The Swimsuit Series, Part 5: Olympic Athletes, Posing

Vintage styles cycle in and out of favor among medal-winning racers

![]()

![]()

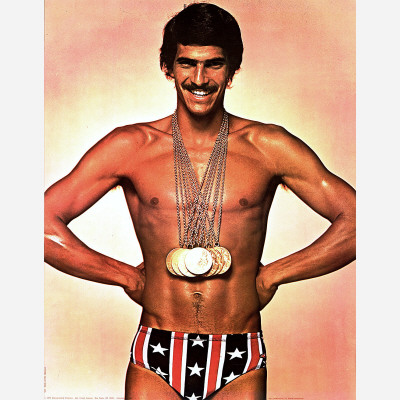

A few years before Farrah Fawcett donned her red bathing suit, seven-time gold medalist Mark Spitz wore his stars and stripes Speedo to dramatic effect in the 1972 Olympics in Munich. Tanned and toned in this photo, Spitz stands, arms akimbo, grinning and gilded with first-place medallions. If Fawcett was the 1970s manifestation of the All-American girl in her one-piece, Spitz was the male equivalent: virile and mustached, confident. (That ‘stache, incidentally, began as a form of rebellion against his swimming coach’s instructions and was going to be shaved off before the Olympics, but Spitz’s facial hair became such a part of his look that he always competed with what he referred to as his “good-luck piece.”)

While Speedos remain popular, competitive racing suits have evolved since the ’70s. They’ve become so technically advanced that the suits, and, in particular, Speedo’s full-body LZR Racer worn by the likes of Michael Phelps, were banned from competition in 2010. As Sarah Rich wrote on Design Decoded: “A suspicious number of record-breaking times were documented after competitors began wearing this gear, which includes drag-reducing polyurethane panels, buoyancy-enhancing material, and no seams—instead, the pieces are welded together ultrasonically.”

Before ultrasonic welding and mimicking sharkskin were part of the repertoire, what did U.S. swimmers of yore wear in the Olympics? Sure enough, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, has some answers!

Duke Paoa Kahinu Mokoe Hulikohola Kahanamoku is famous as the father of surfing, but the Hawaiian athlete took his swimming ability to the Olympics, where he first won the gold in 1912 in Stockholm. Kahanamoku went on to win medals during the 1920 Games in Antwerp and 1924 Games in Paris and competed again in 1932 on the U.S. water polo team.

Kahanamoku set swimming records, rescued drowning fishermen, appeared in films and brought surfing to the world with international exhibitions; he eventually became sheriff of Honolulu (where he remained in office for almost 30 years).

In this portrait from 1915, he stands proudly on a beach in front of a surfboard inscribed with his name, wearing a fetching one-piece. (The suit is likely made of wool, the board solid koa wood.)

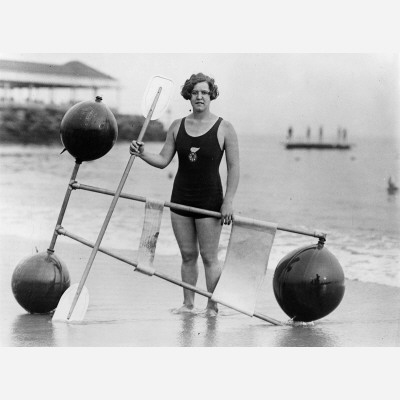

Gertrude Ederle, 1925. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, by Underwood & Underwood.

Then there’s Gertrude Ederle, 1924 gold and bronze medalist in swimming. Medals aside, she’s more well-known as the first woman to swim the English Channel. Annette Kellerman (who rather infamously wore one of the first skin-tight women’s one-piece bathing suits) attempted the 21-mile swim unsuccessfully on three occasions in 1905. But on August 6, 1926, Ederle set out at 7:08 a.m. and swam 14 hours 31 minutes to reach England’s Dover coast. With that time, she bested the five other Channel-crossing swimmers (all male) by an hour.

In this photograph, taken a year before crossing the Channel, we see Ederle standing on the beach holding an oar and some buoyant-looking contraption (Anyone know what it is?). Ederle’s wearing a suit emblazoned with what appears to be a chariot, and since her hair is done in 1920s-style pin curls, she certainly hadn’t just emerged from the water. (Not pictured here are the goggles she invented using leather and rubber, which are part of the Smithsonian’s collection.)

Also: Notice any similarities between her suit and the 2012 U.S. women’s swimming team suits?

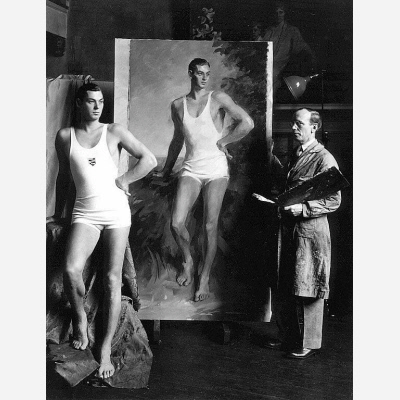

Johnny Weissmuller, 1924. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, by Pach Brothers Studio.

Keeping with 1924 medalists, we turn to Johnny Weissmuller. He finished the 1924 and 1928 Olympics with five gold medals and one bronze and was heralded as one of the greatest swimmers of the first half of the 20th century.

Even then, the swimmers’ build was a ticket to advertising; Weissmuller traded his suit for briefs when he became a model for underwear company BVD. And then he traded his underwear for a loincloth when he scored the role of Tarzan. He was in six Tarzan movies before he went on to play Jungle Jim, start a swimming pool company, launch the Swimming Hall of Fame, start the failed tourist attraction Tarzan’s Jungle, have his golf cart captured by Cuban rebels, and find his face on the cover of the Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Seen here in this portrait of a portrait, Weissmuller perches jauntily on a drop cloth wearing a white suit, a similar style to Ederle’s and Kahanamoku’s, and well, to current Speedos, it appears. Holding his palette, the painter stands by his work and gazes not at the camera but at his apathetic subject.

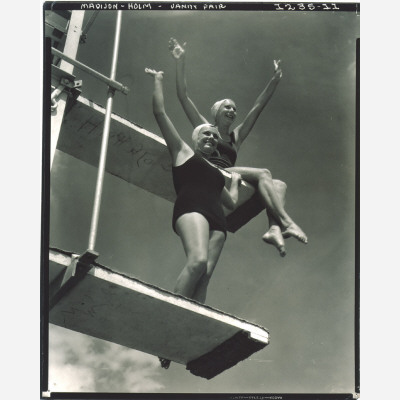

Eleanor Holm and Helene Madison, 1932. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution by Edward Jean Steichen

And finally, Olympic swimmers Eleanor Holm and Helene Madison: Madison swam competitively for only five years, but in that time, she won three gold medals in the 1932 Games. Holm, standing beside her, competed in the 1928 and 1932 Olympics. She was en route to the 1936 Games when she was dismissed from the U.S. swimming team for a “champagne-drinking incident.” What does an international incident involving champagne look like? Apparently, Holm helped turn the boat taking the U.S. swimming team to the Berlin Olympics into a booze cruise; she had too much to drink, was reported to the team captain and got booted from the team. Devastated, she watched from the stands as her teammates competed. Despite the scandal, Holm was able to follow in fellow swimming medalist Weissmuller’s bare footsteps when she took her place on the silver screen as Tarzan’s love interest in the 1938 Tarzan’s Revenge.

In this photo, taken at the 1932 Summer Games, teammates Holm and Madison pose together on diving boards, wearing the basic aquatic one-piece and swim caps, toes pointed, waving to an unknown crowd. Not the suits typical of the day, they’re similar in cut to today’s competitive gear. Aquatic fashion, it seems, has stepped back from the flashy 1970s and ’80s to take its cues from the modest 1920s.

All this makes me wonder what it must be like to devote your entire youth to training, competing and winning, and then wake up one day realizing it’s time to figure out what to do with the rest of your life. Do you teach the world to surf? Portray a jungle denizen? Drink a little too much bubbly? Become a real estate mogul? Now that Michael Phelps has retired at age 27 as the most decorated Olympian in history, what’s next for him, besides collecting millions in oh-so-boring endorsements? Maybe he should bring back tradition and consider swinging from vines wearing nothing but a loin cloth.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)