Eleven Times When Americans Have Marched in Protest on Washington

Revisiting some of the country’s most memorable uses of the right to assemble

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cc/f8/ccf8bf59-b776-4fd6-82f2-229ae46033f7/kentstateprotest-wr.jpg)

Even in a republic built by and for the people, national politics can feel disconnected from the concerns of American citizens. And when there are months or years between elections, there’s one method people have turned to again and again to voice their concerns: marches on Washington. The capital has played host to a fleet of family farmers on tractors in 1979, a crowd of 215,000 led by comedians Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert in the 2010 Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear, a brigade of 1,500 puppets championing public media (inspired by presidential candidate Mitt Romney’s comments about Big Bird and funding for public television), and the annual March for Life rally that brings together evangelicals and other groups protesting abortion.

In anticipation of the next big march on Washington, explore ten of the largest marches on Washington. From the Ku Klux Klan to the People’s Anti-War Mobilization, Washington’s history of marches is a testament to the ever-evolving social, cultural and political milieu of America.

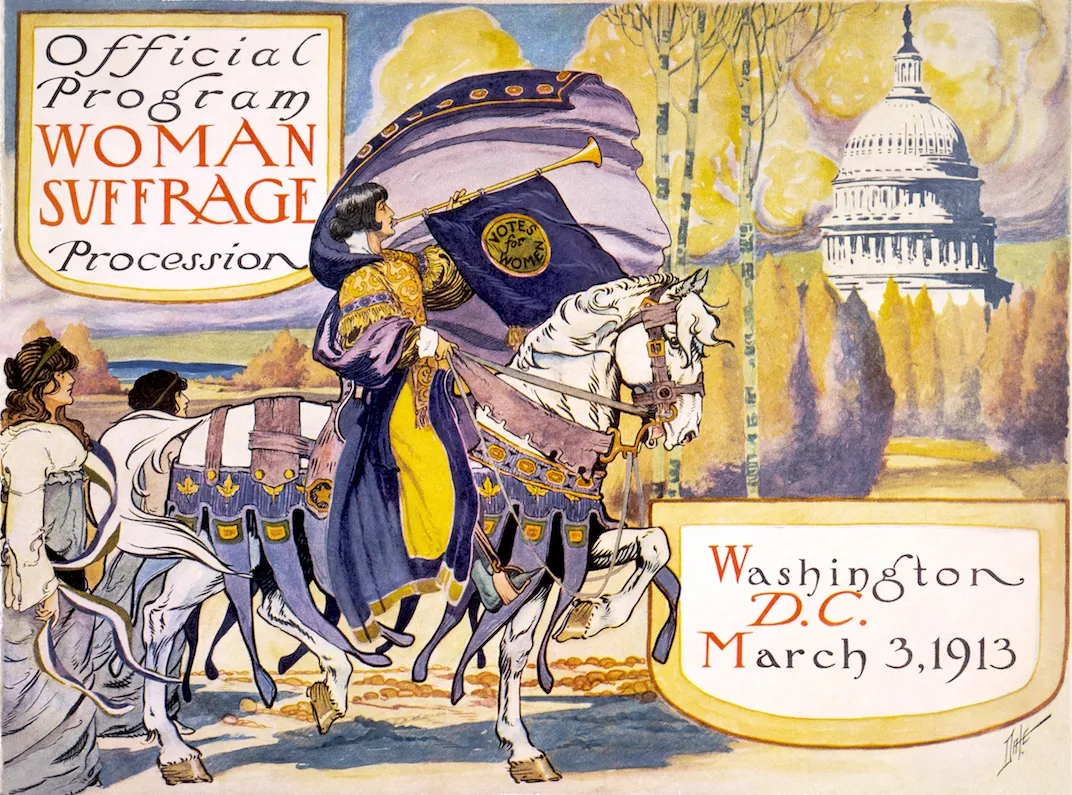

Women’s Suffrage March – March 3, 1913

One day before Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration, 5,000 women paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue to demand the right to vote. It was the first civil rights parade to use the capital as its stage, and it drew plenty of attention—500,000 spectators watched the procession. The march was organized by suffragist Alice Paul and led by labor lawyer Inez Milholland, who rode a white horse named Gray Dawn and was dressed in a blue cape, white boots and a crown. The Washington Post called her “the most beautiful suffragist,” a title to which she responded, “I like it… I wish, however, that I had been given another one which would suggest intellectuality rather than beauty, as that is much more essential.”

Ku Klux Klan March – August 8, 1925

Spurred by hatred of European Catholics, Jewish immigrants and African-Americans and inspired by the silent film Birth of a Nation (in which Klansmen were portrayed as heroes), the Ku Klux Klan had an astounding 3 million members in the 1920s (The U.S. population at the time was just 106.5 million people.) But there were rifts between members from the North and the South, and to bridge that divide—and make their presence known—they gathered in Washington. Between 50,000 and 60,000 Klansmen participated in the event, and wore their ominous cloaks and hats, though masks were forbidden. Despite fears that the march would lead to violence, it was a largely silent, peaceable event—and plenty of newspapers’ editorial sections cheered the Klan on. A Maryland newspaper described its readers as “quivering in excited anticipation of 100,000 ghostly apparitions wafting through the streets of the national capital to stirring strains of the ‘Liberty Stable Blues.’”

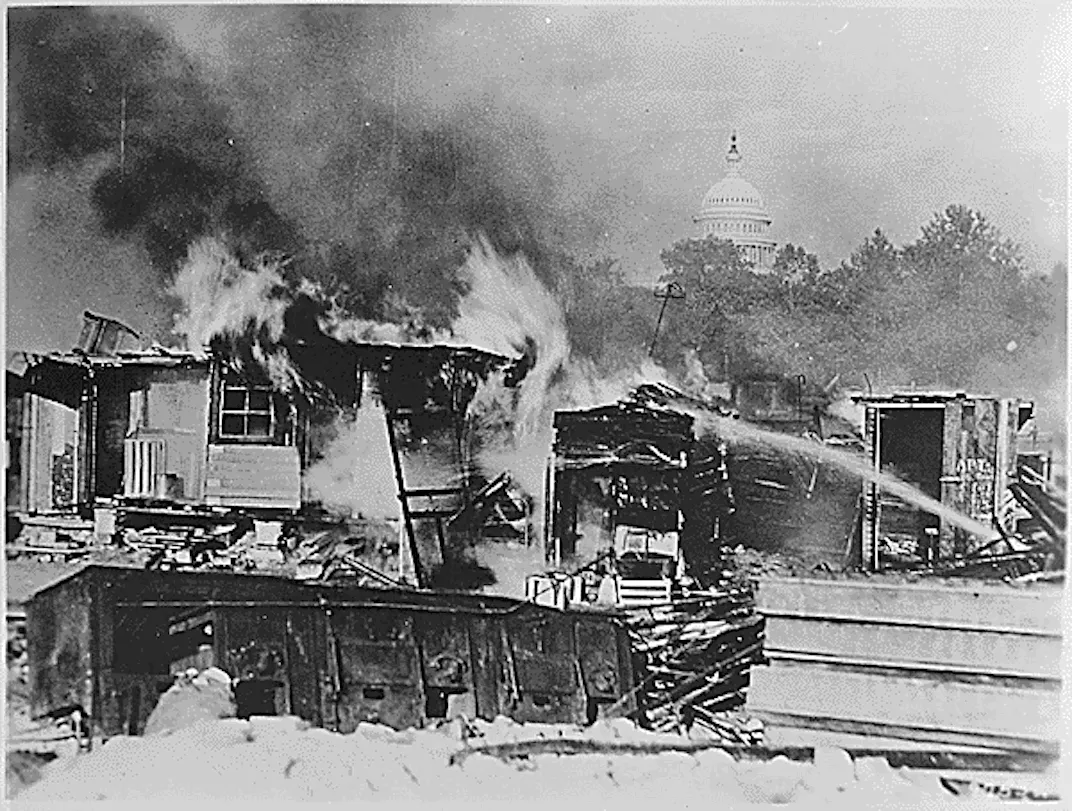

Bonus Army March – June 17, 1932

A few years after the end of World War I, Congress rewarded American veterans with certificates valued at $1,000 that wouldn’t be redeemable for their full amount for more than 20 years. But when the Great Depression led to mass unemployment and hunger, desperate vets hoped to cash in their bonuses ahead of schedule. In the early years of the Depression, a number of marches and demonstrations took place around the country: a Communist-led hunger march on Washington in December of 1931, an army of 12,000 jobless men in Pittsburgh, and a riot at Ford’s River Rouge plant in Michigan that left four dead.

Most famous of all were the “Bonus Expeditionary Forces” led by former cannery worker Walter W. Walters. Walters assembled 20,000 vets, some with their families, to wait until a veterans’ bill was passed in Congress that would allow the vets to collect their bonuses. But when it was defeated in the Senate on June 17, desperation broke through the previously peaceful crowd. Army troops led by Douglas MacArthur, then the Chief of Staff for the U.S. Army, chased the veterans out, employing gas, bayonets and sabers and destroying the makeshift camps in the process. The violence of the response seemed, to many, out of proportion, and contributed to souring public opinion on President Herbert Hoover.

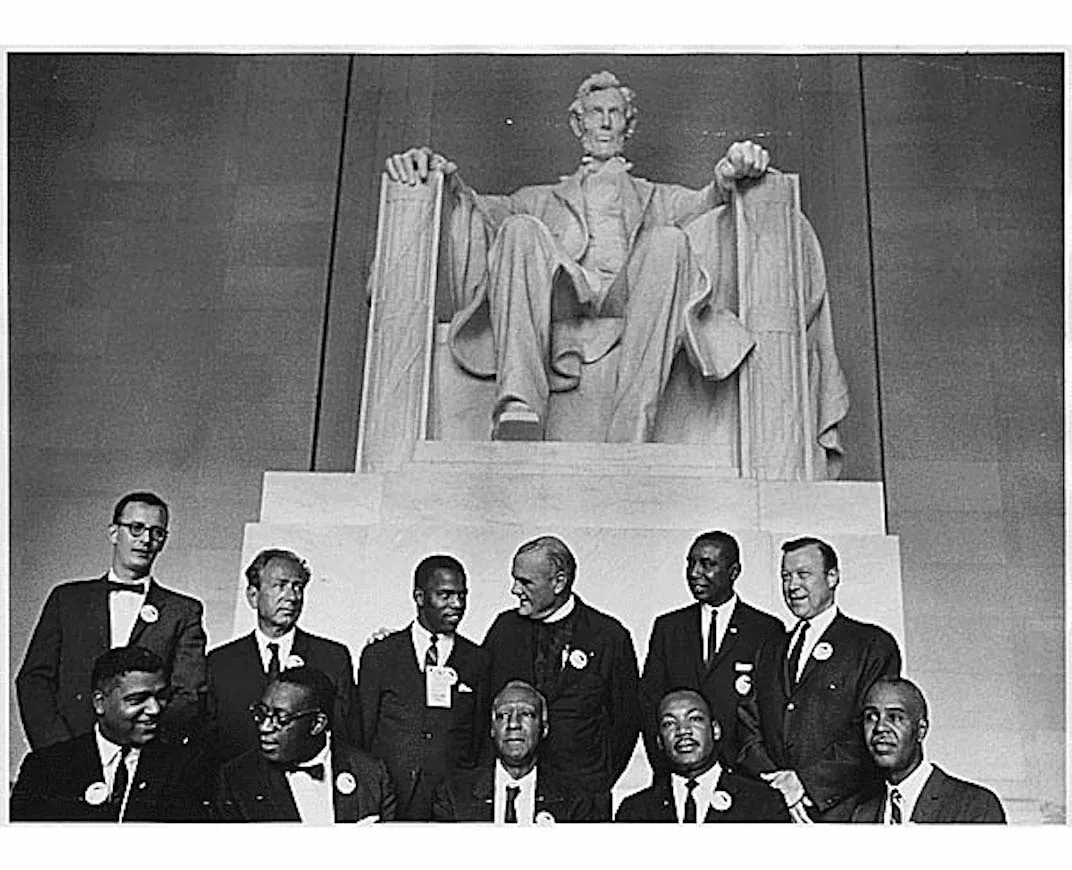

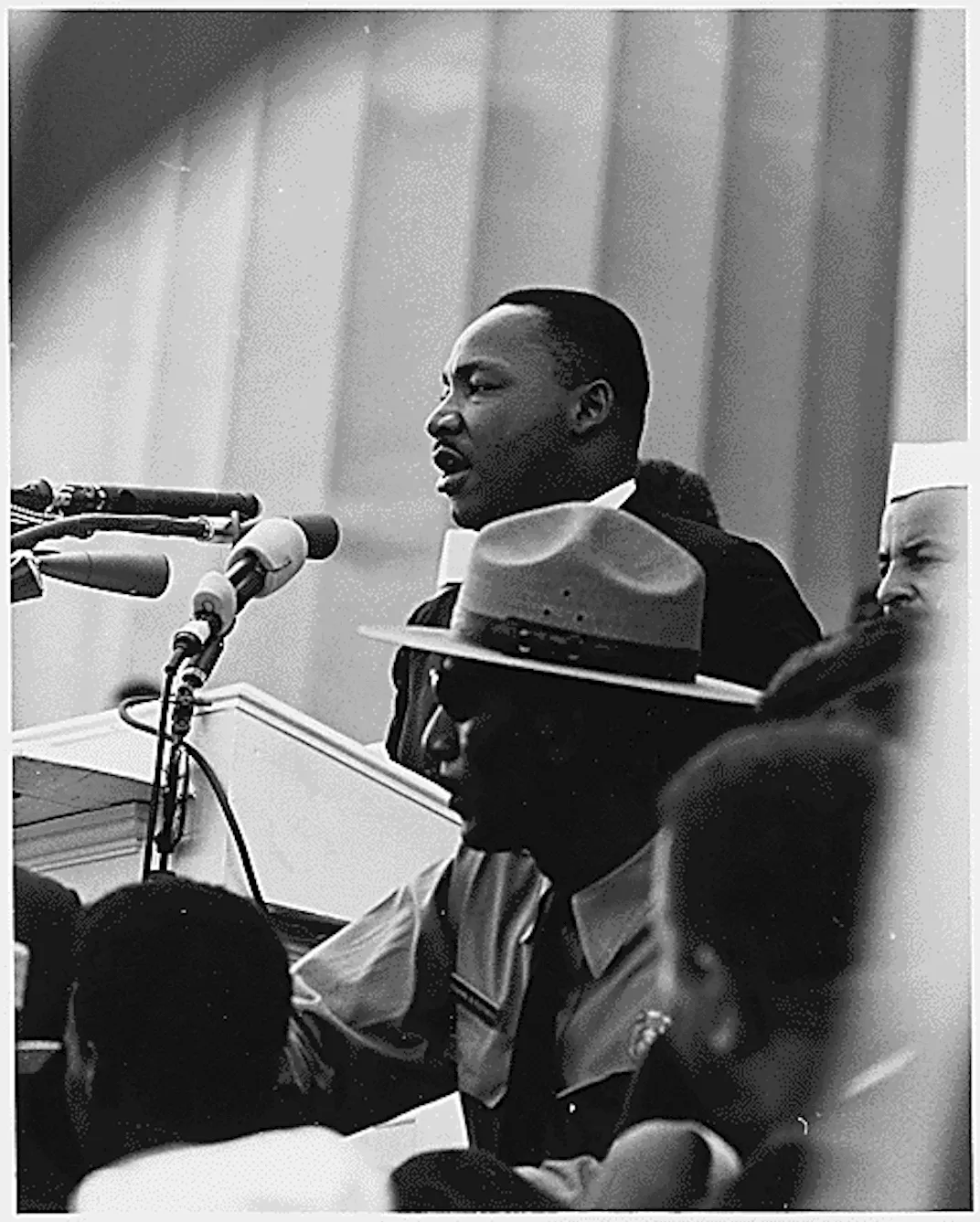

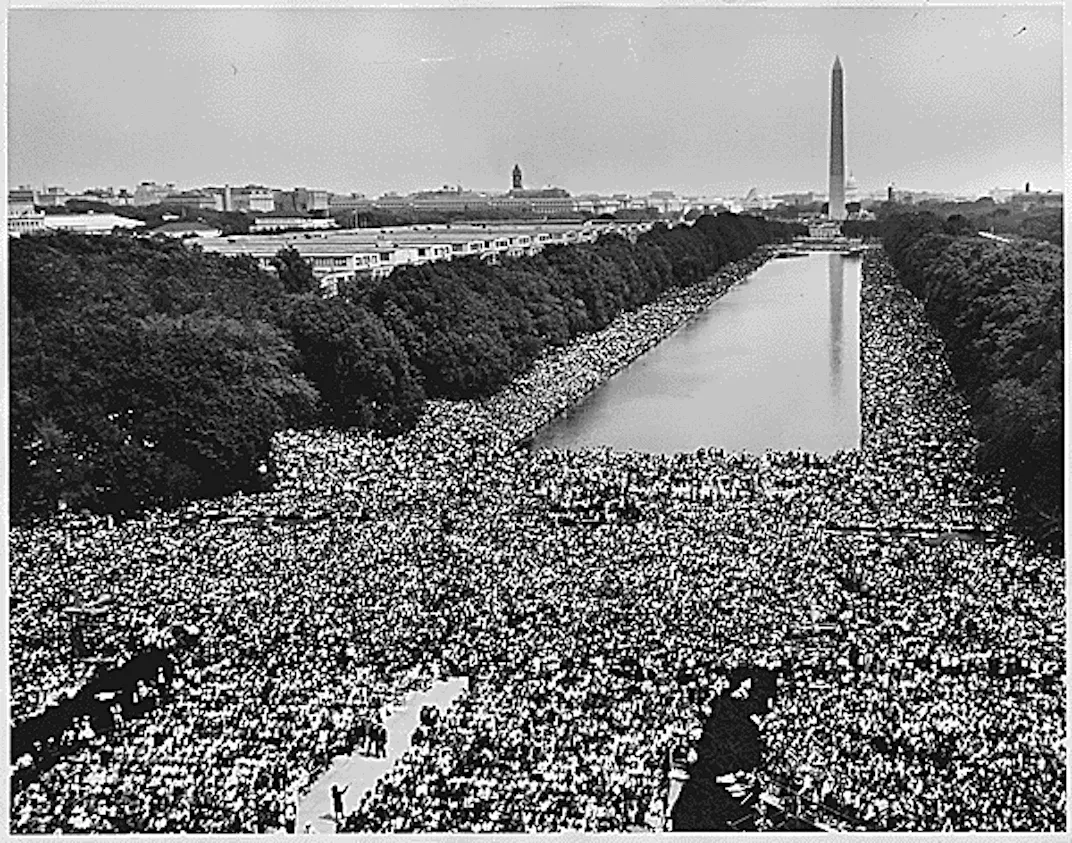

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom – August 28, 1963

Best remembered for Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, this enormous demonstration called for fighting injustice and inequalities against African-Americans. The idea for the march dated back to the 1940s, when labor organizer A. Philip Randolph proposed large-scale marches to protest segregation. Eventually the event came to be thanks to help from Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, Whitney Young of the National Urban League, Walter Reuther of United Auto Workers, Joachim Prinz of American Jewish Congress and many others. The march united an assembly of 160,000 black people and 60,000 white people, who gave a list of “10 Demands”, including everything from desegregation of school districts to fair employment policies. The march and the many other forms of protest that fell under the Civil Rights Movement led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968—though the struggle for equality continues in different forms today.

Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam – October 15, 1969

More than a decade into the Vietnam War, with half-a-million Americans involved in the conflict, the public was increasingly desperate for an end to the bloodshed. To show united opposition to the war, Americans across the U.S. participated in street rallies, school seminars and religious services. The Peace Moratorium is believed to be the biggest demonstration in U.S. history, with 2 million people participating, and 200,000 of them marching across Washington. A month later, a follow-up rally brought 500,000 anti-war protestors to Washington, making it the largest political rally in the nation’s history. But despite the vocal outcry against the conflict, the war continued for six more years.

Kent State/Cambodian Incursion Protest – May 9, 1970

In addition to rallies at the capital, Americans across the country staged protests against the Vietnam War, especially at universities. Kent State in Ohio was one of the sites of demonstrations. When students heard President Richard Nixon announce U.S. intervention in Cambodia (which would require drafting 150,000 more soldiers), rallies turned into rioting. The National Guard was called in to prevent further unrest, and when confronted by the students the guardsmen panicked and fired about 35 rounds into the crowd of students. Four students were killed and nine seriously wounded; none of them were closer than 75 feet to the troops who shot them.

The incident sparked protests across the country, with nearly 500 colleges shut down or disrupted due to rioting. Eight of the guardsmen who fired on the students were indicted by a grand jury, but the case was dismissed over lack of evidence. The Kent State shooting also spurred another anti-war protest in Washington, with 100,000 participants voicing their fears and frustrations.

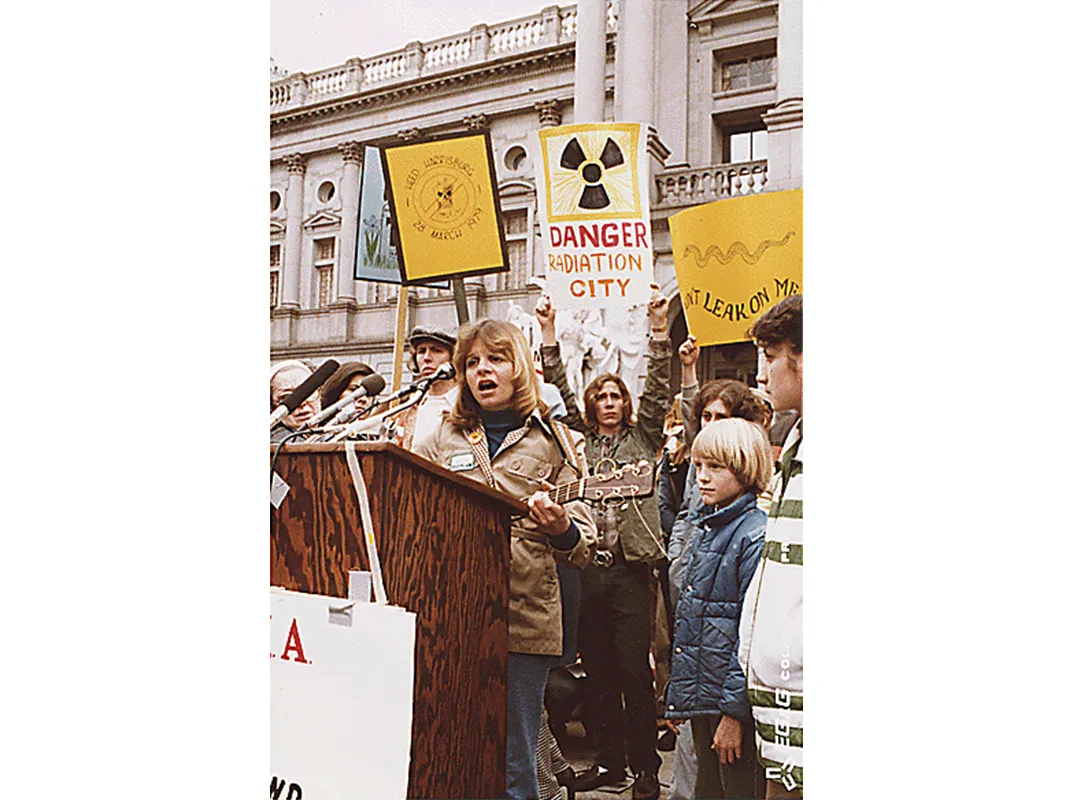

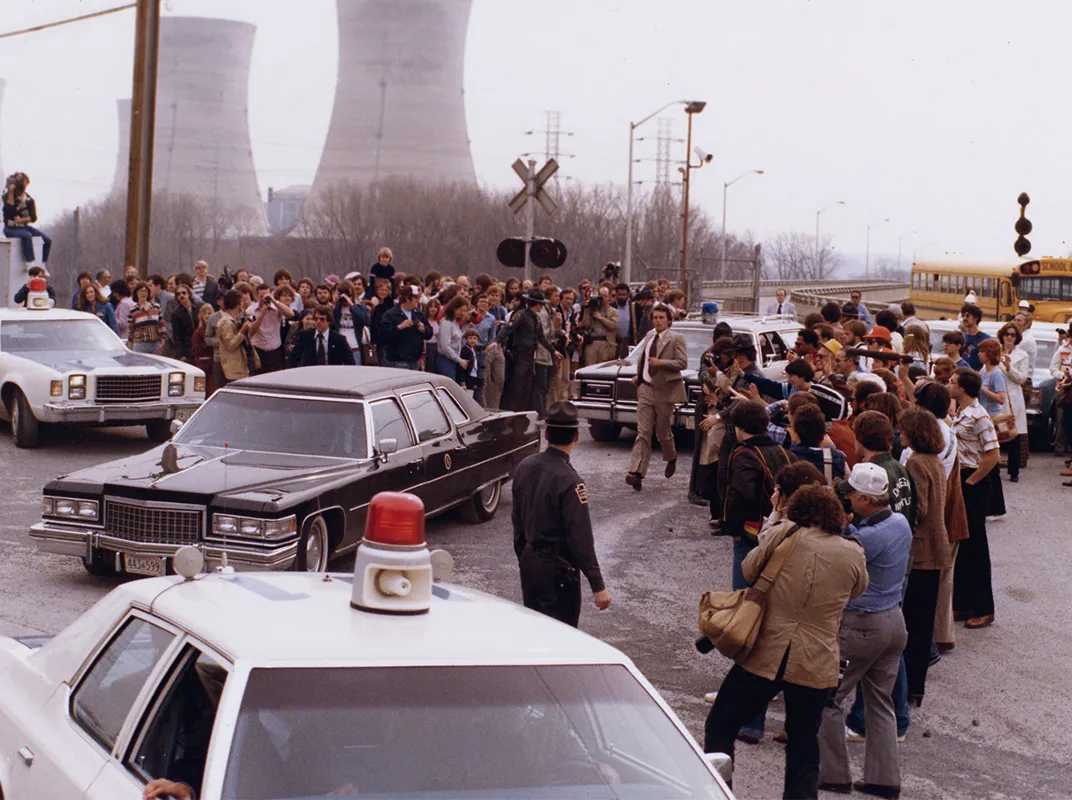

Anti-Nuclear March – May 6, 1979

On March 28, 1979, the U.S. experienced its most serious accident in the history of commercial nuclear power. A reactor in Middletown, Pennsylvania, at the Three Mile Island plant experienced a severe core meltdown. Although the reactor’s containment facility remained intact and held almost all the radioactive material, the accident fueled public hysteria. The EPA and Department of Health, Education and Welfare both found that the 2 million people in proximity to the reactor during the accident received a dose of radiation only about 1 millirem above the usual background radiation (for comparison, a chest x-ray is about 6 millirem).

Although the incident ultimately had negligible effects on human health and the environment, it tapped into larger fears over nuclear war and the arms race. Following the Three Mile Island meltdown, 125,000 protestors gathered in Washington on May 6, chanting slogans like “Hell no, we won’t glow” and listening to speeches by Jane Fonda, Ralph Nader and California governor Jerry Brown.

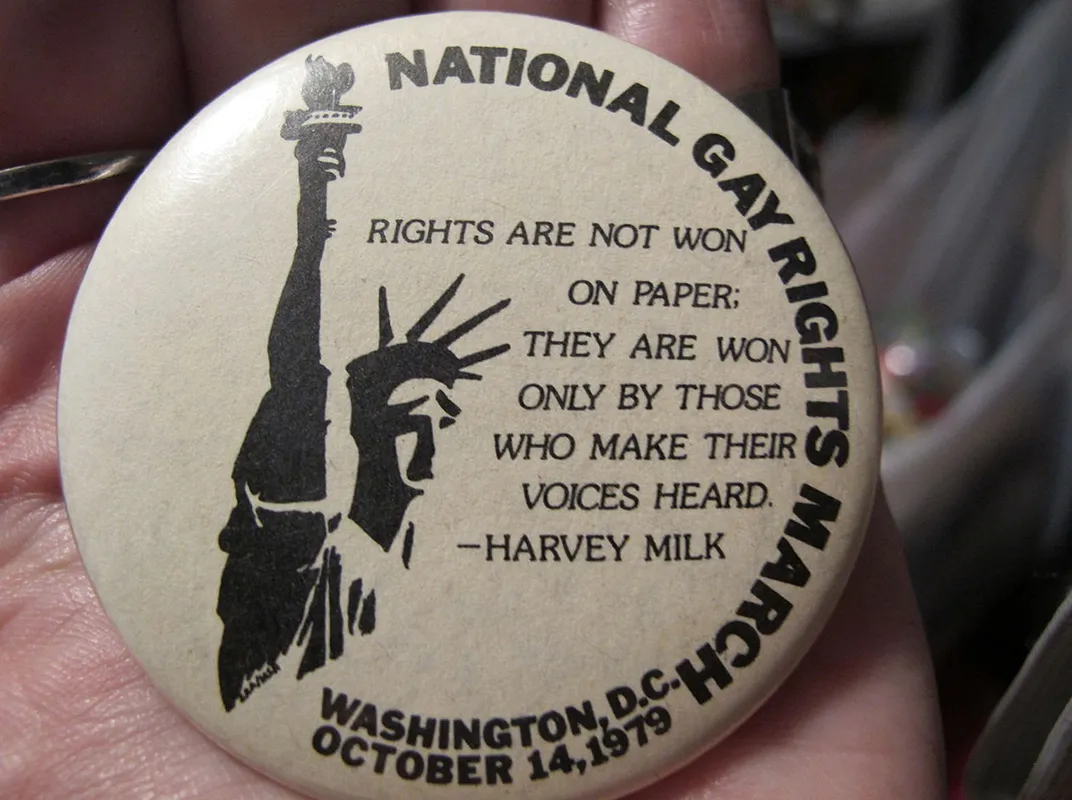

National March for Lesbian and Gay Rights – October 14, 1979

Ten years after the Stonewall riots (a series of LGBTQ demonstrations in response to police raids in Manhattan), six years after the American Psychiatric Association took homosexuality off the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual as a mental illness, and 10 months after openly gay public official Harvey Milk was assassinated, 100,000 protestors marched on Washington for LGBTQ rights. To hold the event, the community had to overcome one obstacle that few other minority groups did: their members could hide their sexual orientation indefinitely, and marching would essentially mean “coming out” to the world. But as the coordinators Steve Ault and Joyce Hunter wrote in their tract on the event: “Lesbians and gay men and our supporters will march for our own dream: the dream of justice, equality and freedom for 20 million lesbians and gay men in the United States.”

A decade later, a second march involved more than 500,000 activists angry about the government’s lackluster response to the AIDS crisis and the 1986 Supreme Court decision to uphold sodomy laws. The movement continued to address issues faced by LGBTQ citizens, culminating with a major victory in June 2015 when the Supreme Court ruled state-level bans on same-sex marriage were unconstitutional.

People’s Anti-War Mobilization – May 3, 1981

The crowd that assembled to protest the Reagan Administration in 1981 was perhaps one of the most tenuous coalitions. The demonstration was co-sponsored by over 1,000 individuals and organizations across the country and they marched for everything from Palestinian autonomy to U.S. involvement in El Salvador. It seemed the march was meant in part to unify all the various groups, according to Bill Massey, spokesperson for the People’s Anti-War Mobilization: “This demonstration is a shot in the arm and will lead to greater unity among the progressive forces in this country.” Unlike the Vietnam protests that sometimes escalated to violence, these casual marchers were described as taking time to eat picnic lunches, drink beer and work on their tans.

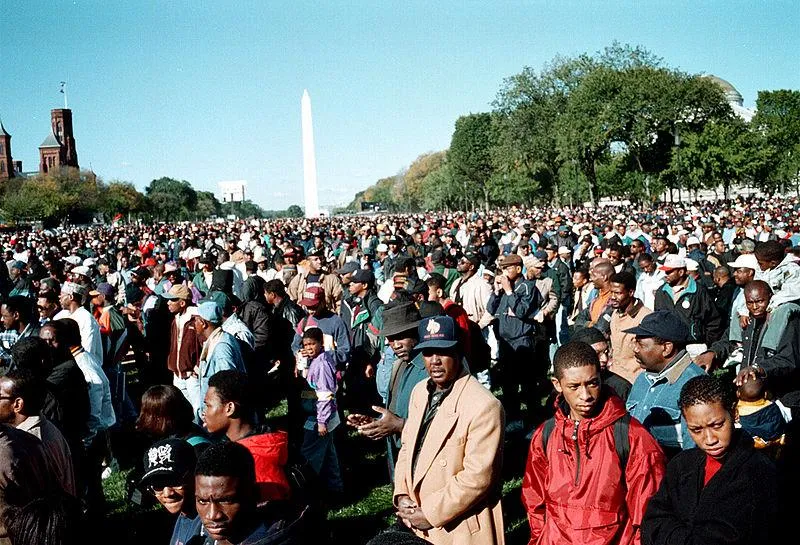

Million Man March - October 16, 1995

Rallying to calls for “Justice or Else,” the Million Man March in 1995 was a highly publicized event with the goal of promoting African-American unity. The march was sponsored by the Nation of Islam and led by Louis Farrakhan, the controversial leader of the organization. In the past Farrakhan had espoused anti-Semitic views, faced complaints of sexual discrimination, and was subject to internecine battles within the Nation of Islam.

But at the 1995 rally, Farrakhan and others advised African-American men to take responsibility for themselves, their families and their communities. The march brought together hundreds of thousands of people—but exactly how many was yet another controversy. The National Park Service initially estimated 400,000, which participants said was far too low. Boston University later estimated the crowd at around 840,000, with an error margin of plus-or-minus 20 percent. Regardless of the specific number, the march helped mobilize African-American men politically, offered voter registration and showed that fears over African-American men gathering in large numbers had more to do with racism than reality.

Protest Against the Iraq War – October 26, 2002

“If we act out of fear and not hope, we get bitter and not better,” civil rights activist Rev. Jesse Jackson told a crowd of 100,000 in October 2002. “Sometimes wars are necessary. The Civil War to end racism was necessary. World War II to end fascism was necessary… But now, we can do it a better way.” The assembled group came in response to the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution, passed by Congress authorizing the war in Iraq. The event was Washington’s largest anti-war demonstration since the Vietnam era and was mirrored by demonstrations in Berlin, Rome, Tokyo, Copenhagen, Mexico City and elsewhere. Despite the vehemence of its participants, a small number of Iraqi-Americans staged a counterdemonstration on the same day, emphasizing the need for U.S. intervention.

In 2003 the U.S. invasion of Iraq began. It continued until 2011 and resulted in the deaths of around 165,000 Iraqi civilians and close to 7,000 American troops.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)