The Deerstalker: Where Sherlock Holmes’ Popular Image Came From

The literary detective’s hunting cap and cape came not so much from the books’ author as from their illustrators

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120726085011writingset.jpg)

![]() Glen S. Miranker, a.k.a. A Singular Introspector, a.k.a, The Origin of Tree Worship, has one of the largest collections of Sherlock Holmes books, art, and ephemera in the United States. Fortuitously yesterday, while researching the illustrations of the Holmes canon, I discovered that part of Miranker’s collection is currently on view at the Book Club of California in San Francisco. I rushed right over.

Glen S. Miranker, a.k.a. A Singular Introspector, a.k.a, The Origin of Tree Worship, has one of the largest collections of Sherlock Holmes books, art, and ephemera in the United States. Fortuitously yesterday, while researching the illustrations of the Holmes canon, I discovered that part of Miranker’s collection is currently on view at the Book Club of California in San Francisco. I rushed right over.

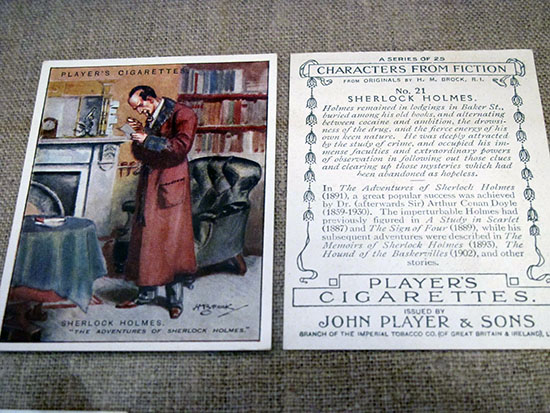

As part of our series on Sherlock Holmes, I had been reading up on the visual depictions of Holmes and the extent to which the handful of artists who illustrated Arthur Conan Doyle’s texts over the years—namely Sidney Paget, Frederic Dorr Steele, and H.M. Brock—actually (arguably) did more to define our idea of the quintessential detective than the author himself.

Original Sidney Paget drawing from 1901 for The Hound of the Baskervilles, published in The Strand Magazine.

Sherlock’s unmistakeable deerstalker hat, for example, was never mentioned in the printed words of the Holmes books. When Sidney Paget illustrated Doyle’s story, The Boscombe Valley Mystery, for publication in The Strand Magazine in 1891, he gave Sherlock a deerstalker hat and an Inverness cape, and the look was forevermore a must for distinguished detectives—so much so that while the deerstalker was originally meant to be worn by hunters (hence the name), the hat now connotes detective work, even without a detective’s head inside it.

One of several editions of The Strand Magazine in which Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles was serialized. The American editions featured color images on the cover, while the UK editions were blue and white.

Of course, as many Sherlockians know, the deerstalker wouldn’t have been Holmes’s daily choice of headwear. These hats were country gear, not fit for the city. But several of Doyle’s most popular stories were set outside of town, including The Hound of the Baskervilles, which happens to be the primary focus of Glen S. Miranker’s collection.

Inside the Book Club of California, which sits on the fifth floor of an easily missed building in downtown San Francisco, Miranker’s objects fill three glass cases and cover one long wall. There is antiquarian edition after promotional advertisement celebrating the genius of Doyle’s third novel. Miranker even possesses a couple of leaves from the original manuscript, which, the exhibition text explains, are incredibly rare:

Most of the Hound manuscript was distributed as single pages in a promotion to bookshops for public display by its American publisher, McClure, Phillips…After the exhibition, most of the pages were thrown away. As a consequence of this rude treatment, there is only one known chapter intact (in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library) and perhaps fewer than three dozen single pages.

An original ink, pencil and crayon illustration by Frederic Dorr Steele, used on the cover of Collier’s Magazine in 1903 and later on the poster that closed out actor William Gillette’s tenure as Sherlock in the theater. The image features Holmes in a smoking jacket, examining a bloody handprint.

Needless to say, Miranker claims to have purchased items for his collection that cost more than his first home. One suspects that later homes have rebalanced that equation, as Miranker was for a time the Chief Technology Officer at Apple, among other tech executive jobs. Today, Miranker collects not only Sherlockian items, but also items related to cryptologic history and radio.

Poster for the 1959 horror version of The Hound of the Baskervilles

Because many of the objects in Miranker’s collection feature art and illustration, it’s easy to see how the Sherlock stories became like celebrity glue, making wildly famous any person or product that became associated with the fictional detective. Commercial art on cigar boxes, cigarette papers and playing cards featured not only Sherlock himself, but also actors who had played him in the theater, and all the set and costume pieces that distinguished his persona. These drawings were done by a variety of artists over the years, and their overall styles reflected the graphic zeitgeist of the time (30s Hollywood, 50s noir), but all were influenced by the earliest drawings, which endowed Sherlock with his signature accessories.

Considered a desirable collector’s item, illustrated cigarette cards were used to uphold the structure of the packaging starting in 1875. This one shows an image drawn by H.M. Brock.

If you find yourself in the Bay Area and you have a penchant for literary history (Sherlockian or otherwise), it’s worth a few minutes of your time to drop by the Book Club of California to see what’s on display.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)