A Brief History of the Teleprompter

How a makeshift show business memory aid became the centerpiece of modern political campaigning

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Teleprompter-U1446189-631.jpg)

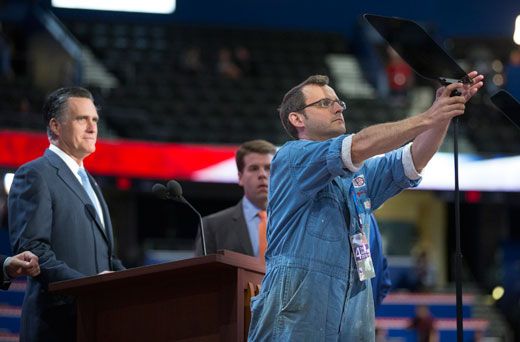

As President Barack Obama and former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney enter the home stretch of their campaigns, they've now been touring the country and delivering the same stump speech three times per day for the past ten months straight. Both of the candidates read their words while looking out at the crowds, instead of down at a piece of paper, conveying the idea that they’ve memorized their speeches and are connecting with their audiences. And while conservatives take great pleasure in mocking President Obama’s reliance on a machine to help him deliver his speeches, the truth is that both candidates—along with politicians for more than a generation—read off of thin, nearly invisible plates of glass angled at a 45-degree slant at either side of their podiums. Perhaps more than any other technological advance—more than the touch-screen voting booth, the automated campaign phone call or even the slick TV attack ad—the teleprompter continues to define our political age.

The device started out in 1948 as a roll of butcher paper rigged up inside half of a suitcase. Actor Fred Barton Jr., a Broadway veteran, was nervous. “For those that had been either in theater or the movies, the transition to television was difficult, because there was a much greater need for memorizing lines,” says Christopher Sterling, a media historian at George Washington University. “At the time, there was a lot more live television, which many people today tend to forget.” Instead of memorizing the same batch of lines over the course of months, Barton was now expected to memorize new lines on a weekly or even daily basis. Cue cards were sometimes used, but relying on unsteady stagehands to flip between them could sometimes cause catastrophic delays.

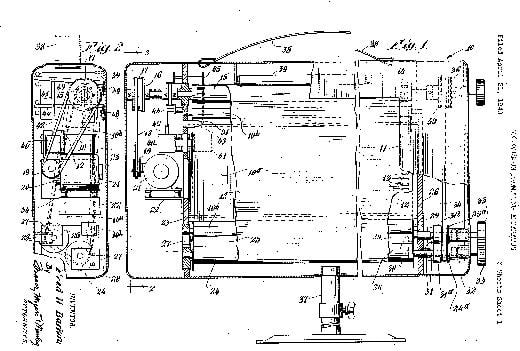

Barton went to Irving Kahn, a vice president at 20th Century Fox studios, with the idea of connecting cue cards in a motorized scroll, so he could rely on prompts without risking an on-screen blunder. Kahn brought in his employee Hubert Schlafly, an electrical engineer and director of television research, and asked him if it could be done. “I said it was a piece of cake,” Mr. Schlafly told the Stamford Advocate in 2008. Using half of a suitcase as an outer shell for his new device, he rigged up a series of belts, pulleys and a motor to turn a scroll of butcher paper that displayed an actor’s lines in half-inch letters. The paper was turned gradually, as controlled by a stagehand, while the words were read.

On April 21, 1949, Schlalfly submitted a patent application for his “television prompting apparatus,” and in the tradition of offstage “prompters” who had been relied upon to feed forgotten lines to actors, he called his device the TelePrompTer. When the application was approved, the New York Times noted that it “coaches television actors into letter-perfect delivery of their lines and permits news commentators to simulate prodigious feats of memory.” It may have seemed unlikely at the time, but a new political age was born.

Although Schlafly, Barton and Kahn pitched the device to 20th Century Fox, the company was not interested. They promptly quit the company and started their own, founding the TelePrompTer Corporation. At first, the machine was used for its intended purpose: televised entertainment. It was part of a live production for the first time on December 4, 1950, as actors in the CBS soap “The First Hundred Years” read their lines off a device mounted to the side of the camera. “Initially, it was either above or below the lens of the camera, or to the right or the left, so you could always tell, unfortunately, because you could see the person's eye was slightly off,” Sterling says.

Quickly, others saw just how useful teleprompters could be—and as they began adding their own refinements, the term itself became a generic catchall for all sorts of automatic prompting devices. The TelePrompTer Corporation kept making their product, but many others began designing their own versions. Jess Oppenheimer, the producer of “I Love Lucy,” took out a patent for the first in-camera teleprompter, which used a system of mirrors and glass to project the script directly in front of the lens. “Once you could literally shoot through the teleprompter, the on-screen talent was looking straight at the audience,” Sterling says. “Home viewers saw a smoother presentation, with a hell of a lot more eye contact.” Soon, broadcast news operations started using the machine, replacing the printed scripts anchors had previously held in their hands, starting at the network level and then filtering down to local markets.

By the time the next presidential election rolled around, in 1952, Kahn saw the next frontier for his device. After reading that aging former President Herbert Hoover had had difficulty reading speeches while campaigning for Gen. Dwight D. Eiseinhower, Kahn traveled to Chicago, the host city for the Republican National Convention, and persuaded Hoover and other speakers to try out the machine. The technology was an immediate hit—between that convention and the Democratic gathering later that month, 47 of the 58 major speeches were teleprompted. Two months later, though, candidate Eisenhower gave the technology an inadvertent publicity boost that allowed it to become legendary.

Describing a September 9, 1952, campaign speech by Eisenhower in Indianapolis, the New York Times wrote, “General Eisenhower, who was speaking with the aid of a Teleprompter, a device that unreels the speaker’s text, was heard by a national radio audience, but not those in the hall, to say this: ‘Go ahead! Go ahead! Go ahead! Yah, damn it, I want him to move up.’” The outburst was reprinted in thousands of press accounts nationally, letting the world know about the new invention. Later, Eisenhower told reporters he didn’t have the “slightest memory” of having said what was then considered a strong curse word, but apologized nonetheless. (This story has previously been attributed to Hoover at the Republican convention—sourced from a quote by Schlafly—but no contemporary reports of that incident exist, suggesting that Schlafly merely mixed up the names of two of the most prominent Republican politicians of the era.)

Whatever the details of the episode, by the end of the 1952 election season, both parties had obviously grasped the importance of the device. Its heavy usage also reflected a broader shift in political procedure, as conventions morphed from gatherings of delegates to pick a president to slickly produced days-long television advertisements for previously selected candidates. Coinciding with the explosive penetration of TV into American households, the teleprompter soon became a staple of political campaigning and speechmaking, used for a State of the Union address for the first time in 1954 by Eisenhower himself. As the Associated Press wrote in 1956, describing how in-demand Kahn and others from the TelePrompTer Corporation suddenly were at both parties’ conventions, “If you build a better teleprompter, the whole world, including the president’s cabinet, will beat a path to your door.”

“What the teleprompter did was increase the ability of the speaker to relate to the audience,” says Kathleen Hall Jamieson, an expert on political communication and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. “There is a sense in which the speaker is communicating directly with you, when talking to the camera.” Rather than continually glancing down at a printed script, showing audiences the top of their heads, speechmakers could use the machine to convey that they were simply talking extemporaneously, straight from the heart.

Of course, at the time, the machine itself was bulky and utterly apparent to in-person audiences—TV cameras at the 1952 GOP convention reportedly agreed to intentionally cut it out of the frame when filming so as to preserve the aura of authenticity. Starting in the 1960s, this issue was solved, to some degree, by reflecting printed text onto angled slabs of thin glass on either side of the podium—the side-by-side teleprompters we’re familiar with today. “Once the side-by-side teleprompter was developed, speakers could also maintain eye contact with the crowd, because they could scan from side to side, from left to right,” Jamieson says.

This formula for creating a seemingly authentic air of spontaneity, Jamieson notes, has generated a paradoxical side effect. “When you’re reading off side-by-side teleprompters, the pacing of the speech changes, because you’ve got to switch from teleprompter to teleprompter as the scroll moves.” As a result, she says, “we hear a discernible teleprompter cadence,” a ‘line-pause-line’ rhythm that has penetrated political speechmaking to degree that we rarely even think about it. Additionally, the alternating pattern leads speakers to move their heads left and right as they switch form screen to screen, as though they’re watching a ball hit back-and-forth during a tennis match.

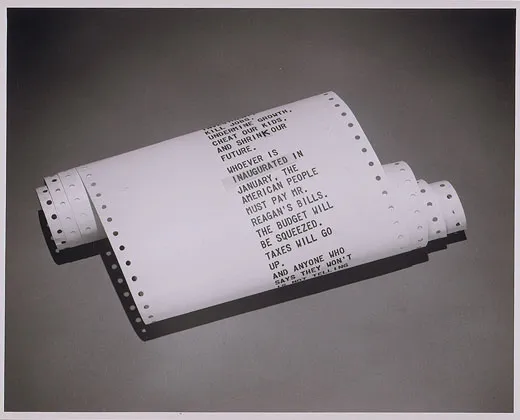

Over the years, subtle advances in teleprompter technology continued. Into the early ’80s, the text was typically still printed on pieces of paper—the National Museum of American History has the teleprompter text of Walter Mondale’s 1984 Democratic National Convention nomination acceptance speech where he notoriously admitted “Mr. Reagan will raise taxes, and so will I. He won’t tell you. I just did.”

Starting in 1982, though, when Hollywood sound mixer and stagehand Courtney M. Goodin created Compu=Prompt—a software-based system that projected text from a modified Atari 800 PC—computers began to displace printed scrolls across the industry. Computerized systems held several advantages, including the fact that text could be edited and loaded at the last second. Still, in rare instances, technical difficulties with software have forced speechmakers into thinking on their feet. For Bill Clinton’s 1994 State of the Union Address, the machine was loaded with the wrong speech, so he began his live speech off-the-cuff and from memory until the correct text appeared.

Most recently, voice-recognition software has allowed for systems that automatically scroll text based on the speaker’s actual rate of speech. These are now commonly used in newscasts and other broadcasts—but for crucial political speeches, the importance of an ideal scrolling rate leads both parties to rely upon manual scrolling. “You’re a slave of the teleprompter,” Jamieson says. “If someone scrolls too rapidly, you sound completely unnatural, but if they scroll too slowly, you sound as if you're drunk.”

Nowadays, political campaigning—especially national conventions—is built entirely around the machines, says National Museum of American History curator Larry Bird, who’s attended every Democratic and Republican convention since 1984. “Everything is put onto that device, even the national anthem and the Pledge of Allegiance,” he says. “It’s really become the symbol, to my way of thinking, of the completely canned television spectacle.” (Of course, there are exceptions: “This year, when Clint Eastwood came out and did his routine, the thing wasn’t even on,” Bird says.)

Despite the remarkable journey of his invention from makeshift line prompter to the ubiquitous centerpiece of every campaign, for the vast majority of his life, Hubert Schlafly never had the experience of using a teleprompter himself. Shortly before he died last year, though, he finally tried it out, when he was inducted into the Cable Television Hall of Fame in 2008. As he stood on stage, his 88-year-old voice straining, he read his speech, repeatedly shifting back and forth, left and right.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)