OFFICE OF ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND INTERNSHIPS

Einstein’s “Relatively” Surprising Test Results

Do you prefer low, well-upholstered furniture? Do you like to sleep nude? Do you have a poor poker face? These questions may sound like another kooky BuzzFeed quiz, but they are actually taken from a test entitled “Who Are You?” The test, developed by psychologist William H. Sheldon, categorized people into one of three different body types: endomorph (fat), ectomorph (thin), and mesomorph (muscular) based on their responses to questions about their daily habits, traits, and preferences.

Do you prefer low, well-upholstered furniture? Do you like to sleep nude? Do you have a poor poker face? These questions may sound like another kooky BuzzFeed quiz, but they are actually taken from a test entitled “Who Are You?” The test, developed by psychologist William H. Sheldon, categorized people into one of three different body types: endomorph (fat), ectomorph (thin), and mesomorph (muscular) based on their responses to questions about their daily habits, traits, and preferences.

The prolific writer Aldous Huxley helped popularize Sheldon’s theories in the 1940s and 1950s during a time when both academics and the general public increasingly turned to psychology as a way to study, research, and know the self. Even the famed physicist Albert Einstein took a version of Sheldon’s test, which revealed his preference to remain “inconspicuous” at parties and his difficulty falling asleep if somebody was snoring loudly nearby.

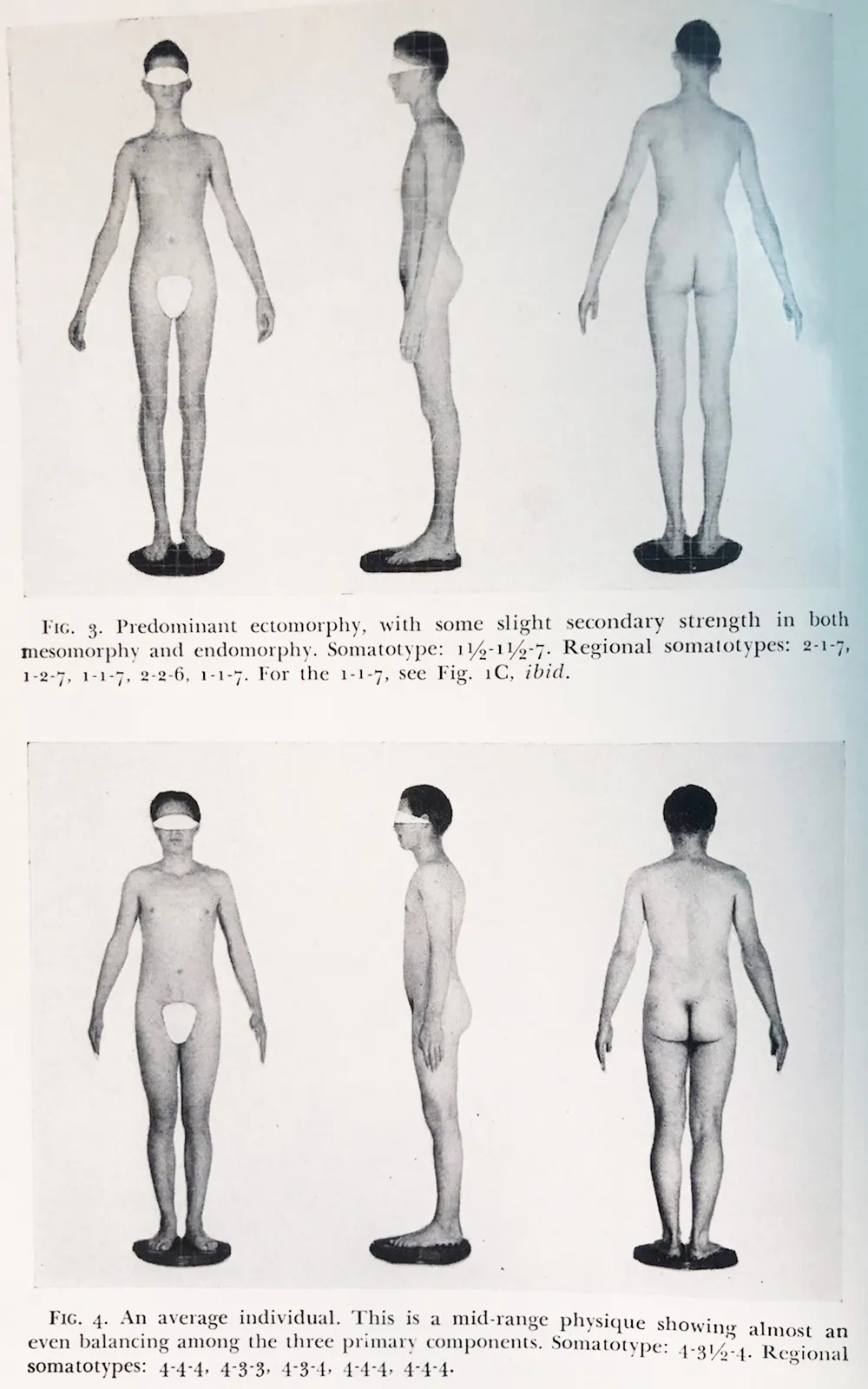

The Smithsonian’s Dibner Library acquired Einstein’s completed copy of “Who Are You” from Mark Plunguian, whose wife Gina was an artist and occasionally served as Einstein’s secretary. She sculpted and painted portraits of Einstein in his Princeton home.

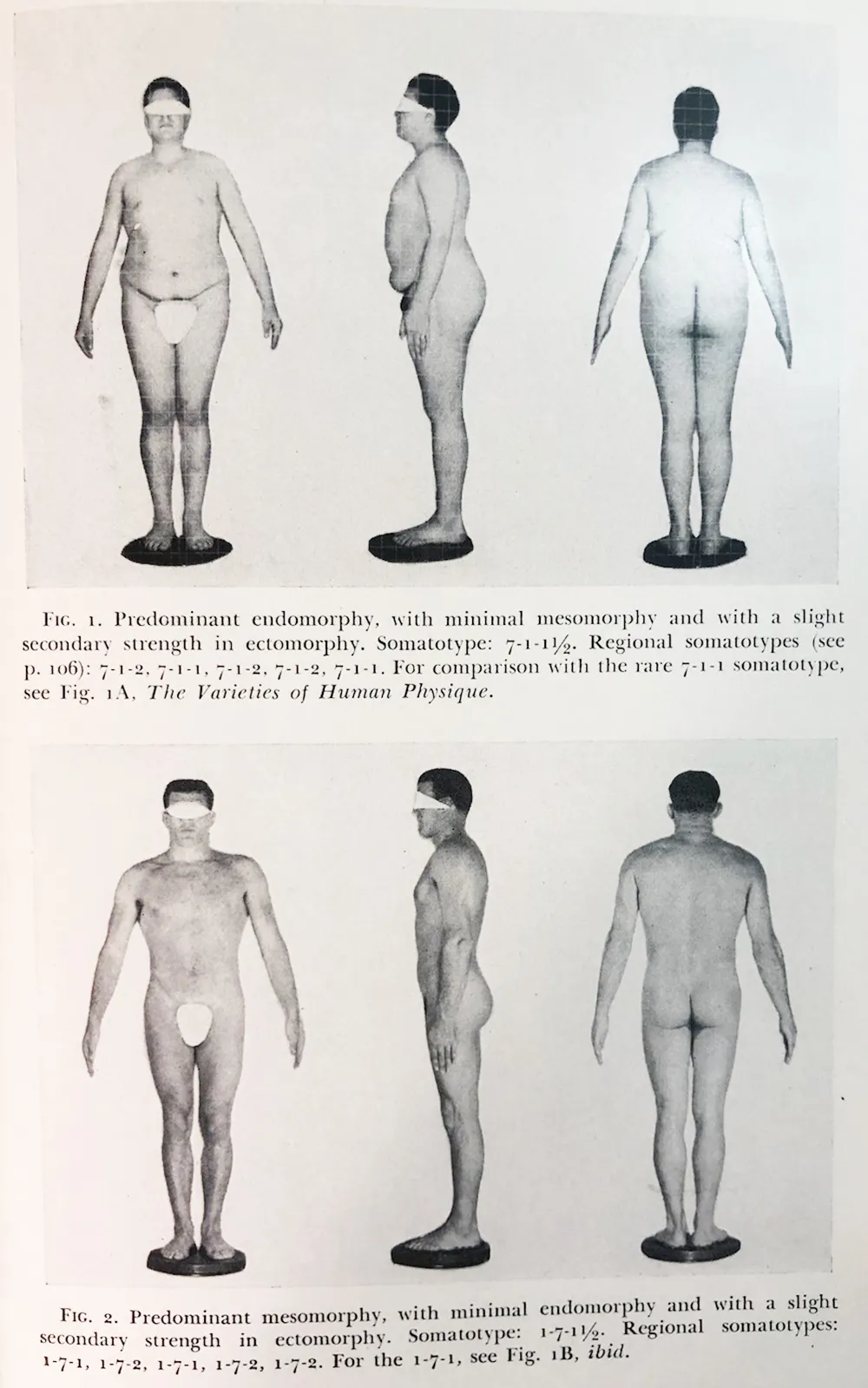

Like many other Americans at the time, she expressed some interest in Sheldon’s theories. Sheldon believed a correlation existed between personality traits and body type, and that better bodies generally exhibited better moral qualities. Asking questions about a person’s propensity to exercise, their eating habits, and their feelings allowed Sheldon to gather data that he then used to advance a theory of human classification based on measurement.

As a eugenicist, Sheldon ascribed to the belief in Social Darwinism and often espoused racist views. Today, he is best known for photographing thousands of naked undergraduate students to gather data on posture and body type—photographs which are (restricted) at the Smithsonian’s Anthropological Archives. “Who Are You?” would have enabled Gina Plunguian to better capture Einstein’s psychological traits through his physiology, and it gives researchers today a fascinating glimpse into Einstein’s life. But it does more than simply teach us about Einstein. It can help us better understand the limitations of mental testing technologies.

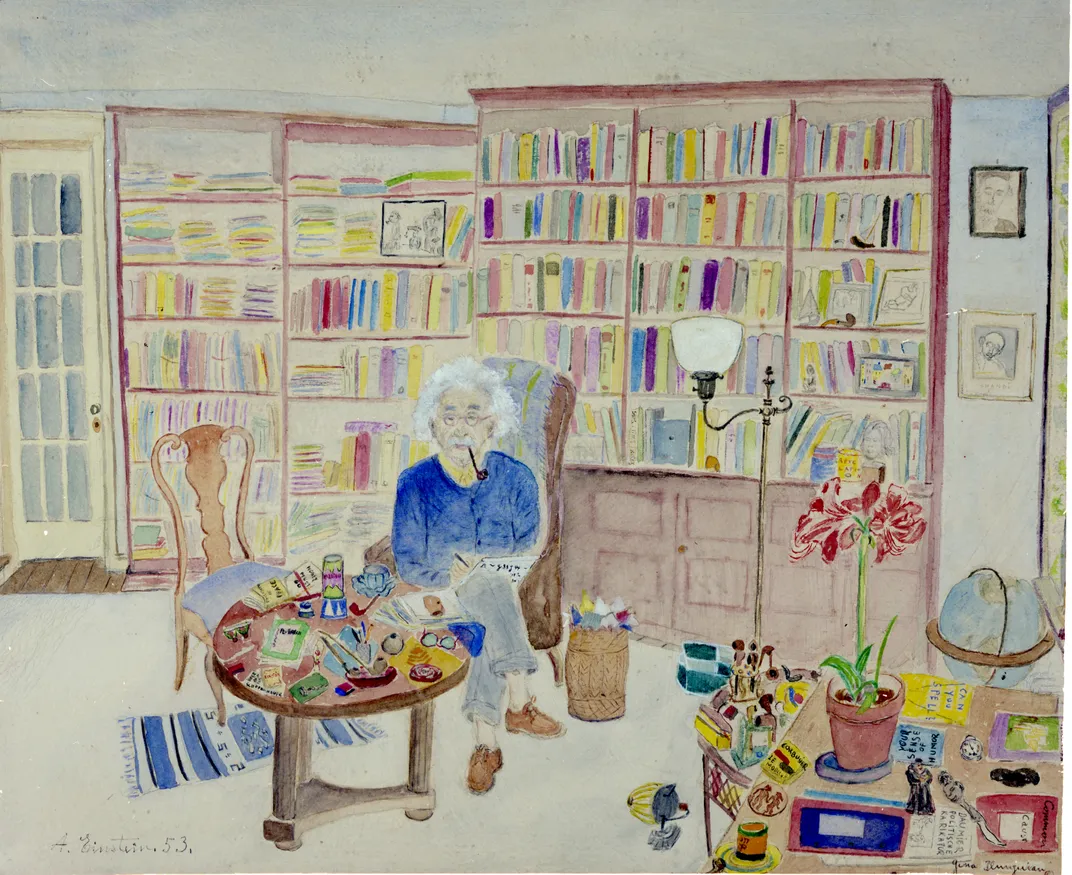

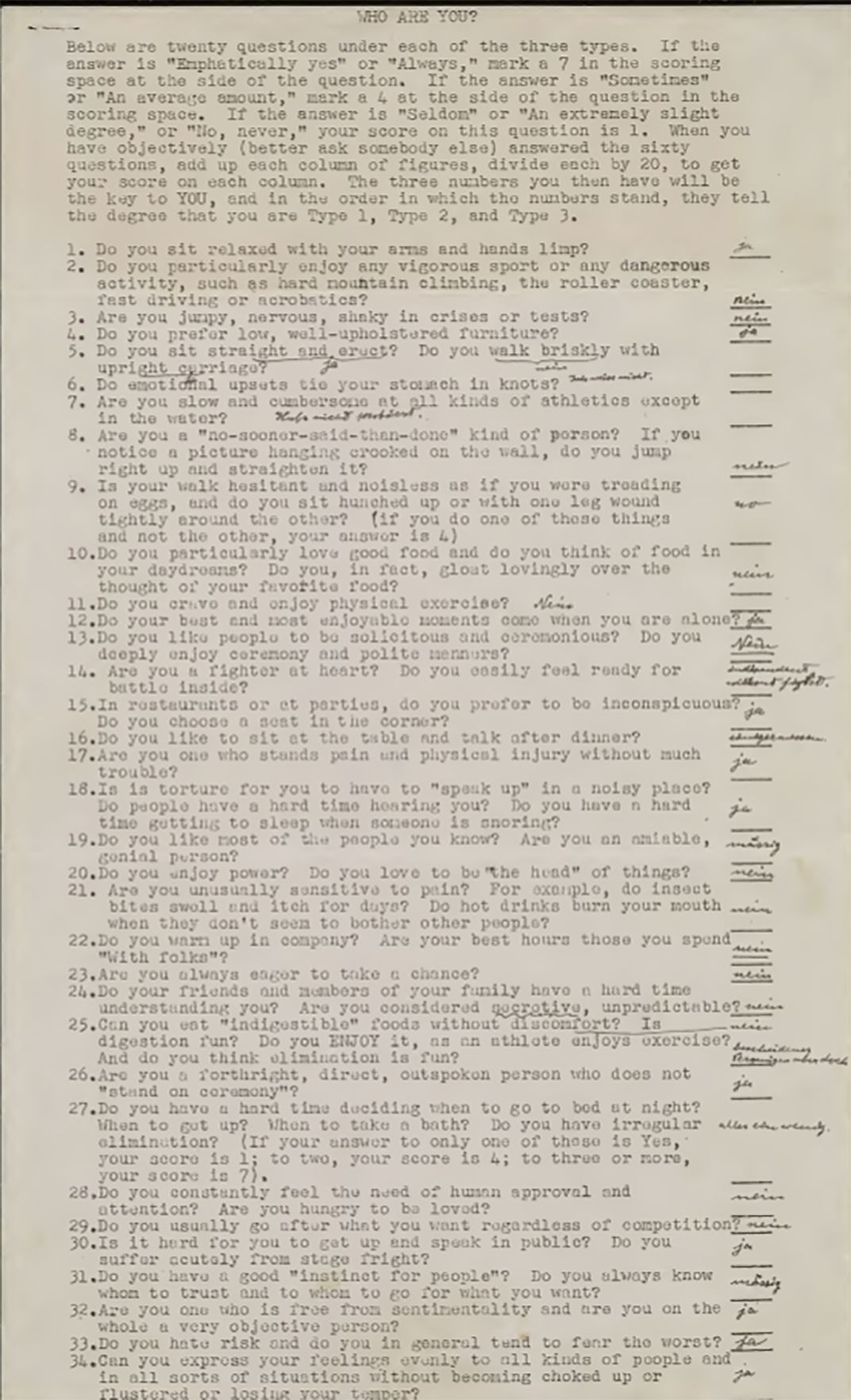

In Sheldon’s taxonomy, mesomorph was the most developed type. But Einstein’s responses do not suggest that he would have been characterized that way. For example, Einstein reported that he didn’t like taking chances or “being at the head of things,” and disliked physical exercise. He also shared intimate details about his (in)digestion and bodily functions. Moreover, he did not follow the test’s directions, which instructed that the person taking the test rate themselves on a scale of one to seven, one being “seldom” and seven being “emphatically yes.”

These numbers would have allowed experts to obtain accurate and precise measurements to easily categorize each subject. Instead, Einstein wrote ja (“yes”) or nein (“no”) for the majority of the questions, scribbling notes and annotating the test in places where he felt a more nuanced response was required. Because he did not follow the directions, it’s impossible to know how Sheldon would have classified Einstein.

But the exam reveals something else: it shows that Einstein felt the test was limited, and he was compelled to shape and remake this scientific tool in order to give Plunguian a more accurate description of himself. Intentionally or unintentionally, he subtly suggested the limitations of this scientific instrument.

Sheldon felt that scientific tools and methods—like anthropologically taking photos to determine body type or creating a psychologically validated test to sort people into narrow categories—could better engineer the human race. He designed a test to produce a quantifiable, easily comparable numerical value to classify people and promote his eugenicist agenda. Einstein resisted this easy categorization, highlighting the limitations of psychological instruments, the assumptions and biases built into supposedly objective tests, and the politics animating scientists’ work. To be sure, not all tests are flawed as Sheldon’s. But every test is produced in a specific historical context, and experts’ biases and beliefs necessarily inform the information these tools produce.

Today, more and more institutions are beginning to recognize the limitations of tests and the ways in which these assumptions have adversely impacted the most marginalized members of our society. Many colleges are now making the SAT optional, and even Harvard dropped its standardized test requirement for 2021.

While these dramatic changes to the American testing landscape reflect the need to maintain social distancing and the exigencies of COVID-19, universities and testing agencies are acknowledging the way tests perpetuate existing social inequalities, finally reckoning with the eugenicist legacy of their origins. Rejecting tests that classify and rank people based on “scientific” measurement is a necessary step in both the viral and racial pandemics we are currently fighting.

Protecting against the violence of taxonomy requires that educators and administrators find better ways to ensure that opportunities are distributed equitably. Failure to make these changes risks misidentifying the next Einstein. But even more important than finding scientific geniuses, democracy itself is threatened when only part of the population is provided with a strong educational foundation, and when flawed tests are the primary way of distributing opportunity.