The Woman Who Brought Van Gogh to the World

Art lovers have Vincent van Gogh’s sister-in-law to credit for introducing the impressionist’s work to the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Vincent-van-Gogh-Doctor-Gachet-631.jpg)

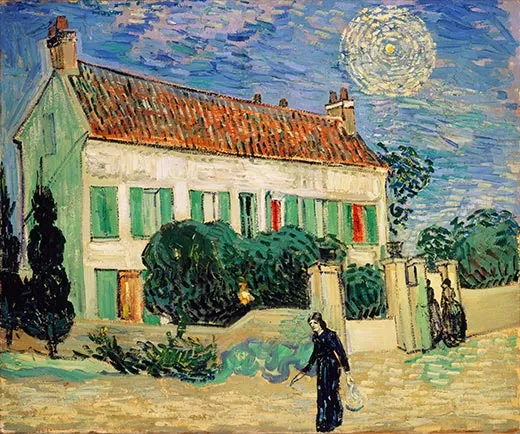

When Vincent van Gogh tragically killed himself in 1890, many of the works that would later gain him posthumous fame and fortune were barely dry. In the last ten weeks of his life, which he spent in Auvers-sur-Oise, France, Van Gogh experienced a period of unprecedented productivity, often painting an entire canvas in a day. Van Gogh in Auvers: His Last Days, a new book written by Wouter van der Veen and Peter Knapp, compiles the paintings Van Gogh produced during that time, interspersed with correspondence and information about the artist later in his life.

While other artists in Van Gogh’s social circle admired his work, most of the public had no knowledge of him until years after his death. When he died, Van Gogh left behind his brother Theodore (called Theo) and Theodore’s wife, Johanna. Theo died just two months after his brother. It was Johanna, the mother of a new baby boy named Vincent, who took it upon herself to introduce Van Gogh’s paintings to the world. I spoke with Wouter van der Veen about the last section of his book, a look at the life of Johanna van Gogh.

Tell me about Johanna’s life before the Van Goghs.

There’s not much known about her life before. She was the perfect spouse, and it was like she was bred for that. For a guy like Theo, who was a well-known art dealer, of course for him it was important to marry a wife who was well educated; not well educated in the sense that she would know so many things, but in the sense that she was well instructed, she had good manners and she would know how to do the household and how to keep everything tidy. Of course there was love between the two, but she was a girl who was getting prepared throughout her life to find a good husband.

She’s an unlikely figure to play this part in art history. In the whole research process, I wanted to find out who Johanna really was, and I couldn’t find her, she just wasn’t there. It’s as if she only starts to exist when the facts in her life put her in the position to make the right decisions and force her to blossom. And what comes out of this person is amazing, and the lessons she teaches us are incredible. She did better than all the guys around her could have ever dreamed.

Why did Van Gogh and his art become her cause?

First of all, I don’t really think she had a choice. She had all this art, and of course, Theo told her about it and it was part of her life. She had no choice but to go on with that. She had an amazing amount of art, and there were ongoing projects that Theo left behind. He wanted to organize an exhibition of Vincent’s works, and he wanted to publish the letters. He couldn’t do either of these because he died.

Johanna came from a wealthy family from Amsterdam, a family that was connected with the artists and the avant-garde there. So when she ended up being a widow, she was naturally in contact with all these people, who wanted to comfort her and who wanted to explain to her what she had, and what she should do. To start with, she listened and obeyed, like she was used to. Afterwards, that’s when she really starts to become an art dealer, because she is also not only doing this for the memory of her late husband, but also for the growing little Vincent, her son. And she wants to make his future secure, so she is trying to make a lot of money. She knows what Theo told her, never ever sell [the collection] piece by piece to whoever wants to give you money for it. Always act like it is what it is: very rare, very precious and very important art.

Was Van Gogh already fairly established in certain circles? How did Johanna and Theo know this art was so important?

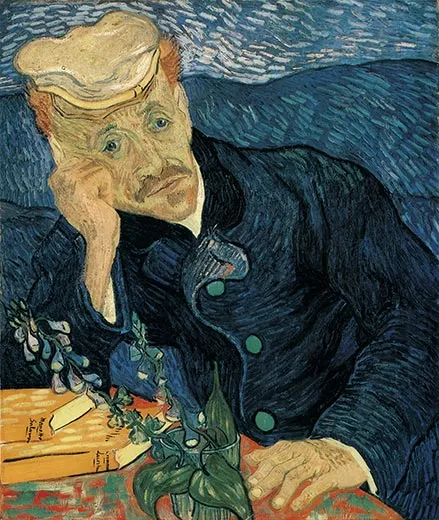

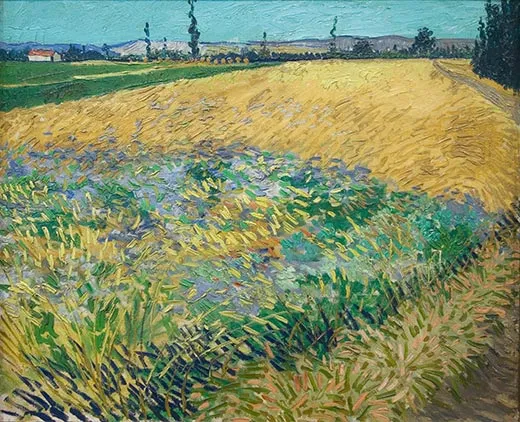

Yes. That’s one of the main new insights, not only in my book but also in the latest research over the last ten years. The people who had access to his work admired it. Today, this is the era of information and Internet and Facebook, but if an artist has amazing work today and he starts to show it around, it will take him about three to five years before he is known. That would be normal. In his time, the important works Van Gogh made, let’s say Sunflowers, [the portrait of] Doctor Gachet, Wheat Fields, weren’t even dry when he died. So even if he had the Internet, it still would have taken three years, but he didn’t, so it is absolutely normal that a guy with this kind of talent, and who makes these kinds of masterpieces, would go unknown for so long.

Of the people who saw what he made, there was only one who said, “This is the work of a lunatic,” who actually wrote about it. Even that says something, I mean, an important guy saying this is the work of a lunatic means it’s worth writing about. But other people and art critics and his peers, people like Monet, people like Gauguin, who were not unknown or unimportant even then, said this guy is a genius. And of course, Theo knew about that because Theo was the art dealer who sold Gauguin and Pizarro, and those were the guys who admired the work by Vincent. So of course the family and Johanna knew that this was important work.

Were the paintings literally not dry when he died?

No. The sunflowers paintings were made in [18]88, so they were probably almost dry. But look at the thickness of the Van Gogh paintings. If you have ever tried to paint with oil paints, it takes an amazing time to dry. That’s why Van Gogh watched all his paintings constantly, and he stuck them in piles under his bed, and even when the canvases touched each other, even months after, when the paintings were finished, still from one canvas to another, the paint is transferred. It’s so thick it can really take a year or 18 months to dry.

Would you say that Johanna was perhaps the single most important figure, perhaps aside from the artist himself, who contributed to making Van Gogh a household name over a century later?

I’m absolutely confident; I really am 100 percent sure. I think the fact that she was a woman was actually an advantage, because nobody saw her coming. Like nowadays, the main issue is money, and when something smells like money, a lot of greedy people come and try to get a piece of it. But this innocent-looking young woman with a little baby on her arm, nobody took her seriously, so that kind of kept the collection together for a longer time than if Theo was still alive, I think. She was able, still in 1906, to show a complete set of Van Gogh works.

Is there anything you’d like to add?

The book started as a catalog of Van Gogh’s work in the last ten weeks of his life. And then we started to wonder, what happened with the works? I mean, it’s OK to have them lined up and that’s great, but what happened with them and who took the collection so far? We started to get interested in Johanna van Gogh, and the only person we met was “Jo.” The pictures we saw were always of this innocent young lady, and when we started digging we started to find pictures where you could see this woman, and even in her eyes, I would have loved to talk to her, because she inspires something very deep, very thoughtful, very smart, very clever. I hope I can contribute to the fact that people will remember her, this fantastic woman, as Johanna Bonger, and not “Jo van Gogh.” She really deserves her full name, her own name.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)