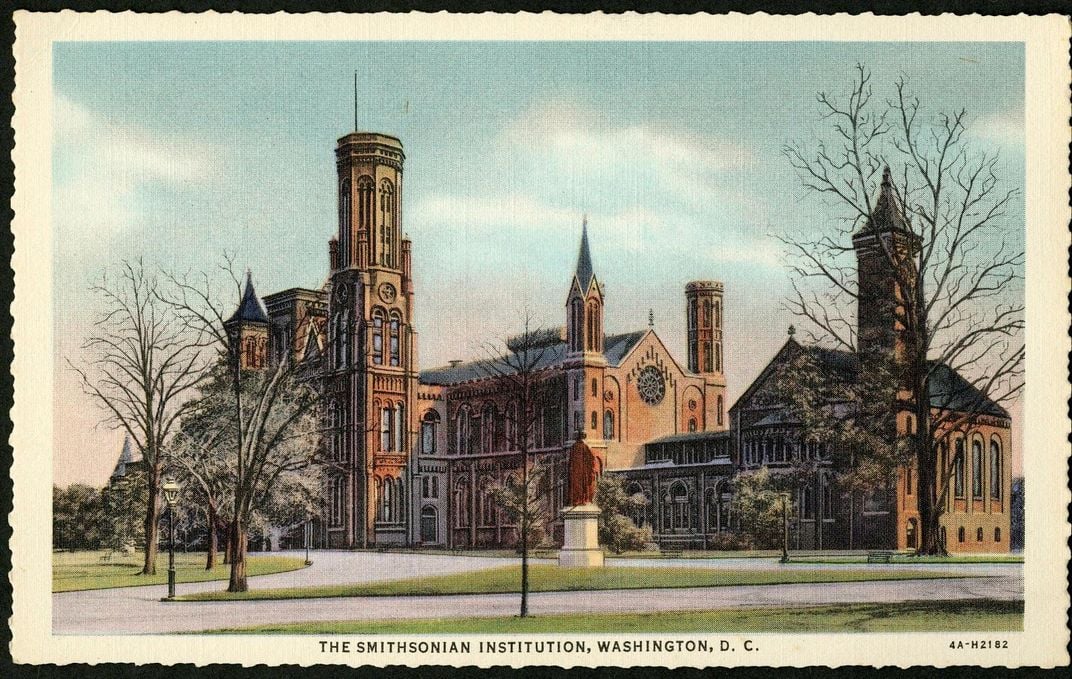

The Smithsonian Institution has been a part of the American landscape since 1846. Yet perhaps because of the breadth and eclecticism of its collections, visitors sometimes arrive at the Institution with a few misconceptions. So on the occasion of the Smithsonian's anniversary, we take this opportunity to clear up a few of the tall tales, myths and misunderstandings.

Myth #1: The Hope Diamond is cursed

Fact: It isn’t. A coincidental string of unfortunate events befell its handlers.

Backstory: The so-called curse originated as a marketing ploy devised by jeweler Pierre Cartier to entice Washington, D.C. socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean to buy the gem. Cartier created a fantastic story about the jewel’s provenance and how the stone brought grief to anyone who handled it. McLean purchased the jewel—an acquisition reported in the New York Times on January 29, 1911, with a recounting of Cartier’s dark tale. Over the years, other publications picked up the story, helping perpetuate the legend about the stone. McLean’s later misfortunes—her husband ran off with another woman and later died in a sanitarium, a car struck and killed her son and her daughter died of a drug overdose—contributed to the perception that the stone was cursed. After McLean’s death, the diamond came into the possession of jeweler Harry Winston, who later donated it to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, in 1958. The jewel was sent to the museum by registered mail and delivered by postal worker James Todd, who suffered several misfortunes the following year—a broken leg, the deaths of both his wife and dog and the loss of his house in a fire. Todd took it in stride. “If the hex is supposed to affect the owners,” he said, “then the public should be having the bad luck [not me]!” While the Smithsonian was pleased to receive the jewel—the centerpiece of its mineral collections—the public was less enthusiastic. “If the Smithsonian accepts the diamond,” one person wrote, “the whole country will suffer.” Museum curators, however, dismiss the idea of the stone bringing bad luck. The Hope Diamond has attracted millions of visitors to the Smithsonian over the past 50 years.

Myth #2: Smithsonian went in search of Noah’s Ark at Mount Ararat

Fact: The Smithsonian has never conducted archaeological work on Mount Ararat; in fact, no one knows whether the mountain is indeed the site of Noah’s Ark.

Backstory: According to the Book of Genesis, after the flood, Noah’s Ark came to rest on the mountains of Ararat. This description has led many people to focus their search for the Ark on modern-day Mount Ararat (also known as Mount Masis and Agri Dagi), in Turkey. Furthermore, aerial photographs of the site reveal a strange formation, known as the Ararat Anomaly, which some speculate is the Ark.

Myth #3: Antiquities department turned down a so-called prehistoric artifact

Fact: The Smithsonian does not have an antiquities department.

Backstory: In the mid-1990s, a creative graduate student crafted a letter under the name Harvey Rowe, curator of antiquities, rejecting the claims of an amateur paleontologist who was convinced he had discovered signs of prehistoric life in his own backyard: a Malibu Barbie doll. (A version of the letter appears at here.) The letter began circulating on the Internet in 1994 and quickly spread, tickling funny bones all over cyberspace.

Myth #4: The Smithsonian discovered Egyptian ruins in the Grand Canyon

Fact: It didn’t.

Backstory: On April 5, 1909, the Arizona Gazette ran the following headline: “Explorations in Grand Canyon; Mysteries of Immense Rich Cavern Being Brought to Light; Jordan Is Enthused; Remarkable Find Indicates Ancient People Migrated from Orient.” The article includes testimony of one G. E. Kincaid who says that he, traveling solo down the Green and Colorado Rivers, discovered proof of an ancient civilization—possibly of Egyptian origin. The story also asserts that a Smithsonian archaeologist named S. A. Jordan returned with Kincaid to investigate the site. However, the Arizona Gazette appears to have been the only newspaper ever to have published the story. No records can confirm the existence of either Kincaid or Jordan.

Myth #5: Betsy Ross stitched the Star-Spangled Banner

Fact: Mary Pickersgill stitched the flag that inspired the National Anthem.

Backstory: The making of the first standard of the United States is popularly attributed to Betsy Ross, a professional flagmaker who has become a national folk hero. The legend stems from Ross’ grandson, William J. Canby, who, in 1870, wrote down a story a relative had told him in 1857—well after Ross’ death. The account goes that in spring 1776, George Washington approached Ross with a rough sketch of a flag and asked her to make a national standard. With the United States preparing to celebrate its 100th anniversary, the story about the birth of the national flag captured imaginations. There is, however, no documentation that links Ross with making the first flag, and the events described in Canby’s account take place a year before the passage of the Flag Act—the legislation that dictates the style and substance of the national flag. Visitors to the National Museum of American History sometimes ask if the Star Spangled Banner—currently on display after extensive conservation efforts—is an example of Ross’s work. That flag was stitched by Mary Pickersgill and flew over Fort McHenry during the 1814 Battle of Baltimore, inspiring Francis Scott Key to pen the poem that became our National Anthem.

Myth #6: The Smithsonian Castle is haunted

Fact: The only souls that haunt the Castle are tourists searching for food and information.

Backstory: Tales of otherworldly inhabitants stalking the Smithsonian’s hallowed halls have been floating around for over a century. The Institution’s founder, James Smithson, is said to be among these otherworldly visitors. Another rumored ethereal presence is paleontologist Fielding B. Meek, who lived in pitifully small rooms in the Castle with his cat. His first residence was under one of the Castle’s staircases before an 1865 fire forced him to move to one of the towers, where he died in 1876. “Many ghost stories have swirled about,” says the curator of the Castle collection Richard Stamm, “but in the many years I have been in this building, no ghosts have ever shown their faces to me!”

Myth #7: Smithsonian owns something that once belonged to John Dillinger

Fact: The Smithsonian does not own any personal effects of John Dillinger.

Backstory: According to some, a morgue photograph of the sheet-shrouded corpse of John Dillinger suggests nature was rather generous to the gangster. Newspaper editors fearing scandal prudently refused to run the image. However, a popular rumor arose asserting that the gangster’s organ was in the collections of the Smithsonian. This myth has proved so pervasive that the Smithsonian has created a form letter to respond to curious minds: “In response to your recent query, we can assure you that anatomical specimens of John Dillinger are not, and never have been, in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution.”

Myth #8: There is an archive center underneath the National Mall

Fact: The Smithsonian’s storage facilities are mostly located in Suitland, Maryland.

Backstory: The notion that a labyrinthine network of storage space exists beneath the Smithsonian museums, under the National Mall, may have started with Gore Vidal’s novel The Smithsonian Institution and was most recently popularized by the movie Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian. Unfortunately, no such storage facility is to be found. The archive center depicted in the film is based on the Smithsonian’s storage facilities in Suitland, Maryland. However, there is a staff-only accessible underground complex of passageways that connect the Freer, the Sackler, the Castle, the African Art Museum, the International Gallery and the Arts and Industries Building.

There is also a tunnel that connects the Castle with the Museum of Natural History. Built in 1909, it is technically large enough to walk through; however, a person has to contend with cramped spaces, rats and roaches. A quick jaunt across the National Mall is the preferred means of traveling between the two museums.

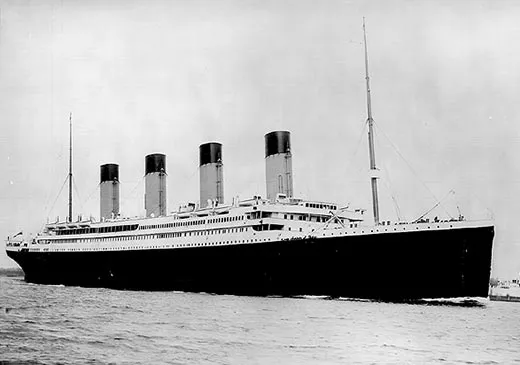

Myth #9: The Smithsonian owns a steam engine that was lost on the Titanic

Fact: While the museums cannot confirm this story, one thing is certain: the Smithsonian will not acquire or display artifacts culled from the Titanic wreck site.

Backstory: Inventor Hiram Maxim—who developed technological wonders such as the machine gun and the mousetrap—supposedly donated a steam engine used in a failed flying machine to the Smithsonian. The equipment was allegedly shipped from Britain to the United States aboard the ill-fated RMS Titanic. However, the ship’s cargo list—published in the New York Times in conjunction with the liability hearings that followed from the disaster—does not include any records of shipments made by Hiram Maxim. The Times article does state that “The cargo consisted of high-class freight, which had to be taken quickly on board and which could be just as quickly discharged.” Specifically listed are articles such as fancy foodstuffs and spirits, but it seems possible that a last crate of machinery could have been loaded on board.

Abiding by the sanctuary principle, the Smithsonian honors the site as a memorial to those who perished and will not disturb the remains of the disaster. While Titanic artifacts—such as articles of mail—have been on view at the Smithsonian, they were pieces retrieved from the surface of the North Atlantic.

Myth #10: James Smithson’s remains are housed in the Castle's sarcophagus

Fact: His body resides in the Tennessee marble pedestal beneath the sarcophagus.

Backstory: James Smithson, British scientist and founder of the Smithsonian who never set foot on American soil, died during a trip to Genoa, Italy. His remains were initially interred in the San Beningo cemetery, his gravesite marked with an elaborate sarcophagus (the one on view in the Castle). In 1904, the cemetery was going to be lost due to the enlargement of a nearby quarry, so the Smithsonian Board of Regents decided to collect Smithson’s remains and bring them to the United States.

Smithson was last disinterred in 1973. James Goode, former curator of Castle Collections, said it was because of ghost sightings. Officially, however, the reasons were more scientific: to mount a complete study of the coffin and the skeleton itself. Also, it was thought that documents about his life might have been buried with him. No written material was found with the remains, but a copy of the examination of the bones by the Smithsonian’s physical anthropologist Larry Angel (1962-1982) was filed inside the coffin before it was sealed and returned to the crypt.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/23/6b23bac3-2fdf-4770-850d-ae6c10440d27/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/44/d0/44d08fb6-5372-4387-865b-98d29b30ca5a/social-media-dimensions.jpg)