NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

The Treaty that Reversed a Removal—the Navajo Treaty of 1868—Goes on View

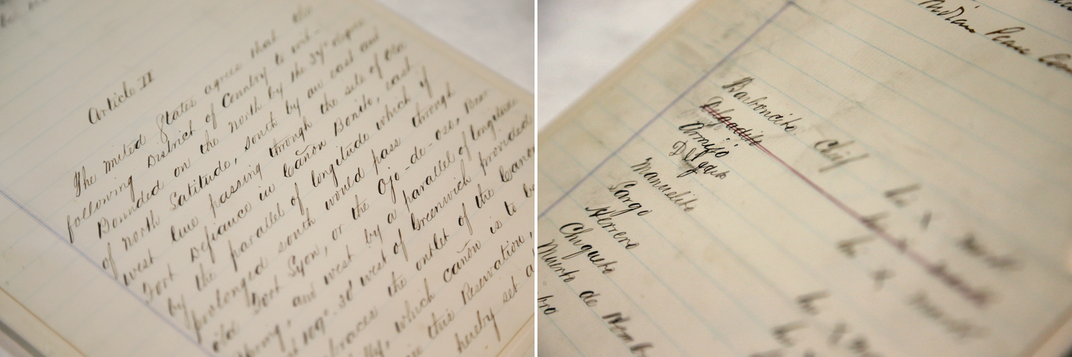

Written on paper from an army ledger book, the Navajo Nation Treaty reunited the Navajo with a portion of the land taken from them by the U.S. government. Between 1863 to 1866, in an event that became known as the Long Walk, the United States forced more than 10,000 Navajo from their homelands to a resettlement camp at Bosque Redondo, 300 miles to the east. But the Navajo made an eloquent case to return home and in 1868 negotiated a treaty that reversed their removal. The original treaty is on view at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., through early May.

:focal(607x378:608x379)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Treaty_of_1868_1_copy.png)

“The U.S. government does not sign treaties with states. They sign treaties with nations around the world. The Navajos are a nation.” —President Russell Begaye, Navajo Nation

On February 20, 2018, more than 100 citizens of the Navajo Nation convened at the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall to take part in the installation of the Naaltsoos Sání, or Navajo Treaty of 1868, in the exhibition “Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations.” Kevin Gover (Pawnee), director of the museum, welcomed the Navajo guests with opening remarks. Navajo Council Delegate Steven Begay then introduced himself in the Navajo language, sang a traditional song “to acknowledge all the lives lost” in the shared history of the Navajo Nation and the United States, and said a Navajo blessing-way prayer.

Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye gave the keynote address to mark the unveiling of the treaty. President Begaye acknowledged the National Archives, the National Museum of the American Indian, and his people. “This treaty represents [that] we are a nation. Negotiations occurred to allow the Navajo to return to the Four Sacred Mountains in Diné Bí Kéyah (Navajo Land). This treaty represents we will always be living within our Four Sacred Mountains.”

The final speaker was Michael Hussey, representing the National Archives and Records Administration, who said, “The mission of the archives is to preserve documents of value. Sixteen million documents are in the National Archives. Collaboration with the National Museum of the American Indian here and in New York has been fruitful to us to make sure documents are seen by those they speak most loudly to.”

In May the treaty will be moved to the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, Arizona, in time for the Navajo Nation to commemorate the 150th anniversary of its signing on June 1. It will be the first time the treaty will be displayed in a tribal museum.

In 1863, the U.S. Army began removing more than 10,000 Navajo people from their extensive homelands in what is now the Four Corners region of the American Southwest to Bosque Redondo, Hwéeldi in the Navajo language, in eastern New Mexico. The 300-mile forced march of the Navajo from their homelands into internment has become known as the Long Walk.

The army continued to intern bands of Navajo resisters until 1866, when Major General James H. Carleton ordered that no more prisoners should be sent to the camp. The land at Bosque Redondo had proved unsuitable for farming, and the army could not provide for the Navajo people already held there.

In 1867 Congress established the Indian Peace Commission to find less costly means than war to bring American Indian resistance on the Plains to an end. In April 1868 a delegation of Navajo leaders traveled to Washington, D.C., to petition President Andrew Johnson to release of their people and return their homelands.

During treaty negotiations at Bosque Redondo in May, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, a member of the peace commission, proposed that the Navajo Nation should move to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) instead. The Navajo leader Barboncito replied, “Bringing us here has made many of us die, also a great number of our animals. Our Grandfathers had no idea of living in any other place except our own land, and I don't think it is right for us to do what we were taught not to do. When the Navajo were first made, First Woman pointed out four mountains and four rivers that was to be our land. Our grandfathers told us to never move east of the Rio Grande River nor west of the San Juan River. . . . I hope to God you will not ask me to go anywhere except my own country.” The Navajo prevailed.

On June 1, 1868, Navajo leaders signed their new treaty on pages cut from an army ledger book. The Navajo became the only nation to use a treaty to reverse their removal and return to a portion of their homelands.

“The elders say we don’t talk about what happened to us,” Navajo Nation Vice President Jonathan Nez said Tuesday in Washington. “The (Navajo) president and I have been talking to our elders, saying we need to talk about the Longest Walk from our own perspective. Today there are over 350,000 Navajos a century later. We need to reinforce to the younger generation that life is awesome. We need to inspire them to never give up on their goals in life, because our ancestors carried resilience all the way to their return home.”

Before the end of the installation ceremony, Elmer Begay, a staff member of the Navajo Nation Office of the President and Vice President, sang a protection song for the treaty’s exhibition.

Alongside the treaty, the museum has installed a Navajo loom and weaving on loan from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Juanita (Asdzáá Tł’ogi), the wife of Navajo leader Manuelito (Hastiin Ch’il Haajiní), brought the loom and weaving to Washington, D.C., in 1874, when she and Manuelito were members of a Navajo delegation meeting with the U.S. government.

Both the Navajo Treaty of 1868 and the loom and weaving can be viewed through early May on the 4th level of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington in the exhibition Nation to Nation. People can also see the complete treaty and transcript on the museum's website. Located on the National Mall at Fourth Street and Independence Avenue S.W., the museum is open each day from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. (closed Dec. 25). To learn more about programs and events at the museum, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, or visit AmericanIndian.si.edu.