Tom Swift Turns 100

Tom Swift is turning 100—and he still doesn’t look a day over 18

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Tom-Swift-and-his-Motorcycle-631.jpg)

That’s just one more marvel from the fictitious boy inventor, who modestly but quickly took on ventures ambitious enough to entertain generations of readers. Along the way, he inspired more than a few actual innovators, such as Apple Computer co-founder Steve Wozniak and Jack Cover, who developed the Taser.

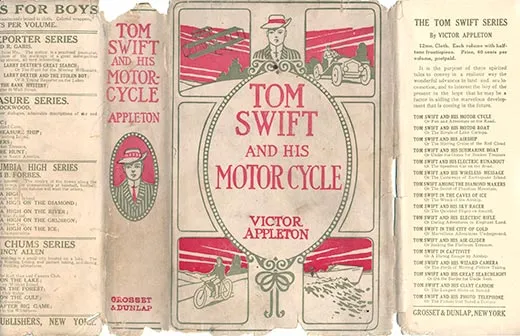

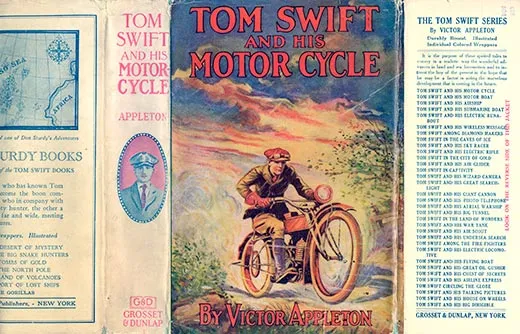

On July 1, 1910, the Library of Congress issued the copyright for the first Swift book, Tom Swift and His Motorcycle. Dozens of books followed in the first series, and four more series followed. In all there have been more than 100 books, with Tom passing the torch to Tom Jr. in 1954.

“I don’t pretend that they are great literature,” said James Keeline, a Tom Swift scholar and the organizer of the Tom Swift 100th Anniversary Convention, to be held July 16-18 in San Diego. “They are simply fun to read.”

Like many inventors, Tom started small: in the inaugural book, he merely modified his motorcycle. But soon he developed a “photo telephone” that predated the fax machine, a giant magnet to rescue a stranded submarine and a “house on wheels” that anticipated the modern motor home.

John Dizer, author of two guides to the Tom Swift phenomenon, summed up the books’ early appeal: “If Tom could invent something, so could we. With honesty and hard work, we could harvest the reward for our inventions. We might even become rich. Tom did.”

The Swift books “totally had me in that science/sci-fi inventor thinking from an early age, along with many friends,” Wozniak said in an e-mail. “When I had my own child, I found and bought some Tom Swift Jr. books, and they became among his favorites, too. He now works for NASA.”

And when it came time for Cover, who died last year at the age of 88, to name his invention of an electric gun that can temporarily immobilize people, he chose “Taser”—from an acronym for the Thomas Swift Electric Rifle, a Swift creation similar to Cover’s device.

Charles Campbell, a professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering at the University of Southern California, said the Tom Swift Jr. stories provided formative reading in his youth. “My father was an art curator, and my mother was a social worker. Neither side of the family has a scientist in it as far as anyone knows,” Campbell recalled. “I credit my interest in science to growing up in the early days of the space race and to the Tom Swift Jr. stories.”

Victor Appleton, the original Swift author, and Victor Appleton II, his successor in the second Swift series, would surely find such praise gratifying—if they actually existed. But they were pseudonyms for a stable of writers who churned out the Swift stories over the years, most of them for the now-defunct Stratemeyer Literary Syndicate, a kind of factory for children’s serials founded by Edward Stratemeyer in 1905.

“It is the purpose of these spirited tales to convey in a realistic way the wonderful advances in land and sea locomotion and to interest the boy of the present in the hope that he may be a factor in aiding the marvelous development that is coming in the future,” readers of the dust jacket on the first Tom Swift book were told.

One of the hallmarks of the early Swift books is the way they reflect the times in which they were written. The first series, for example, revisits a world in which the Wright brothers’ inaugural flight is still fresh in memory, but it also includes a character, casually described as a “darky,” who works as Tom’s servant.

“We should note the period in which the writing was done and the audience for whom the writing was intended,” Dizer wrote in explaining such offensive characters.

The second series, launched in 1954, embraced the era’s fascination with outer space and tackled Cold War espionage themes, with fictional Brungarians occasionally standing in for the Soviets. In Tom Swift and His Rocket Ship, the young inventor beat real-life space explorers into orbit by seven years. The Eisenhower-era Tom Swift books also welcomed nuclear energy with unblinking optimism; one story line connected sabotage with “some crank who is opposed to atomic progress and wants us all back in the Stone Age.”

Simon & Schuster, which purchased the Stratemeyer Syndicate in the 1980s, introduced the latest Tom Swift series (“Tom Swift, Young Inventor”) in 2006, and the most recent book (Tom Swift: Under the Radar) appeared in 2007. The stories seem generally more domesticated than their predecessors, told in the first-person voice of teen confessional.

Although there are no immediate plans for new Tom Swift books, Simon & Schuster has given the latest titles the most modern of treatments, releasing them as e-books—an innovation Tom Swift would surely love.

Danny Heitman, a columnist for the Baton Rouge Advocate, is the author of A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.