Young Eyes on Calcutta

Zana Briski and collaborator Ross Kauffman’s Academy Award winning documentary chronicals the resilience of children in a Calcutta red-light district

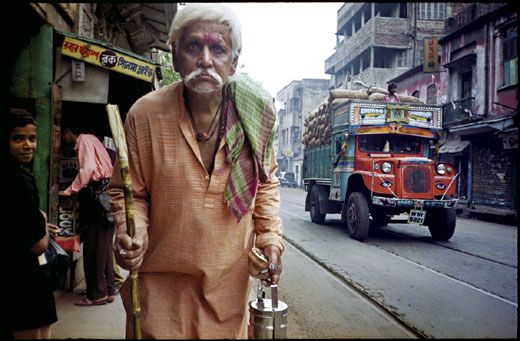

On a trip to Calcutta in 1997, Zana Briski visited the Sonagachi neighborhood, the oldest and largest red-light district in Calcutta. She was intrigued by its warren of brothels and other illegal businesses. Over the next two years the British-born photojournalist kept going back to get closer to the prostitutes and brothel owners whose lives she hoped to document. "Photography there is completely taboo," says Briski, 38, who now lives in New York City. "People there don't usually see Westerners, let alone people with cameras." She spent countless hours with the women, ultimately even convincing one brothel owner to rent her a room. "The women trusted me," she says.

As Briski worked, she was surprised that children—most of them sons and daughters of prostitutes—would surround her, fascinated by her camera. So she started teaching them to take pictures, setting up weekly classes and giving them cheap, point-and-shoot cameras with which to experiment. Their snapshots—arresting portraits of their families, each other and the surrounding streets—capture a chaotic world as few outsiders could.

Briski pressed on, securing grants to fund her efforts, soon dubbed Kids with Cameras, and arranging to sell the kids' photographs in Calcutta and New York City galleries. The pictures attracted attention. "These children have what adults most often don't: total openness," says Robert Pledge, co-founder of the Contact Press Images agency. Briski persuaded Pledge to meet the children, and he was soon convinced that the pictures had genuine merit. "Most photography is observation, from the outside," he says. "You're very rarely inside, looking from the inside out."

But teaching photography wasn't enough. Briski plunged full time into trying to help several of the kids get into private schools—all the while videotaping her efforts and their struggles. For two years beginning in 2002, Briski and New York-based filmmaker Ross Kauffman shot 170 hours of video of the children. Just walking through Sonagachi with a camera invited trouble, Kauffman says. "It was always a very tenuous situation. We had to be careful of when and how and who we were shooting. A fight could explode at any time because of the cameras, because of anything."

This past February, the resulting documentary, Born into Brothels, added an Academy Award for Best documentary feature to its more than 20 other awards, including the Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival. New York Times critic A. O. Scott called the 85-minute film "moving, charming and sad, a tribute...to the irrepressible creative spirits of the children themselves."

Briski and Kauffman, to preserve the subjects' anonymity, have chosen not to screen the film in India, though aid workers in Calcutta say that the children's identities are no secret; their names have been widely reported in the Indian press and the kids have appeared on Indian television. Critics there complain that Briski didn't sufficiently credit aid workers who helped her, and that her approach—taking the children out of their brothel homes and placing them in boarding schools—was presumptuous.

To be sure, her movie documents that some of the kids she sponsored dropped out of school. But she remains committed to her original vision of educating the children, and plans to go back to Calcutta this spring, where she hopes to open a small school for children like those in the film, with a curriculum that will focus on arts and leadership. She also wants to expand Kids with Cameras to Haiti and Egypt.

For children in Sonagachi and other Indian brothels, the cycle of poverty and prostitution is difficult to break. According to India's National Human Rights Commission, hundreds of thousands of Indian women work as prostitutes; some Indian aid organizations place the estimate as high as 15.5 million. Almost half of them began working as children. "The numbers have gone up and the ages have gone down," says Ruchira Gupta, an Emmy-winning documentary filmmaker who in 1997 founded Calcutta-based Apne Aap Women Worldwide to help Indian prostitutes. Gupta says brothel owners and pimps often press young women to have babies, making them more financially dependent on the brothel. "When mothers die of AIDS or other diseases," Gupta adds, "their daughters are immediately brought in."

In Born into Brothels, Briski's star student is Avijit, whose self-portraits and street scenes so impressed Pledge that he arranges for the boy to visit the World Press Photo Children's Competition in Amsterdam. But when Avijit's mother is killed by a pimp, the pudgy 12-year-old drifts away, skips photography classes and stops taking pictures.

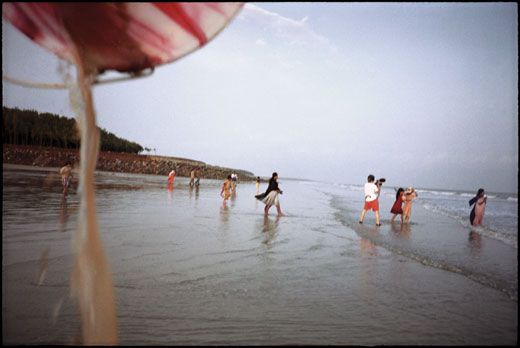

Briski, in a final effort to rescue the boy, finds Avijit and takes him to get a passport the day before he is to leave for Amsterdam. Avijit makes the journey from Sonagachi to Amsterdam, and to see him discussing photography with children from around the world in the exhibition's crowded halls is to see raw potential released. "Children at that age can so easily go in one or another direction," says Pledge. "That environment isn't specific to India, or to red-light districts. All kids have amazing learning abilities, and they're being robbed constantly in all parts of the world—sometimes not that far away."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)