Befriending Luna the Killer Whale

How a popular Smithsonian story about a stranded orca led to a new documentary about humanity’s link to wild animals

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/gl-luna-631.jpg)

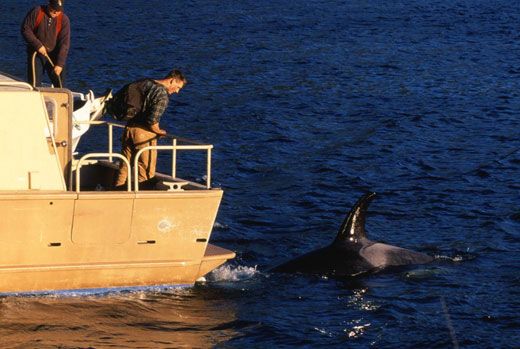

Michael Parfit's story "Whale of a Tale" (Smithsonian, November 2004) documented a phenomenon that was so rare and so touching it was publicized worldwide: a baby killer whale separated from its pod along the Pacific Coast befriended the people of remote Nootka Sound on the western shore of Canada's Vancouver Island. They called him Luna.

The article ended with the attempt by the Canadian government to capture Luna and reunite him with his pod—an effort dramatically blocked by members of a Native American tribe, who rowed out in traditional canoes to intercept the government boat.

For the next two years, Parfit and Suzanne Chisholm, a documentary moviemaker, continued to follow Luna and report on his astonishing impact on the community. The orca would live in the area for more than four years.

Chisholm's and Parfit's film, Saving Luna: The True Story of a Lone Orca, is showing at film festivals and other events around the world. See SavingLuna.com for venues and to learn more. This past March I spoke with Parfit and Chisholm, who are married, when they were in Washington D.C. to screen the movie at the Environmental Film Festival. (Yes, we know: orcas are not really whales but dolphins.)

What makes Luna unique?

Suzanne Chisholm: Killer whales are in some ways even more social than humans. They spend their entire lives together in family groups. At first, scientists didn't believe reports that there was this baby killer whale all by himself. Because they had never recorded an event like that before, they were very skeptical that he would survive. He was just about two years old, barely weaned.

Not only did he survive, but he started to thrive. One of the ways in which he compensated for the loss of his family was interaction with people. They became his family. It's not to say that we humans are a good replacement for whales. But he would do a lot of the things with boats or people that he would have done with other whales.

They are very tactile animals. In the wild they are always touching and bumping and swimming very close to each other. He would do that to boats, come up and rub alongside of them. He would come up to people and vocalize. He would roll over on his side and look people in the eye.

This was just for companionship?

Chisholm: When you think about our relationships with wild animals, whether it is a bear, a deer or even hummingbirds, they come to us for food. Cetaceans, the whales and the dolphins, are really the only animals that come to us strictly for companionship.

He was starting to interact a lot with boats, and people were worried for his safety. People figured he was quite lonely and would be best off with his family. He wouldn't leave Nootka Sound, so even though conceivably his family swam on the western coast of Vancouver Island, he was isolated. They communicate with underwater calls and whistles. If he had heard his family, he might have gone back to them.

How long did the process take from when you first got there to the end of the story?

Chisholm: We went up there in 2004 just as the government was trying to capture him. You know from the Smithsonian article that the First Nations interfered with the capture. We lived up there for another two and a half years, pretty much full time for the last year. We ended up getting quite involved in trying to change the outcome of the story, trying to help save Luna.

Was it inevitable that you would become part of the story?

Chisholm: I guess in hindsight you could say so. You have an innocent and intelligent creature who needed help from humans. There was a huge amount of conflict over what was the right thing to do for him. After this big event in which the natives came out and prevented the capture from happening, you can look at it as a victory for Luna. It was quite possible that he would have gone into an aquarium had the capture gone through.

The government didn't have a very clear plan. If he got back down to the area where his pod was and still played with boats, the government wasn't going to give him very much time before they said "Okay, that's it, you're going to be shipped off to an aquarium." Of course, Luna was worth huge amounts of money to these aquariums. He was obviously a very intelligent, healthy killer whale.

That's one of the reasons the Native American tribes opposed it.

Chisholm: The media coverage put a very strong emphasis on the First Nations' cultural connection to the whale. When their chief passed away he said he was coming back as a killer whale. The same week that he died, Luna showed up in Nootka Sound. The killer whale happens to be a very sacred creature in their culture. A lot of them believed the whale embodied the spirit of their chief.

From our point of view he was an animal who needed help. It felt strange to be there covering this story and not trying to help him. We weren't what you call activists, but we really wanted to get out the information that here was a physically healthy, obviously intelligent animal in difficult circumstances. Captivity is a horrible life for these animals. They swim 100 miles a day. For them to be in a small, confined area is not a good life for these animals.

What were you doing to increase awareness?

Chisholm: We spent a lot of time writing for the Web. We also spent a lot of time and our own money going out on a boat and talking to people on the water. There were a lot of people frustrated with the situation. Luna was very persistent in trying to get attention. He would sometimes push boats around. People were threatening to kill him.

He wasn't malicious. He was just playful. Sometimes he would break things. He damaged a septic system at a marina. He would damage rudders on sailboats. He would also break off little transducers and depth sounders on the bottom of boats. He started playing with float planes, which have very fine control rudders and stuff. It was quite scary. There is no question that his presence was a problem for humans. That's something that we humans have to figure out. As we expand our territories, it's inevitable that there are going to be conflicts with wild animals. We should have done more to accommodate his presence.

Both of you developed a strong relationship with the whale.

Chisholm: We had never thought that it would be possible to have that kind of relationship with a wild animal. When Luna did come to us humans, he was asking for something, and I know it wasn't food. To have a wild animal come to you for social contact is really quite an amazing thing. He would flap his flippers, or turn over and look you in the eye. There was so much about him that we didn't know. Clearly he was trying to communicate. He would mimic sounds. If somebody would whistle he would whistle back in the same pitch. He also imitated sounds of chainsaws.

One of the things that struck us was he was extremely gentle. Never once were we scared for our own safety. There is no history of killer whales ever attacking humans in the wild.

Did he get to be full grown?

Chisholm: No, he was about 18 feet long. The males grow to be about 30 feet long. The big concern was that there would be an accident. The bigger he got, the stronger he would become. They are big animals with very big teeth, and he looks a little bit scary if you don't know any better.

How did he die?

Chisholm: He was six when he was killed . He was swimming behind a large tugboat. These tugs are massive, they've got propellers several meters long. The tug captain put the vessel into reverse and Luna was sucked into the propeller.

It sounds as if that was also kind of inevitable.

Chisholm: Well, I don't think so. The government was really not willing to try anything. After the failed capture event they threw up their hands and said "We don't know what to do here."

The program we were trying to get in place was one where he had a safe boat to come to for interaction. The idea was he needed social contact with somebody. If you have a safe boat, with trained professionals, designed by scientists and people who knew Luna's behavior, then he would get his interaction in a safe and consistent manner. We know that he needs his contact. If you could give him interaction in a safe way, he wouldn't be a danger.

The second part of our idea would be to lead him outside of Nootka Sound. If you could lead him out of Nootka Sound on a repeated basis it would expand his territory and give him the option that in the event his pod did pass by that he could make the decision whether to go with them or not. Hopefully he would have.

There was reluctance on the part of a lot of people to give him interaction because they thought it might spoil his chances of becoming a wild whale again. We argued that you've got to do something, because he was on a collision course.

Did you have qualms about becoming involved?

Chisholm: We agonized huge amounts over it. As journalists and filmmakers we hadn't really done that. It seemed like the most natural thing to do, because we thought that we were in a position to help him. It's one of those things we wouldn't have predicted when we got this assignment from Smithsonian to do this article. Who would have ever known that we would have spent so many years of our lives covering this? It's coming up on four years now.

What response has the film gotten from people?

Chisholm: In December we went to a film festival in China. It was very interesting because you don't assume that every culture has a fascination for whales and dolphins. But when we showed this film in China we had an incredible response. People were crying. The affection and respect that we had for Luna is a universal story.

Michael Parfit: People all over have responded to it. We tried to make it a universal story and not focus on the politics.

What makes him such a great story?

Parfit: To have a large, dynamic wild animal come up to you and need your attention, your affection, is just stunning. These sorts of things happen in fables. We have all these stories that we've heard as children about human beings making contact with one animal or another, but it really doesn't happen. Wild animals come to us when they are hungry or starving or they have dropped out of their nest and they need food. Sometimes we buy their friendship with food. This little whale didn't need that. He didn't need anything except what we call friendship. It breaks through all of these preconceived walls we have between ourselves and wild animals.

We think of these animals as not having anything related to our emotions. Here's an animal that needs a social life as much as life itself. He wound up dying because he needed this contact. All of a sudden we can recognize that in ourselves. We know we need one another. Now we are recognizing this need in this whale. He doesn't look like us. He doesn't come from the same environment. He's practically from another planet.

What are the broader lessons?

Parfit: Needing one another in order to survive is not unique to humans. Because Luna experienced something that is similar to what we experience, it kind of shuffled our perception of the world. We can't take ourselves out of the picture. With Luna, we had to figure out how to relate to him in a way that would not hurt him. With him we did not learn how to do that. He wound up being killed just because he was being friendly. It's appalling to think that an animal would have to die because he wants to be friends with us. That is kind of what our relation to the whole planet is.

Chisholm: We have to open up our minds and look at the signs and seek more understanding of these creatures, whether it's killer whales or a tree frog or changing climate. We all need to do better.