three months to arrange a match with Staunton but gave up in October 1858. “Permit me to repeat,” Morphy wrote in his last letter to him, “that I am not a professional player; that I never wished to make any skill I possess the means of pecuniary advancement, and that my earnest wish is never to play for any sake but honor.”

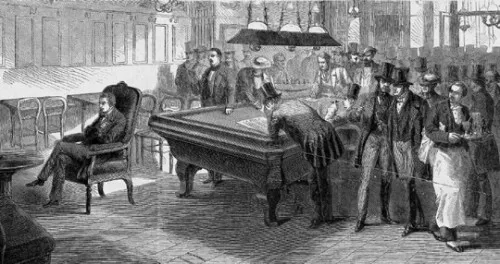

Morphy set sail for Paris, where he won a “blindfold” tournament: He sat in one room of the Café de la Regence while his eight opponents sat in another. The opponents had the chess boards, along with several other players who could give them advice; Morphy simply faced a bare wall and called out his moves in loud, clear, flawless French. He played for 10 hours, with no food or drink, and beat them all. “He was shaken by the hand and complimented till he hung down his head in confusion,” the New York Times reported. “Such a mind never did exist, and, perhaps, never will again.”

Morphy returned to New Orleans an international celebrity but settled into a strangely subdued mood; he said he hadn’t done as well as he should have. He finally embarked on a law career, but interrupted it at the outbreak of the Civil War. He opposed secession, and felt torn between his loyalties to the Union and to Louisiana, but he journeyed to Richmond to see Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, a family friend, about the possibility of securing a diplomatic position. Some accounts suggest that he served as a volunteer aid to Beauregard (even gathering intelligence for the Confederates during the First Battle of Manassas), but others say the general deemed Morphy unqualified to serve, on or off the battlefield.

He spent the next few years traveling, first to Havana and then to Europe, staying in Cadiz and Paris and declining numerous invitations from chess clubs. To his friend Daniel Willard Fiske he confessed “intense anxiety” about the war raging back home. “I am more strongly confirmed than ever in the belief that the time devoted to chess is literally frittered away,” Morphy wrote. “I have, for my own part, resolved not to be moved from my purpose of not engaging in chess hereafter.” He returned to New Orleans in November 1864 and opened a law office, only to close it after a few months—prospective clients seemed more interested in talking about chess than about their cases. He tried again several years later and had the same frustration.

He began seeing evil intentions where there were none. As late as 1878 he continued to receive invitations to compete, but he played chess very rarely and never publicly, and usually out of some imagined desperation. Once Morphy entered the office of a prominent resident of New Orleans and said he needed $200 to ward off impending disaster. The man, an old friend, decided to test the strength of both Morphy’s delusion and his aversion to chess.

“You want this money very much, it seems,” he said.

“Yes,” Morphy replied. “I must have it—it is absolutely necessary.”

“Well, I’ll tell you what I will do: if you will play a game of chess with me, I will make it two hundred and fifty dollars.”

Morphy thought about it, exhibiting a “disdainful curl of the lip and manifest repugnance.” Finally he agreed, and a chessboard was set upon the desk. Morphy allowed his friend to beat him in a few moves.

“There!” the former champion exclaimed. “I have done what you require, but the next time I play chess with you, I will give you the queen!” He turned to leave.

His friend called out, reminding him that he was forgetting his reward.

“I will come for it tomorrow!” Morphy promised. But he never did.

Sources

Books: David Lawson, Paul Morphy: The Pride and Sorrow of Chess. New York: McKay, 1976; William Ewart Napier, Paul Morphy and the Golden Age of Chess. New York: McKay, 1957; C.A. Buck, Paul Morphy: His Later Life. Newport, KY: Will. H. Lyons, 1902; Frederick Milnes, Paul Morphy, the Chess Champion. New York: Appleton, 1859.

Articles: “Paul Morphy Dead: The Great Chess Player Insane.” New York Times, July 11, 1884; “Letter from Paul Morphy to Mr. Staunton, of England.” New York Times, November 1, 1858; “Our Foreign Correspondence: Paris.” New York Times, October 19, 1858.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen-abbot-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen-abbot-240.jpg)