NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

A Retro Look in the Archives Reveals Past Views on Language Derogatory to Native Americans

Although current views may point to “political correctness” for changes in language and terminology, by looking back through historical documents, it’s quite clear that this is not something new.

:focal(2421x1983:2422x1984)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9d/c3/9dc354ad-af55-40cc-bf08-d03249bd1df5/ncai_delegates.jpg)

Language changes and evolves over time. Words fall out of favor and new words and phrases emerge. This sometimes occurs because of an understanding that certain words are racist, derogatory, or harmful to others, but even as some things change, there are also things that stay the same. As primary researcher on the National Museum of the American Indian’s Retro-Accession lot project, I have read through tens of thousands of documents spanning the last one hundred years and have been able to see the transformation in language and attitudes over time regarding Indigenous peoples. Current views may point to “political correctness” for changes in language and terminology, but by looking back through historical documents, it’s quite clear that this is not something new.

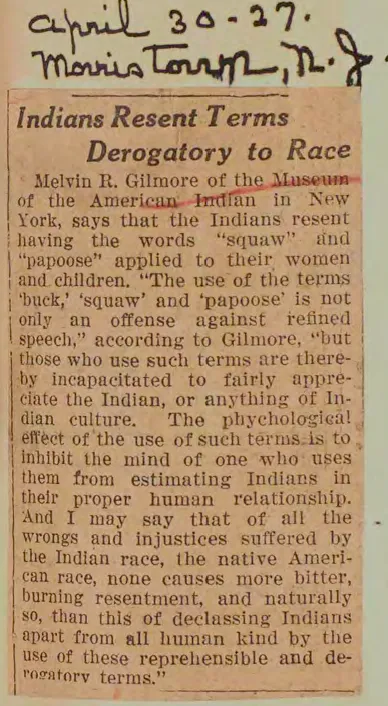

A good example of this can be found among the records of the Museum of the American Indian-Heye Foundation (1916-1989) in the museum’s archive center. The Museum of the American Indian, which became the National Museum of the American Indian when it was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution, maintained scrapbooks that offer a glimpse into museum activities of the time, as well as articles about Native American issues of the period. One scrapbook contains a 1927 article quoting Melvin Gilmore, an ethnobotanist on the museum’s staff, that highlights the resentment Native people felt about terms derogatory to race. What is striking about this article is that it was written over 90 years ago but could be something published today. Even at that time, Gilmore was aware that using certain language to describe Native peoples was not only disrespectful, but also treated Native Americans as “the other” rather than part of our shared humanity. He was also aware of the psychological impact that certain language had on Native individuals, an issue that we are still grappling with today regarding stereotypical Native imagery as well as language.

While some people have started to fully grasp the harm that can be caused by offensive language, the conversation continues nearly one hundred years later. Recent changes in the names of sports teams and vacation resorts are a step in the right direction. However, it is not only important to learn which words are offensive, but also why using terminology preferred by Indigenous people is important. As Gilmore stated back in 1927, using harmful language is disrespectful to Native peoples’ humanity and does not allow for true appreciation of their cultures.

While we want to steer clear of words deemed offensive by Native peoples we also want to respect the diversity within Indigenous groups throughout the Americas. One of the most frequent questions we get at the NMAI is “Do you say Native American or American Indian?” At the museum we tell visitors that both terms are currently acceptable. Perhaps over time as language continues to evolve this may change, but today either of these terms can be used. However, we also tell visitors that the preference is the term that a person uses to refer to themselves. This might be the name of their tribal nation (or nations) or community, or in more general terms it might be Native American, Indigenous, American Indian, or First Nations. It’s an individual preference that can be influenced by geographic region, generation, or personal identity. Since language is always shifting and changing, there is not just one term that can fully reflect all points of view among those being named. When it comes to personal interaction with a Native individual, ask them their preference; the same way in which you might ask someone how to pronounce their name or whether they prefer a nickname. Plus, a bonus is that this strategy can be applied to all people of any background, gender, or race.

The museum continues to educate people as Gilmore once did on the harmful history of derogatory phrases, but we also recognize our responsibility in dealing with our own legacy of outdated terminology and racist language present in our catalog records. Gilmore’s views did not necessarily represent the view of all anthropologists and museum professionals of his time. Museum catalogs are littered with terms now deemed racist, pejorative, or outdated. Some of these terms are names that were used by non-Natives to refer to a particular group or perhaps the name that one group used to refer to another group. For the past fifteen years, the museum has been working to update the terminology in our catalog to the preferred names used today by Indigenous tribes and communities throughout the Americas. This task has become especially important as we strive to make our collections information more accessible by posting our collections online, except those items deemed culturally sensitive which may be presented without images or with limited information. There is more work to be done but this effort is a step towards more inclusive and thoughtful descriptions of our collections to better serve our Indigenous constituents and the general public.