The Road to Repatriation

The National Museum of the American Indian works with Native Tribes to bring sacred artifacts home again

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/repatriation_631.jpg)

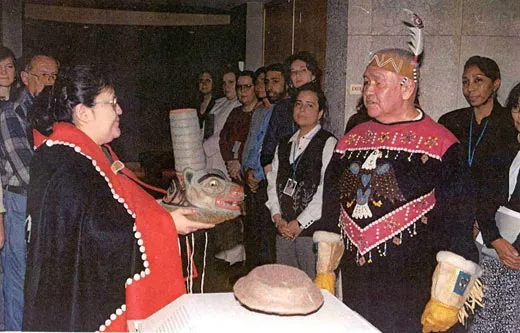

In August 2007, 38 sacred Apache objects traveled from the National Museum of the American Indian’s collection in Maryland to Arizona. The shipping crates featured breathing holes for the masks and revered artifacts inside, which Apaches believe are alive. Before sending them off, a medicine man blessed them with yellow pollen, a holy element that fosters connection with the creator.

After a ceremony at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Apache elders returned the objects to sacred mountains and sites in the Southwest where they believe the spirits reside.

This transfer was one of thousands that have taken place since a series of federal laws in 1989 and 1990 compelled museums to work with Native American tribes across the country in repatriating human remains and sacred objects.

For the Apache, the return of these objects from museum storage to their native soil restores a balance that was thrown off more than a century ago when collectors and archaeologists started stockpiling Indian artifacts.

“The elders told us that they need to come home out of respect,” says Vincent Randall, a Yavapai-Apache who works on repatriation issues. “Otherwise the consequences of fooling around with these things are alcoholism, suicide, domestic violence and all of society’s woes.”

Masks and headdresses are the physical embodiment of spirits for the Apache, so bringing them home is crucial for Native Tribes.

“Once they are created through the instruction of the almighty and are blessed, they become a living entity,” Randall says. “They still have that power. That’s why it’s very potent. We don’t fool around with them.”

Most museum and private collections date back to the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries when the U.S. government moved Native Americans onto reservations. At the time, many scientists wanted to document a culture they believed was vanishing. As both scientists and looters amassed artifacts and human remains in a frenzy of collecting, Native American leaders believe they lost part of their culture.

But far from being the last remnants of an extinct people, some of these artifacts are still integral components of living cultures. Having bones and sacred objects in storage in museums is an affront to Native beliefs.

“Museums and other people think of this as science, something that is not real. They think of them as objects and images that are nothing but artwork,” says Ramon Riley, a White Mountain Apache leader who works on repatriation. “It causes pain to tribal members and our leaders. That is something that only we understand.”

For decades, Native American groups requested the return of these objects and human remains. Though there were occasional repatriations, the protests either fell on deaf ears or tribes lacked the financial and legal support necessary to complete the process.

After lobbying from Native groups, Congress passed the National Museum of the American Indian Act in 1989, which covers the Smithsonian’s collections. It was followed by the 1990 passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which covers all museums and agencies that receive federal funds.

The laws require facilities to offer inventories of all their Native American artifacts to federally recognized tribes in the United States. Human remains, along with and funerary and sacred objects that can be linked to a specific tribe must be repatriated upon request. Grants are available to pay for the travel and research necessary for repatriation. As of 2006, about the remains of about 32,000 individuals had been repatriated under NAGPRA, along with nearly 800,000 objects.

The National Museum of the American Indian has a special field office to take care of repatriation. They have returned about 2,700 artifacts to communities across the Western Hemisphere, from Alaska to Chile. The Smithsonian Institution pays for visits to collections at the repatriation office near Washington, D.C., after which Native leaders can file a formal request. Researchers go through all available resources and may consult with Native experts to determine if the tribe has a relationship with the requested material. If approved, the museum then makes arrangements for returning the objects.

While most museums are extremely accommodating, tribal leaders say contentious issues sometimes arise about which objects are covered by the laws. They say tribal elders know better what should be returned to a tribe than reports by archaeologists and anthropologists.

“The elders have a strong spiritual foundation,” says Randall of the Yavapai-Apache tribe. “The museums use the written word as their bible and we use the real living authorities, which are the elders.”

A recent dispute erupted when the Saginaw Chippewa tribe requested the remains of about 400 individuals in the University of Michigan’s collection. “In our teachings and spirituality, our life journey is not complete until our bones are fully given back to the earth from which we were formed,” says Shannon Martin, director of the tribe’s Ziibiwing cultural center. “For them to be unearthed, disturbed and in boxes on shelves goes against all of our beliefs.”

But the remains, which are between 800 and 1,400 years old, are not affiliated with any particular tribe and are legally required to stay in the university’s collection.

“The Saginaw Chippewa are relatively latecomers into the region, so there is no way they actually have any relationship to the remains,” says John O’Shea, a University of Michigan anthropology professor. He says the large population represented in the remains has “tremendous research value.” Current regulations do not allow the university to give them to the Saginaw Chippewa in order to “preclude any irreversible change in the state of the remains,” O’Shea says. “Lots of different tribes have a potential interest in the remains.”

But the tribe says they have the support of the alliance of all the federally recognized tribes in Michigan, which would prevent any conflict between tribes. Martin says other institutions have given them similar unaffiliated remains, which the tribe buried in an ancestral graveyard.

“In their eyes, history starts when the Europeans laid eyes on us,” Martin says. “They don’t recognize that we had strong alliances, migration and trade before European contact.”

Despite occasional clashes between federal regulations, museums and tribal beliefs, repatriation laws have helped give Native Americans back many of their treasured objects. Riley, the White Mountain Apache, recalls how less than a century ago Apache territory was part of a military base and Native Americans were dismissed as savages and struggled for the right to vote. Repatriation from museum collections was unlikely.

“We were heard but never really understood. Just like the broken treaties,” he says. “Finally the passage of NAGPRA is helping us repatriate our ancestors.”