Evolution World Tour: Wadi Hitan, Egypt

In Egypt’s Western Desert, evidence abounds that before they were the kings of the ocean, whales roamed the earth on four legs

In 1902, a team of geologists guided their camels into a valley in Egypt’s Western Desert—a desolate, dream-like place. Centuries of strong wind had sculpted sandstone rocks into alien shapes, and at night the moonlight was so bright that the sand glowed like gold. There was no water for miles. A nearby hill was known as “Mountain of Hell” because of the infernal summer heat.

Yet in this parched valley lay the bones of whales.

Some of the skeletons were 50 feet long, with vertebrae as thick as campfire logs. They dated back 37 million years, to an era when a shallow, tropical sea covered this area and all of northern Egypt.

And although the geologists didn’t realize it at the time, the prehistoric specimens in the sand would offer clues to one of evolution’s most nagging questions: how whales became whales in the first place. For these long-dead whales had feet.

“We had sometimes joked about walking whales,” says Philip Gingerich, a University of Michigan paleontologist who discovered the dainty little appendages, complete with tiny toes, when working in Wadi Hitan (“The Valley of the Whales”) in 1989. “When we found what we did in Egypt, we thought, ‘That’s not a joke anymore.’”

Scientists had long suspected that whales were terrestrial mammals that had eased into the ocean over millions of years, gradually losing their four legs. Modern whales, after all, have vestigial hind leg bones. But little in the fossil record illustrated the transition—until Gingerich began excavating Wadi Hitan’s hundreds of whale fossils, finding legs and knees.

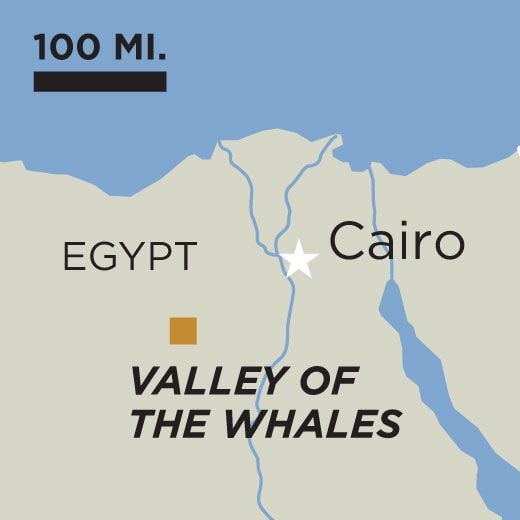

Those skeletons “are the Rosetta stones,” says Nick Pyenson, a curator of fossil marine mammals at the National Museum of Natural History. “It’s the first time we could say we know what the hind limbs of these animals look like. And they’re bizarre.” Older specimens of footed whales have since been identified, but Wadi Hitan’s are unmatched in their numbers and state of preservation. The valley—about a three-hour drive from Cairo—is now a Unesco World Heritage site visited by some 14,000 people each year.

Gingerich speculates that whales’ landlubber ancestors were deer- or pig-like scavengers living near the sea. About 55 million years ago, they started spending more time in the water, first eating dead fish along the shore, and then chasing prey in the shallows, and then wading deeper. As they did, some evolved traits that facilitated hunting in water. Over time—since they no longer had to bear their full body weight at sea—they got bigger, their backbones elongating and their rib cages broadening.

Fossils from India, even older than the ones studied in Egypt, reveal that the whale’s earliest ocean-dwelling ancestors kept their footing, using their legs to climb in and out of the water—most likely for breeding and giving birth on shore. But the more they relied on tails for locomotion, the more their legs shrank. “If you’re going to be using your tail, legs get in the way,” Pyenson says. “Smaller legs reduce drag. You want to become streamlined.” The whales of Wadi Hitan had evolved to the point where they could not return to land. They were school bus-size creatures with feet only a few inches long, useless for walking. Eventually, the whales’ legs would disappear altogether.

Most of the fossils in the valley belong to two types: Basilosaurus was the giant, with an almost eel-like body. The more petite but heavily muscled Dorudon looked more like a modern whale, at least until its mouth opened to reveal a jaw lined with serrated daggers instead of peg-like teeth.

Far from a playground for gentle giants, prehistoric Wadi Hitan was a whale-eat-whale world. That part of Egypt was likely a warm, nutrient-rich elongated gulf not unlike modern Baja California, where gray whales today come to bear young. Gingerich thinks that Dorudon likewise calved in the shallows, because there are unusual numbers of juvenile skeletons at the site. Some of the baby Dorudon have bite marks on their heads, likely inflicted by hungry Basilosauruses. Both whale ancestors would have feasted on other creatures in the area, which was home to sea cows, giant crocodiles, sharks and myriad other fish. Dorudon skeletons are sometimes found with jumbles of fish bones where their stomachs would have been. The Basilosaurus’ teeth are typically broken from extensive use.

Once quite difficult to reach, Wadi Hitan has recently become an ecotourism destination. It is part of Wadi El-Rayan, a larger protected area that also includes a Saharan oasis inhabited by Dorcas gazelles and Fennec foxes. Visitors can hire a driver (preferably with a four-wheel-drive vehicle) in Cairo and travel over recently improved roads to the valley. The site includes an open-air museum with footpaths alongside some of the fossils, which are fully or partially exposed and easy to see. And, provided they remember to bring wood for the fire pit, the most intrepid guests can camp overnight on the ancient seafloor and sleep with the whales.

The skeletons are much as they were when the first geologists found them. In death, Dorudon almost always assumed a circular posture. Basilosaurus tended to come to rest in a more or less straight line. The ocean current perhaps pushed the bodies parallel to the coast. Using the whales’ positions, scientists may one day be able to discern the shape of long-lost shores.