Yeasts of the Southern Wild

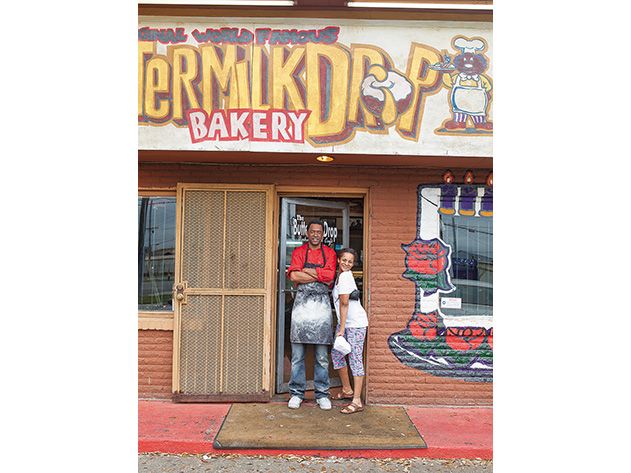

Maker of the “world famous buttermilk drop,” New Orleans actor Dwight Henry is expanding his baking empire

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/New-Orleans-bakery-Dwight-Henry-631.jpg)

As I entered the one-story, brick-and-galvanized, gaily illustrated Buttermilk Drop Bakery and Café in New Orleans, to the smell of cinnamon and sugar glaze, I heard this exclamation from deep inside: “The devil’s music shall not be heard in the house of the Lord!” And again. A little differently. And again! A little differently. And no music at all. What kind of bakery, I wondered, is this?

Well, that was just the Buttermilk Drop’s proprietor, Dwight Henry. He was rehearsing for his role as Marvin Gaye’s father in Sexual Healing, a forthcoming biopic about the great Motown singer. Three years ago, an arty young film crew, who had come to know Henry through his pastry, talked him into taking the lead male role in his first movie, Beasts of the Southern Wild, which won a best-picture Oscar nomination.

Now Henry has been to Sundance, Cannes, the White House and on TV with Oprah Winfrey. With Richie Notar, a New York restaurateur who has partnered with Robert De Niro, Henry will soon be opening another outlet for his cooking, in Harlem. With Wendell Pierce, star of HBO’s “The Wire” and “Treme,” he has at least one more New Orleans bakery in the works. With Brad Pitt, he’ll be appearing this fall in his second feature film, Twelve Years a Slave. “I died in those first two movies,” he observes. “In this next one, I kill somebody.” Legions of veteran actors would kill to have one death scene, en masse if necessary. Henry the baker takes the movies as they come.

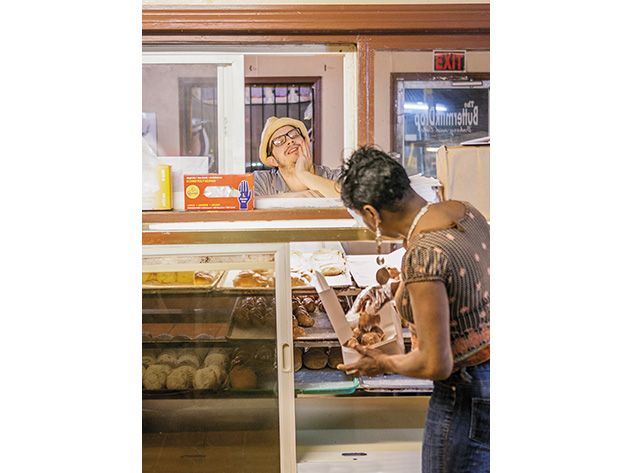

Gaudy images outside and inside his establishment (on the ceiling, even, and the roof!) depict a beaming, roly-poly figure with a face a bit like a Super Mario Brother’s on a head very much like a buttermilk drop—which is a round, brown, glazed, cakey confection slightly smaller, but heavier, than a racquetball. Otherwise, the place is not big on ambience. The two tables are usually unoccupied, because the business is primarily takeout. There are separate windows inside for ordering and paying, but customers pretty much use the former window for both, so there’s a lot of milling around. Still, turnover is brisk. Along with her order, a lady wearing fleur-de-lis pajama pants and a New Orleans Saints hoodie offers an unsolicited endorsement:

“Charles got the hypoglycemia, and wakes up in the night, got to have a cinnamon bun, and he don’t want a cinnamon bun you get at the store comes in a bag, he’s got to have a Henry’s cinnamon bun.”

Another patron, in a T-shirt that says “Ride It Like You Stole It,” looks up at the baker painted on the ceiling and announces, to no one in particular, “Still and all, you ain’t no more than me.”

When you look at Dwight Henry himself—medium-sized, trim and ruggedly good-looking, his demeanor an affable glaze over a tightly wound core—you see a real baker. “When I was a junior in high school, in the Ninth Ward, everybody worked at the Reising Sunrise bakery there,” he says. “My first job, I was just picking up, putting away and cleaning out. But I’d look over at the boys in the bread department, and I’d think to myself, ‘Someday I’m going to be in bread.’”

A bland ambition, you might think, for a spirited New Orleanian youth, but Dwight Henry is heir to a great tradition. When outsiders think of New Orleans cuisine, baked goods probably don’t spring to mind, but the 1885 book Creole Cookery includes 128 recipes for breads and 165 for cakes, compared with 88 for soups, fish and shellfish combined. New Orleanians know their bakeries—past (ah, the one at the old Woolworth’s on Canal!) and present. Leidenheimer’s, currently the largest, retains the artisanal specialties of several competitors it has bought up over the years. Leidenheimer delivery trucks are highly visible around town, emblazoned as they are with cartoonery by local artist Bunny Matthews. (Vic and Nat’ly, two well-known characters identified with the Yat dialect, biting into either end of an overflowing shrimp po’ boy, with the caption, “Sink ya teeth into a piece of New Orleans cultcha!”)

The French bread, so-called, of New Orleans is unique. Its loaf is long and with rounded tips. Its texture combines airy interior and shattery crust. This bread must be substantial enough to hold the contents of a po’ boy—anything from fried oysters to chicken livers to eggplant parmigiana to roast beef “debris”—yet soft enough not to cut into the roof of the biter’s mouth, and absorbent enough to retain a significant portion, though never by any means all, of the juices involved. When stale, that bread is right for the distinctive local version of French toast, which local menus and cookbooks call pain perdu, as in the old country, or even “lost bread,” in literal translation.

Then there’s king cake, served at Mardi Gras and other holidays (if you get the piece with the little plastic baby inside, you have to provide the king cake next time), and the beignets of Café Du Monde, and Doberge Cake, and Bananas Foster bread pudding, and crunchy “stage planks” (sometimes called gingerbread tiles), and symbolic St. Joseph’s Day loaves, and the special big round bun of a muffuletta sandwich. Last summer, fire destroyed the Hubig’s Pies factory on Dauphine Street, the only place in the world turning out Hubig’s New Orleans-style pies. So many hungering local pie-lovers have launched campaigns in support of Hubig’s rebuilding that the company’s website declares, “We appreciate the attempts to help, but ask those using the Hubig’s name, brand or likeness to cease.”

Buttermilk drops were a specialty of McKenzie’s, a late, sorely missed chain of bakeries. Dwight Henry worked there, and also at Tastee Donuts, Dorignac’s Food Center, Alois J. Binder, Southern Hospitality Catering, Southshore Donuts and Whole Foods Market. Along the way he acquired influences—not to say recipes. When after 15 years or so of wide-ranging apprenticeship he undertook to start his own line of goods, “I just tasted, and tried various things, and tasted.” As for the buttermilk drop, “there’s some buttermilk in it. Some...other things. Ancient Chinese secret.” A local online reviewer of his goods noted the obvious McKenzie’s touch in both buttermilk drops and glazed doughnuts. The reviewer deemed the raisin and cinnamon squares to be “a straight-up homage” to the old Woolworth’s. Along with other pastry buffs, he engaged in “guessing games about the origins of Henry’s recipes for figure-eight braids and crusty apple fritters....The king cake, however, is pure Henry’s: delicious, exuberantly decorated, an excellent value, redolent of old New Orleans traditions.”

Learning the baking is one thing. Lining up backing was another. “After McKenzie closed down, 60 stores in one day, it left a huge void in the industry,” Henry says. “But when I tried to get financing, every friend, every family member, every bank, every finance company, they all turned me down. No one believed in me but me.” He kept applying. “People made fun of me: ‘Where you going with the briefcase, man?’ I worked two jobs, one paycheck for my family, one to put away for my own place. I bought used equipment, a piece at a time. Stored it in my grandmother’s garage. Took me three years to open up. And the rest”—beginning at the baking, mark you, not the movies—“is history.”

That first Buttermilk Drop was in an emerging neighborhood, the Marigny/Bywater, which attracted artists, including a collective out of the Northeast called Court 13. They were in New Orleans planning Beasts of the Southern Wild when Katrina hit in 2005. After the storm, there were hardly any eating places open in the neighborhood, but soon Henry had single-handedly gutted and restored the Buttermilk Drop, so, says Benh Zeitlin, the movie’s director, “We ate breakfast and lunch there nearly every day.” The 13ers valued Henry for his pastries “and also,” Zeitlin says, pausing for an unspoken mmm, “his smothered pork chops.”

They had found their female lead—Hushpuppy, the character is called—in the irresistible moppet Quvenzhané Wallis, whose staunch lower lip, wind-swept Afro and surreal unflappability made up for her complete lack of acting experience. But none of the untrained locals they tested were tough enough to play her father, Wink. “That was the one role that required an experienced actor, we thought,” Zeitlin says. But the more they got to know Henry, the more he and the character began to overlap. “We saw him as part of the template for what Wink could be like,” Zeitlin says. “So we said, ‘Let’s bring in Dwight to see if he can act at all.’” They taped him just talking about his life. Acting, schmacting; the character had already begun to become “very much a collaboration” between the filmmakers and the baker. But when they came to urge him to take the part, the Buttermilk Drop was gone.

Without informing the filmmakers, Henry had moved to his current location, where there is more parking. The corner of St. Bernard and Dorgenois is in a down-market neighborhood only partly recovered from the devastation of 2005. A few blocks away a sign proclaims “Tony’s Historical Parakeet Restaurant Bar and Lounge, 1966 Hope St., Chocolate City LA, ‘We Survived Katrina, Rita, Gustav and Ike—We’re Back.’” But nearby, Vaucresson’s Sausage Company, “A New Orleans Tradition Since 1899,” is still boarded up from Katrina, so all you can see of the big painting of the late Robert “Sonny” Levinsky Vaucresson, son and successor of the founder, is the top of his big white hat. When at length the filmmakers tracked Henry down, he was loath to enter into any artistic enterprise that might cause the Buttermilk Drop man’s toque to be so obscured. Henry has five kids. “I can see me being in the bakery business for 30 years, and my children, and grandchildren, holding it down for 100 years. When the movie people walked in, wanted me to be in the movie, that I’m going to be a star, I said, ‘No No No No, I’m not going to sacrifice my children’s future for a possible movie career.’”

At length he agreed to do Beasts of the Southern Wild—but only on the condition that his rehearsing would be during baker’s hours. So Zeitlin would show up after midnight, and as Henry, in his apron, rolled and cut dough and put things into the oven for the next morning, they would run lines, sometimes reworking them so they were the way Henry would say them. “And he wanted to know me as a person,” Henry says. “We’d talk about every little thing.” Wink has to teach his motherless daughter, Hushpuppy, to survive, independently, on their tempest-tossed bayou because Wink is dying. In the bakery at night, Henry told Zeitlin about raising his own daughter, and about finding his own father dead. In Wink’s death scene, says Henry, “as I was lying there, Benh is right behind me, off-camera, saying, ‘Dwight, remember the time we talked about your father, that emotion, when you found your father on the sofa.’”

In that scene both Wink and Hushpuppy shed credible tears, but before that, Wink drunkenly constrains Hushpuppy to rip a crab apart with her hands and shows her how to catch a catfish barehanded. After she resentfully burns down the hovel in which she lives, he slaps her sprawling. “I’m your daddy,” he says, “and it’s my job to take care of you, OK?”

This would seem an extreme form of tough love, but Hushpuppy handles it. You know how you’d like to see Shrek go one-on-one with King Kong, or Russell Crowe with Robert Mitchum? In those cases I think the old guys win, but in a bout of spunky adorability, Quvenzhané Wallis would mop up the floor with Shirley Temple. Many an actor whose first film role required him to belt that luminous child (did I mention that she has signed to play the title role in an African-American movie version of Annie?) would have had a hard time finding public absolution, much less a second role. But Henry (not to mention the dazzling visual aspects of the film) carries enough conviction to hold judgments of correctness at bay. He’s not like Wink, he says. “I’m a well-dressed person, and Wink doesn’t dress too well.” (Usually in dirty overalls or a hospital gown.) “Wink drinks, I don’t drink. Wink is loud. I’m real calm. But I’m loving like Wink.” (His 10-year-old daughter, he has said, “is my only little girl, and I can’t even fix my mouth to tell her no for anything.”)

Sudden fame can run somebody ragged, but Henry, at 47, seems to be taking it in stride. “I wanted him to come see me, see how I do things, drink the Kool-Aid,” says Notar, his New York partner. “He said, ‘Rich, I’d love to, but the first lady has invited me to the White House to meet the kids, make some beignets.’ I said, ‘I’ve been given a lot of excuses, but how can I compete with that?’ True to life, this guy left the White House early, got on a train and came here” to catch the opening-night party for Notar’s swank restaurant, Harlow. The space is said to have been built originally by William Randolph Hearst for Marion Davies to entertain in. Prominent in its entryway is an Andy Warhol painting of a red stiletto-heel shoe. Among the guests mentioned in the social notes the next day were Martha Stewart, Naomi Campbell, various men known in Gotham social notes as “corporate whales” and “the improbably renowned baker, Dwight Henry.”

The average Harlow check, according to Notar, is $95 to $110. At the Buttermilk Drop, you can get a hearty breakfast, rounded off by a glazed chocolate jelly doughnut that will stay with you the rest of the day, for $5.19. The menu and prices are as yet undetermined for Mr. Henry’s, the eatery Notar and Henry plan to establish. It will be next door to the café and club Notar plans to open this August on the original site of the legendary jazz venue the Lenox Lounge. Notar doesn’t want it to lack a common touch. “Whenever I do a restaurant—Hong Kong, Vegas, Milan—first thing I think about is the local people. Because they’re going to be with you day to day. People I call fillers. Because you know the fabulous crowd is very fickle. Your food tastes better when you’re seated next to Bruce Willis—I don’t agree with it, but this is the power of celebrity. But at the end of the day, on a Monday, February, 6 o’clock, you need those people, you don’t want them to know they’ve been boxed out.”

If Mr. Henry’s gets well-branded, Notar says, it could go global. Skeptics may well wonder whether Henry himself, who so recently lived and worked among fillers pretty exclusively, can spread himself that thin. Well, he has shown a capacity to contract, as well as to expand. The Buttermilk Drop man on his ceiling is juggling a dozen different dishes. A sign outside claims, “We specialize in Stuffed Bell Peppers, Macaroni and Cheese, Gumbo Potato Salad, Smothered Chops, Chicken and Turkey, Red/White Beans and Rice and Much More.” Since other vistas have opened up for Henry, the Drop has retreated to high-profit-margin items: pastries and, in the morning, scrambled eggs and grits and bacon or sausage or, sometimes, liver or pork chops.

One reason Henry holds his own so well in Beasts, no doubt, is that he represents another New Orleans tradition. He says he survived his first hurricane as an infant—in 1965 he rode Betsy out on a roof. As Katrina approached 40 years later, he refused to evacuate. “I’m always going to be one of the holdouts—some people got to stay back,” he says. “I don’t put my tail between my legs, walk away from my business, let vandals come in and destroy everything I worked so hard for.”

He set up in a friend’s house in the Gentilly area, not far from Lake Pontchartrain. “We were used to the storm coming, the storm going. We never expected the levees to break and the water to stay. If I’d known....” When he and his friend woke up, water was already in the house. And rising. Fast. “I panicked! We got to get away from this lake.” They plunged into neck-high water and walked to a strip mall, “a little island where a hundred families” had gathered. “Stood there a week and a half. Slept up in a place that did taxes. We vandalized—we didn’t vandalize, and I don’t want to use the word ‘break-in.’ We got into some stores. For dry clothes, barbecue grills, meat, plates—got everybody eating. Seniors needed medicine from the drugstore. But if I’d known, I would’ve put my tail between my legs.”

When it comes to not getting carried away, then, Henry has a sense of options. The last time I saw him in his place, he would soon fly off to Luxembourg, to shoot Marvin Gaye. Maybe someday he’ll be remembered globally, for his repertoire of rough-daddy roles. Locally, he’ll still be the man who revived the buttermilk drop. When I shook his hand, it had flour on it.