The Real Deal With the Hirshhorn Bubble

The Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum looks to expand in a bold new way

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hirshhorn-Museum-bubble-631.jpg)

UPDATE, June 5, 2013: The Smithsonian Institution announced today that it will not proceed with the "Bubble" project. For more details, read our latest post on Around the Mall.

UPDATE, May 23, 2013: The Hirshhorn board of trustees was unable to reach a decisive vote on the fate of the museum's bubble project. As a result, director Richard Koshalek resigned from his position, effective later this calendar year. For more details, read our post on Around the Mall.

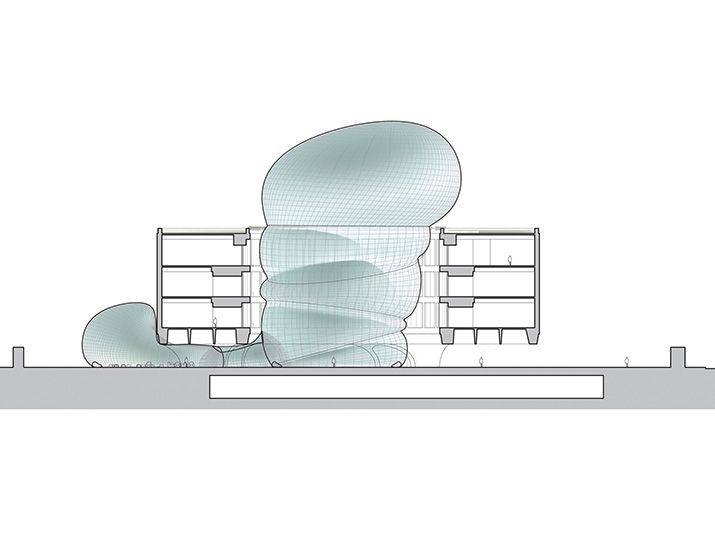

A little over three years ago, what looked like a droll New Yorker cartoon landed in the pages of the New York Times and the Washington Post. An architect’s rendering depicted a glowing, baby-blue balloon bulging up through the doughnut hole of the Hirshhorn Museum, with another smaller balloon squished out to the side, under the concrete building’s skirt. The design was described as a “seasonal inflatable structure” that would house pop-up think tanks about the arts around the world, transforming the nation’s contemporary art museum into a cultural Davos on the Mall.

The brainchild of Hirshhorn director Richard Koshalek and New York architects Diller, Scofidio + Renfro, the off-kilter dome, jaunty as a beret, represented an invasion of asymmetrical architecture—even asymmetrical thinking—into America’s most symmetrical city. If buildings define the institutions they house, the inflatable (commonly called the Bubble) promised to be a daring, innovative, puckish signal that bright, unconventional minds are crackling inside. “Thinking different,” it said.

But would the design fly in a strait-laced city like Washington—where other charismatic architectural ideas had been defeated before (notably Frank Gehry’s 1999 proposal for the Corcoran Gallery of Art)? “Washington is a city that needs a jolt,” says Koshalek, “but it has a long history of rejecting unusual projects. So the uproar for and against it didn’t land in the Big Surprise Department. But this is how museums are going to have to evolve in the future.”

Koshalek is, literally, a decorated veteran of many culture wars: The gray-haired, 71-year-old director can wear the chevalier of arts and letters pin from France’s Légion d’Honneur on the lapel of his deceptively conventional, pinstriped suit. Trained as an architect at the University of Minnesota, he is a former director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and former president of Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. “He’s a flame thrower in a gray suit,” says Thom Mayne, the Pritzker Prize-winning architect who collaborated with Koshalek on several projects in L.A. “There’s a certain complacency in that series of institutions [on the Mall], a long acquiescence to history. Richard wants to put history in contemporary terms, to play it forward through modern devices, through a modern lens.”

In the past three years, Koshalek and his team have been working through the engineering problems, studying target audiences and conceptualizing the programming. Though it’s too early to detail any specific events that could take place in the Bubble, Koshalek cites the “cultural diplomacy” of Daniel Barenboim, who brings together young Palestinian and Israeli musicians in his West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, and L.A. Philharmonic director Gustavo Dudamel, who has created orchestras for disadvantaged youth, to foster their skills and self-confidence. Artists of all disciplines, says Koshalek, can leverage their art for social purposes, and the programs should be driven by artists themselves.

But the biggest challenge remains the funding. The project attracted several large donors early on, and several members of the Hirshhorn’s board have stepped up to the plate. But fund-raising is now at a crucial point. The museum has set itself a May 31 deadline and, as this issue was going to press, Koshalek estimated that he was $5 million short of the $12.5 million goal. It’s crunch time at the Hirshhorn. “Unlike most major museums, because it’s the government, the Hirshhorn is woefully understaffed, with just one development person,” says Paul Schorr, the board treasurer. “The immediate issue is the money. We’ve got to get the funding to prove we can build, and the rest will fall into place, in my opinion.”

Leading cultural figures in America and around the world are watching intently to see if they can beat the deadline. “My sense of the Hirshhorn was that it was fixed, that it was not going anywhere other than where it already was,” says architect Gehry. “It’s refreshing to see an institution that has the optimism to see the world around it changing, and to experiment with ideas like this. Having a conference room for a think tank in an existing building would be OK, but in an exuberant, expressive space, that will get a lot more thinking in the tank.”

“The program is a great and important idea, especially in Washington,” says artist Barbara Kruger. “The visual arts are so marginalized in our country. There’s so little focus on their development and how they contribute to the possibilities of everyday life that’s different than the one we know. It’s an ambitious idea, but having this sort of site in the capital for an exchange and discussion of ideas on the arts is a very important thing to do.”

“I’ve worked with Richard in the past and he’s always brought people together in a way that’s fomented lively discussions on the arts,” says the sculptor Richard Serra. “There’s always a need for bringing people together to discuss the arts, and in America there’s a lack of support for doing that.”

“This is very much at the forefront of a trend today of temporary cultural spaces, which are very appropriate and cost saving—the Bubble would cost a fraction of the price of a new wing,” says Victoria Newhouse, an architectural historian whose most recent book, Site and Sound, raises the idea of alternative spaces. She predicts they will be a major new phenomenon. “The Bubble is innovative and fun, funky and smart, and it serves its purpose. One of the problems with ivory-tower institutions is that until recently they’ve divorced themselves from the real world, and it’s clear that today’s younger generation has rejected the formality of traditional public spaces. We’re in the process of revolutionary changes for museums, libraries and concert halls. The Bubble is completely in line with the new trend. I think Koshalek is a visionary.”

The stakes for Washington, D.C. itself are also high, according to Kriston Capps, the D.C.-based senior editor of Architect magazine, who initially criticized the proposal writing that “a splashy lecture hall will distract from the Hirshhorn’s central scholarly mission as a contemporary art museum.” He has since recanted: “My position has evolved. The National Mall is close to built up and something new is very exciting—and it [the Bubble] fits beautifully with the existing architecture.” But the significance of the project is even larger than its design. “Washington can’t afford the defeat of a relatively low-cost project like this. It would be a blow to other progressive projects here.” Conversely, its success could spur new architectural and cultural creations the city needs.

“The nature and form of the design is a direct response to the Hirshhorn itself and its ‘dome’ is a clever response to the Washington federal context and history,” says Kurt Andersen, novelist, host of public radio’s “Studio 360” and Time’s former architecture and design critic. “Buildings in Washington want to seem ancient and eternal; the Bubble means to look brand-new and be evanescent, seasonal. With the Bubble, Washington has a chance to prove that it has a sense of humor and an appreciation for poetry and the eccentric and fun. It’s an inexpensive way for Washington to say to America and the world that it’s grown-up and risk-taking enough to be a place that really believes in contemporary art specifically and innovation generally. If it happens, my reaction as a New Yorker will be envy. But as a citizen, it will be pride.”

***

Whether made out of soap or a high-tech membrane, bubbles are dynamic: They move. “Building the Bubble is not like pitching a normal tent, or even an inflatable structure over a tennis court,” says DS+R principal design architect Liz Diller, a boyish-looking 59-year-old who wears her cropped hair with an unruly cowlick erupting over her brow, off-center. The membrane is not just a roof over the hole in the doughnut but instead a continuous, single-surface membrane that bulges out of the top and bottom, forming a room within the courtyard of the existing museum, capturing an additional 12,000 square feet of space.

The museum hired German engineers who specialize in tensile structures to analyze the design. An increase in the wind outside, for example, would increase pressure inside, with structural consequences: The engineers had to stiffen the fabric to withstand fluctuations in air pressure. On computers, the engineers produced structural clouds that showed how much pressure the air would exert at any spot, revealing the stresses at every point in space.

“Even though the simplest, most efficient form is a sphere, the goal was to produce an asymmetrical structure, so we had to fight physics to find the right form,” says David Allin, a project leader for DS+R. And asymmetry was already built into the design of the museum by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, the original architect who created subtle, off-centered geometries in the courtyard of the otherwise circular building. At its core, the modernist Bunshaft design is not classical.

The engineers produced a tome of rigorous calculations, charts and diagrams, including beautiful computer sketches that show the Bubble girdled in several spots by cables that tether it invisibly in place, allowing movement within dimensional limits. The membrane never touches the drum, and hidden attachments to the support structure and to a ring inside the drum don’t show on the historic structure. “Fortunately the building is heavy and has excess capacity to take the load of the Bubble,” says Allin.

One of the most elusive tasks was finding a material that would be sufficiently flexible, durable and translucent. The Bubble had to be foldable and luminous. The architects worked through several options, starting with a resilient, translucent Teflon fabric, which did not prove strong enough, and then a silicon-coated glass fiber, which wasn’t resilient enough under folding, and then a polyvinyl chloride-coated polyester fabric typically used for tensile structures, which was not sufficiently translucent. Modifying the PVC technology, however, resulted in greater translucency, offering a solution that also stood up in computer-model stress tests for earthquakes and hurricane force winds.

The next challenge was figuring out the intricate choreography necessary to put the Bubble up and take it down. The architects’ sketches of the process recall detailed Renaissance drawings of obelisks being lifted onto barges in Egypt and then, after traveling thousands of miles, being hoisted onto pedestals in the plazas of Rome. The New York architects consulted with Swiss contractors who specialized in rigging gondolas for funiculars. “The prefabricated tent,” explains Diller, “comes off a truck as a continuous membrane to be unrolled and then hoisted up with mechanical winches, and dropped within the top rings and then inflated with a positive infusion of air from the building’s own air handling system. The flat membrane fills and then pops open on the outside into a dome.” Staging the erection will take a week, but inflating the balloon only a half-hour. The whole operation is virtually a performance piece, ending in the climactic moment when it all snaps into place.

***

In his many incarnations, Richard Koshalek has always pushed the institutions he has headed to move beyond the white walls of the gallery. In Los Angeles, he arranged guerrilla performances on loading docks. In Pasadena, he took part of the Art Center College program off its ivory tower suburban hill and planted it in the city’s urban grid, where it was accessible to public transportation.

At the Hirshhorn, Koshalek faced new challenges. New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable called the Hirshhorn a “bunker” when it opened in 1974, and 92-year- old Olga Hirshhorn, widow of the collection’s founder, Joseph H. Hirsh-horn, says that the museum had always struggled to find more space in its closed, three-story doughnut form.

Last year, Koshalek magically turned the institution inside out by commissioning multimedia artist Doug Aitkin to create a 360-degree film, Song 1, that was projected on the museum’s cylindrical exterior walls. The event extroverted the museum and activated public space outside—a little like a drive-in theater, only on the Mall. Later in the year, Koshalek invited word artist Barbara Kruger inside to appropriate the walls, ceilings and floor of the basement lobby, so that now people who visit the museum are entirely enveloped by her words and ideas.

Suddenly the distinguished but staid museum was alive, and even cool and contemporary. Attendance skyrocketed from 600,000 annual visitors to over a million. “Richard is opening the institution up,” says Gehry. “He’s living in his time, trying things, avoiding the tendency to head an aloof institution.”

Early in his tenure as Hirshhorn director, Koshalek met with Diller, Scofidio + Renfro at its offices in New York to discuss building an alternative “creative” space that would act like an open loft. He wanted to spark a dynamic relationship between audience and presenter, “an anti-auditorium” that could handle large crowds in shifting, democratic, multitasking configurations. Multiple screens would face in multiple directions, in the round. Digital technology would foster global reach.

At a meeting in late 2009, around a conference table in their offices, the architects, Koshalek and his Hirshhorn associate Erica Clark held a jam session about what form the anti-auditorium should take. A neat white Styrofoam model of the Hirshhorn was sitting on the conference table. The architects presented about 20 ideas, but at a certain point, Diller produced a clear plastic dry cleaner bag, passed it through the hole at the center of the model and started blowing into it. The plastic inflated into a dome. “That’s it!” exclaimed Koshalek, in a eureka moment.

“It was a beautiful way to develop architecture with a client,” says Allin. “No preconceptions, nothing set. We responded to him, and he to us.”

The concept didn’t come out of thin air. For architects, inflatable structures are a legacy dating from the 1960s and ’70s, when artists, architects and designers made inflatable cookbooks, furniture and environments. Concrete was seen as “establishment,” and inflatables, as countercultural. Diller and her partner Ricardo Scofidio were players in this milieu, having spent decades in New York’s downtown art bohemia blurring art and architecture, cultivating a conceptual approach to architecture rather than a formal one, causing people to think rather than just look. In their Blur Building for Swiss Expo 2002, for example, the architects built a misting structure permanently surrounded by a cloud. Early in his career, Scofidio had designed performance stages for rock bands, including Pink Floyd, out of scaffolds, creating extraordinary Tinkertoy structures, and here he was channeling the ghosts of rock concerts past to the National Mall.

“Richard wanted an event space for these conversations, for alternative programming,” says Diller. “An in-the-round structure made a lot of sense rather than a directional auditorium, because it doesn’t have a front and a back, so people engage more easily in a discussion. For us, the Mall is an inspiring spot, the symbolic place in the country for freedom of expression. But the buildings are fortresses, including the Hirshhorn, with its closed, defensive relationship to the Mall. We thought of it as inhaling the space of the Mall—and its democracy—into the hall. We wanted to create a building out of air. If you did the Bubble in New York, it would feel far less radical. The stately and sober institutions that line the Mall speak to a sense of authority, and this project plays into that, and in our mind invokes a more participatory democracy.”

“The strength of the Bubble is its spontaneity, and its respect for the original building,” says Gehry. “It’s like a separate work of art collaborating with the building. I like to see the feeling of spontaneity in architecture, achieving that sense of immediacy that you see in a Rembrandt that’s lasted hundreds of years. How do you get that in architecture? How do you do it with serious cultural buildings? I think they’re thinking closer to an artist, making an intervention in another architect’s work, like when Claes Oldenburg did a pair of binoculars in one of my buildings.”

***

Despite all the attention that the Bubble has received, little has been said about what might happen inside it. Koshalek’s idea is to create programming that will capitalize on the Hirshhorn’s location, to make the museum the nation’s cultural forum. “There are an estimated 400 think tanks, hundreds of embassies, scores of museums and research organizations, private and public, in Washington,” he says, “and here comes the first think tank that deals with arts and culture.”

Anticipating the program, Ann Hamilton, a large-scale multimedia artist who sits on the board, believes that it would be as important as the structure. “I do think the space is really brilliant, but the uniqueness of the architectural structure needs an equally unique curatorial program. Spaces can coax new kinds of thinking and create different experiences. But if it’s not met with an equally innovative curatorial program, the space alone can’t succeed. I’m looking forward to a conversation between a curator and the architects.”

To research the possible programming, Koshalek has recently attended the TED conference, the World Economic Forum, the Doha Climate Change Conference, an Aspen Institute art and design panel, and the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, among others, and wants to link the Hirshhorn to a larger world of ideas. “We will add more works to the collection and continue to stage one exhibition after another, but the museum has another responsibility, to engage the public with material that’s real and challenging,” he says. “Instead of following the established museum parade toward entertainment and blockbuster shows, the Hirshhorn is gearing toward research and dialogue complementing its exhibitions. Education has never distracted from an exhibition program.” The Smithsonian, the Hirshhorn’s parent organization, has pledged a ten-year grant of $4 million for operating the program, at $400,000 a year.

“The Bubble will become a center,” says the board’s acting chair, Constance Caplan. “It’s the center of the Hirshhorn, and it will serve the entire Smithsonian of which it’s a part, and lead to a greater [intramural] collaboration. The museums that are changing or responding to new needs are the ones that are going to grow. Dance, music, film, performance were not traditionally the purview of museums, but they are now. With this structure, the Hirshhorn will be able to look at what the arts mean in contemporary life and civic life.”

There are some, however, who are uncomfortable with the idea of a 21st- century art center. “The majority of the board support it, but of course there are those who are purists who think an art museum should just be an art museum,” says Schorr, the board treasurer. “But that’s not what museums are doing these days.”

The architects have designed the interior spaces for great flexibility to be reconfigured in different ways, with ring seating, couches and a movable stage. “We believe that space and atmosphere can affect the discussion,” says Diller. “A building like the Bubble is physically animate. It appears and disappears. Our tendency as architects is to control things, but here, it’s an open system, and has a dynamic effect on the people inside.”

“It’s immersive,” says Caplan. “You’ll have the feeling when you go in, that it’s different than any building you’ve been in before, that your horizons are going to change. You’ve got all these traditional buildings around, but here it’s going to speak to our interest in something different. There’s a sense of playfulness about it, excitement. You know that it will affect you, but not how.”

“The Bubble is a great way for the Hirshhorn to stay contemporary,” says Olga Hirshhorn. “I think that they’re proposing a serious and ambitious program, and I know it’ll work. It would be great for the museum and the whole Smithsonian. I’m looking forward to it. I’m very excited about it. I’m 92 going on 93, and I hope I live long enough to see it happen.”