NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

Five Ideas to Change Teaching About Thanksgiving, in Classrooms and at Home

Between Thanksgiving and Native American Heritage and Month, November is go-time for teaching and learning about Native America. Here, parent and museum educator Renée Gokey shares simple ways to make the responsibility less daunting. In addition to briefly describing strategies for learners K–12, Renée links to teaching resources from the museum and other organizations. And she notes that students can use Thanksgiving and their new tools for thinking about culture to learn and share more about their own family’s history and traditions.

:focal(1076x614:1077x615)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Theresa_Secord_maize_basket_26-1694_12x7.jpg)

As a mother of elementary-aged children and an Indigenous educator at the National Museum of the American Indian (and now at home), I know that it can be challenging for parents and teachers to sort through books, Pinterest images (I highly suggest you not get your teaching ideas there), and online lesson plans about Native Americans. How do you know what is appropriate? And where can you find more accurate and authentic resources?

Added to this good challenge of bringing more Native perspectives to your teaching is the need to move past overused and simplistic curriculums for teaching about Native cultures. One common approach in early elementary classrooms during a “Native American Unit” is to center lesson plans around food, clothing, and shelter—what I call the trilogy approach to learning about Native Americans. These topics seem like simple ways to teach about Native American cultures. But would you want your home to be called a shelter? The word suggests “primitive” cultures that did not have complex and sophisticated ways of life that varied immensely in diversity.

The National Museum of the American Indian has a guide called the Essential Understandings that provides key concepts and language to frame your thinking about Native Americans before you get started. The specific strategies below build on those concepts to help deepen your teaching and bring more meaningful content about Native Americans to your current education setting—be that a dining-room table or a classroom—during Native American Heritage Month and throughout the year.

Food is a great place to start. A worksheet that asks, “What did the Indians eat?” isn’t.

Instead of a long list of foods—and, when we’re talking about the Americas, that list is lengthy indeed, with about 60 percent of the world’s foods originating in Native agriculture throughout the Western Hemisphere—explore just one or two foods in depth.

Questions you might ask yourself to begin include, Where did a food originate? And how long has it been grown by that specific tribal community? For some cultures, oral traditions say the people come from the food itself, as in this Maya corn story. What might that say about the longevity and importance of the relationship between the Maya people and their mother corn?

Instead of a nameless and generic “Indians” approach, explore the ways that people of a specific culture adapted agriculture for their environment. The museum’s teaching poster Native People and the Land: The A:Shiwi (Zuni) People looks at the community’s reciprocal relationship with the land in the semiarid climate of New Mexico and especially at a centuries-old farming technique known as waffle gardens.

Finally, when teaching about Native cultures, change the language of your questions and discussion from past tense to present. For more ideas on how to get started, check out Native Life and Food: Food Is More Than Just What We Eat, one of the museum’s Helpful Handouts: Guidance on Common Questions. For the youngest children, make an easy corn necklace and learn more about the rich corn traditions of Native peoples. You’ll find an activity sheet and video demonstration here.

Make sovereignty a vocabulary word in your classroom.

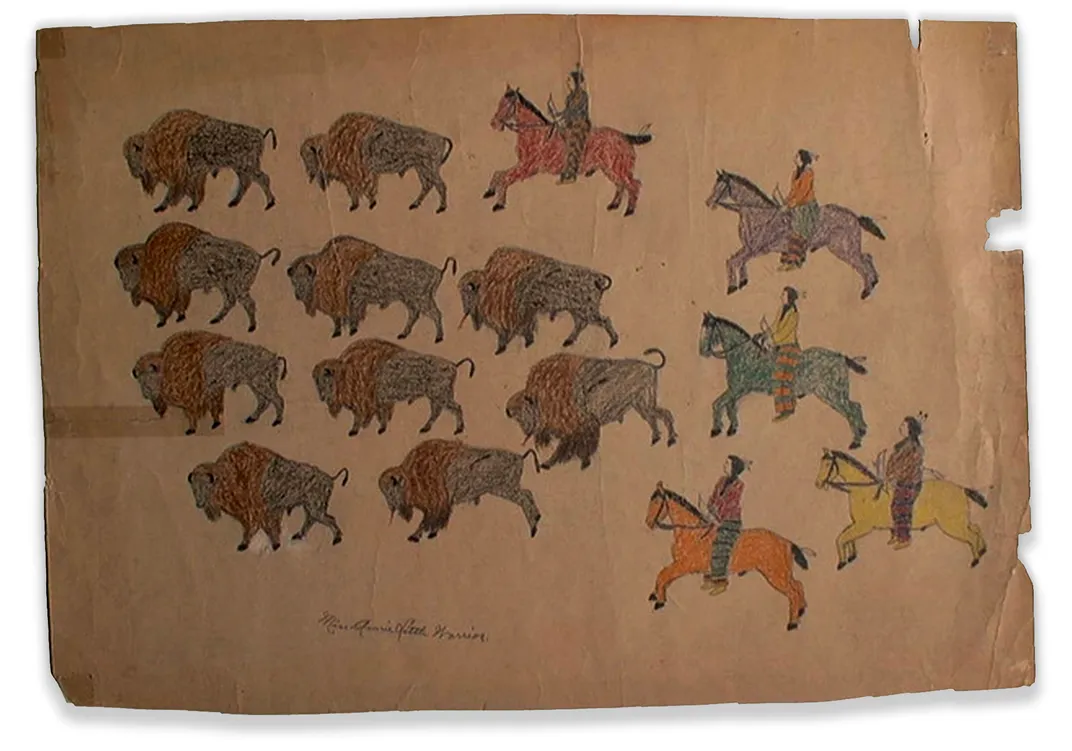

In relation to food, sovereignty is the ability to feed yourself and your family in keeping with your history and culture. Teaching about food sovereignty and understanding how Native food cultures were systematically destroyed gives us several key understandings to American history and to touchpoints already in the curriculum. “Westward Expansion,” for example, can be explored through Lakota perspectives when students are learning about the importance of bison to ways of life, clothing, and cultural values. You’ll find guidance for teachers and students in the section Connecting to Native Histories, Cultures, and Traditions on this webpage.

For grades 4–6, explore the rich tradition of clothing and the meaning inherent in the prolific work of women in the museum’s teaching poster A Life in Beads: The Stories a Plains Dress Can Tell. Or show this video on the Native peoples and cultures of the Pacific Northwest to share the many ways that the foods we eat matter.

Students in grades 9–12 grades can learn about a landmark court decision and the civil rights era for tribes of the Pacific Northwest in their efforts to maintain their treaty rights in this powerful lesson.

And, use the museum’s Native Knowledge 360° resource on food sovereignty.

Supporting websites from beyond the museum include North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems. Led by Sean Sherman, this organization reinvigorates and connects Native chefs and other people working in food sovereignty. The White Earth Land Recovery Project is another example of Indigenous food revitalization happening around the country in Native communities and how you can support the effort. You can also follow the example of the museum’s award-winning Mitsitam Native Foods Café and research shopping from Indigenous growers and ranchers.

Bring Native voices into your teaching.

Students can hear Native people’s perspectives on their history and experiences by reading books and articles by Native authors or listening to programs like the Toasted Sister podcast. If you’re looking for books, a very good place to begin is the list of titles recommended by Dr. Debbie Reese (Nambé Pueblo). Dr. Reese created and edits the online resource American Indians in Children’s Literature.

Share more about Native Peoples’ vibrant, ongoing traditions of giving thanks throughout the year with the museum’s teaching poster American Indian Perspectives on Thanksgiving. Or read about the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving address, a tradition spoken at important gatherings year round.

For younger children, read the picture book We are Grateful by Cherokee author Traci Sorell. Sorell wrote her story, which shows the full year of Cherokee gratitude, in Cherokee and English so that kids can see the Cherokee writing system.

Attend an online professional development program.

This online teacher workshop series was hosted by the education department at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian and delivered to more than 700 teachers. It examines popular historical and contemporary images of Native people and how they have informed our understanding of the holiday. Learn about inquiry strategies for primary and secondary sources, plus Native Knowledge 360° education resources that include Native perspectives to help support your teaching of more complete narratives about Native people in the class throughout the year. Here is the two part series:

A couple of years ago, PBS featured the museum’s professional development workshop around teaching Thanksgiving. You can see the short video How Teachers are Debunking Some of the Myths Of Thanksgiving on the PBS Newshour website.

And for families, try this cooking show from Aicha Smith-Belghaba, a Haudenosaunee and Syrian chef from the Six Nations of the Grand River in Canada.

See Thanksgiving as a chance to share your family’s unique history and traditions, too.

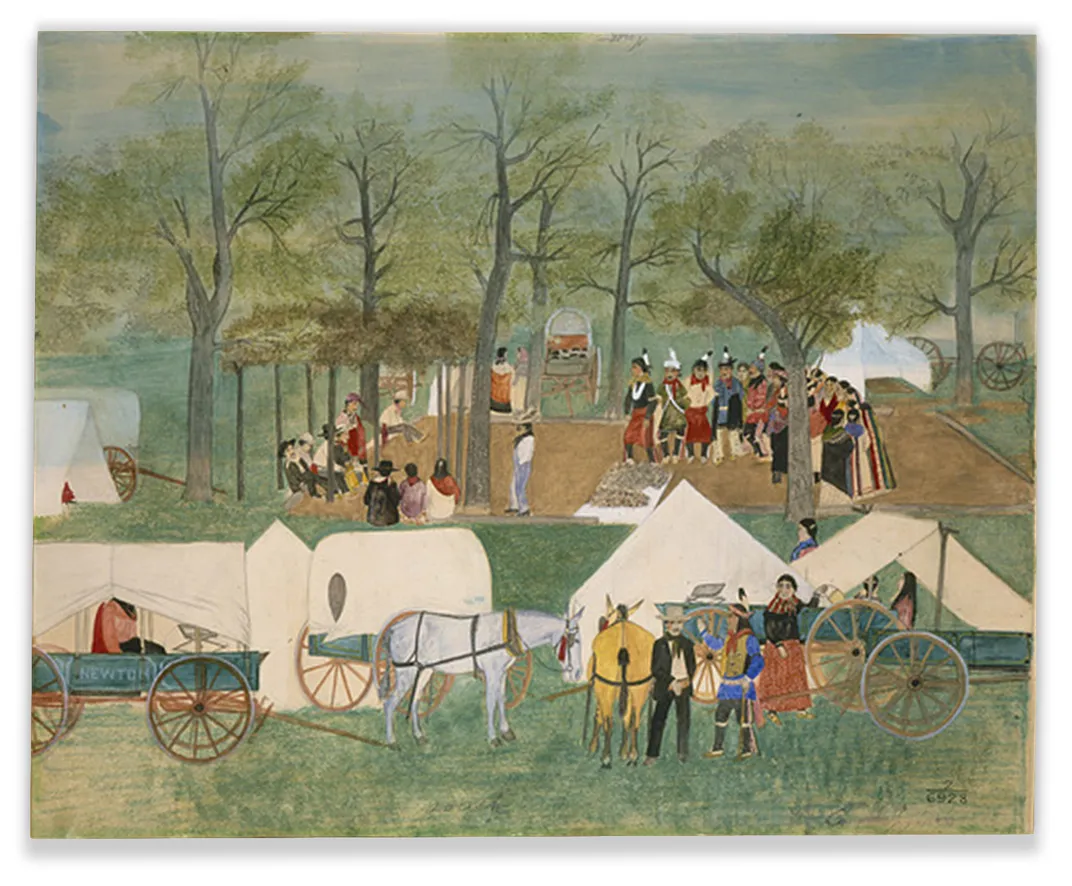

Talk about the actual 1621 event that’s been come to be known as Thanksgiving, rather than the mythical one. Did you know that the First Thanksgiving between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims may have actually had more to do with diplomacy than a simple feast? Learn more about the actual event in this impassioned short essay by a museum intern, published by Smithsonian Voices. Use our study guide Harvest Ceremony: Beyond the Thanksgiving Myth as a teaching resource.

Honor your students’ and your own family’s food traditions. Story Corps’ Great Thanksgiving Listen is a terrific guide to collecting your family’s oral history. Interview family members on the phone or over the Internet if that’s the best way to keep everyone safe.

And think about traditions you may take for granted. Pumpkin is a traditional Shawnee food. There’s a Shawnee pumpkin that some families still grow—it’s smaller than most orange pumpkins, and a light grayish blue. Pumpkin is called wapiko in Shawnee. Wapiko’nekawe is the term for the pumpkin dance. Still practiced today, this dance pays tribute to the pumpkin and shows how important it is to Shawnee people.

Some Shawnee families won’t a carve pumpkin. Our family doesn’t follow that practice, but we don’t let any part of the pumpkin be wasted. We roast the seeds with olive oil and salt, and boil or bake the pieces cut away during the carving for pumpkin bread or pie. Historically, pumpkin was cut into rings and smoked over the fire for the winter. Fresh pumpkin can also be cooked by skinning it and boiling it down. It will release its own water, but some water will need to be added, along with a little grease. When it’s close to done, add a little sugar.

All of us have food histories worth exploring. During this year when so many things look different, take a new perspective on your family’s history and traditions through food. Try a family recipe together and have your children write it down to share. Or make a short video to send to family members you can’t see in person.

Above all, remember to give thanks for each and every day, a gift that is not guaranteed to any of us.

Ed. Note: This article was originally published November 13, 2020 and has been updated with links to new educational content for teachers.

Renée Gokey (citizen of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma) is the teacher services coordinator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.