The Mad Potter of Biloxi

George E. Ohr’s wild, wonderful pots gathered dust in a garage for half a century. Now architect Frank Gehry is designing a museum dedicated to the artist

Riding the train south through the deep pine woods of Mississippi in the early 1880s, tourists to the Gulf Coast came to Biloxi for sunshine and surf. Along with its beaches, the little town had its own opera house, white streets paved with crushed oyster shells, and fine seafood. Yet back in those years, there were no casinos as there are now, and not a lot to do besides swim, stroll and eat shrimp. Then, in the 1890s, the town boasted a new tourist attraction, one based on genius or madness, depending on one’s point of view.

Just a few blocks from shore, a five-story wooden “pagoda” labeled “BILOXI ARTPOTTERY” towered above the train tracks that ran across Delauney Street. Approaching it, a visitor saw hand-lettered signs. One read: “Get a Biloxi Souvenir, Before the Potter Dies, or Gets a Reputation.” Another proclaimed: “Unequaled unrivaled—undisputed— GREATEST ARTPOTTERON THE EARTH.” Stepping inside, a curious tourist found a studio overflowing with pots. But they were not your garden variety. These pots featured rims that had been crumpled like the edges of a burlap bag. Alongside them were pitchers that seemed deliberately twisted and vases warped as if melted in the kiln. And colors! In contrast to the boring beiges of Victorian ceramics, these works exploded with color—vivid reds juxtaposed with gunmetal grays; olive greens splattered across bright oranges; royal blues mottled on mustard yellows. The entire studio seemed like some mad potter’s hallucination, and standing in the middle of it all was the mad potter himself.

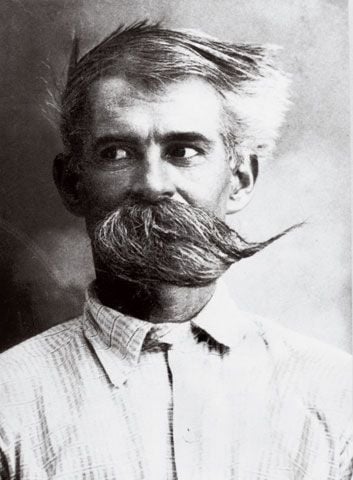

Viewed from a distance across his cluttered shop, George Ohr didn’t look mad. With his huge arms folded across his dirty apron, he looked more blacksmith than potter. But as they got a bit closer, customers could glimpse the 18-inch mustache he had wrapped around his cheeks and tied behind his head. And there was something in Ohr’s eyes—dark, piercing and wild—that suggested, at the very least, advanced eccentricity. If the pots and the man’s appearance did not prove lunacy, his prices did. He wanted $25—the equivalent of about $500 today—for a crumpled pot with wacky handles. “No two alike,” he boasted, but to most customers each looked as weird as the next. No wonder that as the new century began, thousands of the colorful, misshapen works collected dust on Ohr’s shelves, leaving the potter mad, indeed, at a world that failed to appreciate him. “I have a notion . . . that I am a mistake,” he said in an interview in 1901. Yet he predicted, “When I am gone, my work will be praised, honored, and cherished. It will come.”

Some 85 years after his death, the self-styled “Mad Potter of Biloxi” will be praised and honored as he predicted. Two years from now, Ohr’s startling ceramics will be showcased in a new $25 million Biloxi arts center designed by architect Frank O. Gehry, whose swirling silver Guggenheim Museum put Bilbao, Spain, on the cultural map. The Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art, a Smithsonian Affiliate, is named in honor of former Biloxi mayor Jeremiah O’Keefe and his late wife, Annette. Their family’s $1 million gift helped establish the museum, now housed in a small building downtown, in 1998. The new facility, scheduled to be completed in January 2006, will be nestled in a four-acre grove of live oaks overlooking the Gulf. As America’s first museum dedicated to a single potter, the complex will call attention to an art more often seen as craft. And if yet another story of “an artist ahead of his time” sounds clichéd, the resurgence of George Ohr will cap one of the art world’s most remarkable comebacks. For although his work is now in such museums as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, until the late 1970s, the only place to see an Ohr pot was in a garage behind a Biloxi auto shop—in a crate.

some are born eccentric, some achieve eccentricity and some, including certain rock stars and artists, have it thrust upon them. Evidence suggests that Ohr’s “madness” was a mix of all three. Born in Biloxi in 1857, he was the second of five children—“3 hens, 1 rooster and a duck,” he later wrote in a two-page autobiography published in a ceramics and glass journal in 1901.

Ohr considered himself the duck, a mischievous oddball who was, as he once put it, always in “hot aqua.” After elementary school, he spent a single season at a German school in New Orleans before dropping out in his early teens. He apprenticed as a file cutter, a tinker and as an assistant in his father’s blacksmith shop, then put out to sea. After one voyage, however, he decided that a sailor’s life was not for him. Finally, at 22, he chanced upon his life’s work when a friend invited him to New Orleans to learn to be a potter. “When I found the potter’s wheel I felt it all over like a wild duck in water,” he remembered. After learning how to “boss a little piece of clay into a gallon jug,” Ohr set out on his own to see what other potters were doing. In the early 1880s, he traveled through 16 states, dropping in on ceramics studios, shows and museums. By the time he got back to Biloxi in 1883, he had absorbed the essence of America’s burgeoning art-pottery movement. In Cincinnati’s Rookwood studio and a few others, potters were decorating their wares based on Japanese or French ceramics, adding animals, birds and bright floral designs. Ohr returned home determined to make art, not pots. But first he had to make a living.

While still staying with his parents, Ohr built a pottery shop next door to his father’s house, even crafting his own wheel and kiln, all for $26.80. Then he went looking for clay. Heading up the muddy TchoutacabouffaRiver, Ohr spent days digging the red clay along its banks, loading it onto a barge and floating it all back home. To this day, admirers suspect there was something in that clay that enabled Ohr to create wafer-thin pots with a delicacy no one else has ever equaled. Yet at first, there was nothing special about Ohr’s pottery. Working in his small shop, he supported his wife, Josephine, and their ten children by churning out chimney flues, planters and ordinary pitchers. He amused some customers with pots in anatomical shapes and clay coins imprinted with lewd picture puzzles. In his spare time, he experimented with pieces he called his “mud babies.” Brooding over them, he wrote, “with the same tenderness a mortal child awakens in its parents,” he created fantastic shapes glazed with wild colors. When he took his mud babies to exhibitions in New Orleans and Chicago, they sold poorly. Back home in Biloxi, his humorous signs promoting his “Pot-Ohr-E” gave Ohr a reputation as an eccentric whose shop was worth a visit mainly for a laugh.

Potters say that fire adds devilish details to their work. No matter how carefully one throws a piece of ceramics, a kiln’s inferno causes chemical glazes to erupt in surprising colors. For Ohr, fire was a further catalyst for his creativity. At 2 a.m. on October 12, 1894, an alarm was sounded; Biloxi’s Bijou Oyster Saloon had caught fire. The blaze spread quickly through downtown. It raged through the Opera House, several cottages belonging to Ohr’s father and the grocery run by Ohr’s mother. Finally, it gutted the Pot-Ohr-E. Later that day, Ohr picked through the ashes to dig out the charred remains of his “killed babies.” He kept most of them for the rest of his life. When asked why, he replied, “Did you ever hear of a mother so inhuman that she would cast off her deformed child?” Aloan enabled him to rebuild his shop, adding its telltale “pagoda,” and like a glaze that turns an astonishing magenta when fired, Ohr emerged from the tragedy determined to make pottery as distinctive as he was. “I am the apostle of individuality,” he once said, “the brother of the human race, but I must be myself and I want every vase of mine to be itself.”

in both museum and private collections, nearly every Ohr pot is dated to the same short period: 1895-1905. During this decade, Ohr labored at a feverish pace, turning out thousands of amazing, outrageous, wonderful pots. Just as Cézanne was breaking up the plane of the painter’s canvas, Ohr was shattering the conventions of ceramics. He made pitchers whose open tops resembled yawning mouths. He threw slim, multitiered vases with serpentine handles. He lovingly shaped bowls into symmetrical forms, then crumpled them as if to thumb his nose at the art world. He fired his works into kaleidoscopic colors that only a few years later would be called fauve—for the “wild” hues of Matisse and other Fauvists. And almost a decade before the Cubists added print to their canvases, Ohr scrawled on his ceramics with a pin. On an umbrella stand he created for the Smithsonian circa 1900, Ohr etched a rambling letter, adding an equally rambling salutation that concluded: “Mary had a little lamb / Pot-Ohr-E-George has (HAD) a / little POTTERY ‘Now’ where is the Boy / that stood in the Burning Deck. / ‘This Pot is here,’ and I am the / Potter Who was / G. E Ohr.”

Ohr also stepped up his self-promotion. Crafting his own image, he billed himself as Biloxi’s “Ohrmer Khayam,” and George Ohr, M.D. (The M.D., he explained, stood for “Mud Dauber.”) Signs he took with him to exhibitions and fairs unabashedly proclaimed “ ‘GREATEST’ ARTPOTTERON EARTH, ‘YOU’ PROVE THE CONTRARY.” As unconventional in private as in public, Ohr papered the parlor of his home in gaudy patchwork patterns. He had married 17-year-old Josephine Gehring, a blue-eyed New Orleans belle, in 1886, when he was 29. He and his “darling Josie” named their first two children Ella and Asa. Both died in infancy. Then, noting that his own initials—G.E.O.—were the first three letters of his name, Ohr saddled his next eight kids with the same gimmick, naming them Leo, Clo, Lio, Oto, Flo, Zio, Ojo and Geo. He often was up late playing with rhymes, and in a local photography studio, he twisted his mustache and face to produce some of the wackiest portraits ever taken.

Locals were not amused, and many considered their native mud dauber certifiably insane. More likely, Ohr was just ahead of his time, in promoting his work as well as crafting it. Decades before Salvador Dali began his self-aggrandizing antics, Ohr asked a reporter, “You think I am crazy don’t you?” Assuming a sober demeanor, the “mad” potter confided, “I found out a long time ago that it paid me to act this way.” It did not pay well, however. Ohr was a notoriously bad businessman. He put shockingly high prices on his favorite pots because he simply could not bear to part with them. On those rare occasions when customers paid the asking price, Ohr would chase them down Delauney Street, trying to talk them out of the purchase. Ohr didn’t seem to care that he made so little money. “Every genius is in debt,” he said.

By the turn of the century, Ohr had begun to get a little respect if not much success. Asurvey of ceramics published in 1901 called his body of work “in some respects, one of the most interesting in the United States.” Although Ohr exhibited his pots around the country and in Paris, the prizes always went to more traditional pottery. Ohr’s only medal, a silver for general work, came at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Centennial Exhibition in St. Louis. Still, he did not sell a single piece there. Even his few admirers misunderstood him.

Some critics said Ohr’s “deliberately distorted” works displayed an utter lack “of good proportion, of grace, and of dignity.” When praise did come, it was more for his colors (which Ohr considered an accident enhanced by fire) than for his shapes. “Colors and Quality—counts nothing in my creations,” he fumed. “God, put no color or quality in souls.” Determined to demonstrate his forte, he began making unglazed pots with even stranger contours.

Looking to the future for acceptance, Ohr announced he would no longer sell his works piece by piece but would “dispose of the whole collection to one creature or one country.” If few collectors were interested in Ohr’s single pots, however, no one was interested in thousands of them, making him only more angry and determined. When a New Orleans museum accepted a mere dozen of the 50 unsolicited pieces he’d sent them, he told the curator to “send it all back immediately.” Once, in a fit of despair, he gathered a shovel, lantern and bag of pots, then hiked deep into the woods to bury his treasure like a pirate. If he left a map, it was probably burned by his son Leo, who, one evening after Ohr’s death, torched all of his father’s papers, including the secret recipes to his lovely glazes. Ohr’s buried treasure is believed to be still in the Back Bay section of town—somewhere.

In 1909, claiming he hadn’t sold one of his mud babies in more than 25 years, Ohr closed his shop. Though just 52, he never threw another pot. Having inherited a comfortable sum when his parents died, he devoted the rest of his life to enhancing his reputation as a loon. He let his beard grow long, and donning a flowing robe for Biloxi’s Mardi Gras, he roamed the streets as Father Time. In his final years, he could be seen racing a motorcycle on the beach, white hair and beard flying. He often spoke and wrote in a disjointed stream of consciousness: “We are living in an Age of Wheels—more wheels, and wheels within Wheels—And MACHINE ART Works—is A fake and Fraud of the deepest die.” Still confident that the time would come when his work would be recognized, Ohr died of throat cancer at age 60 in 1918. His pottery, some 7,000 pieces in crates, remained in the garage of his sons’ auto-repair shop. Every now and then, a few kids carrying BB guns would sneak in and take some pots out for target practice.

Ahalf-century after Ohr’s death, James Carpenter, an antiques dealer from New Jersey, was making his annual winter tour of the GulfCoast. Carpenter wasn’t looking for pottery; he was shopping for old car parts. One sweltering afternoon in 1968, he stopped at the Ohr Boys Auto Repair in Biloxi. While he was browsing, Ojo Ohr, then himself in his 60s, approached Carpenter’s wife. In his slow Mississippi drawl, Ojo asked, “Would y’all like to see some of my daddy’s pottery?” Carpenter rolled his eyes as if to suggest they had to be going, but his wife, whose curiosity was apparently aroused, said, “Sure.” Back at the cinder block garage, Ojo opened the doors to reveal the most amazing collection of pottery in the history of American ceramics. Several pieces were set out on tables; the rest filled crates stacked to the 12-foot ceiling. A few had been cleaned of their greasy film. Catching the sunlight, they sparkled like the day Ohr had given them life.

Carpenter had never heard of Ohr. Few outside Biloxi had. Yet he recognized the beauty of the work, as did Ohr’s son. When Carpenter reached to pick up a pot, “Ojo chewed me all out,” he later recalled. “ ‘Nobody touches Daddy’s pottery!’ Ojo said.” But he relented, and Carpenter, wondering if he might be able to sell them, was allowed to examine a few pots as Ojo held them up for inspection. Finally, Carpenter decided to take a gamble. He offered $15,000—about two bucks a pot—for the entire lot. Ojo left to consult with his brother and came back shaking his head no. It took several more years for the brothers to decide to part with their legacy and agree on an asking price. In the end they settled on a sum that back then, says Carpenter, “would have bought a very desirable house”—in the range of $50,000. But according to one Ohr scholar, by the time Carpenter returned with the money, Ojo had upped the price to $1.5 million. After three more summers of negotiations, for a price rumored to be closer to the lower figure, Carpenter moved Ohr’s treasures to New Jersey, where they began trickling onto the marketplace.

Meanwhile, the art world had begun catching up to Ohr. During the 1950s, a school of Abstract Expressionist ceramics had flowered, creating free-form works that looked more like sculpture than pottery. Artists, including Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol, bought Ohr’s pots, as did several collectors, though the curator of ceramics at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History protested Ohr’s inclusion in a show in 1978, calling him “just plain hokey.” Only in 1984, when Ohr pots appeared in paintings by Johns at New York’s Leo Castelli Gallery, did praise and critical esteem begin to flow. After a series of one-man shows of Ohr’s work, collectors such as Steven Spielberg and Jack Nicholson purchased pieces and drove prices up. Today, the same pots scorned a century ago sell from $20,000 to $60,000 each. Back in 1900, when his pots were barely selling at all, exasperated exhibition organizers would ask Ohr to put a value on his works. “Worth their weight in gold,” he would answer. In retrospect, he sold himself short.

Today, Ohr is hailed as a “clay prophet” and “the Picasso of art pottery.” His resurrection proves that madness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. But then, he always knew that, and so did visitors to his shop, at least those who were trained in the classics and paid strictest attention. On their way out of the cluttered, crowded studio, they would pass yet another hand-lettered sign, this one inscribed with a Latin phrase: Magnus opus, nulli secundus / optimus cognito, ergo sum! Translated it read: “Amasterpiece, second to none, The best; Therefore, I am!”