Four Hundred Years Later, Scholars Still Debate Whether Shakespeare’s “Merchant of Venice” Is Anti-Semitic

Deconstructing what makes the Bard’s play so problematic

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/46/78468e8e-a7f2-4823-9608-97546dcf2168/sf37426.jpg)

The Merchant of Venice, with its celebrated and moving passages, remains one of Shakespeare’s most beautiful plays.

Depending on whom you ask, it also remains one of his most repulsive.

"One would have to be blind, deaf and dumb not to recognise that Shakespeare's grand, equivocal comedy The Merchant of Venice is nevertheless a profoundly anti-semitic work,” wrote literary critic Harold Bloom in his 1998 book Shakespeare and the Invention of the Human. In spite of his “Bardolatry,” Bloom admitted elsewhere that he’s pained to think the play has done “real harm … to the Jews for some four centuries now.”

Published in 1596, The Merchant of Venice tells the story of Shylock, a Jew, who lends money to Antonio on the condition that he get to cut off a pound of Antonio’s flesh if he defaults on the loan. Antonio borrows the money for his friend Bassanio, who needs it to court the wealthy Portia. When Antonio defaults, Portia, disguised as a man, defends him in court, and ultimately bests Shylock with hair-splitting logic: His oath entitles him to a pound of the Antonio’s flesh, she notes, but not his blood, making any attempt at collecting the fee without killing Antonio, a Christian, impossible. When Shylock realizes he’s been had, it’s too late: He is charged with conspiring against a Venetian citizen, and therefore his fortune is seized. The only way he can keep half his estate is by converting to Christianity.

It doesn’t take a literary genius like Bloom to spot the play’s anti-Jewish elements. Shylock plays the stereotypical greedy Jew, who is spat upon by his Christian enemies, and constantly insulted by them. His daughter runs away with a Christian and abandons her Jewish heritage. After being outsmarted by the gentiles, Shylock is forced to convert to Christianity— at which point, he simply disappears from the play, never to be heard of again.

The fact that The Merchant of Venice was a favorite of Nazi Germany certainly lends credence to the charge of anti-Semitism. Between 1933 and 1939, there were more than 50 productions performed there. While certain elements of the play had to be changed to suit the Nazi agenda, “Hitler's willing directors rarely failed to exploit the anti-Semitic possibilities of the play,” writes Kevin Madigan, professor of Christian history at Harvard Divinity School. And theatergoers responded the way the Nazis intended. In one Berlin production, says Madigan, “the director planted extras in the audiences to shout and whistle when Shylock appeared, thus cuing the audience to do the same.”

To celebrate that Vienna had become Judenrein, “cleansed of Jews,” in 1943, a virulently anti-Semitic leader of the Nazi Youth, Baldur von Schirach, commissioned a performance. When Werner Krauss entered the stage as Shylock, the audience was noticeably repulsed, according to a newspaper account, which John Gross includes in his book Shylock: A Legend and Its Legacy. “With a crash and a weird train of shadows, something revoltingly alien and startlingly repulsive crawled across the stage.”

Of course, Shylock hasn’t always been played like a monster. There’s little argument that he was initially written as a comic figure, with Shakespeare’s original title being The Comical History of The Merchant of Venice. But interpretations began to shift in the 18th century. Nicholas Rowe, one of the first Shakespearean editors, wrote in 1709 that even though the play had up until that point been acted and received comedically, he was convinced it was “designed tragically by the author.” By the middle of that century, Shylock was being portrayed sympathetically, most notably by English stage actor Edmund Kean, who, as one critic put it, “was willing to see in Shylock what no one but Shakespeare had seen — the tragedy of a man.”

But just what exactly did Shakespeare see in the character? Was Shakespeare being anti-Semitic, or was he merely exploring anti-Semitism?

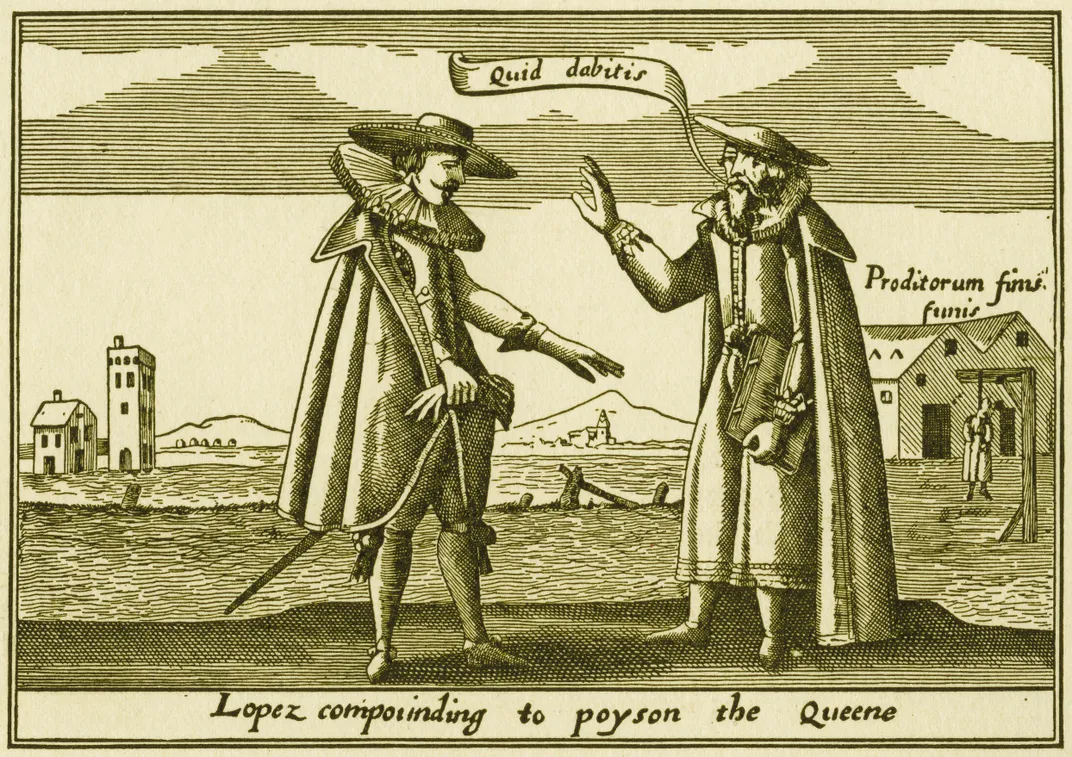

Susannah Heschel, professor of Jewish studies at Dartmouth College, says that critics have long debated what motivated Shakespeare to write this play. Perhaps Christopher Marlowe’s 1590 Jew of Malta, a popular play featuring a Jew seeking revenge against a Christian, had something to do with it. Or perhaps Shakespeare was inspired by the Lopez Affair in 1594, in which the Queen’s physician, who was of Jewish descent, was hanged for alleged treason. And of course, one has to bear in mind that because of the Jews’ expulsion from England in 1290, most of what Shakespeare knew about them was either hearsay or legend.

Regardless of his intentions, Heschel is sure of one thing: “If Shakespeare wanted to write something sympathetic to Jews, he would have done it more explicitly.”

According to Michele Osherow, professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and Resident Dramaturg at the Folger Theatre in Washington, D.C., many critics think sympathetic readings of Shylock are a post-Holocaust invention. For them, contemporary audiences only read Shylock sympathetically because reading him any other way, in light of the horrors of the Holocaust, would reflect poorly on the reader.

“[Harold] Bloom thinks that no one in Shakespeare's day would have felt sympathy for Shylock,” she says. “But I disagree.”

Defenders of Merchant, like Osherow, usually offer two compelling arguments: Shakespeare’s sympathetic treatment of Shylock, and his mockery of the Christian characters.

While Osherow admits that we don’t have access to Shakespeare’s intentions, she’s convinced that it’s no accident that the Jewish character is given the most humanizing speech in the play.

“Hath not a Jew eyes?” Shylock asks those who question his bloodlust.

Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that.

“Even if you hate Shylock,” says Osherow, “when he asks these questions, there’s a shift: you have an allegiance with him, and I don’t think you ever really recover from it.”

In these few humanizing lines, the curtain is pulled back on Shylock’s character. He might act the villain, but can he be blamed? As he explains to his Christian critics early in the play, “The villainy you teach me I will execute.” In other words, says Osherow, what he’s telling his Christian enemies is, “I’m going to mirror back to you what you really look like.”

Consider general Christian virtues, says Osherow, like showing mercy, or being generous, or loving one’s enemies. “The Christian characters do and do not uphold these principles in varying degrees,” she said. Antonio spits on Shylock, calls him a dog, and says he’d do it again if given the chance. Gratiano, Bassanio’s friend, isn’t content with Shylock losing his wealth, and wants him hanged in the end of the courtroom scene. Portia cannot tolerate the thought of marrying someone with a dark complexion.

“So ‘loving one’s enemies?’” asks Osherow. “Not so much.” The play’s Christian characters, even the ones often looked at as the story’s heroes, aren’t “walking the walk,” she says. “And that’s not subtle.”

The clearest example of the unchristian behavior of the play’s Christians comes during Portia’s famous “The quality of mercy” speech. Although she waxes eloquent about grace, let’s not forget, says Heschel, “the way she deceives Shylock is through revenge, and hair-splitting legalism.” She betrays her entire oration about showing people mercy when she fails to show Shylock mercy. Of course, Portia’s hypocrisy should come as no surprise — she announces it during her very first scene. “I can easier teach twenty what were good to be do than to be one of the twenty to follow mine own teaching,” she tells her maid, Nerissa.

As a result of Portia’s sermonizing about how grace resists compulsion, Shylock is forced to convert, clearly the play’s most problematic event. But Osherow thinks some of Shakespeare’s audiences, like contemporary audiences, would’ve understood that as such. “There was so much written about conversion in the early modern period that some churchgoers would have thought [Shakespeare’s Christians] were going about it in completely the wrong way.”

For example, according to A Demonstration To The Christians In Name, Without The Nature Of It: How They Hinder Conversion Of The Jews, a 1629 pamphlet by George Fox, conversion is not as simple as “bringing others to talk as you.” In other words, says Osherow, the forced conversion of Shylock “isn’t how it’s supposed to work according to early modern religious texts.”

Late American theatre critic Charles Marowitz, author of Recycling Shakespeare, noted the importance of this interpretation in the Los Angeles Times. “There is almost as much evil in the defending Christians as there is in the prosecuting Jew, and a verdict that relieves a moneylender of half his wealth and then forces him to convert to save his skin is not really a sterling example of Christian justice.”

Though it’s true that Shakespeare’s mockery (however blatant one finds it) of the play’s Christians doesn’t erase its prejudice, “it goes some way toward redressing the moral balance,” notes Marowitz. In other words, by making the Jew look a little less bad, and the Christians look a little less good, Shakespeare is leveling the moral playing field — which is perhaps what the play hints at when Portia, upon entering the courtroom, seems unable to tell the difference between the Christian and his opponent. “Which is the merchant here, and which the Jew?” she asks.

Now, with all of this in mind, is it accurate to label The Merchant of Venice an anti-Semitic play?

Heschel is correct to point out that Shakespeare isn’t championing Jewish rights (though it might be anachronistic of us to hold him culpable for failing to do so). But she’s also onto something when she suggests the play “opens the door for a questioning” of the entrenched anti-Semitism of his day.

“One thing I’ve always loved about this play is, it’s a constant struggle,” says Osherow. “It feels, on one hand, like it going to be be very conventional in terms of early modern attitudes toward Jews. But then Shakespeare subverts those conventions.”

Aaron Posner, playwright of District Merchants, the Folger’s upcoming adaptation of Merchant, also finds himself struggling to come to terms with the text.

“You can’t read Hath not a Jew eyes?, and not believe Shakespeare was humanizing Shylock and engaging with his humanity. But if you read [the play] as Shakespeare wrote it, he also had no problem making Shylock an object of ridicule.”

“Shakespeare is not interested in having people be consistent,” says Posner.

Like any good playwright, Shakespeare defies us to read his script as anything resembling an after-school special — simple, quick readings and hasty conclusions just won’t do for the Bard.

For District Merchants, Posner has reimagined Shakespeare’s script as being set among Jews and Blacks in a post-Civil War Washington, D.C. In a way, he says, the adaptation reframes the original racism question, because it’s now about two different underclasses — not an overclass and an underclass.

“It was an interesting exercise to take issues raised in Merchant of Venice, and see if they could speak to issues that are part of American history,” he says.

Posner sees it as his prerogative to engage with the moral issues of the play “with integrity and compassion.” Part of that means approaching the play without having his mind made up about some of these tough questions. “If I knew what the conclusion was, I’d be writing essays not plays. I don’t have conclusions or lessons or ‘therefores.’”

Four hundred years after his death, and we’re still confused by the ethical ambiguities of Shakespeare’s plays. That doesn’t mean we stop reading the difficult ones. If anything, it means we study them more intently.

“I think it is absolute idiocy for people to say [of Merchant], ‘It’s Anti-Jewish’ and therefore they don’t want to study it,” says Heschel. “It’s a treason to Western Civilization. You might as well go live on the moon.”

Despite its negativity towards Judaism, Heschel thinks Merchant is one of the most important pieces of literature from Western Civilization. “What’s important about is to read the play — as I do — in a more complex way, to see whether we are able to read against the grain. That’s important for all of us.”

Perhaps, on one level, Merchant is a play about interpretation.

“Remember Portia’s caskets,” says Osherow, referring to one of the play’s subplots, which has Portia’s would-be suitors try to win her hand by correctly choosing a casket pre-selected by her father. Those quick to be wooed by the silver and gold caskets are disappointed to learn they’ve made the wrong choice. The lead casket is in fact the correct one.

The lesson? “Things are not always what they seem,” says Osherow.

Indeed, a Jewish villain turns out to deserve our sympathy. His Christian opponents turn out to deserve our skepticism. And the play which tells their story turns out to be more complicated than we originally assumed.