1912 Republican Convention

Return of the Rough Rider

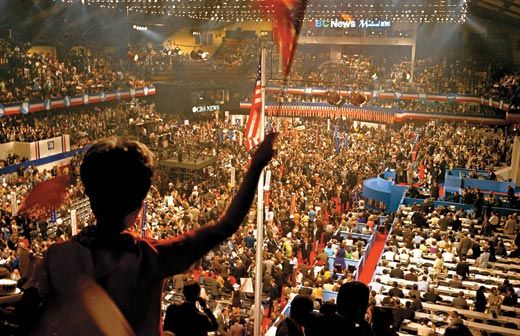

William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt had once been friends. But when the Republican Party met in Chicago to choose its presidential candidate in June 1912, the nomination battle between the two men was brutal, personal—and ultimately fatal to the party's chances for victory in November. Taft declared Roosevelt to be "the greatest menace to our institutions that we have had in a long time." Roosevelt saw Taft as the agent of "the forces of reaction and of political crookedness." The resulting floor fight in the aptly named Chicago Coliseum lived up to the prediction of the Irish-American humorist Finley Peter Dunne that the convention would be "a combynation iv th' Chicago fire, Saint Bartholomew's massacree, the battle iv th' Boyne, th' life iv Jesse James, an' th' night iv th' big wind."

For years, the tensions within the Grand Old Party had been building over the issue of government regulation. During his presidency, Roosevelt had advocated a "Square Deal" between capital and labor in American society. By the time he left the White House in March 1909, Roosevelt believed that the federal government must do more to supervise large corporations, improve the lot of women and children who worked long hours for low wages in industry, and conserve natural resources. "When I say that I am for the square deal, I mean not merely that I stand for fair play under the present rules of the game, but that I stand for having those rules changed so as to work for a more substantial equality of opportunity and of reward for equally good service," he said in August 1910. Roosevelt was especially critical of the state and federal courts for overturning reform legislation as unconstitutional, and he said that such decisions were "fundamentally hostile to every species of real popular government."

Roosevelt's burgeoning crusade for more active government reflected his loss of faith in William Howard Taft, whom the former Rough Rider had chosen as his successor. As president, Taft had sided with the conservative wing of the party, which had opposed Roosevelt's reforms at every turn. For his part, Taft believed Roosevelt had stretched the power of the executive branch too far. As a lawyer and former federal judge, Taft had nothing but disdain for his predecessor's jaundiced view of the judiciary. "The regret which he certainly expressed that the courts had the power to set aside statutes," wrote the president, "was an attack upon our system at the very point where I think it is the strongest."

Tensions deepened in 1912, when Roosevelt began advocating the recall of judicial decisions through popular vote. With the courts tamed as an enemy to reform, Roosevelt then would press forward "to see that the wage-worker, the small producer, the ordinary consumer, shall get their fair share of the benefit of business prosperity." To enact his program, Roosevelt signaled that he would accept another term as president and seek the nomination of the Republican Party.

These ambitions revealed, Taft and his fellow conservatives deemed Roosevelt a dangerous radical. Once in power for a third term, they said, Roosevelt would be a perpetual chief executive. Roosevelt had become the most dangerous man in American history, said Taft, "because of his hold upon the less intelligent voters and the discontented." The social justice that Roosevelt sought involved, in Taft's opinion, "a forced division of property, and that means socialism."

Taft dominated the Republican Party machinery in many states, but a few state primaries gave the voters a chance to express themselves. The president and his former friend took to the hustings, and across the country in the spring of 1912 the campaign rhetoric escalated. Roosevelt described Taft as a "puzzlewit," while the president labeled Roosevelt a "honeyfugler." Driven to distraction under Roosevelt's attacks, Taft said in Massachusetts, "I was a man of straw; but I have been a man of straw long enough; every man who has blood in his body and who has been misrepresented as I have is forced to fight." A delighted Roosevelt supporter commented that "Taft certainly made a great mistake when he began to ‘fight back.' He has too big a paunch to have much of a punch, while a free-for-all, slap-bang, kick-him-in-the-belly, is just nuts for the chief."

Roosevelt won all the Republican primaries against Taft except in Massachusetts. Taft dominated the caucuses that sent delegates to the state conventions. When the voting was done, neither man had the 540 delegates needed to win. Roosevelt had 411, Taft had 367 and minor candidates had 46, leaving 254 up for grabs. The Republican National Committee, dominated by the Taft forces, awarded 235 delegates to the president and 19 to Roosevelt, thereby ensuring Taft's renomination. Roosevelt believed himself entitled to 72 delegates from Arizona, California, Texas and Washington that had been given to Taft. Firm in his conviction that the nomination was being stolen from him, Roosevelt decided to break the precedent that kept the candidates away from the national convention and lead his forces to Chicago in person. The night before the proceedings Roosevelt told cheering supporters that there was "a great moral issue" at stake and he should have "sixty to eighty lawfully elected delegates" added to his total. Otherwise, he said, the contested delegates should not vote. Roosevelt ended his speech declaring: "Fearless of the future; unheeding of our individual fates; with unflinching hearts and undimmed eyes; we stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord!"

The convention was not Armageddon, but to observers it seemed a close second. Shouts of "liar" and cries of "steamroller" punctuated the proceedings. One pro-Taft observer said that "a tension pervaded the Coliseum breathing the general feeling that a parting of the ways was imminent." William Allen White, the famous Kansas editor, looked down from the press tables "into the human caldron that was boiling all around me."

On the first day, the Roosevelt forces lost a test vote on the temporary chairman. Taft's man, Elihu Root, prevailed. Roosevelt's supporters tried to have 72 of their delegates substituted for Taft partisans on the list of those officially allowed to take part in the convention. When that initiative failed, Roosevelt knew that he could not win, and had earlier rejected the idea of a compromise third candidate. "I'll name the compromise candidate. He'll be me. I'll name the compromise platform. It will be our platform." With that, he bolted from the party and instructed his delegates not to take part in the voting; Taft easily won on the first ballot. Roosevelt, meanwhile, said he was going "to nominate for the presidency a Progressive on a Progressive platform."

In August, Roosevelt did just that, running as the candidate of the Progressive Party. Both he and Taft lost to the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson, that November. Yet, for Republicans who supported Taft, the electoral defeat was worth the ideological victory. As a Republican observed during the campaign: "We can't elect Taft & we must do anything to elect Wilson so as to defeat Roosevelt."

That outcome would resonate for decades. In its week of controversy and recrimination in Chicago, the Republican Party became the party of smaller government and less regulation—and it held to these convictions through the New Deal of the 1930s and beyond.

Lewis L. Gould is the author of Four Hats in the Ring: The 1912 Election and the Birth of Modern American Politics.