NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

Spotlight on Collections: Expanding Both What We Know and What’s Available Online

The National Museum of the American Indian has taken a major step toward making our collections more widely available: We have posted all of the museum’s ethnographic and contemporary art collections to the Smithsonian’s collections search center, more than tripling the number of our object records online. Equally important, a long-term, multi-institutional project to reconstruct objects’ acquisitions history is adding significantly to what we know about the collections, the history of the museum, and collecting practices over time.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/1655003_Basket_and_card_2.png)

The National Museum of the American Indian has taken a major step toward making our collections more widely available: We have posted all of the museum’s ethnographic and contemporary art collections to the Smithsonian’s online collections search center. Last week, records for some 38,000 objects and sets of objects were available on the search site. Now, more than 122,000 records are available. Records include the known history of an object, its function, the materials used in its construction, and images when appropriate. Culturally sensitive items are not included or may be presented without images or with limited information. More information about that commitment is given in the museum’s Statement on Online Collections and Culturally Sensitive Collections.

Part of the work behind this major undertaking has involved updating records with information we’re finding during the museum’s Retro-Accession Lot Project to reconstruct the collections’ acquisition history. This project, which began in 2010, addresses the fallacy that the museum’s collections were largely undocumented. Its goal is to locate collections documentation and retroactively implement an accession lot system—a numbering system used to connect an object or set of objects with their source and a specific acquisition event. With this information we can begin to rebuild an object’s provenance, or the record of its ownership.

Now in its tenth year, the project has changed significantly what we know about the museum’s collections. Our work has expanded from systematically reviewing the museum’s archives and matching documentation to objects and groups of objects; we are also seeking out archival records at other institutions, conducting genealogical research on the individuals involved, and reconstructing the history of our predecessor institution, the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation, to better understand the museum and collecting practices over time.

As a result of these efforts, we have a much clearer understanding of when and how objects entered the collections of the Museum of the American Indian through purchases, field collections, excavations, gifts, or exchanges. In addition, thousands of names of individuals—Native makers or owners of objects, anthropologists, archaeologists, and dealers—who were never before associated with our collections have been added to our records.

As you look through the museum’s collections online you will see new, updated information beyond what is available from the original catalog cards, including information and connections we never dreamed of or are only now beginning to understand. Here are a few of our discoveries:

The Western Mono coiled basket jar shown above entered the collections of the Museum of the American Indian in 1929 as a gift from Homer E. Sargent Jr. (1875–1957). The original catalog card includes only Sargent’s name as the collector and donor. However, Sargent’s original catalog information, which sat elsewhere in our archives, indicates that this basket was made by Mary Burkhead, a Western Mono woman from North Fork, California, and acquired from her around 1900. The basket was part of the collection of Lucy A. Peckinpah (1840–1920) of Napa, California, until Sargent purchased it from her estate in 1921. With this additional information, two previously unknown individuals are now associated with this basket, including the Native artist.

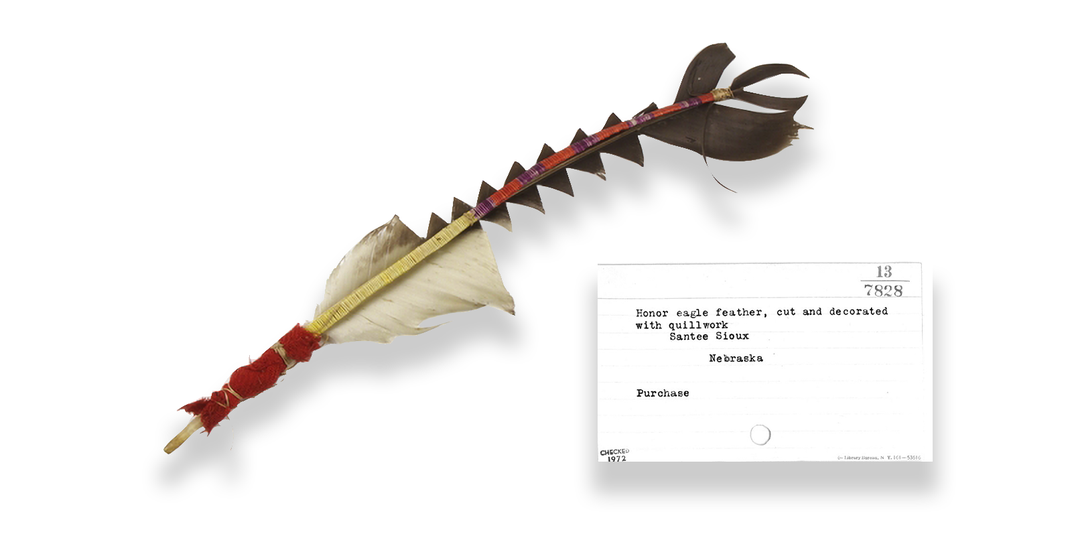

This honor feather with quillwork decoration is another example. Our original catalog records simply list it as a purchase in 1925. However, documents located in the Melvin Gilmore Papers at the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan make clear that the feather was purchased by Museum of the American Indian staff member Melvin Gilmore from Mrs. Mary B. Riggs (1839–1927), whose husband Alfred ran the Santee Normal Training School in Santee, Nebraska. Mrs. Riggs noted that the feather originally belonged to Artemas Ehnamani (1825–1902), a Dakota man who was arrested and imprisoned during the Dakota War of 1862. Ehnamani was sentenced to death but ultimately pardoned by President Lincoln. Ehnamani later became a Presbyterian minister in Santee, Nebraska, where he met Mr. and Mrs. Riggs.

As referenced in earlier posts, the Retro-Accession Lot Project led us across the globe to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. We have partnered with Te Papa to digitize and transcribe the sale ledgers of William Ockleford Oldman, an early-20th-century dealer in London, England, who sold ethnological and archaeological objects to museums all over the world, including the Museum of the American Indian.

In 1909 George Heye, the founder of the Museum of the American Indian, purchased this Haida twined and painted bark cape. The cape was made in Haida Gwaii (the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia), but the original catalog card does not include a source for the purchase. Analysis of the Oldman sale ledgers has begun to fill in the gaps. We now know that Oldman acquired this cape in February 1909 from the J.C. Stevens Auction Rooms in London and sold it to Heye in June of the same year, along with other objects. How the cape made its way from British Columbia to England remains unknown, but we have a starting point for research to further investigate its history.

These are a few examples of discoveries we have made, but there are thousands more stories in our collections. You can read about the Retro-Accession Lot Project on the Smithsonian Collections Blog and at the Transcription Center, where there are opportunities to take part as a Smithsonian Digital Volunteers. We’ll continue to spotlight our research with future posts, and we invite you to explore the museum’s collections online to learn more.