1968 Democratic Convention

The Bosses Strike Back

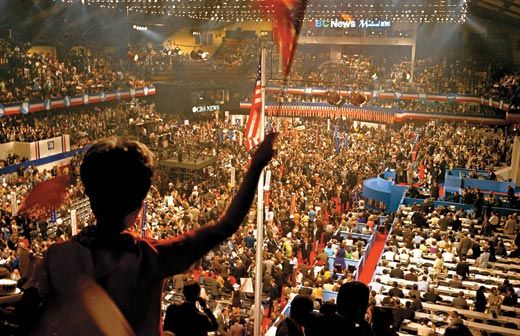

As delegates arrived in Chicago the last week of August 1968 for the 35th Democratic National Convention, they found that Mayor Richard J. Daley, second only to President Lyndon B. Johnson in political influence, had lined the avenues leading to the convention center with posters of trilling birds and blooming flowers. Along with these pleasing pictures, he had ordered new redwood fences installed to screen the squalid lots of the aromatic stockyards adjoining the convention site. At the International Amphitheatre, conventioneers found that the main doors, modeled after a White House portico, had been bulletproofed. The hall itself was surrounded by a steel fence topped with barbed wire. Inside the fence, clusters of armed and helmeted police mingled with security guards and dark-suited agents of the Secret Service. At the apex of the stone gates through which all had to enter was a huge sign bearing the unintentionally ironic words, "HELLO DEMOCRATS! WELCOME TO CHICAGO."

If this Potemkin village setting weren't enough to intensify anxiety among Democrats gathering to nominate their presidential candidate, the very elements and conditions of Chicago life contributed to a sense of impending disaster. The weather was oppressively hot and humid. The air conditioning, the elevators and the phones were operating erratically. Taxis weren't operating at all because the drivers had called a strike before the convention began. The National Guard had been mobilized and ordered to shoot to kill, if necessary.

Even as delegates began entering this encampment, an army of protesters from across the country flowed into the city, camping in parks and filling churches, coffee shops, homes and storefront offices. They were a hybrid group—radicals, hippies, yippies, moderates—representing myriad issues and a wide range of philosophies, but they were united behind an encompassing cause: ending the long war in Vietnam and challenging Democratic Party leaders and their delegates to break with the past, create change—yes, that was the term then on every protester's lips—and remake the battered U.S. political system. As Rennie Davis put it, speaking as project director for the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, the largest and most important group for the planned protests: "Many of our people have already gone beyond the traditional electoral processes to achieve change. We think that the energies released...are creating a new constituency for America. Many people are coming to Chicago with a sense of new urgency, and a new approach."

What followed was worse than even the most dire pessimist could have envisioned.

The 1968 Chicago convention became a lacerating event, a distillation of a year of heartbreak, assassinations, riots and a breakdown in law and order that made it seem as if the country were coming apart. In its psychic impact, and its long-term political consequences, it eclipsed any other such convention in American history, destroying faith in politicians, in the political system, in the country and in its institutions. No one who was there, or who watched it on television, could escape the memory of what took place before their eyes.

Include me in that group, for I was an eyewitness to those scenes: inside the convention hall, with daily shouting matches between red-faced delegates and party leaders often lasting until 3 o'clock in the morning; outside in the violence that descended after Chicago police officers took off their badges and waded into the chanting crowds of protesters to club them to the ground. I can still recall the choking feeling from the tear gas hurled by police amid throngs of protesters gathering in parks and hotel lobbies.

For Democrats in particular, Chicago was a disaster. It left the party with scars that last to this day, when they meet in a national convention amid evidence of internal divisions unmatched since 1968.

To understand the dimensions of the Democrats' calamity, recall that in 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson had defeated Barry Goldwater for the presidency with 61.1 percent of the popular vote, a margin eclipsing even the greatest previous electoral victory, by Franklin D. Roosevelt over Alf Landon in 1936. In mid-1964, passage of civil rights legislation had virtually ended legal segregation in America. Optimists had begun talking about America's entering a "golden age."

By that next summer, however, the common cause of blacks and whites marching together had been shattered as riots swept the Watts section of Los Angeles and, over the next two years, cities across the country. In that same initially hopeful year, the Johnson administration had made a fateful commitment to keep increasing the numbers of troops to fight a ground war in Vietnam, an escalation that would spawn wave upon wave of protest. In the 1966 congressional elections, Democrats—who had been experiencing the greatest electoral majorities since the New Deal—sustained severe defeats.

As 1968 began, greater shocks awaited the nation: North Vietnamese forces launched the Tet offensive that January, rocking U.S. troops and shattering any notion that the war was nearly won. Johnson withdrew from the presidential campaign that March. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis in early April, and another succession of riots swept the cities. Robert F. Kennedy, heir to the Kennedy legacy, had his presidential campaign cut down by an assassin's bullet after winning the critical California primary in June.

It was against this extraordinarily emotional background that the Democrats convened. Hubert H. Humph- rey, LBJ's vice president, had sat out the primaries but secured delegates controlled by the party establishment. Senator Eugene McCarthy—the antiwar candidate whose strong second-place showing in the New Hampshire primary had demonstrated Johnson's vulnerability—had abundant forces in the hall, but they were now relegated to the role of protesters. Senator George S. McGovern had rallied what remained of Kennedy's forces, but he, too, knew he led a group whose hopes had been extinguished.

From whatever political perspective—party regulars, irregulars or reformers—they all shared an abiding pessimism over their prospects against a Republican Party that had coalesced behind Richard M. Nixon. They gave voice to their various frustrations in the International Amphitheatre during bitter, often profane, floor fights over antiwar resolutions. The eventual nomination of Humphrey, perceived heir to Johnson's war policies, compounded the sense of betrayal among those who opposed the war. The bosses, not the people who voted in the primaries, had won.

The violence that rent the convention throughout that week, much of it captured live on television, confirmed both the Democrats' pessimism and the country's judgment of a political party torn by dissension and disunity. In November the party would lose the White House to Nixon's law-and-order campaign. In the nine presidential elections since, Democrats have won only three, and only once—in 1976, after the Watergate scandal forced Nixon to resign in disgrace—did they take, barely, more than 50 percent of the votes.

Changes in party rules have curtailed the establishment's power to anoint a presidential nominee, but the ideological divides have persisted; thus this year's rival candidates battled bitterly to win state primaries. And after such a divisive primary season, in the end the nomination still depended on the "superdelegates" that replaced the party bosses.

One 1968 memory remains indelible 40 years later. Throughout that week I had been a guest commentator on NBC's "Today" show, broadcasting live from Chicago. Early Friday morning, a few hours after the convention ended, I took the elevator to the lobby of the Conrad Hilton Hotel, where I had been staying, to head for the studio. As the elevator doors opened, I saw huddled before me a group of young McCarthy volunteers. They had been bludgeoned by Chicago police, and sat there with their arms around each other and their backs against the wall, bloody and sobbing, consoling one another. I don't know what I said on the "Today" show that morning. I do remember that I was filled with a furious rage. Just thinking of it now makes me angry all over again.

Haynes Johnson, who has written 14 books, covered the 1968 Democratic National Convention for the Washington Star.