NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

Carlos Martinez, Patriot and Philanthropist

The Defense Department discriminated against Latino veterans — Carlos Martinez decided to do something about it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fd/87/fd87d443-095c-4e2d-a36f-e12eb82f239e/gi_forum_detail.png)

When he reflected later in life on why, as a young man, he chose to enlist during wartime, Carlos Martinez said that avoiding service was never an option, not for his community and not for himself. In the mid-1960s, the United States had begun fighting the Soviet-supported North Vietnamese as part of its Cold War policy of containing Communism. Martinez was a young man working in the upholstery trade. He had gone into that line of work following the advice of his father, who “was a big proponent of getting a skill of some sort.” But it turned out he was allergic to the textile dust and, with the country at war, his path was clear. He had grown up in San Antonio, Texas, in a community where military service was common, respected, and valued because it seemed to promise the full citizenship that Mexican Americans like him had been denied. The expectation in his West Side neighborhood—similar to the experience in other under-resourced communities—was that you went into the military. There were, in his words, “no exemptions to be had.” The only choice Martinez had, thanks to his strong scores on tests, was what branch to join. “[F]ollowing [his] dad’s advice,” he opted for the branch where he could “get a better trade . . . than upholstery.” Learning aircraft maintenance was attractive, and so in 1966, Martinez joined the U.S. Air Force. Rather than the career in upholstery he’d envisioned as a high school student, advocating and caring for veterans became his life’s work.

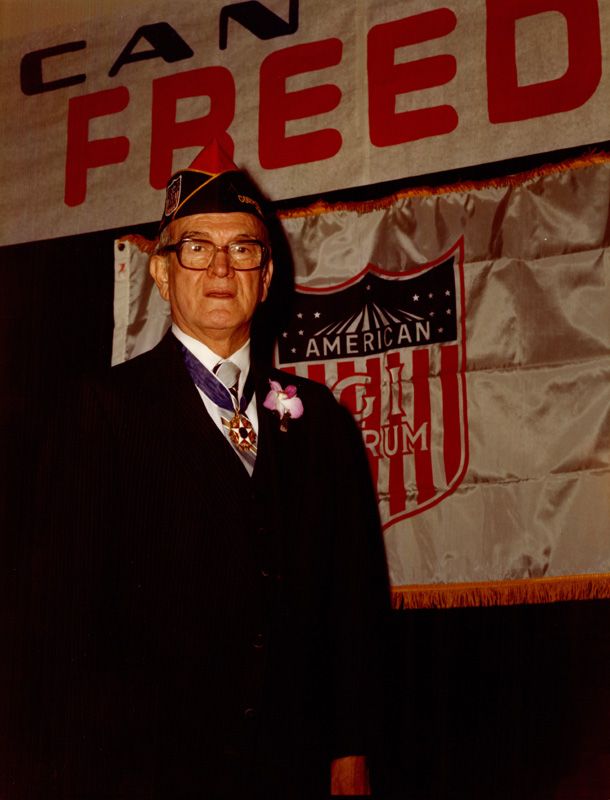

Martinez’s initial experience supporting fellow veterans came not long after leaving the air force when he and other Latino veterans found themselves facing employment discrimination due to their background. Kelly Air Force Base hired Martinez as a temporary worker for a civilian position and, initially, he was pleased. Soon he discovered that he and other Latino veterans had not been given the chance to apply for regular positions but had been limited to temporary jobs. Moreover, the men were not being given the training opportunities for advancement they were supposed to receive. Martinez had already experienced similar discrimination in the air force. Although Defense Department policy and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited racial discrimination, Martinez was not given a promotion he was eligible for while in the air force, and he had noticed then that other Latinos were in the same situation. At that point, he’d spoken with a superior about his concerns, but little was done. This time, Martinez took action. To challenge the unjust treatment at Kelly Air Force Base, Martinez and several others created an informal group they called Veterans for Equal Rights. The group brought public attention to the issue with support from important allies including the American GI Forum, a Latino veterans and civil rights group founded in response to discrimination faced by Mexican American veterans in World War II. In time, Veterans for Equal Rights won their fight and the affected veterans were hired into career positions.

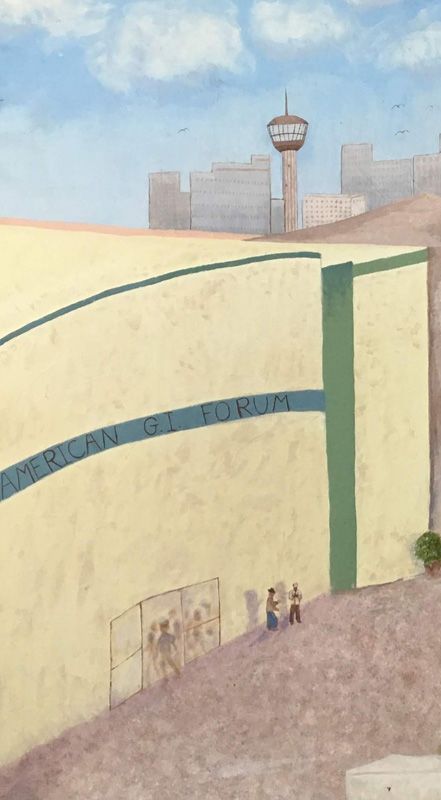

Impressed with the American GI Forum, Martinez joined the group and wound up building its modest program into a nationally recognized nonprofit. In the early 1970s, when Martinez began working with the American GI Forum’s Veterans Outreach Program as an outreach worker, opposition to the Vietnam War was strong. It was also the civil rights era, with the Chicano Movement fighting for Mexican American rights. Vietnam veterans, as Martinez recalled, “were not being well treated and received back from the war.” Leaders of the American GI Forum remembered that after World War II, returning servicemembers from Latino communities—communities with high rates of military service—had not been welcomed back as “equal citizens” and so they determined to do something about it. Within a few years, Martinez was executive director of the National Veterans Outreach Program (NVOP). Initially, the group had planned to focus on Latino veterans. But soon, Martinez remembered, “our doors were full, not from Latino veterans only.” In response, the NVOP opened its services to Vietnam-era veterans of all backgrounds. More recently, its clients have included veterans of U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In its early years, the NVOP focused on providing veterans with job training and assistance with finding employment. As homelessness among veterans rose in the early 2000s, the NVOP established a transitional housing program, opening the Residential Center for Veterans in San Antonio in 2005. It’s also added mental health services, with Martinez noting, “we continue to evolve, and we try to respond to the needs.”

Love of country defines patriotism, while recognizing and supporting the humanity of others is the essence of philanthropy. Martinez embodied both ideals. He served the country by joining the military and by challenging the discrimination he found there. He continued serving by building an organization helping veterans in need and without regard to their background. In August 2020, the nation lost a patriot and a philanthropist when Carlos Martinez, along with his wife Rita, died of COVID-19.

This blog post is based on an oral history with Carlos Martinez conducted by Amanda B. Moniz and Laura Lee Oviedo in January 2020 as part of the War and Latina/o Philanthropy Collecting Initiative.

This post was originally published on the National Museum of American History's blog on November 10, 2020. Read the original version here.